The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 is usually portrayed solely as a stand-off between the two global super-powers: the USA and the USSR. There were, however, other players in this most deadly of games, not least the Cubans themselves and, perhaps less obviously, the British, who, unlike the USA, retained an embassy in Havana from which to take a view of events at first hand.

In the eye of the storm: The view from Cuba

There was, of course, more than one view of the crisis in Cuba.

The beginning of 1962 marked the fourth year since the revolutionary government in Cuba had seized power with, in general, popular support. Its popularity began to wane, though certainly did not disappear, as it drifted further towards Communist ideology led by Fidel Castro who, in December 1961, publicly declared himself a Marxist-Leninist and allied the country with the Soviet Union. It is in this context that we should regard accounts of the Cuban perspective written before, during and after those dramatic two weeks in October 1962.

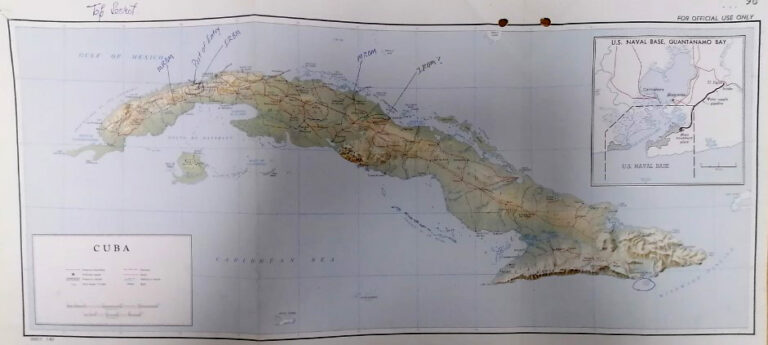

Most Cubans, it would appear, were almost certainly unaware that by August of 1962 the Soviets had begun building military bases on Cuban soil. There was no escaping, however, the Soviet military presence. In a report from the British Ambassador in Havana, Herbert Marchant, just before the crisis, there were ‘signs of considerable uneasiness among the general public as Cubans become aware of the Russian build-up’ (FO 371/162315).

There is a sense of a tense, but far from hysterical, atmosphere among the Cuban people during the crisis itself. In a telegram sent on 25 October, Marchant reported:

‘The people at large still show neither enthusiasm or panic, but there is rather more underlying tension … there has been no frenzied rush on the shops and food supplies still seem to be adequate.’

CO 1031/4226

Then, the following day, just a day before a US U-2 pilot was shot down and killed over Cuba and nuclear war seemed imminent, Marchant wrote:

‘There is still no change in the general atmosphere. Havana remains outwardly calm although markets and food shops are now virtually empty … Committees for defence of the revolution are organising civil defence, but there are still no preparations for a blackout.’

FO 371/162382

Later, looking back on the crisis in his Annual Review for 1962, Marchant dismissed some of the sensationalist foreign press portrayals of Cuba as a frenzied place of zealous revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries, asserting that:

‘for a correct assessment of the Cuban scene the most important feature to keep in mind is not the story of emigré raids on sea front hotels … but rather the fact that the majority of Cubans have for one reason or another got on quietly with the everyday business of living – and they did just this even during the crisis.’

He added: ‘Curiously enough it [the crisis] does not seem to have formed in Cuba so definite a watershed in 1962 as did the failed [Bay of Pigs] invasion in 1961’ (FO 371/168135).

This was all, not that surprisingly, in apparent contrast to Castro’s own experience and view of the dramatic events, and that of at least some of his government.

In a response to a telegram sent to him on 26 October by the Secretary General of the United Nations, pleading with him to order a suspension of the development of the missile launching facilities on Cuban soil, Castro was unequivocal in his determination that without a change in US policy towards Cuba, there would be no Cuban compromise. It is clear he regarded the installation of Soviet missiles in Cuba as a proportionate response to the US naval blockade of the island, which he considered an ‘act of force and war committed by the United States against Cuba’.

As far as Castro was concerned, this was a question of Cuba’s ‘security and sovereignty’, asserting that, unlike the USA in his view, ‘Cuba is victimizing no-one’ (PREM 11/3691). He went on:

‘The revolutionary Government of Cuba would be prepared to accept the compromises that you request as efforts in favour of peace, provided that at the same time, while negotiations are in progress, the United States Government desists from threats and aggressive actions against Cuba, including the naval blockade of our country (…). Cuba can do whatever is asked of it, except undertake to be a victim and to renounce the rights which belong to every sovereign state.’

