We like to think of archivists as not just incredibly knowledgeable, resourceful and hard-working but also as gentle, cake-loving souls. But was that always so?

In this post Ed Woodhouse explores a more unseemingly episode in the history of record-keeping in this country. Ed is a PhD Student at the University of East Anglia, where he is examining the Chancery Rolls of King John (1199-1216). He spent 12 weeks at The National Archives earlier this year on a placement with the Medieval Records team.

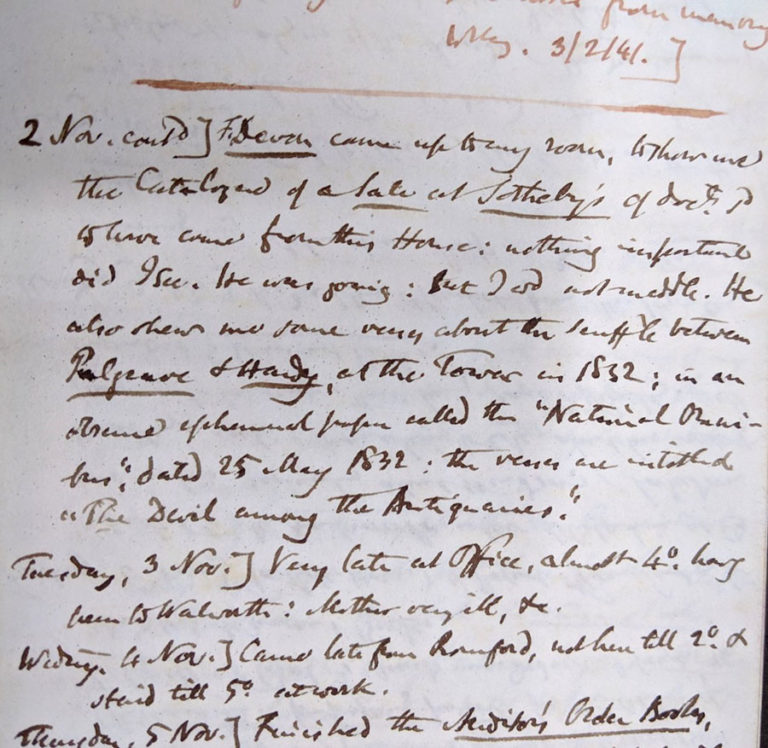

In an entry in his private notebook dated 2 November 1840 the antiquary William Henry Black recorded a visit from Frederick Devon, a fellow antiquary who worked as a clerk in the Chapter House at Westminster. Devon had visited his rooms to show him several items of interest, including ‘an absurd ephemeral paper called the National Omnibus [and General Advertiser], dated 25 May 1832’ in which were printed ‘some verses about the scuffle between Palgrave and Hardy at the Tower in 1832’. This physical clash appears have taken place in April 1832 after years of verbal and written attacks[ref]The opening chapter of Jack Cantwell’s history of the Public Record Office provides an excellent account of the beginning of Hardy and Palgrave’s quarrels, as well as the other disputes and controversies involving those early archivists: J D Cantwell, The Public Record Office 1838-1958 (London, 1991), pp. 1-5.[/ref]. The Tower of London has undoubtedly witnessed a significant number of scuffles over the years, both as fortress and tourist destination. The identities of the two men involved, however, must make this particular fight one of the more curious and unlikely to have occurred within that fortress’ walls.

The two participants, Francis Palgrave and Thomas Duffus Hardy, are themselves very significant figures in the history of record-keeping in Britain and in the genesis of The National Archives. Palgrave was the very first Deputy Keeper of the Public Record Office, from its foundation in 1838 until his death in 1861, before which he had held the post of Keeper of Records at the Chapter House from 1834. He was also heavily involved in the work of successive Record Commissions between 1800 and 1837, which preceded the formation of the Public Record Office[ref]For a full discussion of the Record Commissions and the passage of the Public Record Office Act (1838), see P Walne, ‘The Record Commissions, 1800-1837’, Journal of the Society of Archivists 2 (1960), pp. 8-16.[/ref].

Hardy, his opponent in 1832, was at that time a clerk at the Tower record office and was also regularly employed by the Commission. The younger, more junior record officer, he would eventually succeed Palgrave as Deputy Keeper in 1861, having initially lost out to him for the role in 1838.

The fight at Hardy’s workplace in the Tower was a significant factor in their long-running and bitter rivalry, although the animosity likely began around 1823. Hardy, along with his brother William and several other young clerks, had taken on some transcribing work for Palgrave outside office hours, but had quarrelled over the terms of their remuneration[ref]Cantwell, The Public Record Office, p. 3.[/ref].

