This blog includes letters on temporary display at The National Archives as part of Stories Unboxed. During September, you can see them for yourself by visiting the first floor of our building in Kew during opening hours.

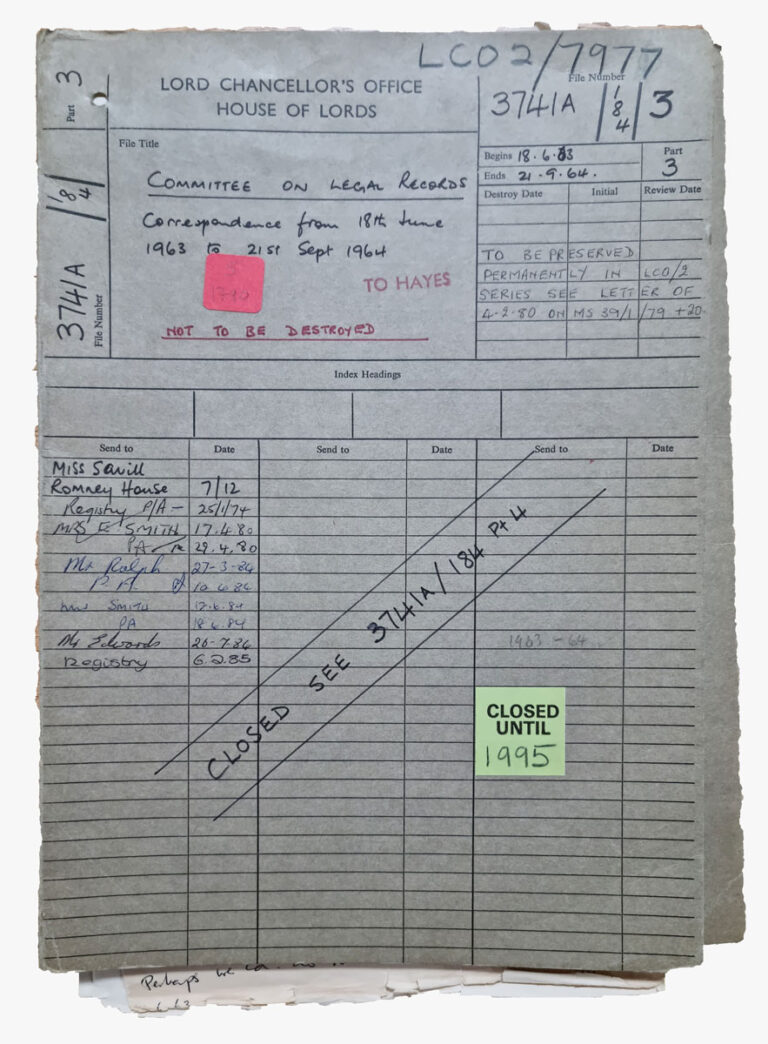

Appointed by the Lord Chancellor in January 1963 and reporting to Parliament in August 1966, the Denning Committee on Legal Records’ task was to:

- examine the court records existing and accruing in various courts and at the Public Record Office (The National Archives’ predecessor)

- recommend which classes of records should be permanently preserved and for what purposes

- advise on retention periods for records not selected for permanent preservation

- consider whether any of the records considered should be microfilmed

Following the extension of its terms of reference in 1964, the Committee’s considerations embraced almost all criminal and civil court records for England and Wales. It faced a Herculean task and not even its most vehement detractors could deny the scale and difficulty of its endeavours. Its final report, which was published in 1966, [ref]Cmnd 3084. This was despite the reservations of the Public Record Office regarding publication. See letter of Denham to Thesiger (21 June 1966) in LCO 2/7978. [/ref] was both comprehensive and radical in its recommendations.

Limiting preservation

The report attracted relatively little attention from lawyers. As one legal historian had wryly remarked, ‘I do not think that the readers of the Modern Law Review will rise in wrath: like the clergyman and sin, their attitude to history is that they are against it.’[ref]Milsom to Johnson (12 April 1967) in PRO 42/27.[/ref]

In other quarters, however, it was greeted with consternation, not least because of the scale of destruction that it mandated. The Committee celebrated this, writing, ‘if our proposals are carried out, the PRO alone will be relieved of 200 tons of records, occupying 15,000 feet of shelving’.[ref]Cmnd 3084, pvii. [/ref] Of the 722 classes of records considered only 130 were selected for permanent preservation while samples of a further 83 were to be permanently preserved.

Understanding the approach

The Committee was a creature of its time. Many of its members had previously participated in initiatives to revise record destruction schedules as part of wartime economies. Many would also have collaborated in the wholesale destruction of accumulations of papers in offices and homes as part of efforts to clear attics and basements to reduce fire risks during the Blitz.

