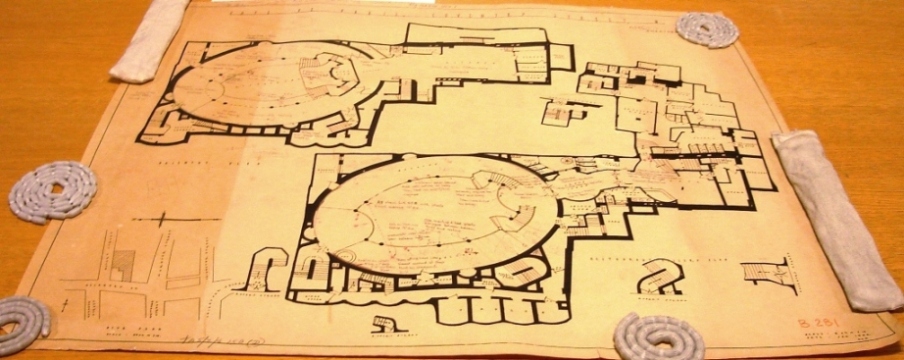

Plan of the Café de Paris, showing the effects of the bombing (reference: HO 193/68). The plan is shown laid out with weights to keep it flat.

Seventy-two years ago, on Saturday 8 March 1941, the Café de Paris, a London nightclub and restaurant was bombed during the Blitz. A 50 kg high-explosive bomb hit the building, on Coventry Street, at about 21.45. At least 34 people died and dozens more were seriously injured. [ref] 1. The National Archives HO 193/25, City of Westminster District, 8/9 March 1941, entry number 5; Westminster City Archives CD/2/5, entry number 1213. [/ref]

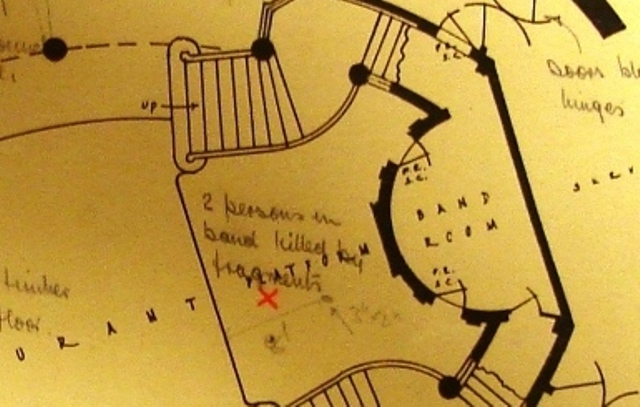

This detail from the plan shows where two members of the band were killed by fragments (reference: HO 193/68).

Before the war, the Café de Paris had been a very exclusive venue, but by 1941 entry prices had lowered and it was popular with a more mixed clientele, including service personnel on leave. [ref] 2. Charles Graves, Champagne and Chandeliers: the Story of the Café de Paris (London, 1958), page 126. [/ref] As it was still relatively early for a Saturday evening, the basement and ground floor areas were only half-full when the bomb fell. If it had struck the building an hour later, the Café would have been much busier and many more people would have died. [ref] 3. Graves, page 120. [/ref]

This was the most devastating incident during a night of heavy bombing. [ref] 4. The National Archives HO 202/3 and HO 203/6, reports for 8/9 March 1941; Westminster City Archives CD/6/129, Appendix A to minutes dated 12 March 1941. [/ref] It was recorded at both central and local levels of government and much of the official paperwork still survives in different archives. For instance, Westminster City Archives holds the local civil defence incident register and situation reports, [ref] 5. Westminster City Archives CD/2/5; CD/2/17. [/ref] the city council’s Emergency Committee minutes, [ref] 6. Westminster City Archives CD/6/129. [/ref] and locally-produced maps. [ref] 7. Westminster City Archives CD/22/142. [/ref] Records at London Metropolitan Archives include the London County Council bomb damage map [ref] 8. London Metropolitan Archives RM/22/61 [/ref] and the London Fire Brigade Department’s situation reports. [ref] 9. London Metropolitan Archives LCC/FB/WAR/LFR/01/023. [/ref]

