Content warning: This blog post references homophobic attitudes and the historic policing of LGBTQ+ lives.

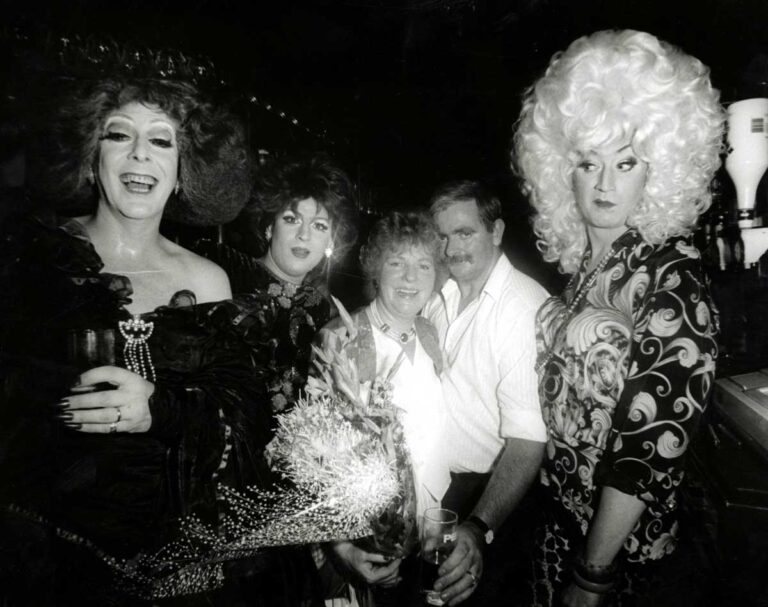

In January 1987 the iconic LGBTQ+ bar and drag venue, the Royal Vauxhall Tavern (RVT), was raided by police. The AIDS pandemic was at its height. The RVT was a haven in the midst of this, a space for jovial escapism, as well as political organising and many charity events. At the raid, police officers – strikingly – donned rubber gloves.

Lily Savage was onstage for a residency at the time, and notoriously quipped: ‘Well, well, looks like we have help with the washing up.’ (See footnote 1.)

The raid was perceived as heavy handed and illustrative of the wider over-policing of the gay community at the time. Despite the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, distinct methods of policing the LGBTQ+ community, particularly men, continued (see footnote 2). The 1970s saw a shift in political consciousness towards pride and equal rights, rather than just a desire for tolerance; in the UK it was the decade of the first Gay Pride parade, the formation of Gay’s the Word bookshop, and the creation of Gay News, Britain’s first gay newspaper. But as this case shows, there was also a backlash to these growing freedoms and visibility.

Amyl nitrite: poppers

The raid had been prompted, in part, by a growing concern about the use of amyl nitrite, more commonly known as ‘poppers’, a liquid chemical that was sniffed (see footnote 3). Amyl nitrite was originally used for heart conditions, but over time the use changed. These drugs were, and still are, associated with the gay community, partly due to their use in relaxing the body and as a sexual stimulant.

In December 1986, the Sunday Telegraph ran a story under the sensationalist headline ‘Poppers, the new danger drug in the pub, as easy to buy as crisps’. The article named the RVT as a venue where poppers could be readily purchased.

Poppers were not, and are not, illegal, although in 1986 the government informed Parliament that they were considering their criminalisation (see footnote 4). Home Office records from the time show that they thought that the article was misleading and that there was no intention to control poppers under the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971) or the Poisons Act (1972).

Most problematically, the article linked the use of poppers (common in the gay community) to the spreading of AIDS (also prominent in the gay community), stating it could make ‘users more vulnerable to the killer AIDS virus’ (see footnote 5). As author Adam Zmith notes, this assertion had actually already been debunked at the time.

December 1986

Shortly after this article, the RVT was raided. On 17 December 1986, 22 bottles of poppers were found and seized as a ‘noxious substance’, a tenuous charge. Brenda McConnon, the landlady, and several staff members were arrested (see footnote 6). There had been no prior discussion with the licensee over drugs, unlike with other publicans. Police admitted that their interest in the RVT’s selling of poppers came from the initial Sunday Telegraph article. In the aftermath, many other pubs stopped selling poppers, worried of the implications of this raid.

