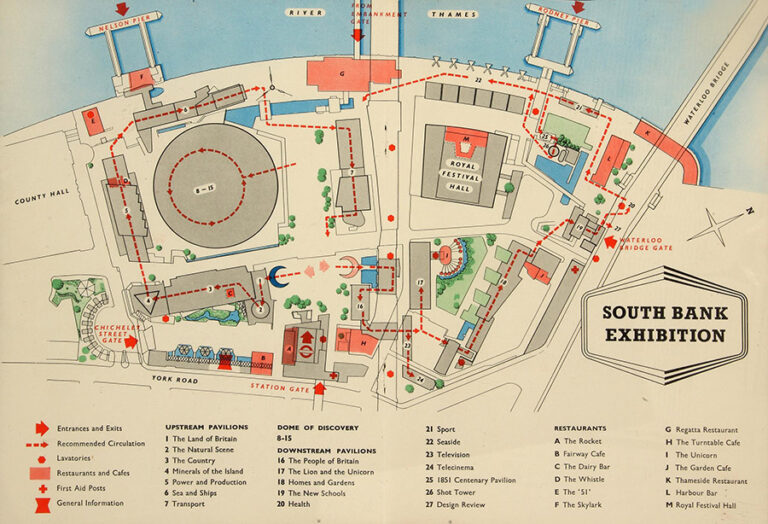

If you had taken a walk along the south bank of London’s River Thames 70 years ago, you would have encountered a spectacular scene. Hundreds of people swarming around futuristic-looking walkways, looking up in awe at the enormous Dome of Discovery and the miraculous Skylon, enjoying alfresco dining and scurrying in and out of various unique and beautiful pavilions. The Festival of Britain was in town.

70 years on, just a few remnants of the Festival still remain across the country, most notably perhaps the Royal Festival Hall. However the legacy of the Festival of Britain on art and design, urban planning, and cultural memory is still very strong. At The National Archives, we want to celebrate this unique cultural moment by showcasing the records we hold from the Festival of Britain Office and by drawing on the memories of those with direct connections to the Festival and its legacy.

During my research for this article, I spoke to Ray Leigh, who worked as a designer on the Festival of Britain, and Henrietta Goodden, designer and academic and daughter of Festival architect, Robert Goodden. I am very grateful to both of them for sharing their memories and thoughts about the Festival, which form the basis of this blog.

‘A Tonic to the Nation’

The Festival of Britain was first conceived as an event to mark the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition. However, instead of an international exhibition, it was to be an opportunity to celebrate British achievements in the arts, architecture, science, technology and industrial design.

It was being organised at a time when Britain was still suffering from the physical and psychological effects of the Second World War. Its towns and cities were still in ruins from the aerial bombing of the Second World War, and with continued economic hardship, spirits were generally low. The prospect of a national festival was seen by many as a welcome relief from their troubles and a sign of optimism for the future.

London was a very drab grey city at that time. There was a huge amount of damage as even the Festival site had been bomb damaged. So for a 19-year old, it was all a hope for the future!

Ray Leigh

The organisers wanted to use the Festival to showcase the work of British architects, designers and artists, whose career opportunities during the war had been quite limited. This was their chance to show to the world an optimistic, forward-thinking vision of Britain’s future.

The Festival was officially opened on 3 May 1951 with 22 freestanding pavilions on the Southbank site, themed around ‘The Land’ and ‘The People’. The site attracted 8.2 million visitors over the summer of 1951[ref]Harriet Atkinson, The Festival of Britain: A Land and its People, (2012), p. 156.[/ref].