Khrushchev’s decision, then, to remove Soviet missiles from Cuba was a devastating blow and loss of face for Castro, described by Marchant in his Annual Review as ‘the world’s most public snub to the world’s most publicised primadonna. I myself saw Castro soon after the event. He was sallow, haggard and thin, mentally and physically deflated.’

He added:

‘His stock, as the man who sold his country down the river, is undoubtedly lower than ever before amongst the opposition in this island. But it is equally important to note that we have been able to find virtually no evidence to show that he is to-day, two months after the event, any less popular in the hearts and in the imagination of the young and the faithful.’

FO 371/168135

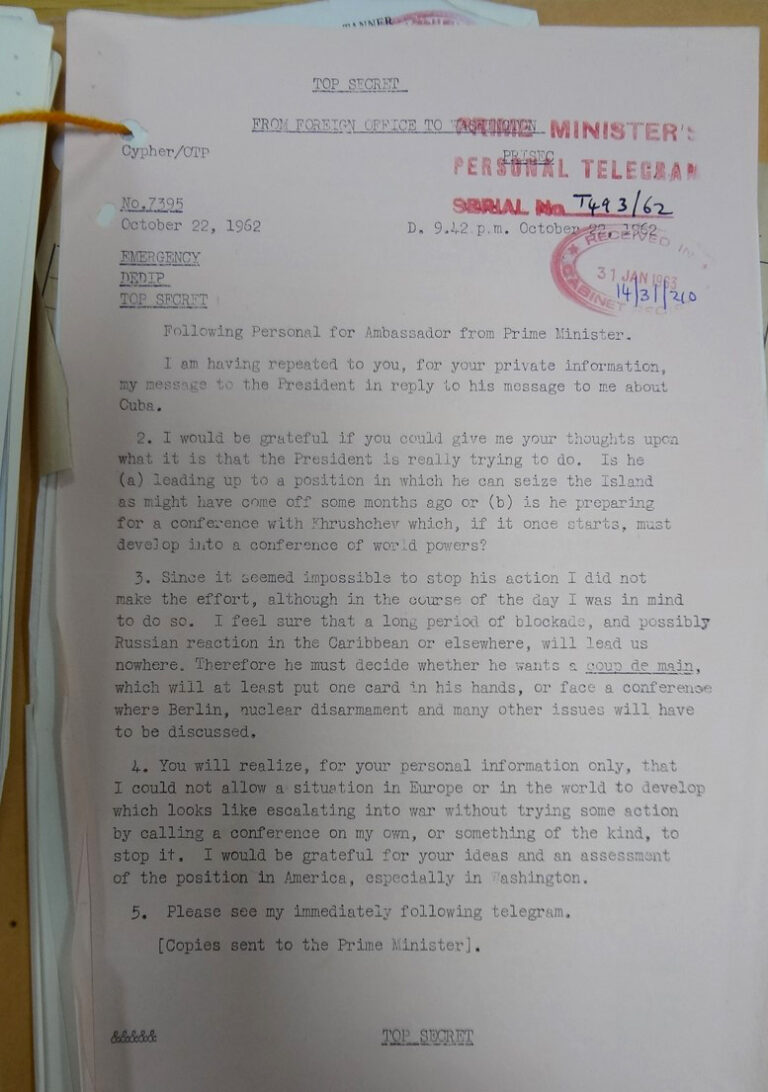

‘What is it that the President is trying to do?’

In Britain, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was unsure as to whether the Americans were just trying to take possession of Cuba, or whether they genuinely welcomed the idea of a conference with the Soviet Union. ‘For the moment the crystal ball remains inevitably clouded’, wrote the British ambassador to Washington, David Ormsby-Gore on 23 October (FO 598/29).

