When one considers the formal conclusion of the war against Japan 75 years ago, within the popular imagination two separate horrifying visions spring to mind, visions that have come to epitomise the manner in which the conflict in the Far East came to a close.

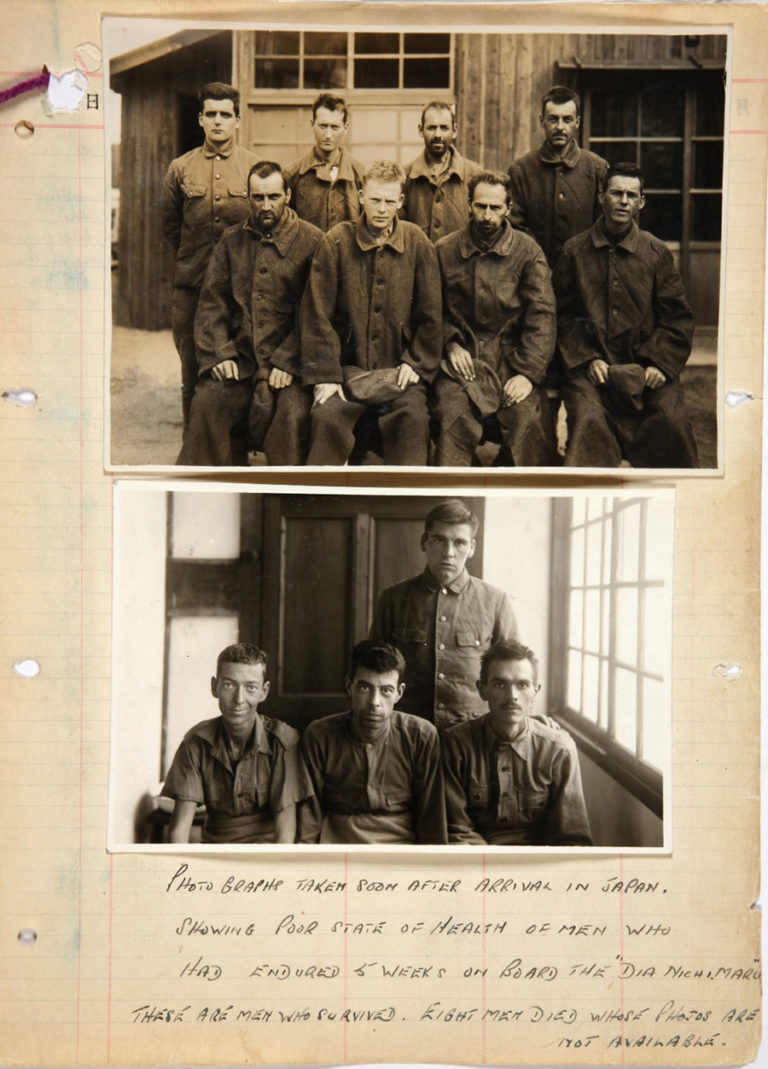

The first is of the atomic blasts which obliterated the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, wreaking untold devastation on the cities’ civilian populations, and leaving a terrifying legacy in their wake. The second is of the starving, emaciated and haunted-looking British and Allied prisoners of war who were liberated from three and half years of slavery and malnourishment. Few would associate both within the same setting.

However, so it was for many hundreds of Allied POWs who were incarcerated in labour camps dotted around the outskirts of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki metropolitan areas. The National Archives hold photographs and handwritten accounts, specifically within AIR 49/384, which detail the conditions at one of these POW camps, Hiroshima Camp No. 2 on Innoshima Island, along with medical care afforded to its inmates. In addition, within ADM 223/168 is an extraordinary eyewitness account of the atomic explosion that destroyed Nagasaki, while ADM 1/17343 contains a very brief account of the two-man British medical mission which provided medical care to British POWs prior to their evacuation from the Nagasaki area.

