Seventy-four years ago today, The Empire Windrush landed at Tilbury Docks in Essex carrying 1,027 passengers, with 802 giving their last country of residence as somewhere in the Caribbean.

These details, as well as many others, are captured in the ship’s passenger list held at The National Archives – a document which has arguably become one of the Archives’ most iconic and sought-after records (see footnote 1). But The National Archives also holds the lists of the lesser-known ships also carrying post-war migrants from the Caribbean that pre-dated the Windrush. Like those who Kamau Brathwaite dubbed ‘the arrivants’ (footnote 2) travelling aboard the Windrush, they too were keen to make a contribution towards rebuilding what was often seen as the ‘mother country’ after the Second World War. Often holding on to what Muhammad Anwar would describe as the ‘myth of return’, their self-image was typically that of sojourners rather than settlers – people who would work for a few years before returning to their homeland in a more prosperous position (footnote 3).

To mark the 74th anniversary of the Windrush migration, this blog will provide a brief introduction to the post-war ships that came to Britain prior to the Windrush, albeit without the media attention that the latter would receive in the following year. It will also attempt to provide some brief guidance on where to begin researching Black British history at The National Archives.

The first of these lesser-known ships that arrived in the post-war period was an ex-troop ship called the SS Ormonde, which docked in Liverpool on 31 March 1947 – more than a year before the Empire Windrush. The passenger list informs us that 241 people made the journey, including 11 stowaways and six distressed seamen (footnote 4).

The list shows a diverse range of skills and professions among the passengers, who included carpenters, engineers, plumbers and more. However, as a result of the colour bar in Britain, many could only find employment in the least desirable areas of the economy, in work that was typically semi- and unskilled, with low wages and poor conditions. Indeed, a study by the sociologist Ruth Glass carried out between 1958-59 showed that 55% of Caribbean migrants experienced job downgrading after their arrival (footnote 5).

Among the travellers that can be seen in the passenger list above is Ralph Lowe, the father of the award-winning poet, Hannah Lowe. Her chapbook of poetry, which was inspired by and takes its title from the vessel, informs us that Ralph paid £28 for his ticket (footnote 6).

Following the Ormonde was the Almanzora, which docked in Southampton on 21 December 1947. It brought 200 Caribbean passengers to the UK, many of whom were former RAF service personnel who had served during the Second World War. Like the Ormonde before it, the passenger list shows a diverse range of skills and professions.

Beginning with the names Olga and Jacqueline, it also highlights the large number of Caribbean women making the journey and their critical role in the establishment of Britain’s post-war Black communities, while at the same time challenging some of the accounts of all-male travellers on the earlier vessels (footnote 7).