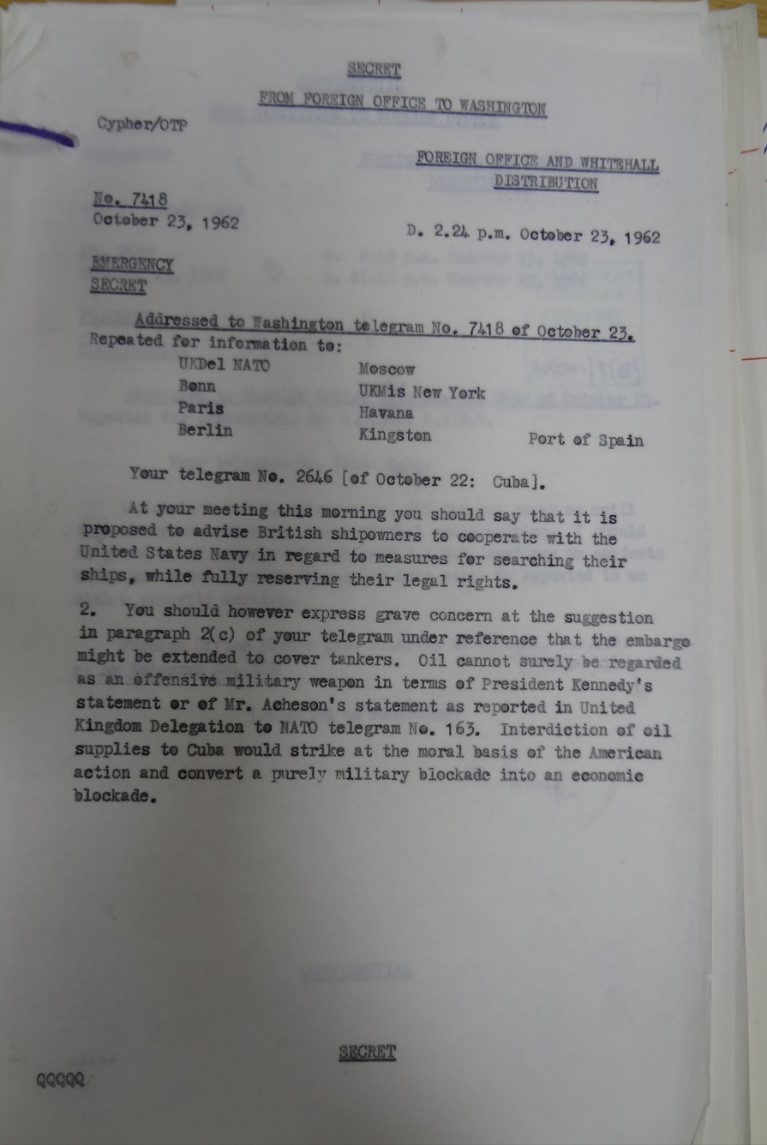

Throughout the crisis, Macmillan, who spoke to Kennedy daily on the telephone, raised concerns. ‘What’s worrying me’, he told the President on 23 October, ‘is how do you see the way out of this. What are you going to do with the blockade? Are you going to occupy Cuba and have done with it or is it going to just drag on?’ He was also somewhat alarmed at the suggestion the embargo may be extended to tankers, which would turn a purely military blockade into an economic one (PREM 11/3689).

The prime minister recognised that the issue was, at the time, one for the USA and the USSR to resolve. However, if the dispute escalated further and extended to Europe, he was prepared to insist that both Britain and France should be included in political and military planning.

Addressing Parliament on 22 October, Macmillan stressed how important it was not to panic. British forces were alerted, but he was ‘adamant that he did not consider the time to be appropriate for any overt preparatory steps such as mobilisation’ (DEFE 13/482).

