To celebrate National Storytelling Week 2021 I want to dive into the world of biomolecular material analysis and showcase how science can aid in the understanding of medieval manuscripts.

Manuscripts hold stories. Most of the time when we study these objects, we concentrate on what’s written on the page – but what if the materials used to create the manuscript could also tell stories?

Thanks to recent advances in DNA sequencing, we are able to study manuscripts on a molecular level – a field known as biocodicology. Scientists can use DNA, microbial and protein analysis to enrich understanding of these objects and the people who used them.

Biocodicology can give us insight into the methods used to construct the book and identify the species and sex of the animal used to make leather or parchment. It can tell us where a book was made and even offers a glimpse into historic wildlife management and pastoral farming practices. In an archive, we can find this information hidden in leather, parchment, glues, and even mould.

A fascinating example of this technique being used is the analysis of The Gospels of St Luke, an exceptionally well-preserved manuscript from the 12th century, now held at York Minster Cathedral. When examining the leather cover researchers from BioArCh, University of York, discovered tiny 1.3 mm holes created by a furniture beetle (Anobium punctatum). These beetles live in Northern Europe, confirming where the book was likely made. Protein analysis showed that the leather cover was made from roe deer and the parchment pages are made from a mixture of sheep, calf and goat. Previously, scholars had thought that the pages were only made from calf.

One of the most intriguing findings was that 20% of the DNA found in the book came from humans. It was especially prominent on pages containing oaths, which would have been frequently kissed and touched by medieval readers. The researchers also found two microbes that are closely linked to humans: propionibacterium, which causes acne and staphylococcus, which is responsible for many strains of staph infections.

The National Archives Collection Care department has had biocodicology on the radar for quite some time. We first contributed to BioArCh projects in 2015. Since then, the field has continued to grow and in 2019 conservator Holly Smith attended an international biocodicology workshop in Washington, D.C. The workshop brought together expert historians, conservators, and scientists to share ideas, challenges and foster new collaboration opportunities.

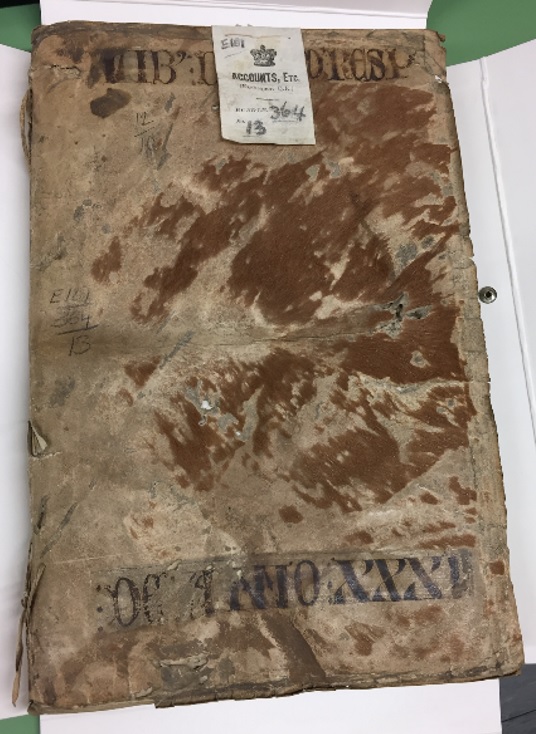

Holly is now applying what she has learnt to The National Archives’ vast Limp Vellum Binding collection, containing over 1,300 books from 1284 to 1820. She is conducting an in-depth study of their condition and materials to find out what they can tell us about the evolution of the limp vellum structure over the 600-year period, the changing quality and patterns of parchment use, and how this information ties in to the socio-economic conditions of the time in which they were created. By understanding the methods used, and contexts in which they were created, we can join the dots on what they tell us about our own history.

As the field of DNA analysis on medieval manuscripts has grown it has expanded to other historic materials. Over the next three years, we are involved in an innovative project to use wax as a bimolecular archive, called ArcHives. The project is led by an international team of scientists and historians who aim to: inform understanding of the geographic origin of beeswax (and bees); better understand the changing diversity of the hive microbiome in modern and historical beeswax; and uncover DNA of individuals associated with the production of the legal documents trapped in kneaded wax.

The National Archives holds over 250,000 wax seals dating from the 11th to the 20th century. This project will allow us to gain knowledge around the material composition of wax seals in our collection, allowing for a deeper understanding of the physical and chemical processes responsible for their ageing and degradation.

You can learn more about this work on the project website.