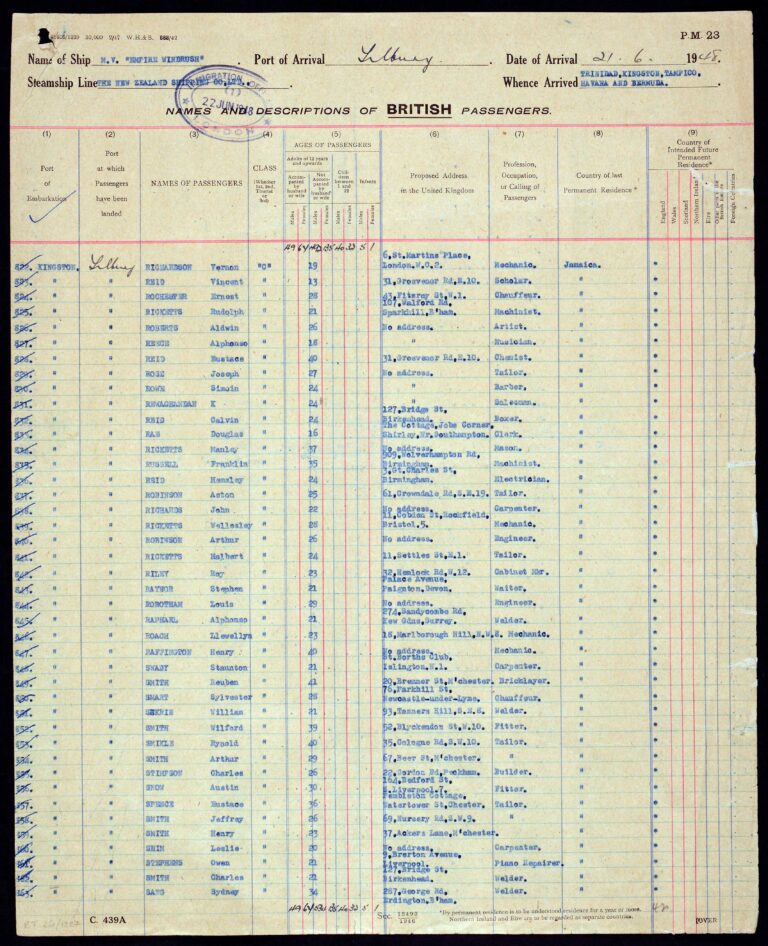

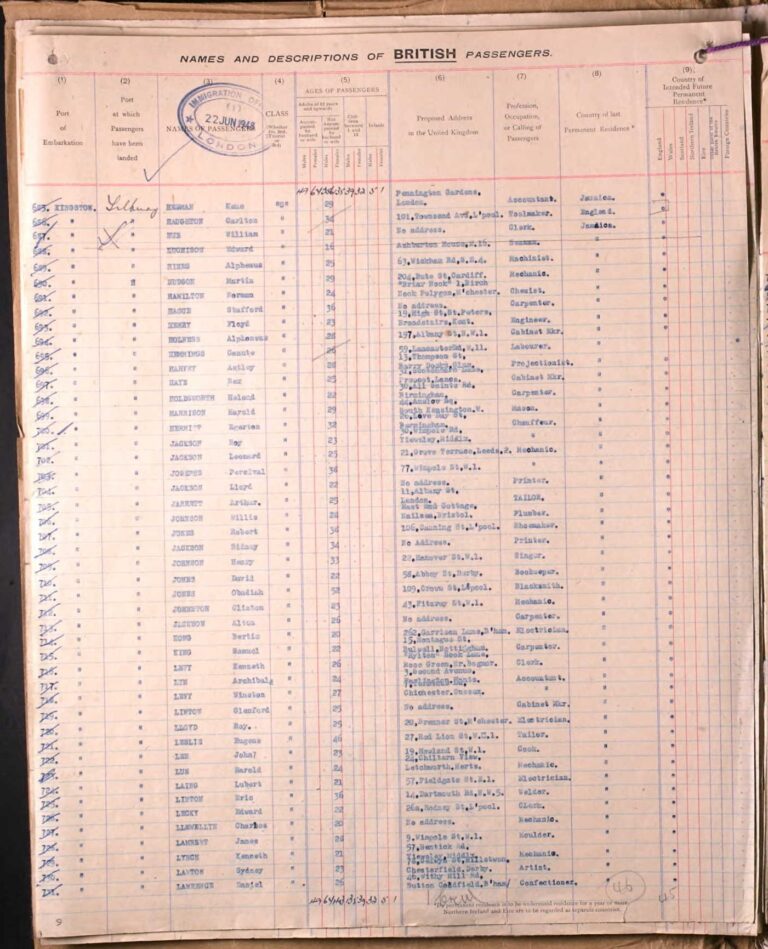

Then, most famously of all, came the Empire Windrush. Although the date of the ship’s arrival is often given as 22 June 1948, a day which is now marked annually as ‘Windrush Day’, the passenger list actually records the date as 21 June. This has led some researchers, such as Matthew Mead, to suggest that the ship spent a night in port before disembarkation (footnote 8).

Among the names listed above is that of Aldwin Roberts, better known as the calypsonian, Lord Kitchener (or even ‘Kitch’ as Anthony Joseph put it in his recent biography of the calypso icon), who famously sang ‘London is the place for me’ for reporters upon his arrival (footnote 9). It is also notable that, like many others, he wrote ‘no address’ for ‘proposed address in the United Kingdom’. Many of these migrants would find accommodation in the air raid shelters underneath Clapham South underground station, which would at least delay their confrontation with some of the well-documented horrors of finding a place to stay as a Black (or indeed Irish) person, in the ‘host’ country (footnote 10).

Another well-known name – that of Sam King, who served as an engineer in the RAF during the Second World War, and who would eventually become the first Black mayor of Southwark – appears on the above page, highlighting again the diverse talent and rich contributions that these settlers would make to British society.