The Lion and the Unicorn

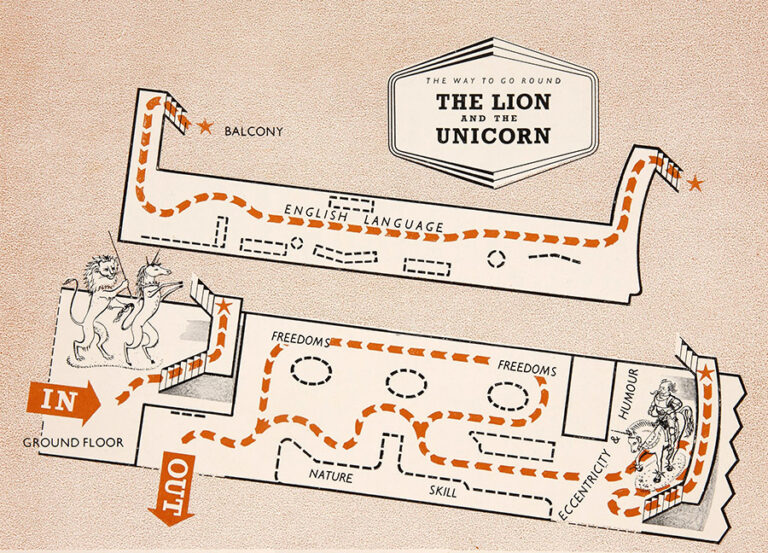

If you were to continue your tour of the Festival site, you would be spoiled for choice in terms of the activities and attractions on offer. After visiting the People of Britain display and enjoying a spot of tea at the Turntable Café, you would encounter another striking structure. The glittering plate-glass front of this rectangular building rose 45 feet up to a curved oak-beamed roof, allowing glimpses through to an airy spacious interior. This was the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion: a picture of modern simplicity.

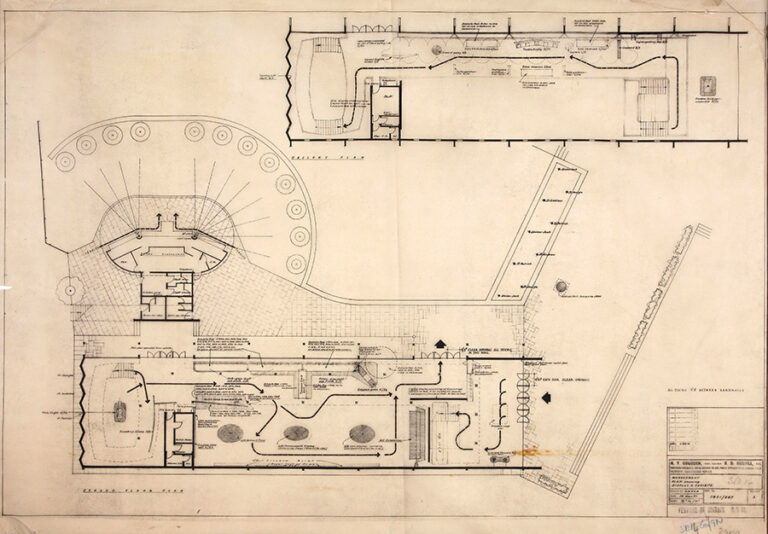

The Pavilion was designed by R D ‘Dick’ Russell and Robert Goodden, who had both recently been appointed professors at the Royal College of Art when they were given this new commission by Director of Architecture, Hugh Casson[ref]Henrietta Goodden, The Lion and the Unicorn, (2011), p. 75.[/ref]. The pavilion was intended to display ‘British character and tradition’, a theme which the designers approached with a sense of humour and joy.

There was a light-heartedness about it which I think is the thing that comes through really. It was all about airiness and being uplifting; about colour and space. Everything was very bleak after the war and the whole of the Southbank was all about lifting the national character. But I think in the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion, partly because of its enormous size, with no upper floor, I think that must have come through quite strongly.

Henrietta Goodden

Designers and students

One principle which the designers held to be very important was that they should be allowed to manage the design of the entire pavilion, the interior displays as well as the structure. They also had a great respect for traditional methods of design and construction, a philosophy born out of the Arts and Crafts movement which fitted beautifully with the theme of the pavilion. The work on the pavilion was very collaborative and students were encouraged to be involved in the process[ref]Ibid., pp. 130-1.[/ref].

One student who got involved was Ray Leigh. Having left the Army in 1949 and recommencing his studies at the Architectural Association, he wrote to Dick Russell to ask for a job.

As he was professor at the Royal College of Art, I thought there’ll be students there lining up to try and get holiday jobs, which is what I was applying for in his office. Somewhat to my surprise I got a call from him, saying ‘yes, come along and have a chat to us and we’ll see what we can do’. I was in awe of the man. Here was I, a fresher, in a world where people like him had already established distinguished careers. But to my surprise I got a call about a week or so later saying ‘yes, come and start in the summer holidays and work with us on the Festival of Britain!’