Innoshima POW Camp at Hiroshima

According to the report drafted by Warrant Officer Fabel of the Army Education Corps, who arrived at the Innoshima Island POW camp from Hong Kong on 23 January 1943, he had found some 92 POWs already interned there. This included one Lieutenant-Commander of the Royal Navy, four officers and two Warrant Officers (WOs) of the RAF, along with around 85 RAF servicemen of ordinary rank. To this number, Fabel’s recently-arrived detachment added 100 prisoners, including 86 members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC), a formation of mainly white British and Commonwealth civilian militiamen who were mustered to defend the colony from attack (AIR 49/384).

The Innoshima camp included two-recently constructed barrack buildings which faced out onto the Inland Sea and the adjoining Mitsubishi dockyard. From the account, it appeared that prisoners at this camp were accommodated relatively well in one of these buildings, which had seven double-tiered rooms, each holding 32 rice-straw pallet beds in wooden frames, called ‘tatamis’, with 16 on the ground floor and 16 in two galleries above. Each prisoner was given five blankets and officers and WOs were given straw mattresses for their beds. Fires in stoves were provided from December to March, while mosquito nets were allocated throughout May to September. Two rooms in a separate building were allocated for use as a hospital, and could accommodate up to twenty cases (AIR 49/384).

However, in spite of the apparently good conditions, all was not well for the inmates of Innoshima Camp. The conditions of work were tough, and food rations were not abundant. The majority of those hospitalised during their incarceration suffered from malnourishment, while others sustained severe injuries. The camp lacked a British medical officer, which was a major drawback as the word of such a figure could have proved key in saving sick and injured POWs from work. Instead, they received occasional visits from a Japanese medical officer and were fortunate to have the Habu Dockyard Hospital staff to call upon when necessary (AIR 49/384).

The Habu Dockyard was owned and run by the Osaka Iron Works Company. It was for this organisation that the inmates of Innoshima Camp, under the direction of Lieutenant (later Captain) Nomoto and his administrative staff, would labour from 1943. Fabel’s report would contain a detailed appraisal of all the medical treatment afforded to the prisoners of Innoshima, along with lists of medical supplies maintained, details of International Red Cross aid delivered to the camp, together with signed witness statements taken from POWs who sustained injuries during their time working at the dockyard (AIR 49/384).