Moreover, being predominantly highly pragmatic court officers, lawyers, civil servants, and officers of the Public Record Office,[ref]With its historic focus upon its medieval and early modern holdings.[/ref] they were often sceptical of the value of modern legal records. The report reflected this, describing them as being often ‘quite valueless’ or ‘uninformative and incomplete’ and little used.[ref]Cmnd 3084, p2.[/ref]

Worse still, modern legal records contributed greatly to pressures on storage space at the Public Record Office at a time when the pressure on public finances militated against the allocation to it of additional resources for record storage or reader facilities.[ref]See, for example, the correspondence in T 227/2717.[/ref] Between 1875 and 1935, it had accessioned 4 shelf miles of civil court records, and a further 6 shelf miles were occupied by post 1858 original wills.[ref]Cmnd 3084, p2.[/ref]

This setting, with its acceptance of both the inevitability and the desirability of extensive destruction of records, shaped the entire creation and work of the Committee. Lord Denning, a judge who was rapidly acquiring a reputation for ‘getting the job done’, was a desirable chair, not only because of the office he held, but also because he was reported as feeling ‘strongly that it is most necessary not to retain a lot of records which no one wants to see.’[ref]Boggis-Rolfe to Coldstream (27 September 1962) in LCO 2/7975.[/ref] Another key member of the Committee considered that the Committee’s ‘object was to advise how to reduce the quantity of useless records’.[ref]Denham to Thesiger (21 June 1966) in LCO 2/7978.[/ref]

Choosing what to keep – the Committee and its critics

In making decisions about record selection, the Committee followed in the footsteps of the Grigg Committee on Departmental Records.[ref]For its report see Cmnd 9163.[/ref] It determined that legal records should not be permanently preserved solely because they contained information which was useful for genealogical or biographical purposes.[ref]Cmnd 3084, p5.[/ref] The Committee’s most controversial recommendation, the destruction of almost all original wills for the period after 1858, was produced by the application of these principles. It was deeply unpopular, particularly at a time of burgeoning interest in genealogical research, but it was seen as unavoidable given constraints upon space and public finances.[ref]Lord Chancellor Gardiner to Sir Anthony Wagner of the College of Arms (11 October 1966)in PRO 42/27.[/ref]

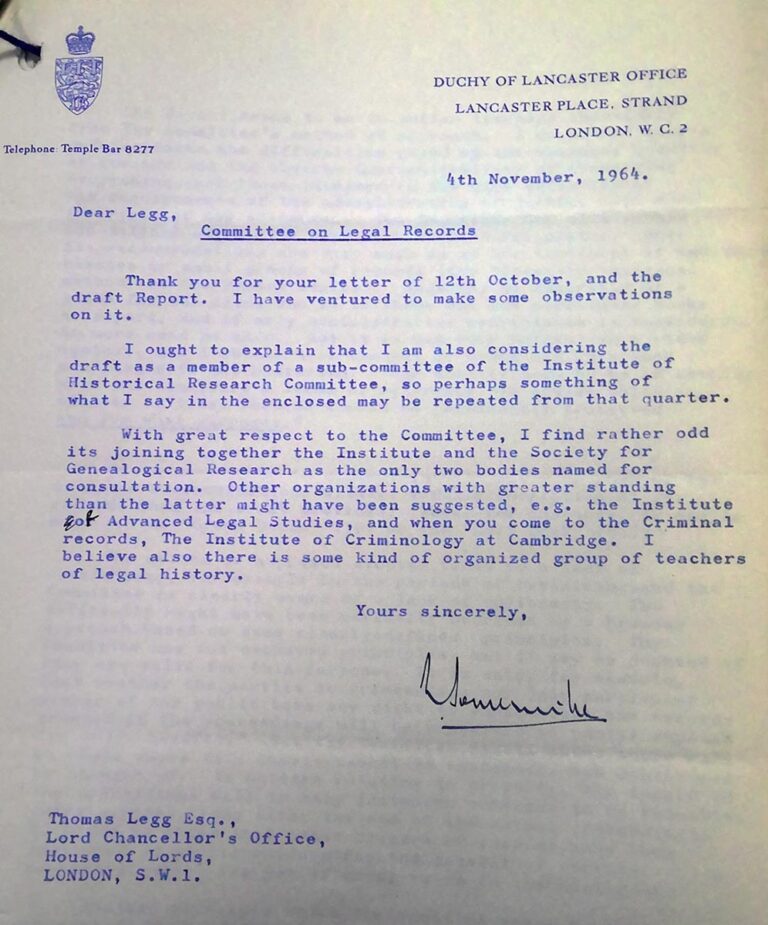

The Committee’s critics argued, both that it had failed to give due weight to the needs of genealogists, and that it had neglected the needs of researchers more generally. They asserted that it had focussed primarily on the needs of the courts and the legal profession, and on the use of the records for current legal purposes. They noted that the Committee’s membership was dominated by the ‘legal interest’ and that, in gathering evidence, it had focussed on information given by courts and court officers. It had only consulted a wider, but still quite limited, constituency of users after it had formulated a preliminary draft of its report. Many of the Committee’s fiercest opponents were convinced, both that this consultation and evidence gathering did not go far enough, and that the selection of those consulted was inadequate and unsatisfactory.[ref]Sir Robert Somerville, Chair of the British Records Association, to Legg as secretary to the Committee (4 November 1964) in LCO 2/7978.[/ref]