Ray Leigh

Entering the pavilion

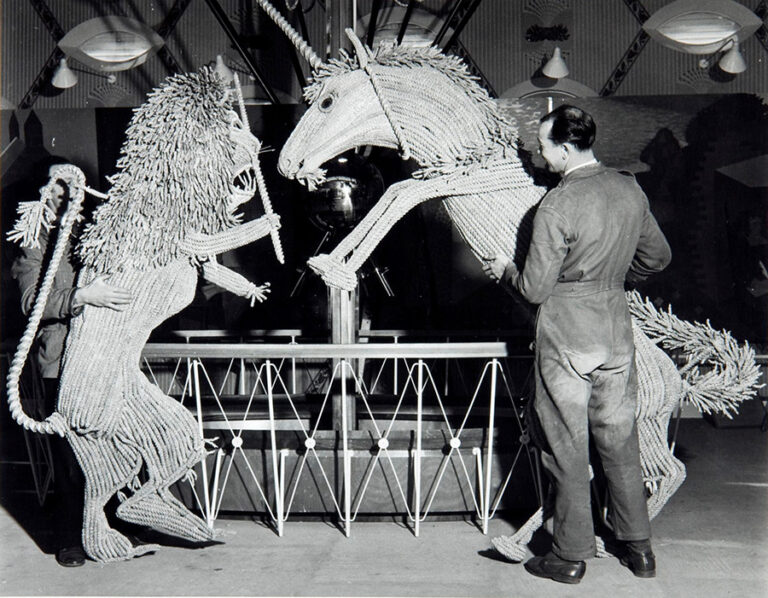

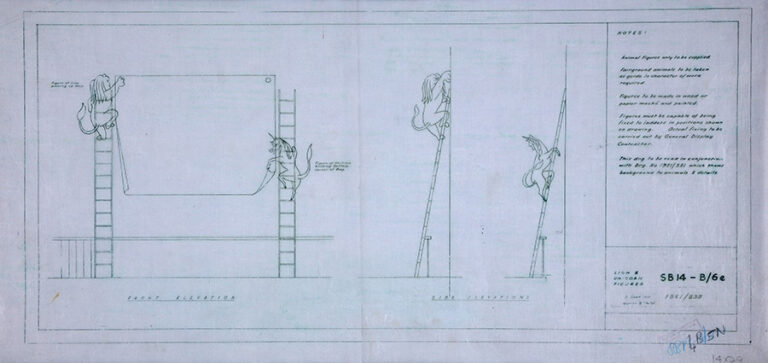

All of the pavilions at the Festival of Britain were designed to lead the visitor through a story through the theme they were exploring. As you entered the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion, you would first be struck by the huge straw models of the lion and the unicorn set on the wall to your left. These were made by Fred Mizen, an agricultural worker and expert in straw work, to demonstrate a traditional British craft[ref]Becky E Conekin, ‘The Autobiography of a Nation’: The 1951 Festival of Britain, (2003), pp. 94-95.[/ref]. Original designs for all the interior exhibits are held at The National Archives.