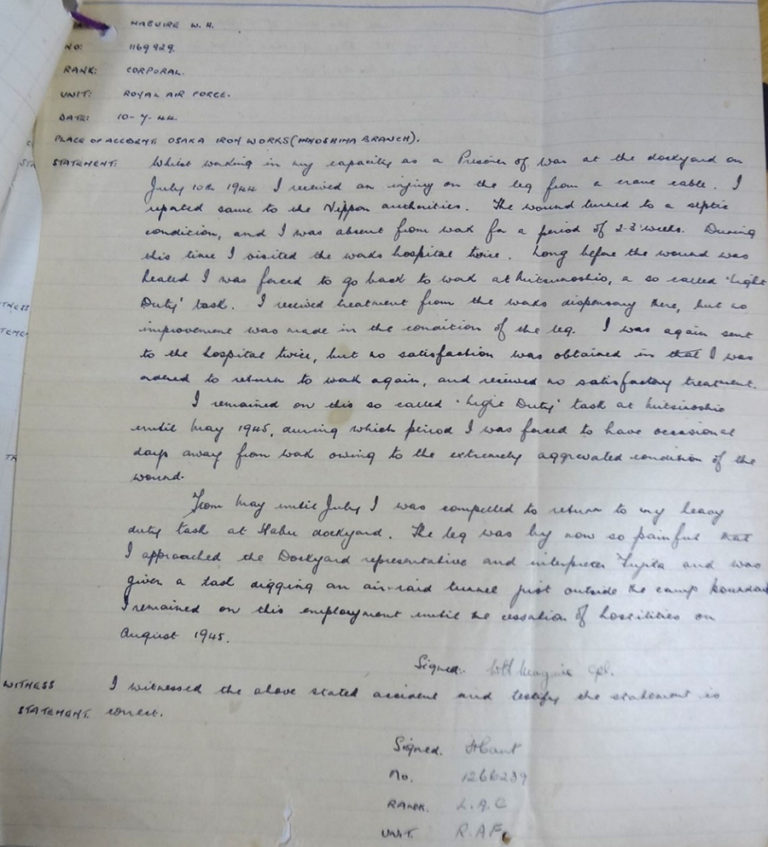

Leading Aircraftman (LAC) Maguire’s witness statement delivers a perfect example of the sufferings of injured POWs who were forced to continue working in spite of their wounds. Maguire received a wound to his leg from a crane cable at the Habu Dockyard on 10 July 1944, and the wound soon became septic. He was absent from work for 2-3 weeks, during which time he was twice able to visit the dockyard hospital. However, before the wound had healed he was sent to work carrying out so-called ‘light duty’ tasks at the Mitsubishi Dockyard near the camp. Although he received treatment from the dockyard dispensary, the condition of his leg did not improve, and despite two further visits to hospital, Maguire ‘received no satisfactory treatment’ (AIR 49/384).

Maguire would remain on ‘light duty’ tasks at the Mitsubishi dockyard until May 1945, by which time the severity of his leg wound had become increasingly aggravated. He was then compelled to return to his ‘heavy duty task’ at the Habu Dockyard, but the pain of his wound forced him to appeal to a dockyard representative through an interpreter named Fujita. Maguire was, instead, set to work digging an air raid tunnel just outside the camp. He would remain at this task until hostilities ceased in August 1945 (AIR 49/384).

A British POW eyewitness to the Nagasaki atomic blast

Inevitably, many British and Allied POWs imprisoned in camps on the outskirts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki became eyewitnesses to the atomic explosions which obliterated both cities. One eyewitness account of the Nagasaki blast was circulated in a Weekly Intelligence Report produced by the Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division in November 1945. The source of the account was a Petty Officer of HMS Exeter who had been a prisoner at Fukuoka Camp No. 11, four miles away from the blast epicentre (ADM 223/168).

The POW eyewitness was working alongside fellow prisoners, gardening on a hillside with a ‘ringside view’ of where the bomb exploded. At 10:58 hours on the morning of 9 August (erroneously recorded as 2 August) they watched a B 29 aircraft drop three parachutes over the target area, one large and two small. The larger parachute detonated 100 feet from the ground, emitting a blinding flash which, according to the eyewitness, ‘would have lit up the whole of England had it been dark instead of daylight’. The flash was so brilliant that it appeared to blot out the sun, and the heat emitted so intense that it held the eyes open for eight seconds, giving the eyewitness ‘the impression of being dangled in hell and hauled out’ (ADM 223/168).

According to the account, it took 22 seconds for the shockwave from the blast to reach the hillside where the POWs worked. They watched as four square miles of factories and houses went into the air and came down as dust and molten metal. Later they discovered that railway engines, a mile from the explosion and weighing 100 tonnes, were lifted from their rails and thrown 300 yards. In addition, the Mitsubishi steel works, one of the largest and most prominent manufacturing plants in the city, was razed to the ground and its metal superstructure melted in the heat. However, it is the description of the gigantic white cloud left behind by the explosion that proves to be the most terrifying aspect of this account (ADM 223/168):

‘About four minutes after the explosion a dense white cloud appeared over the target, a man-made cloud of terrific density, so dense that smoke from thousands of fires created by the bomb could not penetrate it, but arose in huge columns in outer extremities of this pure white cloud.

A little later, looking through a pair of common sun-glasses at the cloud, colours appeared that I have never seen before; it looked like a giant catherine wheel, only very slowly revolving and milling, green merging into purple and reappearing as blue as Arctic ice pack, only to disappear and reappear as blood red’ (ADM 223/168).

The British medical mission and the evacuation of POWs from Nagasaki

On 8 September 1945, six days after the formal surrender of the Imperial Japanese government aboard the USS Missouri in Yokohama Harbour, two Royal Navy Surgeon Lieutenants named Cotsell and Cardew disembarked at Yokohama from HMS Indefatigable. They would spend 20 days in Japan; their mission was to provide medical attention to repatriated POWs and oversee their safe evacuation from the country. Much of their activities would be carried out at Nagasaki harbour where thousands of former Allied POWs, most of them British, were brought for processing, medical examination and treatment, followed by embarkation (ADM 1/17343).