The most in-depth description of the fight itself was written by the novelist John Cordy Jeaffreson in 1894, long after both protagonists had died. Jeaffreson still provides us with a blow-by-blow account. Palgrave had arrived at the Tower to confront Hardy over some perceived wrongs. Angry about these ‘false accusations’, Hardy sprang from his chair and, landing a blow on Palgrave’s left cheek, knocked him to the ground. Then, when Palgrave returned to his feet and advanced on Hardy with arms raised, Hardy is again said to have floored him, this time hitting him below his right eye, before Palgrave retreated. Some caution should be applied to Jeaffreson’s account, considering his flair for the dramatic and also that his information must have been second-hand and likely sourced from one side of the dispute – he was only born a year after the fight itself and was mentored by Hardy later in life.

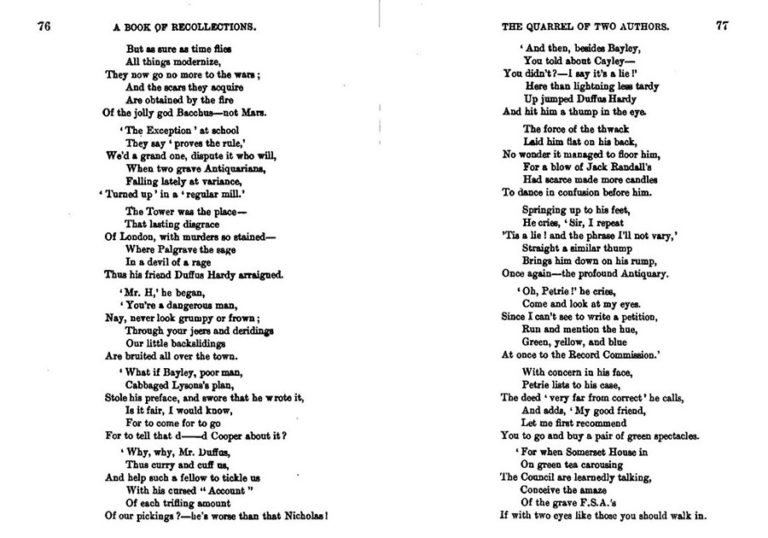

It does appear, however, that Palgrave did indeed come away from the fight with two black eyes. Those verses referred to in Black’s notebook were written in the aftermath of the fight and mercilessly mocked Palgrave’s appearance in the following days. A copy of the poem was printed along with Jeaffreson’s account, and from the reference to the same verses in William Black’s notebook it seems they were still circulating amongst Hardy and Palgrave’s colleagues nearly ten years later, even after Palgrave’s appointment as Deputy Keeper.

Despite the goading, Palgrave, somewhat surprisingly and apparently against his friends’ advice, did not demand the satisfaction of a duel with Hardy. In general, Hardy, despite throwing the first punch, does not seem to have suffered any immediate consequences from the fight. His superior at the Tower, Henry Petrie, defended him from Palgrave’s complaints. For his part, Palgrave refused to apologise for – or withdraw – his accusations against Hardy.

Over the next few years the two men appear to have avoided each other as best they could. It cannot have been easy, however, as Palgrave found himself working for the Record Commissioners, calendaring and sorting miscellaneous records in the Tower between March 1833 and his appointment as Keeper of Records at the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey in May 1834.

The relationship does not appear to have got any easier after the formation of the Public Record Office, when Palgrave was appointed Deputy Keeper ahead of Hardy. Although Hardy would not have been pleased with Palgrave’s appointment, he had probably expected it. Subsequent stories that Hardy felt cheated out of the appointment were likely a misrepresentation arising from Jeaffreson’s rather exaggerated account of events, including a suggestion that Hardy, when required to engage with his new superior on official business, would approach him ‘as though he were a mere piece of official furniture, and said in the fewest possible words what duty required him to say’[ref]John C Jeaffreson, A Book of Recollections, vol. 2(London, 1894), pp. 83-4.[/ref]. Whatever truth is in these stories it is likely an uneasy truce held for the remainder of Palgrave’s life.