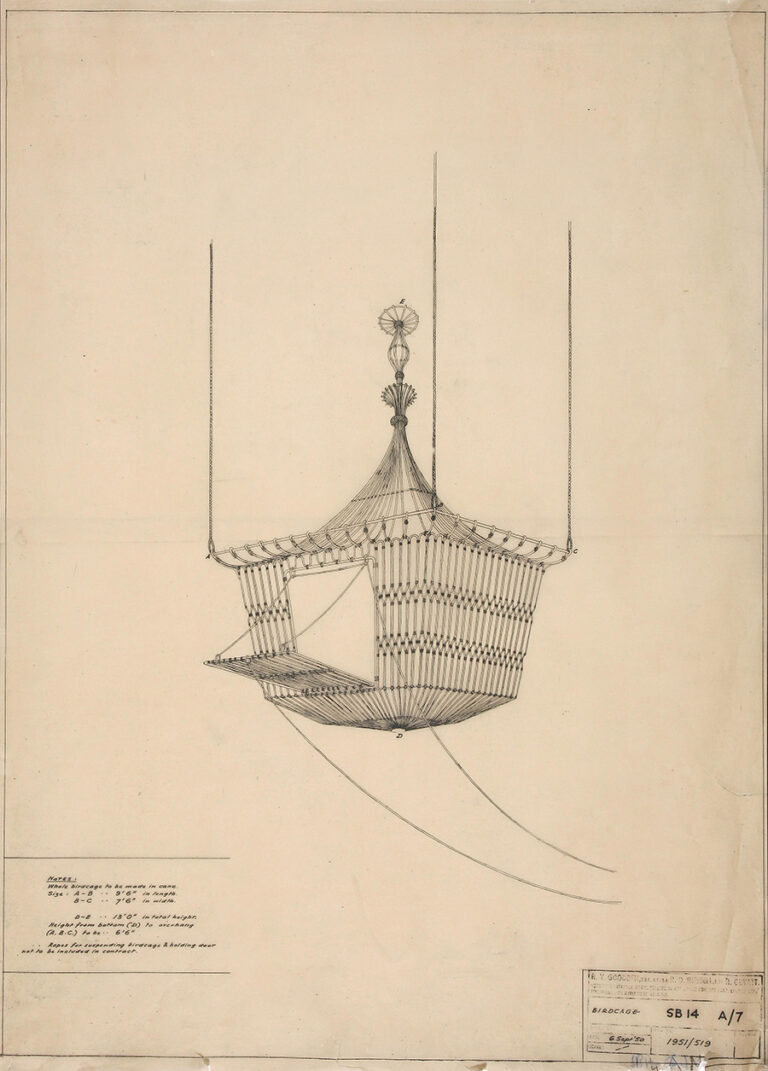

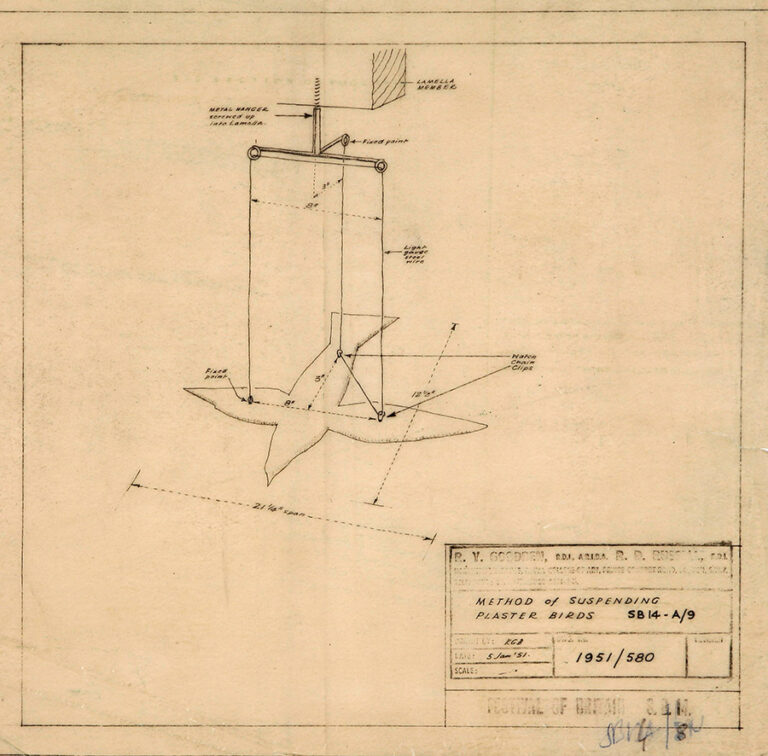

Looking up, you would have seen a beautiful Regency-style wicker birdcage designed by Robert Goodden letting loose a flock of plaster doves, each one suspended intricately from the ceiling.

In the original description of the above photograph, it was noted that ‘due to the heat from lamps one particular dove persists in flying the wrong way in the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion’.

The thing I really love is the birdcage with the flight of doves coming out. There is a lovely drawing of that – I don’t know if my father or Dick Russell drew it but I think it’s much more my father’s style because he was slightly more fanciful in his design.

Henrietta Goodden

The English language and ‘Country Life in Britain’

A flight of stairs led you to the upper level mezzanine where, along the length of the building, you would learn about the English language. Exhibits included the Oxford Lectern Bible, a set of popular Shakespeare plays housed in miniature theatres, a ‘crown of poetry’ displaying metal figures of 12 British poets, and an exhibit enabling visitors to listen to local idioms from across the country[ref]Henrietta Goodden, The Lion and the Unicorn, (2011), p. 99.[/ref].

I found myself working largely on the exhibits with Robert Goodden. At that time he was heading up the School of Silver, but he and I we designed the model theatre and walkways inside. He was a delight to work for. Largely it was designing exhibition cases and the interior fittings that I got involved in with Robert. I had frequent visits to the site and, if you’re surrounded by the destruction of bombing, to see all this rising up was really quite something.