The two Royal Naval medical officers worked alongside colleagues in the United States armed forces under the direction of Colonel Griffin of the US Army and Captain Parsons, the Principal Medical Officer of the US Navy Hospital Ship Haven. From 14th to 17th September, they worked with American medical officers to process trainloads of former POWs, numbering on average between 600 and 1,000, which passed through daily. The reception of these POWs, as Cotsell and Cardew observed in their report, was most efficient, and British servicemen were ‘pleased’ to see the Royal Navy uniforms among the host of American uniforms which greeted them upon arrival. In addition, each train which rolled into the station was met by a brass band playing the appropriate tunes: ‘for the benefit of the British lads, “Tipperary”’ (ADM 1/17343).

Stretcher cases, skipping the normal procedure, went straight aboard the USS Haven, while walking cases were given coffee and doughnuts as clerical staff filled out both Army and medical forms. Once processed, each case was put through a shower and sprayed with D.D.T. (for malaria and typhus), before being issued with a new set of clothes and ‘toilet gear’. After 18 September, Captain Parsons suggested that Cotsell and Cardew should work on the 80-bed ward on board the Haven, a proposal accepted by both officer. They would remain at this post until their departure from Nagasaki on 23 September (ADM 1/17343).

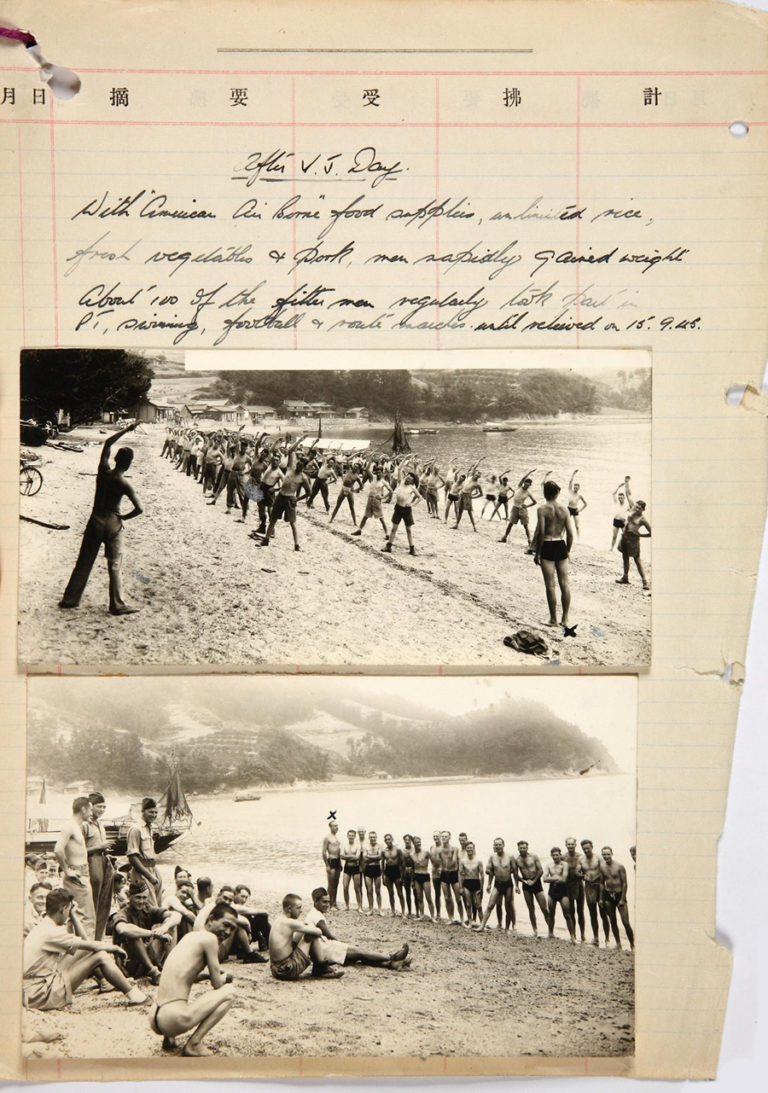

During their period on the hospital ship, they learned that 30 per cent of the ex-prisoners who arrived at Nagasaki had been admitted to the Haven, suffering mainly from malnutrition and avitaminosis (severe vitamin deficiency). This was remedied through ‘a balanced diet and large doses of vitamins’, administered either orally or parenterally. Thiamine, administered by injection, was discovered to be especially effective in the treatment of both malnutrition and Beri Beri (ADM 1/17343).