Indeed, the scuffle at the Tower, which William Henry Black and Francis Devon were discussing eight years later, clearly had consequences beyond the bruising of Palgrave’s face. We are unfortunately left to guess at what exactly Palgrave said to inspire such fury. Although Jeaffreson narrated how Palgrave confronted Hardy at the Tower over some perceived wrongs, he declined to give more details beyond stating that Palgrave believed Hardy had ‘made mischief between the Record Commission and certain gentlemen working under them’[ref]Ibid., pp. 72-3.[/ref]. We know that Palgrave was facing criticism from several other antiquarians regarding his employment under the Record Commissioners, in particular over the expense involved in his editing of the Parliamentary Writs[ref]The two men most involved in this ‘campaign’ against Palgrave were Nicholas Harris Nicolas and Charles Purton Cooper, the secretary of the final Record Commission from 1831: Cantwell, The Public Record Office, pp. 2-3.[/ref]. There are several entries in the minute books of the Commission for the months leading up to Hardy and Palgrave’s fight which perhaps shed some light on the events which led to the confrontation.

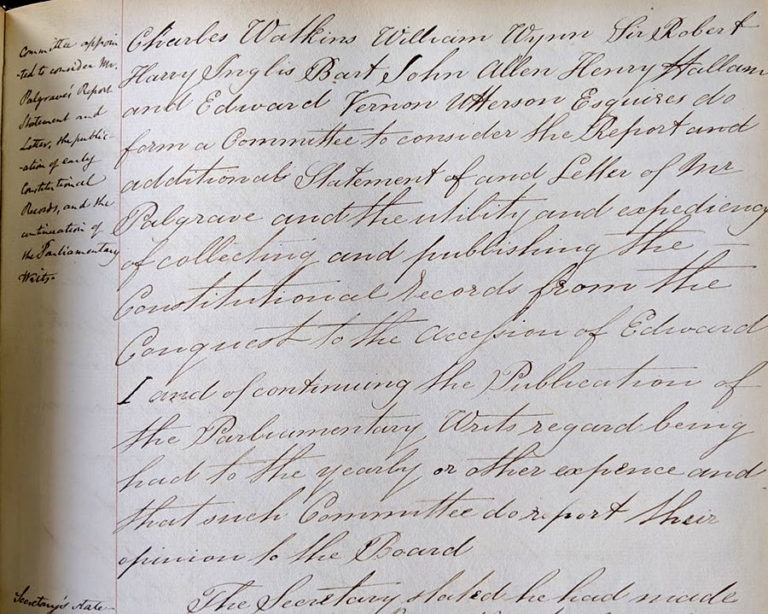

A progress report dated 21 March 1831 shows that when the sixth commission began, Palgrave was working on editing the ‘Rolls of Parliament, etc.’, which had emerged from his editing of the Parliamentary Writs. Between March and July of the same year the commissioners had ordered Charles Purton Cooper, the secretary, to provide a ‘proper estimate’ of the cost and time required to complete a second volume of Parliamentary Writs, and they had requested Palgrave to provide an estimate for the printing of the ‘Pipe Rolls, Scutage Rolls and Notices of Great Council and other materials for the constitution of England’ as part of his ‘Rolls of Parliament’ project. In July the commissioners ordered a sub-committee to be formed to consider whether to continue work on the Parliamentary Writs[ref]PRO 36/11, pp. 22-30, 35, 41.[/ref].