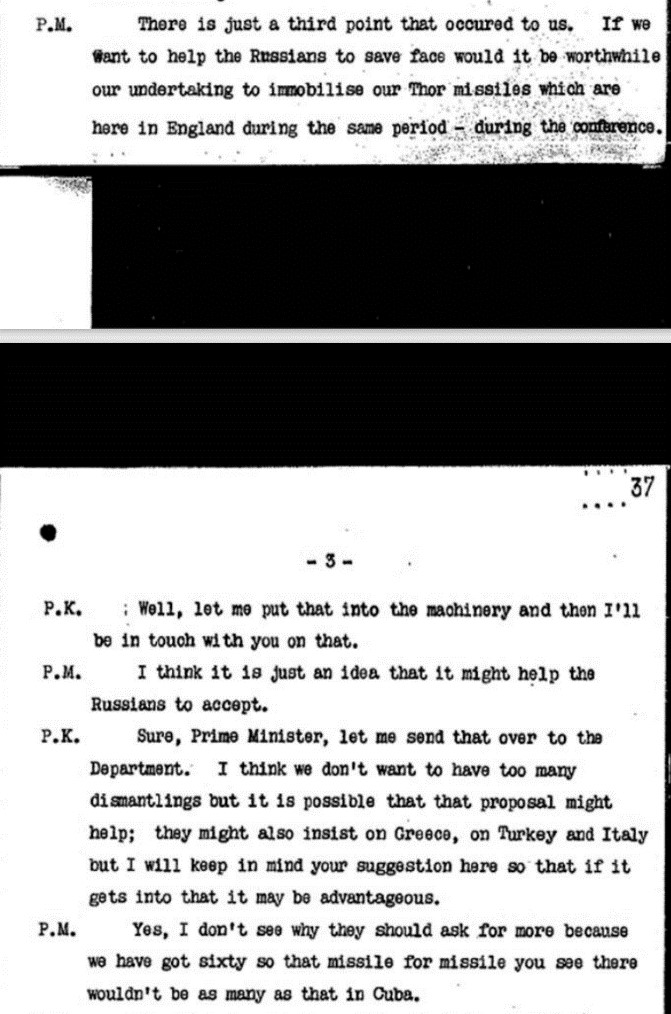

Yet the presence on British soil of American Thor missiles put the country in a delicate position. Alec Douglas-Home, the Foreign Secretary, met with the Soviet chargé d’affaires on 25 October. ‘Mr Loginov said that there were weapons in the UK directed against the Soviet Union’, which sounded like a hardly-veiled threat. ‘I said that there were,’ the Foreign Secretary reported, just as there were Soviet weapons directed against us’ (PREM 11/3690).

Kennedy and Macmillan agreed that if talks were to be held with the Soviets, the missile sites in Cuba had to be dismantled first. As a gesture of goodwill, to ‘help the Russians save face’, Macmillan was prepared to immobilise his 60 Thor missiles (more than the estimated 30 Soviet missiles in Cuba). Kennedy wasn’t very enthusiastic, as the Soviets could then ask for missiles in Turkey, Greece and Italy to be disarmed as well (PREM 11/3690).