January 1987

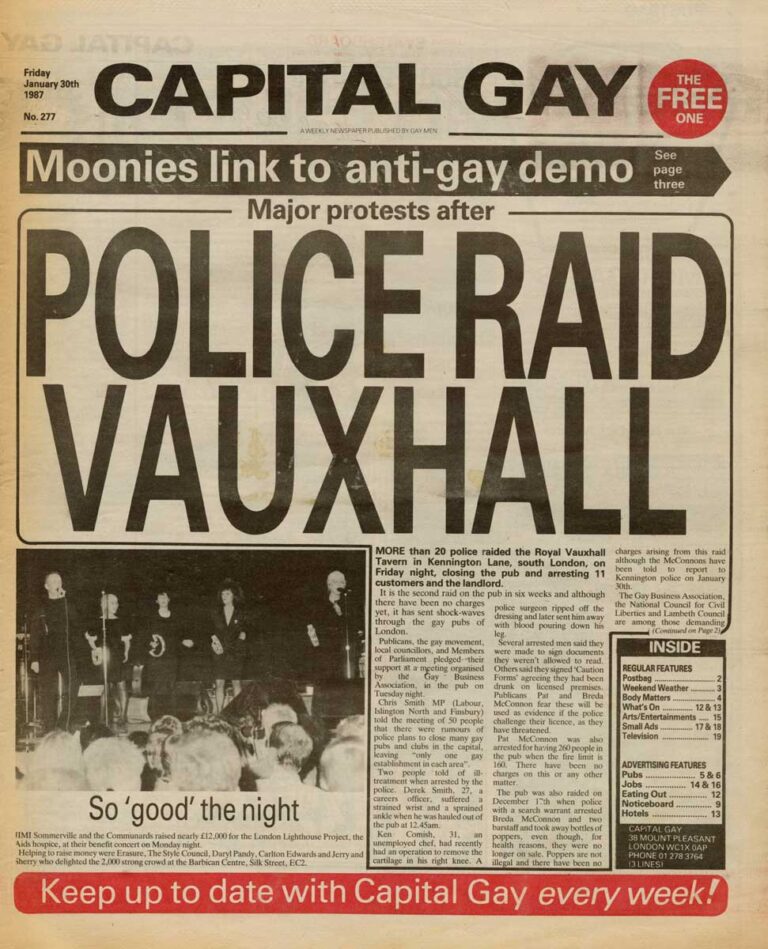

On 24 January 1987 the infamous ‘gloves raid’ occurred. 35 officers swarmed the RVT. This longstanding venue, which was central to London’s queer scene, was described in one police document as ‘frequented by homosexuals, drug addicts and some members of the criminal fraternity’. The document outlined the intention of the police to try and strip the venue of its late-night licence by gathering evidence of drunkenness on the premises, ‘lewd conduct’ or going over-capacity for the licence (see footnote 7). Ultimately 11 arrests were made for drunkenness, and two punters were reported injured. The raid made the front page of the Capital Gay newspaper.

This blog is largely based on the archive file HO 287/4374, which mainly covers this second raid (see footnote 8). Press interests, public complaints and Parliamentary Questions seem to have triggered the surviving correspondence. Our records unearth tensions between the Metropolitan Police and Home Office. In its aftermath the Home Office sought more information about why the raid had taken place.

A key focus was scientific research into amyl nitrite, showing many differing opinions on the harmfulness of poppers and significant discussion about their legal position. Advice on the use of poppers was sought from various bodies, including the Crown Prosecution Service in May 1987, who commented, ‘In the present climate I doubt whether it is in the public interest to have widely available unrestricted supplies of a drug whose sole purpose is the facilitation of anal intercourse’. A Home Office official responded, ‘it is not as far as I am aware, part of the government’s response to the AIDS disease to use criminal justice sanctions in order to control sexual activities which may be conducive to its spread’.