Cotsell and Cardew also reported that a great number of cases admitted to Haven were prisoners suffering from tachycardia (accelerated heart rate, exceeding the normal resting rate), which was identified by both officers as possibly resulting from overindulgence in caffeine and nicotine; the majority of prisoners had undergone a sustained abstinence from both substances for more than three years. There was one death among all the cases admitted to USS Haven. This former POW suffered a cardiac arrest and died after overeating following a severe case of Beri Beri (ADM 1/17343).

This death, along with the nature of many of the cases admitted to the Haven, underlines the poor state of health in which many of these former prisoners were found by Allied medical staff at Nagasaki port. This, invariably, points to a prolonged period of abuse and maltreatment at the hands of their captors. The choice of Nagasaki as one of the main ports for the processing of repatriated Allied POWs, in view of devastation recently inflicted upon the city, whether by accident or design, is somewhat symbolic of the two tragedies which came to mark the end of the war against Japan. A shattered city which became a place of healing for shattered men.

Thank you for posting this I will read it thoroughly.

I always scan the photos just in case my father is in one. Up to now he hasn’t but ….

Very interesting reading. I have been researching the story of Capt. Reg Newton, 2/19th Bn, AIF, who was at at Hiroshima PW Camp 9B Ohama along with Ray Parkin, author of ‘The Sword and the Blossom’, as I’m sure you’d know. The description of the bomb blast on Nagasaki is very powerful.

Sorry. I’m back again. I was just updating some of my own records with some of the information here and saw the reference to the interpreter, Fujita, at Innoshima but then that led me to this information about him (which you probably know but if not may be of interest):

Fujita Mitsuyoshi, Civilian Interpreter. Tried in Sept 47 and sentenced to six months’ prison.

The information I saw from the Monthly Reports to Supreme Command in Japan states:

Was also “Timekeeper”. Was at 5th Branch POW Camp, also known as Innoshima POW Camp, Hiroshima Area btw 42 and 45.’

Besides curing and looking after the rescued POWs, I would like to ask you to disclose relevant archives how the British occupied army contributed to reform the local society in West Japan, cooperating with the US commander in chief, Douglass McCarthur, especially landlord system, and educational system, during the occupation period.

Are there any photos of returning P O W s with Jack Dempsey

I only found this page because i was looking for info on the prisoner of war camp near Nagasaki during WW2. Last week i met a man who was on a US destroyer that was sent to Nagasaki after the surrender of Japan to pick up the freed prisoners of war. He told me he got off the ship and saw the city flattened. I didn’t get to ask a lot more about that since i didn’t want to bug him. But i was impressed. He’s a roofing contractor, keeping busy. He went up two ladders into two roofs with me, at 96 years old. His name is Joe. I was amazed.

Wow we’re sure one of the men on the photo showing the group of men sitting on the beach is my grandad Harry Ramshaw. He was liberated from Nagasaki. Amazing – I can’t think of how we would get evidence but we’re convinced.

My uncle and namesake Squadron Leader Donald Moulden was starved to death in a British POW camp very near Nagasaki and was the last person to die in the camp on August 19th 1944.

His body now lays in the Sydney War Cemetery.

I can’t seem to find out which camp he was in. Where could I find out please?

H i there My name is John Leaver and my father Lance Corporal William Frederick Leaver was a POW of the Japanese from March 1942 (in Java) until liberation from Camp Ikuno near Osaka on the 9th September 1945. About two years ago my niece and I researched and wrote his life story including an extensive passage about his days in captivity. From our research we were able to piece together most of his ‘journey’ but a couple of missing pieces of information were how he got from Camp Ikuno to the port from which he was shipped to Manila before his journey to Canada on the HMS Implacable. In his liberation statement Dad said that on route he saw the devastation caused by the Atom Bomb in Hiroshima and that he was shipped from Japan to Manila on an American destroyer did not name it.Can you help?