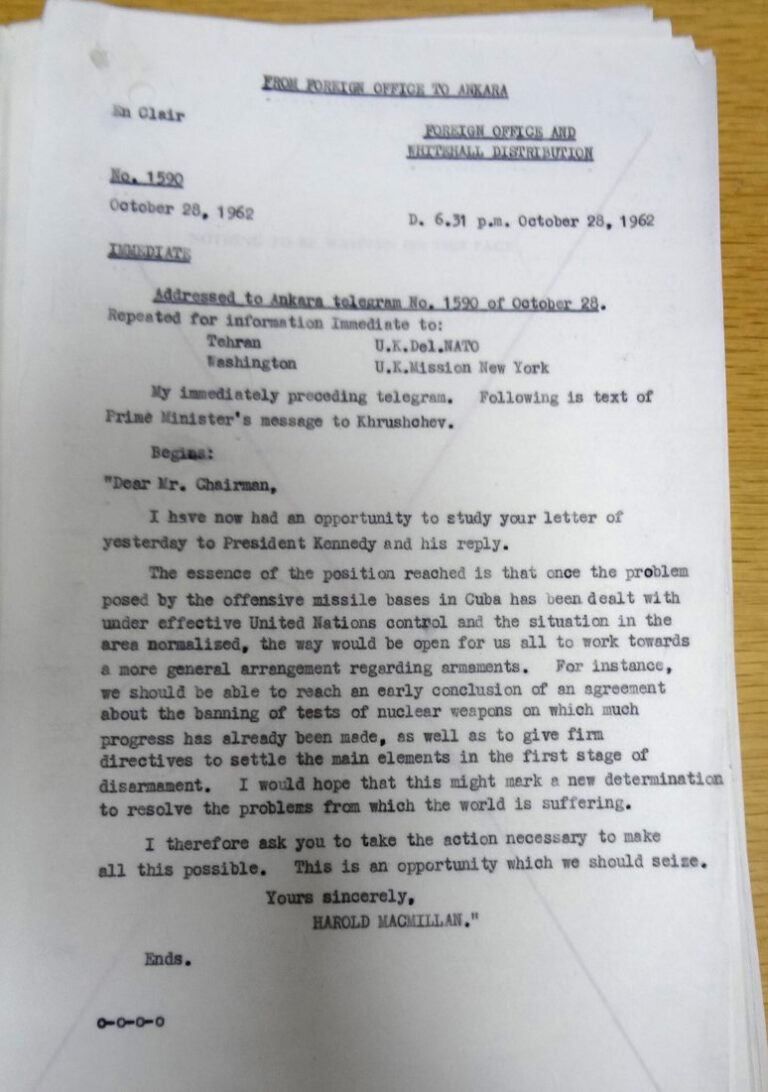

Macmillan never put himself forward as a mediator between the USA and the USSR. He supported the American position that ‘no discussion could take place until the missiles had been withdrawn’. On 28 October, Macmillan wrote to Khrushchev positioning himself as a staunch American ally, but nevertheless a moderate voice, looking for long-term solutions. His message, unfortunately, was received ‘just as Khrushchev’s latest message to Kennedy was being broadcast as a special announcement’ (PREM 11/3691).

At a Cabinet meeting on 29 October, Macmillan commented: ‘in fact we had played an active and helpful part in bringing matters to their present conclusion, but in public little had been said and the impression had been created that we had been playing a purely passive role’ (CAB 128/36/63)

‘Our daily conversations have been of inestimable value in these past days,’ Kennedy told Macmillan on 28 October, acknowledging the advice and support Britain had provided throughout the crisis. Macmillan could breathe, and everyone, including perhaps museum directors, as we will show next, could stop preparing for Armageddon (PREM 11/3691).

‘We won’t let the National Gallery be incinerated’

In 1960, the National Gallery wrote to Treasury, asking for £400 for a ‘dress rehearsal’ of a plan to evacuate works of art in case of a nuclear attack. The plan was ‘to pack up some pictures not at present on display in Trafalgar Square and send them up by rail to Manod’ – a slate quarry in North Wales, where the paintings had been hidden during the Second World War (T 227/2038).

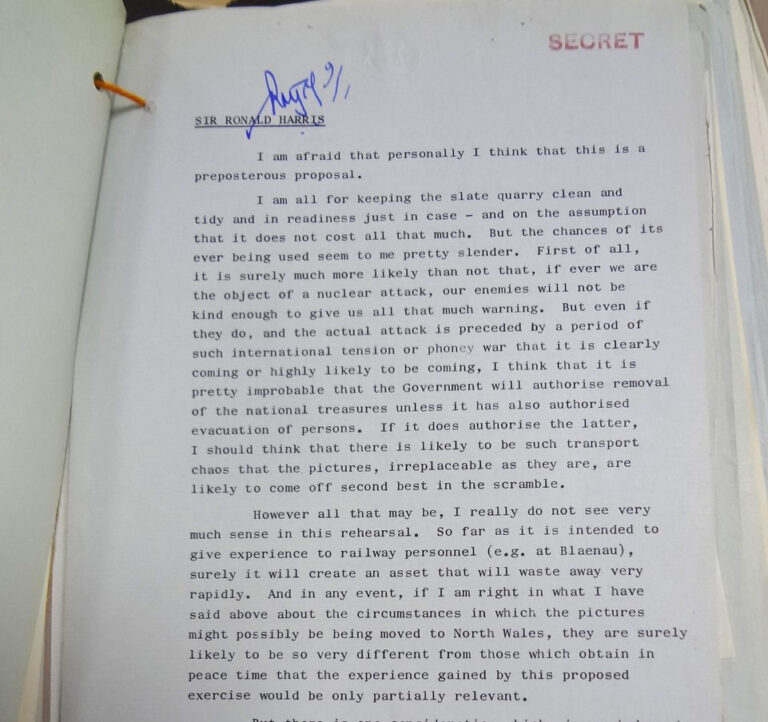

At Treasury, Thomas Padmore thought it was a ‘preposterous proposal’. ‘If ever we are the subject of a nuclear attack,’ he wrote, ‘our enemies will not be kind enough to give us all that much warning’. And if they did, surely the evacuation of people would take precedence, and with it would come ‘such transport chaos that the pictures, irreplaceable as they are, are likely to come off second best in the scramble’. Nothing should be done about it, he concluded, until Ministers had decided what the policy on evacuation should be. He added:

‘There would be a fine opening for criticism on the line that the Government was doing absolutely nothing to safeguard millions of human lives but had prepared, indeed perfected (including a rehearsal) arrangements to safeguard these valuable but nevertheless inanimate objects.’