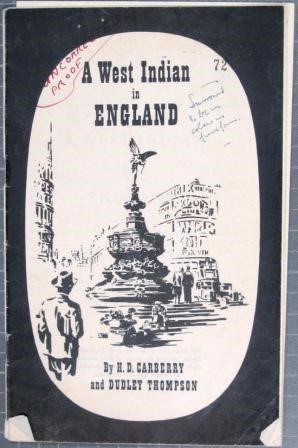

The passenger lists held in record series BT 26 only scratch the surface of the records at The National Archives that relate to post-war migration. This image (left), for instance, shows the draft cover page of a pamphlet entitled ‘A West Indian in England,’ commissioned by the Central Office of Information in 1949 to show potential migrants what to expect in what’s described as ‘unknown and darkest England’ (footnote 11). The booklet, co-authored by Dudley Thompson, one of Britain’s first black pilots, who served during the war and would go on to become a leading politician in Jamaica, hints at the broader wealth of resources held at The National Archives.

As the official archive of the UK government, the records held at The National Archives do largely represent the voice of officialdom. However, when combined with resources from community archives such as The Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, The Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre and Education Trust in Manchester, and The George Padmore Institute, they can help researchers piece together a much more rounded picture of the lives of the sojourners/settlers, and provide a more detailed insight into themes such as the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors of migration, the experiences of women, the lives of the children and grandchildren of the pioneers, and much, much, more.

The National Archives’ research guides to Black British social and political history in the 20th century, Immigration and immigrants, and Passengers, provide important starting points for navigating the records held. Another useful resource is the Black Asian and Ethnic Minority Histories Finding Aid, which contains a hyperlinked list of The National Archives’ current resources about Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic histories available on the website.

Footnotes

- The National Archives holds the UK’s surviving inward and outward passenger lists from the late 19th to the mid-20th century, when air travel became more common. For more information see The National Archives’ research guide to Passengers.

- Brathwaite, Kamau (1981) ‘The Arrivants: A New World Trilogy’ (Oxford University Press).

- Anwar, Muhammad (1979) ‘Pakistanis in Britain’ (Heinemann).

- ‘Distressed Seamen’ refers to sailors without a ship in a foreign port. The sailors may have lost or missed their vessel for a number of reasons, including: enemy action, sickness, drunkenness, imprisonment, jumping ship and so on. For more information see, Lowe, Hannah (2014) ‘Ormonde’ (Hercules Editions).

- Glass, Ruth (1960) ‘Newcomers: The West Indians in London’ (Harvard University Press), p.31, cited in Hiro, Dilip (1992) ‘Black British, White British: A History of Race Relations in Britain’ (Paladin), p.26. This prejudice of course didn’t just apply to employment, and a year after the landing of the Ormonde, Liverpool would see three nights of anti-Black rioting, in the summer of 1948 (for more information, see: Fevre, Christopher (2021) ‘Race and Resistance to Policing Before the “Windrush Years”: The Colonial Defence Committee and the Liverpool ‘Race Riots’ of 1948′ (Twentieth Century British History), 32:1, pp. 1–23.

- Low, Hannah (2014) ‘Ormonde’ (Hercules Editions).

- For a discussion of this, see: Mead, Matthew (2007) ‘Empire Windrush: Cultural Memory and Archival Disturbance’ (MoveableType), Vol.3, p.11

- Mead, Matthew (2007) ‘Empire Windrush: Cultural Memory and Archival Disturbance’ (MoveableType), Vol.3, p.117. Mead also points out further inconsistencies between much of the literature about the Empire Windrush, and the information given on the passenger list itself. Perhaps most notably he points out that the number of 492 Caribbean migrants often said to be aboard, conflicts with that given on the list (cf. ibid: 115).

- For more information, see: Joseph, Anthony (2018) ‘Kitch: A Fictional Biography of a Calypso Icon’ (Peepal Tree Press).

- Cf. Fryer, Peter (1984) ‘Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain’ (Pluto) p.375; Phillips, Mike and Phillips, Trevor (1998) ‘Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain London (HarperCollins) p.81-94; South London Press and The Voice (1988), ‘Forty Winters On: Memories of Britain’s Post War Caribbean Immigrants’ Lambeth Council.

- For more information, see, Orme, Jenni (2013) ‘Unknown and darkest England’.

Dear Blogers

It is regertable that , during The Refugee Week,you did not refer to refugees from Central and Westren Eurpoe who have fled before and during world war II to spain and Portugal and some even end up in to Morocco and Alg’e due to harsh British Immegration policy at that time.

You may want to this expand the horizons of your readers.

Daniel

Are there any passenger lists from the RMS ORMONDE sailing from Gibraltar to Greenock in 1943?

I don’t have the exact date yet, but I’m working on that.

Was there ever a ship called the SS Sorenta? Or something similar?