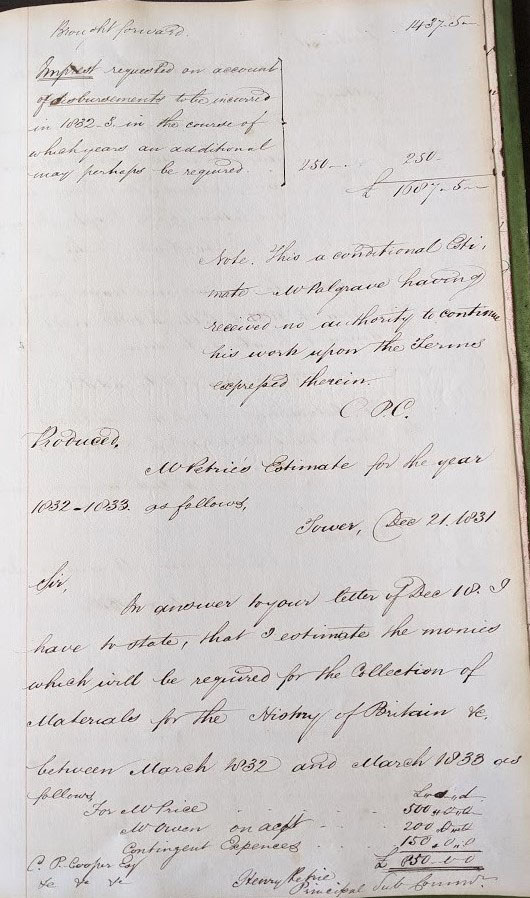

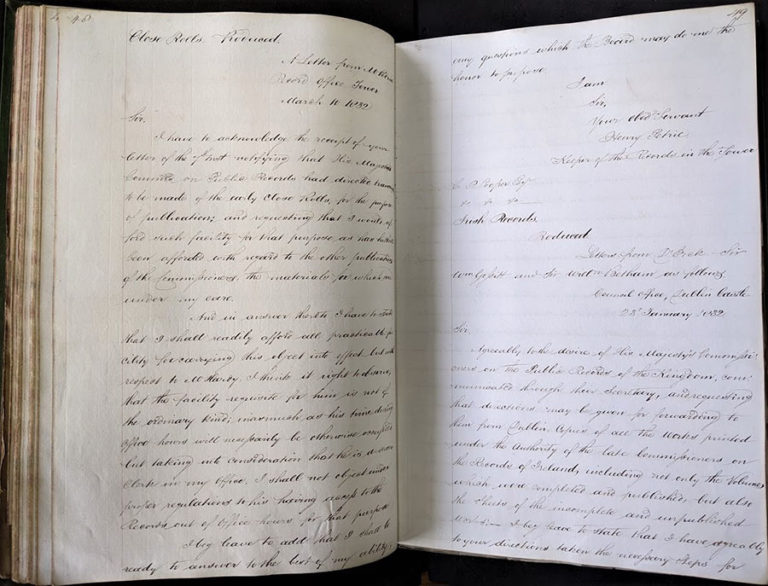

With his work on the Parliamentary Writs under threat it appears that Palgrave’s focus had turned to his newer project. At a board meeting in December 1831 an estimate was made by Palgrave for his work on the ‘Constitutional and Parliamentary Records’ from March 1831 to 1832. An additional note made alongside this estimate, however, states that Palgrave had ‘received no authority to continue his work upon the terms expressed therein’. In the minutes for the same meeting is another note, commenting that the secretary had made arrangements with ‘Mr Hardy one of the clerks at the Tower for commencing printing of the close rolls’[ref]PRO 36/11, pp. 221-2.[/ref]. As such, Hardy was approached to start working for the Record Commissioners by Palgrave’s enemy Charles Purton Cooper, whilst Palgrave himself was struggling to obtain payment for his work on his new project and with his old project under threat of being discontinued.

In February 1832 the Commissioners agreed to compensate Palgrave for his work in the last year according to his arrangement with the previous Commission; however, he was given notice that the ‘mode and rate’ of his payment in future would depend on the board’s decision[ref]PRO 36/12, pp. 1-3.[/ref]. Meanwhile the committee formed to look into Parliamentary Writs had not yet made a decision. It was not until the end of June 1832 that an order was given to Palgrave to continue his work, although the committee had still not concluded their investigation. Finally, on 9 August the committee formally agreed that the project should go ahead, although no decision had been reached on the terms of Palgrave’s remuneration[ref]PRO 36/12, pp. 66, 82.[/ref]. Palgrave’s project concerning the ‘Constitutional and Parliamentary Records’, however, disappeared from the records of the Commissioners after they agreed to pay him for his work in 1831. Not long after, on 10March 1832, the official order was given for Hardy’s edition of the Close Rolls to be produced. By the end of the following month Palgrave and Hardy were brawling in the Tower[ref]PRO 36/12, pp. 48-9.[/ref].

We cannot be sure exactly what Palgrave accused Hardy of at the Tower that day. Palgrave believed Hardy had been working against him to undermine his standing with the Record Commissioners. It seems probable that Palgrave felt Hardy had played a part in his constitutional records project being rejected. It cannot have helped that Hardy appeared to have benefited from Cooper’s assistance around the same time. It is also possible that Palgrave felt Hardy had been involved in the attacks against his Parliamentary Writs, although the long-running nature of this dispute suggests it was less likely to be the catalyst for the fight alone. Whatever the cause, the resulting hostility between Palgrave and Hardy had a long-lasting impact on the leadership of the Public Record Office throughout its early years.

Thank you very much for this interesting paper. Could there be more information in these 1832 Tracts on the Record commission? some of which are available on Google Books.

Source: https://www.worldcat.org/search?q=%22Tracts+on+the+Record+commission%22&fq=&dblist=638&qt=sort&se=yr&sd=asc&qt=sort_yr_asc