I have a small number of pictures my father Lionel Beattie 619535 Airman 1st Class

brought back with him from Japan. He was captured in Java and travelled via a Japanese ship as a British POW to Japan. He spent 3 and a half years in Japan working in coal mines. The last camp he was in before liberation I believe was:-

Hiroshima 6D – Motoyama (later 8B)

My Uncle was Private F Pay 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment. In all the years after Liberation I was the only person to whom he talked about his experiences and then only once. This research has allowed me to put some bones on his experiences which is allowing me slowly to build knowledge of what he went through. From the way he talked the fact that the Guards on that fateful day near Nagasaki allowed them to use their air raid shelter meant that he started building tge strength to forgive. Always a fit sportsman (trials to play football and cricket at a professional level pre war) who said growing up in poverty meant he was better prepared for the deprivation of the camps I cannot help but wonder if he is one of the men on the beach.

For anyone who may want to visit them I recently visited Nagasaki and Hiroshima and found two memorials to Allied PoWs who died in the atomic blasts in each of the cities. One, in Hiroshima, was to 12 US PoWs, all originally survivors of the aircraft the Lonesome Lady and the Taloa both of which crashed in Japan who were incarcerated at the Chugoku Military Police HQ. The memorial is located on an alley at the rear of the Sumii Clinic on Kamiya-cho East. The other is a monument in the Nagasaki Peace Park dedicated to the memory of those from Nagasaki Camp Fukuoka 14b, an information plaque about which can be found under a flyover on the north side of Inasa Bridge Street on the east side of Inasa Bridge.

Anyone out there who knew my father Simpson Third who was taken to Nagasaki POW from Burma Love to know all about their time there and journey back to Britain

Reference “How the British occupied army contributed to reform the local society in West Japan”

In the early 1980s, I had a working lunch with an ex-British Army Colonel (on unrelated business). He had been a young officer on the staff of the British occupying force, in Japan, immediately after WWII. He told me that the Japanese desperately wanted to be rid of the occupiers and understood that the way to expedite this was to cooperate. He said there was no trouble and he admitted that a lot of his time, there, was spent hunting and fishing!

Used to drink with a man who was POW in nagasaki, he was in a mine when the bomb was dropped, told me they got in the cage to come up, it rose 10 feet there was a big rumble and it fell to the floor, eventually they got out of the mine but couldn’t understand where all the Japanese had gone, the devastation was much worse then the photos, the sea was boiling and ships had melted in the harbour, I asked if it was the right thing to do he said “of course if they’d invaded the POW’s would of all been killed out of hand”. He passed away only a few years ago.

I am a 97 year old veteran who was part of the crew of the U.S.S. Chenango CVE 28 An air craft carrier, along with a hospital ship USS Hay-vin. We evacuated the prisoners, and got them back to their start to freedom. Our flight deck , hanger deck, and any place a cot would fit. we took them. In my 97 years I have never forgot the gratitude I felt.Just to be a part of that. I did talk with some of the prisoners . I estimate we may have taken a thousand men off of that hell hole. This evacuation was one month after he bomb.

I did get to take a drive on a truck along with maybe ten more men to see what an atomic bomb could do. It isn’t anything I can , or want to try to explain.

My Father, Bill Burns ( Koown as Red Burns because of his socialist beliefs) was a prisoner at Funatsu prison camp. He died aged 59 of lukaemia. My mother also died of lukaemia. Is there any research into deaths from Lukaemia among the prisoners who were in the area where the bomb was dropped? My father’s GP told me that there is little doubt that my father’s death was associated with his exposure to the nuclear bomb.

My dad was Edwin Clarke and he died in a Japanese camp of disentery. He was catured in Java and was in the Royal Artillery. Can anyone remember him, as I would like to know the full story. I was 8 years old when he died, and still at88 remember giving my mum the telegram.