This feeling was evidenced in a letter from one such critic, Sir Robert Somerville, Chair of the British Records Association, to the Committee’s secretary Thomas Legg.

Currently on display at The National Archives as part of Stories Unboxed

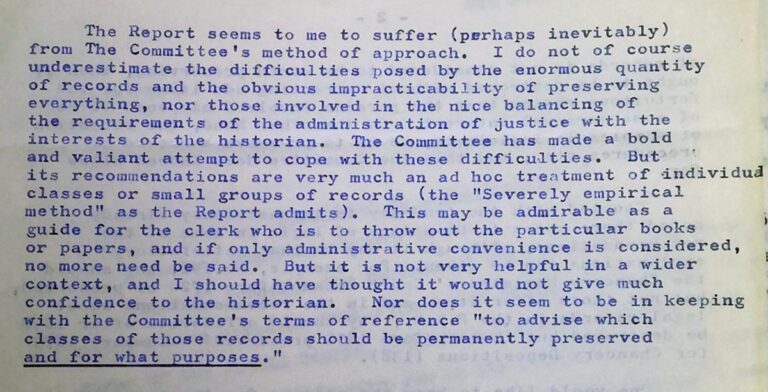

Critics, as seen in Somerville’s letter, were equally trenchant in their criticism of the way in which the Committee had tackled questions of record selection, sampling, and retention periods. It had not adopted a uniform approach, and Somerville accused it of pursuing an ‘ad hoc treatment’ of individual series, and of showing a ‘lack of consistency’, which was ‘not very helpful in a wider context’ and ‘would not give much confidence to the historian.[ref]Sir Robert Somerville, Chair of the British Records Association, to Legg as secretary to the Committee (4 November 1964) in LCO 2/7978.[/ref]

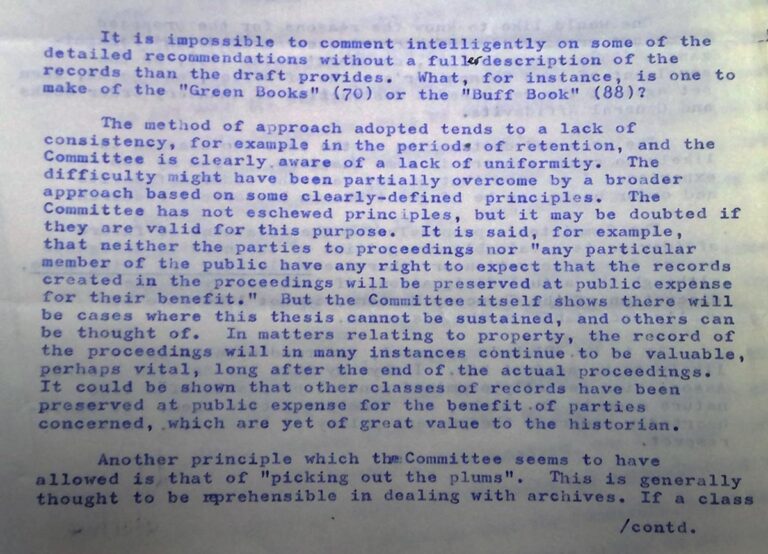

Perhaps most seriously of all, they accused it of permitting ‘picking out the plums’ by selecting certain record samples on the basis that the records in question related to, or were created by, persons of note. Such practice was, they asserted, ‘generally thought to be reprehensible in dealing with archives.’[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

Another principle which the Committee seems to have allowed is that of ‘picking out the plums’. This is generally thought to be reprehensible in dealing with archives.

Sir Robert Somerville

The afterlife of the Denning Report on Legal Records

Such was the scale of the Committee’s recommendations, and so bitter were the recriminations against it, that its report was referred to the Advisory Council on Public Records, which felt compelled to undertake a wider consultation. This prompted one official from the Lord Chancellor’s Office to comment rather waspishly to another that, ‘it’s a great pity the Denning Committee did not consult etc interested parties as the Advisory Council now has to go over much of the same ground.’[ref]See marginal note on Memorandum (1 December 1966) in LCO 2/7983.[/ref] Ultimately, however, the report was largely vindicated, and its recommendations left substantially intact.