Ray Leigh

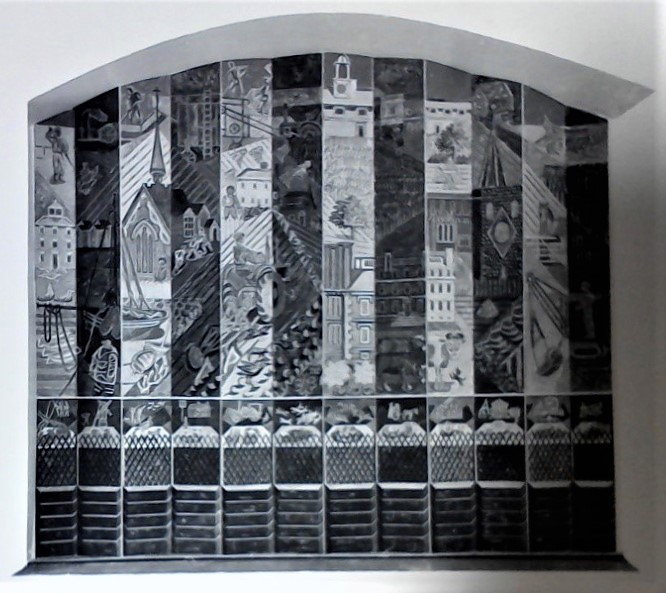

Covering the entire end wall of the pavilion was an enormous mural titled ‘Country Life in Britain’ by Edward Bawden. It showed rural activities in different areas of the country including scenes of coastal life, agriculture and mining.

It really comes through as a celebratory and light-hearted experience, showing people how to enjoy life again. There was the enormous mural at the end by Edward Bawden which used quite bright colours and was very high. You could look at it from different levels; you could look at it from the mezzanine, you could look at it from the staircase and you could view it from the back of the pavilion and it must have been quite dramatic I think.

Henrietta Goodden

The mural was disassembled when the Festival site was closed and it was designated for permanent preservation. However, sadly it has since been lost and it is still a mystery what became of it. To find out more about the preservation and loss of the mural, please read our blog ‘In search of Edward Bawden’s mural ‘Country Life’.

British humour, freedoms and skills

Continuing our tour of the pavilion, a set of stairs at the end of the mezzanine would take you down to the ground floor, allowing inspection of the mural from different angles. A display on British eccentricity and humour was next at the bottom of the stairs, with a large model of the White Knight on his horse, inspired by John Tenniel’s illustration from Alice through the Looking Glass[ref]Ibid., p. 106.[/ref].

I think it was all very tongue-in-cheek. People have did have a conventional view of what the British were like and the pavilion wasn’t making fun of it, it was celebrating the fact that perhaps we are a bit eccentric as a nation.

Henrietta Goodden

Most of the ground floor was devoted to the subject of British freedoms, with freestanding exhibits on freedom ‘of worship’, ‘democracy’ and ‘under the law’. These were backed by a mural, ‘The Freedoms’, painted by Kenneth Rowntree.

Both the displays on the English language and on British Freedoms demonstrated an odd contradiction. The global spread of the English language was celebrated, however the reason for this spread, the British Empire, was not mentioned. Similarly the importance of British freedom was proudly asserted, while Britain’s history of denying freedoms to its colonial subjects was also sidestepped[ref]Harriet Atkinson, The Festival of Britain: A Land and its People, (2012), p. 154.[/ref].

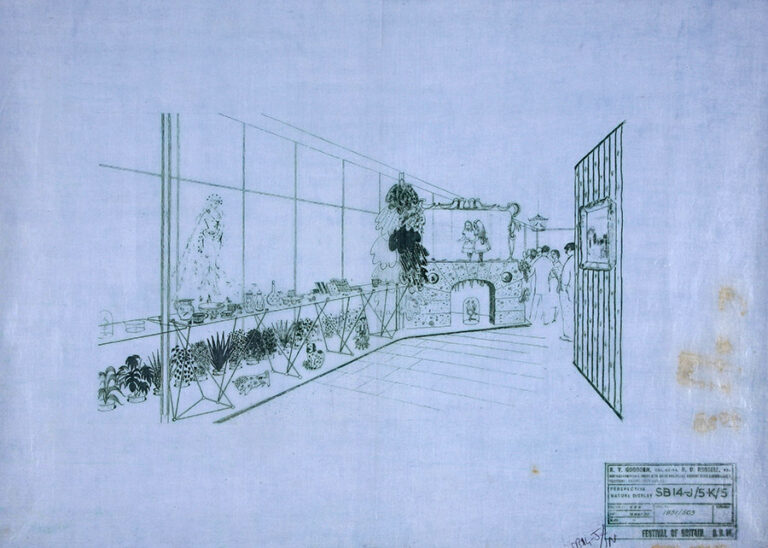

A display of exhibits celebrating British craftsmanship ran along the north-eastern wall, including items of furniture, pottery, glass, textiles and metalwork. This display also carried the theme of nature, attempting to show how craftsmen, artists and designers were inspired by the natural world. A display of British plants on a shelf against the front glass wall of the pavilion perfected the theme.