My uncle Australian Soldier Signalman Javis “Jim “Whitley was a prisoner of WW 2 captured in Singapore, and taken to Nagasaki where he worked in a coal mine for three and a half years apparently owned by thec Kawaski Company. Does anyone know much about the Australian Soldiers there ?

Thank you for posting this article. The Education Corps Warrant Officer at Innoshima was my grandfather, F.A. Fabel (not “Yabel”). I would also like to note that a book entitled, Living with Japanese, describes life in the camp.

For Gillian Friel, my grandad who was at a pow camp near to the bomb, also died at 59 but from stomach cancer.

My Husband Ernest Edwin Charles Jenner was a Tailend Charley for the Brits. The narative on the bomb that was dropped in Nagasaki is totally correct as Ernie explained it to me. He passed away at age 52 from Cancer which invaded his Thorasic region and eventually his brain. Thank you for saving the pics and the information.

Thank you for this blog and putting it all together. If you have any pictures of Ernest Edwin Charles Jenner (service # 900585) (camp# 6363), it would mean a lot to my mother and his daughters-me being one of them.

https://www.britain-at-war.org.uk/ may provide some with details of where relatives were held captive and where they passed away under the Japanese.

Are there any photos with Edgar Glover in Nagasaki. POW camp a mile from Fat Boy epicenter 9th August 1945,he survived a rest day

He lived on l lived in his house with my mother his daughter and three uncles one is still alive today

I’ve just read my great uncle Owen Mahoney’s book about his time as a Japanese POW and how he saw the atomic bomb too. I am searching for any photos that might have him in it. I can’t believe what they all went through during their time there. Remember them❤️

This is a message for Sarah Vialan: I am a journalist interested in people who witnessed the atomic bombs in Japan. I would like to talk to you about your great uncle Owen Mahoney and his book. If you would be interested I hope you will get in touch with me at: jason@tbsnews.co.uk

This is a message for Beryl Taylor nee Jenner and Naomi Jenner.

– Your dear E.E.Ch. Jenner is listed in a book by Dr. J Stellingwerff (1980): Fat Man in Nagasaki ; Nederlandse krijgsgevangenen overleefden de atoombom (Dutch language only).

– How 212 POW’s (including E.E.Ch. Jenner) arrived in Fukuoka 14 camp (in Nagasaki) on June 25th 1944, has been written on pages 43 tot 52 (in Dutch language only).

I am looking for any information on a POW with the surname GRUMMITT. He was captured during the first wave. He survived the camp. The information is for our family tree folder.

I am his great niece

Many thanks

Dear Caroline,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to family history, please use our live chat or online form.

We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

This is a message for Carol Griffiths:

You have good reasons to be convinced that your granddad Harry Ramshaw is in the picture on the beach near Nagasaki. But I cannot confirm your opinion.

– In 1944, on December 3d: the last 4 POW (all British) arrived in camp Fukuoka 14 . They got the highest camp numbers 541 to 544; three of 4 names are given except nr. 542 (re.: Dr. J. Stellingwerff, 1980; most POW in Fuk14 were Dutch).

– Another source proves that POW number 542 is GB Army Corporal Harry Ramshaw. He is a survivor of FUK-14, as you know. His full home address in the UK is copied in FUK-14 Rosters 1946-02-16. You may find these data via http://www.Mansell.com

– If you like to write his testimonial, you may check a new website https://fukuoka14b.org

You may contact a photographer for more support of your opinion. Good luck.

A good friend, sadly no longer with us was POW here at Hiroshima 5.

His name Earnest Syder, born 12/04/1923.

He worked in the kitchens, so was lucky!

My fathers brother was on the Singapore Maru hell ship and then was a POW in Motoyama #8B , I think it actually finished as Hiroshima #8B after being Hiroshima #6D . I have found his name and his photo while researching, quite emotional. I’m going to Japan next year God willing as I am now nearing 80 and I would love to know the exact spot of the camp . He also spoke affectionately about a Ned Kelly a Cockney who finished his days as a Chelsea Pensioner his name is also on the list