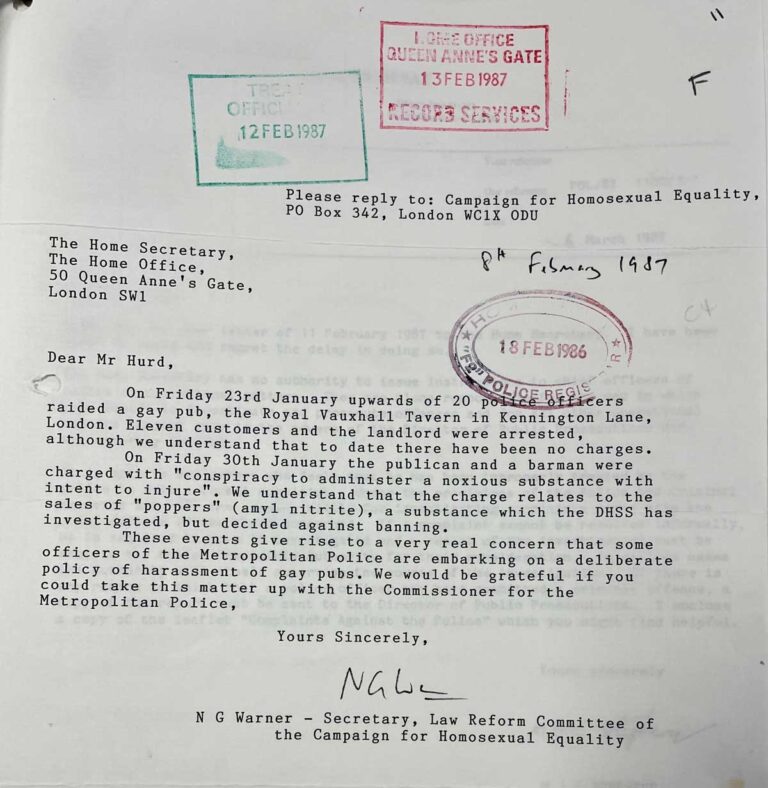

Parliamentary and public scrutiny

The raid prompted a backlash from various community groups and other venues. The proprietor of the Kings Arms in Soho, another gay pub, wrote to the Home Office to complain about the use of taxpayers’ money on such raids: ‘It would appear “Irregularities” could have been investigated by substantially less manpower at a more acceptable hour and in the correct manner’. The secretary of the Law Reform Committee of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality expressed ‘a very real concern’ that such raids demonstrated ‘a deliberate policy of harassment of gay pubs’ and urged the Home Secretary to investigate. Various advisory committees submitted their opinions and assistance was sought from Galop, the Gay London Police Monitoring Group.

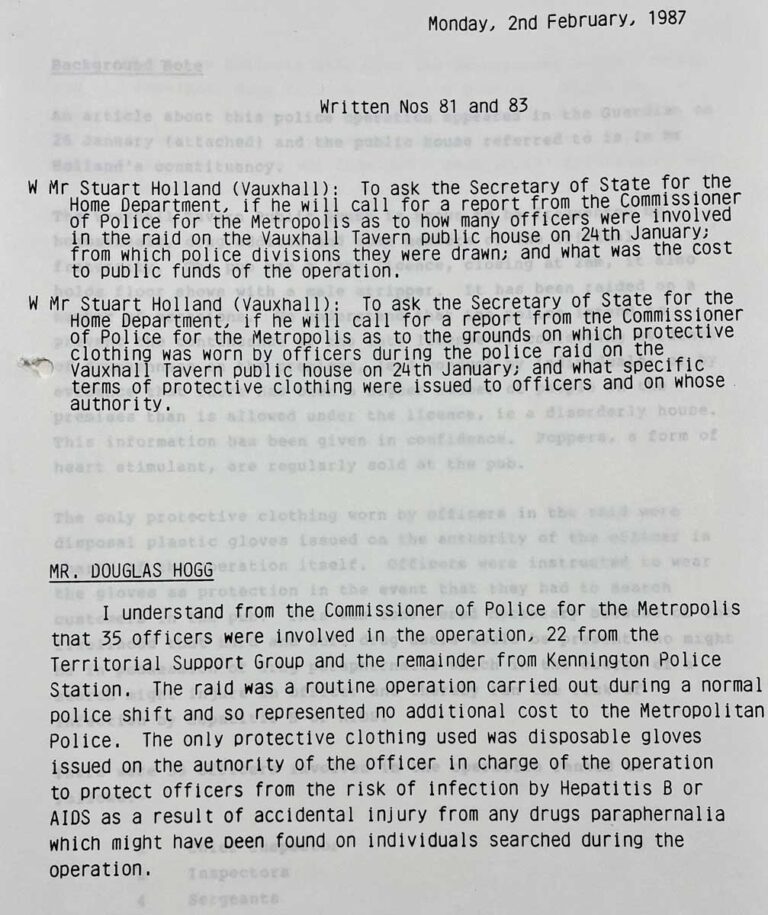

Parliamentary questions similarly focused on the number of police involved in the raid, the use of gloves and evidence of local objections. No complaints concerning alleged drunkenness at the RVT had been received from residents in the Vauxhall constituency (historically it was often such complaints that prompted raids, but this was not the case here). If this was such a concern, it seems odd that the RVT’s license was renewed in early February 1987 at Camberwell Magistrates Court with no objections from the police.

In Parliament it was argued that this was a routine operation and no additional costs were incurred, despite the use of 35 officers of various ranks. Concerns were raised about the prioritising of this raid over other police matters, such as robbery, which was considered of high importance in the area.