Light, air and open space

The use of large plate glass as an architectural feature was a very modern and exciting aspect of the design of many of the Festival buildings – a design feature that is at the heart of contemporary design today. It was perhaps used most successfully and strikingly in the glass front wall of the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion. However, it did cause problems, with multiple visitors not seeing the glass and colliding with it. This led to the designers erecting a table display in front of it to act as a barrier[ref]Henrietta Goodden, The Lion and the Unicorn, (2011), p. 115.[/ref].

The final stop on the tour (and, after a long day on one’s feet, perhaps the most important one!) was the restaurant attached to the pavilion and set in a beautiful garden.

One of the key design legacies of the Festival of Britain, and the Lion and Unicorn in particular, was the use of open spaces, inside and outside, to maximise light and air for pedestrian visitors.

The outside atmosphere of the Southbank must have been like an enormous playground, which I think was a very happy thing to happen there by the river – and will happen again. It was the outside as well as the inside that was inspirational to everybody. With COVID-19 and with everyone now becoming more interested in designing exterior spaces, it’s all very relevant.

Henrietta Goodden

Legacies of the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion

The Festival of Britain came to an end in September 1951. The new Conservative government led by Winston Churchill, perhaps feeling the Festival was visible as a project of the previous Labour government, was determined to dismantle the buildings and clear the site quickly. There was some discussion over whether the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion could be re-erected on a site opposite the Victoria and Albert Museum. However, in the end the funds could not be raised to make this a reality[ref]Ibid., p. 123.[/ref].

After the Festival, Robert Goodden continued as Head of the School of Silver at the Royal College of Art. For the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953, he designed the damask hangings for Westminster Abbey and three years later, he also designed a silver kettle, commissioned by the Duke of Edinburgh as a gift for the Queen[ref]’Robert Goodden’, The Guardian (accessed 7 May 2021).[/ref].

Dick Russell ran his own practice and worked on projects including the interior design of the new Coventry Cathedral. He also worked together with Ray Leigh on various projects. They both worked closely with the furniture design firm run by Dick’s elder brother Gordon Russell, and in 1967 Leigh was appointed Design Director[ref]’Six Decades’, The Gordon Russell Design Museum (accessed 7 May 2021).[/ref].

It was a career forming moment – I must have done a few things right because when I came out of the Architectural Association, Dick Russell asked me to work with him. I jumped at the opportunity because it was a small office, hands on, you saw the principles on a regular basis.

Dick and I were in partnership and did a wide range of work. We designed the interior of the SS Oriana and I think it was the first time designers had been totally involved in something like that. We also did the Greek Galleries at the British Museum. It was always a very varied and interesting trail of work.

Ray Leigh

Henrietta Goodden taught fashion design at the University of Kingston and (following in her father’s footsteps) the Royal College of Art. While at the College, she began researching its history, culminating in four books: Camouflage and Art; The Lion and the Unicorn; Robin Darwin; and Wendy, Janey, Joanne and Madge.

Everyone who worked on the Festival was a good qualified designer who probably would have been quite high profile if it hadn’t been for the war and having to be in the services. I think it was a really important period in terms of design, and I think people do appreciate it now. In the last 10 years people have got much more interested in that mid-century period of design, so lots more people know about it than did even ten years ago.

Henrietta Goodden

I was born on 31st of March in Guildford in 1951.

I now live in Cobden in South West Victoria in Australia.

I Have throughly enjoyed reading all the articles on the national archives . I intend to go to my local library and try and get the books you have mentioned.

Thankyou .

Does anyone know what happened to the Shakespeare miniatures designed by Goodden and Leigh? Are they still in existence?

My father was a sign writer and painter at the Festival site during its construction, but it was before I was born, so I’ve no actual recollection of it, just his memories passed down over time. I’ve searched for years for some photo evidence of him at work there, but sadly to no avail. Reading as much as I can about the event helps a bit with that disappointment though, as I can visualise where he was and what he was involved with.

Trivial, perhaps; but one memory of the Festival as a six year old was tasting my very first hot dog on the South Bank!