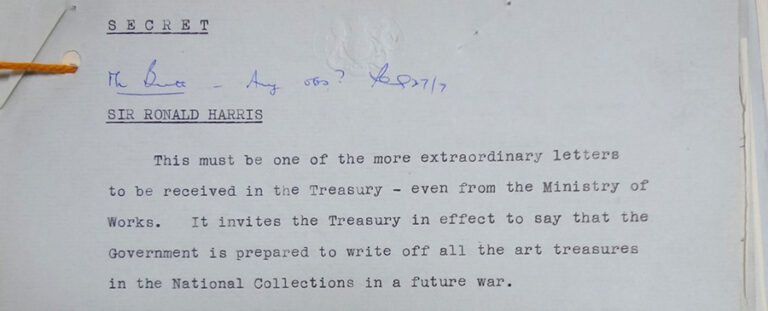

In July 1961, the Ministry of Works changed its earmarking policy – assurance of transport and storage would from then on only be granted ‘on an “essential for national survival” basis’, which, for them, rather ruled out museums and galleries. Writing to the Treasury, it outlined its position clearly:

‘We must ask you, as the Department responsible for the art treasures themselves, to say whether you do in fact wish us and the Ministry of Transport to ty to make plans for their safety or whether you are now prepared to write them off.’

This is when Treasury changed their mind. We won’t ‘let the National Gallery be incinerated,’ they wrote, ‘when civilisation is restored in two or three generations, lost lives will be forgotten but works of art will not’.