Gloves controversy

The use of gloves in particular was controversial, being seen as representing a dehumanising attitude towards gay people, at a time when the community was going through its own significant trauma with the AIDS pandemic.

The police defended their use of gloves, saying that they believed they might have had to search individuals for drugs or encounter ‘drug paraphernalia’ (presumably needles). However there had never been any suggestion that the RVT was popular with intravenous drug users. This lack of understanding, or possibly wilful ignorance, seems surprising given the government’s extensive AIDS education campaigns in this era, including leaflets sent to every household in the country. Letters from Councillors Graham Nicholas and Helen Dawson, co-chairs of the Association of London Authorities Lesbian and Gay Committee, asked if gloves were similarly used in other drug raids.

What our files show is the that the charges themselves were fundamentally disputed. When the case finally went to court several years later, after a long, fraught wait, it was dismissed.

Community resilience

This raid served to alienate the queer community at an already difficult time, reinforcing popular prejudices. The following year Section 28 was introduced, prohibiting the ‘promotion of homosexuality’, such was the contentious political climate around LGBTQ+ lives. However, the community was resilient and used to fighting back.

The records of the RVT raid show an interesting shift in tone from the earlier queer raids in our collection, dating from the period in which homosexual acts were criminalised. While these earlier records often show acts of defiance, there is not the same community backlash, understandably, in later cases such as this. It is heartening to see such targeting and raids were no longer widely accepted by politicians, community groups, and by LGBTQ+ people themselves.

The RVT continues to be a fun, lively venue, but also a sanctuary for the LGBTQ+ community. In 2015, the RVT was made a Grade II listed building; the UK’s first building to be listed in recognition of its importance to LGBTQ+ community history.

Many thanks to Bishopsgate Institute for all their research support on this blog.

Footnotes

- This has become a key part of the re-telling of the raid, that is regularly quoted but its actual occurrence remains unclear.

- Records show that arrests relating to sex acts between men actually increased after the passing of the Sexual Offences Act (1967).

- For a comprehensive history of poppers, see Adam Zmith, Deep Sniff: A History of Poppers and Queer Futures, 2021.

- ‘Amyl Nitrite’ Volume 107: debated on Friday 19 December 1986. Hansard (Parliamentary debates). Such debates sporadically continue. In 2016, Conservative MP Crispin Blunt spoke openly in Parliament about his use of poppers and the effect criminalising them would have on the gay community.

- Sunday Telegraph, December 1986, copy included in HO 287/4374, The National Archives.

- Breda McConnon remembers some of the Police raids on the RVT – YouTube

- At a public meeting at the RVT following the raid, openly gay Labour MP Chris Smith spoke of rumours that the Police wanted only one gay pub in each division. GALOP annual report, 1986-87.

- The series HO 287 relates to Home Office functions and responsibilities in the field of police matters.

Interesting and informative blog – thanks for posting!

Gosh!

I remember these raids so well. I was never a ‘regular’ at the RVT, although I was a huge fan of Lily Savage and did pay quite a few visits to Vauxhall around this time.

There were so many of these abusive raids around gay venues at this time. Capital Gay was a real eye-opener, each week (seemingly) with a new story of police abuse. I was a very naive 25 year-old in 1987 and just couldn’t understand why my life was so at odds with the ‘mainstream’.

These raids in conjunction with the use of Pretty Policeman (Agents Provocateurs who entrapped gay men in cottages (public toilets), and the whole Section 28 debacle), were all part of Thatcher’s attacks on gay men. Her completely out-of-date hatred was partially her response to the AIDS crisis and partially her delusional belief that we all needed to return to Victorian values.

The gay community (long before we became LGBTQ+), were a soft target in the same way that refugees are ruthlessly attacked by today’s government. However, the gays, (in the 1980’s) were in the mood to be “bolshy” and were not going to lie down and return to the pre 1967 closet. Pride became stronger and had a more radical feel to it. There were a number of high-profile events to raise money for defence funds and to bring these matters to the attention of the wider community.

Eventually the raids on bars eased, although the Pretty Police entrapment continued for another few years.

These policies damaged the relationship between gay men, the police and the government for many years . To this day I still do not understand why any person would vote for a Tory government which so ruthlessly attacks its own citizens (and continues to do so with “Austerity” and other ideological ruses.)

28/03/23, RIP Paul O’Grady/Lily Savage. One of the finest ‘turns’ in the business! I suspect the Met found out quite quickly why it’s never a good idea to try and upstage a drag queen.

It is illuminating to note the date stamps on the letter to Hurd. Apparently the Police department’s keen attention to detail overlooked updating the year…