As the last detailed and systematic consideration of the selection and archival treatment of legal records in England and Wales, the legacy of the Denning Committee lives on. For historical researchers its significance will be immediately obvious. Record selection policies, together with decisions around cataloguing, access arrangements, and the creation of microform or digital surrogates, determine the resources upon which they draw, and ultimately the stories that they can tell, the narratives that they construct, and the conclusions that they draw in their work.

Perhaps less immediately obvious are the implications of the report for the functioning of the judicial system in England and Wales, and particularly for the principle of open justice as it underpins the Rule of Law. In a legal system which relies extensively (and increasingly) on written process, the ability to access and use court records is essential in allowing citizens to understand and interact with the judicial system.

This is not the only case where records have been destroyed solely because of financial constraints, it continues to this day. The destruction of a large number of murder files have disappeared and files on important cases such as James Hanratty continue to be with-held by TNA, despite the fact that the events happened in 1962. Indeed TNA now close records up to almost 200 years, 100 years used to be the maximum. The result of this and Denning is that the whole story is with-held or destroyed, either accidentally or not.

Archival policy has operated on the basis of selective preservation of public records since the Public Records Act 1878, and the practice of selective retention was embedded within the Public Records Act 1958. The Denning Committee carried out its review work in that context. Issues of resource and storage space were considered alongside the perceived value or interest of the records for research purposes. Given that research interests and methodologies change over time, it is inevitable that we will sometimes regret record selection decisions made in the past.

The question of access to records is distinct from the question of record selection. The legal regime regulating access to public records has changed significantly over time, so access and closure periods may differ depending on when records were transferred to The National Archives. Access is now governed by Freedom of Information Act 2000, which for personal data defers out to Data Protection. In accordance with the Data Protection 2018 and previous Data Protection legislation, personal data in the records that has been reviewed as not suitable for public access is generally closed for the lifetime of that person. A lifetime is assumed to be 100 years from date of birth.

This is happening today in education, under the supposed guidance of the Data Protection Act 2018 & GDPR, where organisations have introduced retention policies and are blindly following them. What has become a fairly standard retention statement is that school records should be destroyed for most students at birth + 25 years (some exceptions). This destruction includes the admissions records. So there will be no record of the student attending the school; any history is lost, and the ability for future researchers to research individuals or groups of individuals. There is an exemption in the GDPR relating to historical research; yet this was not included in the recent Department for Education guidance on Data Protection.

Hello. I am a freelance archaeologist and historical researcher, based in Lancaster. This is a fascinating blog, which I believe touches on areas of research that concern me, such as the use of Lancaster Castle (a Duchy of Lancaster property) throughout the seventeenth to twentieth centuries, until 2011, as a prison. Whilst I believe some records remain with the Ministry of Justice, and others have recently been (or will soon be) opened to inspection at TNA and Lancashire Archives, I wonder what was destroyed in the 1960s that might have been relevant? Is there an accessible list of classes of document that were destroyed, or from which selected items were retained? At least this would draw a line under searches for some documents.

I had this same problem when I was researching First World War Home Front remount (horse training) depots a few years ago, and WWI German PoW camps (which again included Lancaster Castle).

You can often find information regarding the archival history of records and selection policies in the record series and division pages for them in Discovery. Beyond this, you may find it helpful to check the relevant departmental retention and destruction schedules drafted by the originating department. More recent examples are usually published online, while earlier iterations will sometimes have been accessioned to The National Archives as files in the “PRO” series.

We bemoan the losses of various historical libraries due to war, empire changes etc. What of good value was destroyed just because “it did not look good enough at that time”?

As Lord Denning’s most recent biographer I naturally found this blog fascinating. As ever one sees the Denning contradictions. On the one hand, he was a devotee of history, acquired what he proudly considered to be the finest private law library in the land, and kept a very substantial amount of his personal papers which he later passed to the Hampshire County Council Archives (fortunately for later researchers such as myself!). He also took much pride in his role heading public records (the original meaning of his most famous public post, the Master of the Rolls). All those points would, one assume, lead Denning to be anxious to preserve legal and other public records as much as possible.

On the other hand, Denning was usually highly pragmatic, as you’ve observed, and also rather enjoyed ignoring outdated precedent when he thought justice required him to do so. For that reason he dismissed old cases which had not been reported in the official law reports (which in practice means the vast majority) even though some might have significance missed by the not-infallible law reporters at the time. Since there would not be legal value in most old records, one can imagine Denning seeing no merit in their retention, if it was going to be a drain on resources better spent elsewhere including other forms of records. But it was odd and more than a shade blinkered of him not to see any value for social historians. The Spokesman for the Common Man, as Denning was sometimes known, rather let researchers of the history of the common people down.