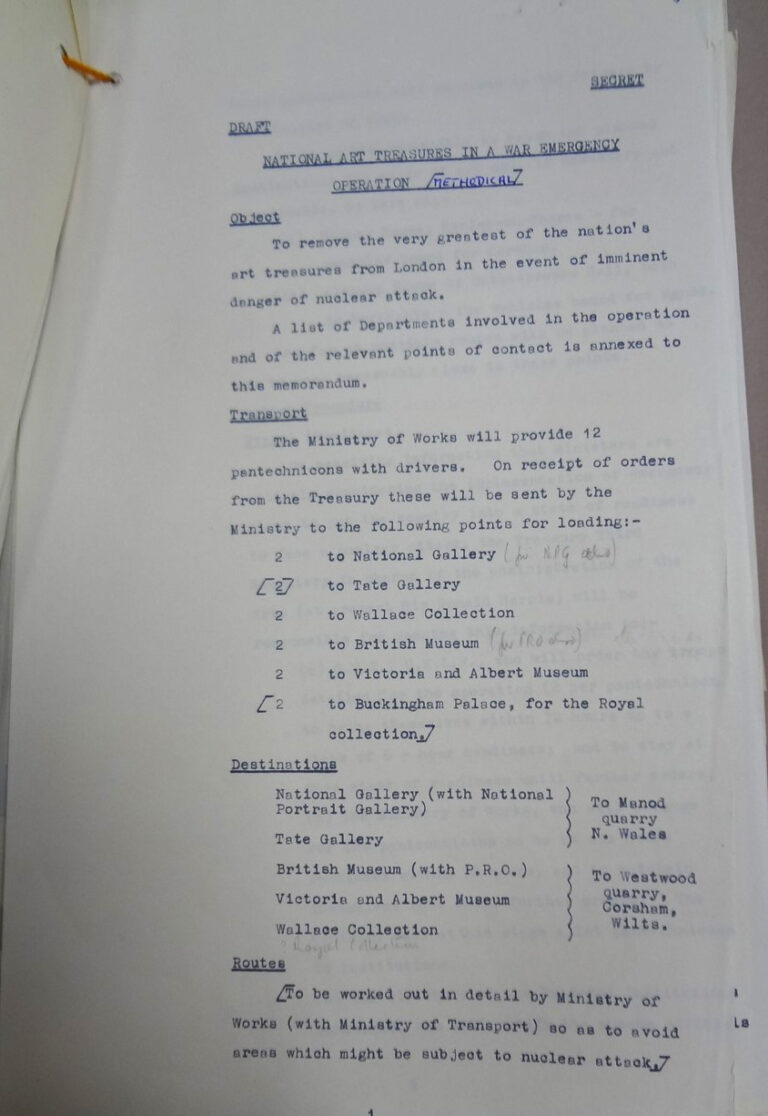

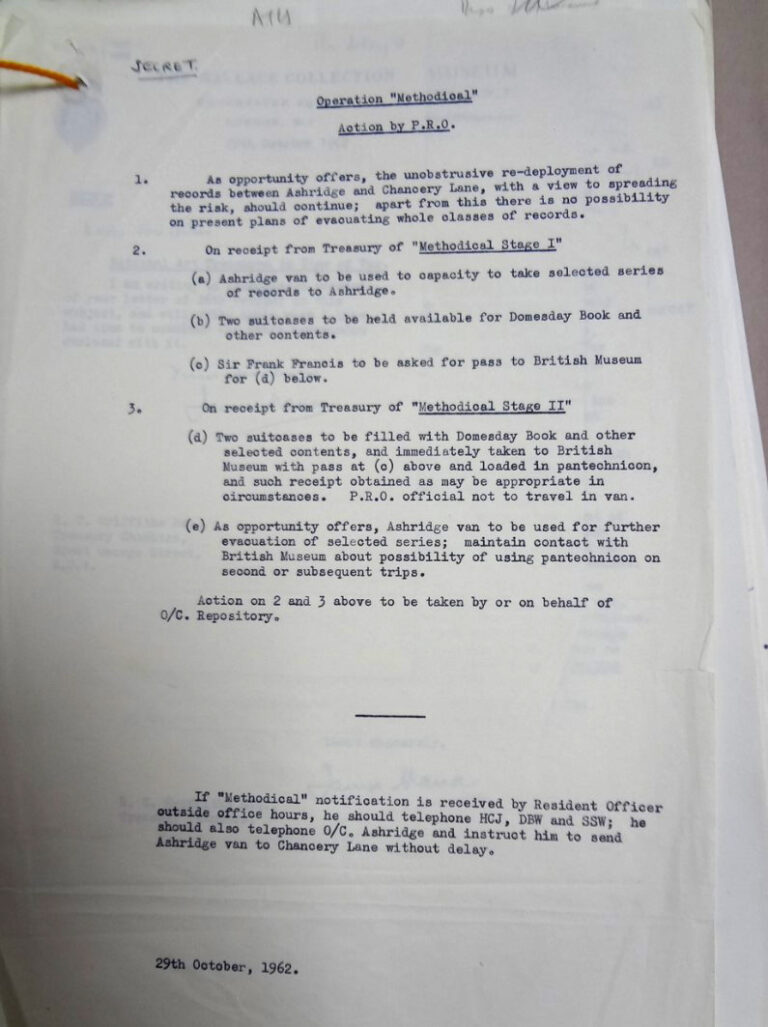

Thomas Padmore didn’t change his mind, but accepted the fact that most people would actually care. This kick-started Operation Goya, later renamed Operation Methodical. In November 1961, an inter-departmental group met up with the directors of the five museums from which objects would be evacuated: the National Gallery, the Tate Gallery, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Wallace Collection, ‘together with the Keeper of Public Records who has one or two vitally important things in his custody (e.g. Doomsday Book [sic])’.

By the time the Cuban Missile Crisis started in October 1962, there was a draft plan. It had to be reviewed as it hadn’t been included in Exercise Felstead (designed to check how long it would take to be ready for war). On 26 October 1962, as the prospect of a nuclear attack seemed less and less remote, the plan was shared with the museum directors. Twelve vans, each with a driver and two UKLF troops, would be dispatched to the museums and Buckingham Palace. The objects, which would have been selected by the directors, would be driven to Manod quarry, in North Wales, and Westwood quarry, in Wiltshire. There would be ‘safe houses’ half-way through. The Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, Anthony Blunt, was kept informed of all developments. Two years later, he confessed to being a Soviet spy.

On 29 October, as Khrushchev had just climbed down, the Public Records Office shared its own plans: it would send two suitcases full of documents to the British Museum, who would make space for them in one of their vans. Sadly, the plan does not reveal which of our iconic document would have been saved!

Methodical was never implemented. Still, the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the Cold War closer to home than many would have liked. As Kennedy told Macmillan on 22 October 1962, it was ‘a solemn moment (…) for the fate of the entire world’.

Fascinating as always.

As a young child I can’t honestly say I knew anything about the crisis but as I went to work in the early 1970s in a central government ministry it was part of life – not a huge thing but always there.

I remember asking a middle-ranking military officer if we could actually do anything to the Soviet forces and their Warsaw Pact allies if they decided to invade West Germany.

‘No,’ he said, ‘but we’d make their eyes water.’

Years later talking to work colleagues 10 or more years younger, I was struck by the fact that the possibility of nuclear war and the terrorism of the 1970s – something I had grown up with as a child and young adult – had such a huge effect on them, creating real fear.