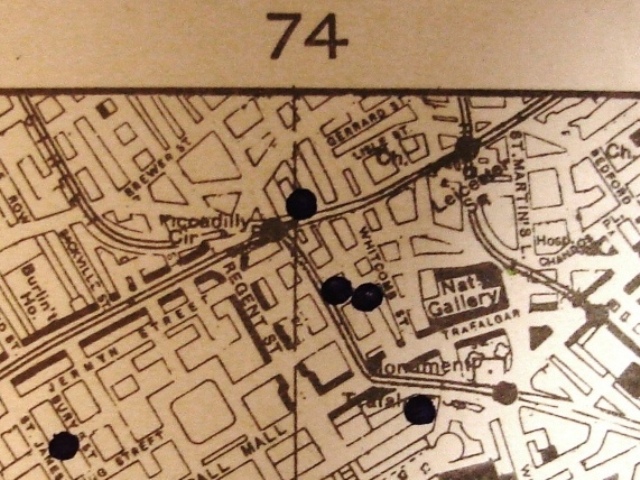

This detail from a Bomb Census map of the area shows bombs that fell during the week of 3-10 March 1941 (reference: HO 193/23, sheet number 56/18 NW).

Here at The National Archives, we have central government records kept by the Ministry of Home Security. Those relating to this incident include the weekly Bomb Census map, and the associated ‘BC4’ reporting form, [ref] 10. The National Archives HO 193/23 sheet 56/18 NW; HO 198/25. [/ref] as well as daily summary reports. [ref] 11. The National Archives HO 202/3; HO 203/6. [/ref] We also hold the detailed plan shown at the top of this post. [ref] 12. The National Archives HO 193/68. [/ref] This plan is annotated in pencil to show the effects of the bomb, both on the structure of the building and on the people inside. The annotations agree with contemporary eyewitness accounts, which noted that while some of the survivors suffered terrible injuries, others escaped unharmed. Even some of the dead bodies were not visibly marked. [ref] 13. Graves, page 119. [/ref]

As with many bombing incidents, newspaper reports about the Café de Paris bomb were limited and rather one-sided. For instance, the report in The Times on the following Monday [ref] 14. The Times, 10 March 1941, page 4. [/ref] was upbeat in tone. It highlighted the bravery shown by survivors and rescuers and made much of the fact that all of the cabaret dancers survived unharmed. In an attempt to prevent the German authorities from learning about the impact of the bombing campaign in detail, the building was not named, being referred to simply as ‘a restaurant’. It was almost a month later that a small article appeared naming the Café de Paris and hinting at the full extent of the casualties. [ref] 15. The Times, 7 April 1941, page 2. [/ref] Similarly, a local newspaper report about recent air raids concentrated on how firewatchers had dealt promptly with lesser incidents. [ref] 16. Westminster and Pimlico News, 12 March 1941, page 3. [/ref]

This image, taken from BombSight.org, shows how heavily this part of London was bombed during the Blitz.

Other sources offer a less positive view about how the incident was handled, particularly with regard to the provision of medical care for injured survivors. Nurses from Charing Cross Hospital ran out of dressings and had to borrow some field dressings from the Scots Guards, who had been called in to stand outside the building. [ref] 17. Philip Gibbs, The Journalist’s London (London, 1952), pages 161-2. [/ref] A Mr Davis complained afterwards to the London Civil Defence Headquarters that too many ambulances had been sent to minor incidents on the same night, leaving too few available for the Café de Paris. However, the results of the ambulance service’s investigation suggested that his criticism was unfounded. [ref] 18. LondonMetropolitan Archives LCC/PH/WAR/03/017. [/ref]

The Café de Paris remained closed for the rest of the war but reopened in 1948. [ref] 19. ‘History’, Café de Paris corporate website. [/ref] It is still open today.

Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson, dance band leader

Perhaps the best-known victim of the Café de Paris bombing was the musician Kenrick Johnson. Ken was born in what was then the colony of British Guiana (now known as Guyana) in 1914. [ref] 20. Val Wilmer, ‘Johnson, Kenrick Reginald Hijmans (1914-1941)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004; online edition May 2006). [/ref] He came to the UK aged 14 because his parents, who had hoped that he would become a doctor, wanted him to have a British education. The passenger list for the SS Nickerie shows that he travelled alone, arriving at Plymouth on 31 August 1929. [ref] 21. The National Archives BT 26/910/42. [/ref]

Ken was more interested in music and dance than in medicine. After leaving school, he became a professional swing musician and was given the nickname Snakehips. As the band leader of the West Indian Dance Orchestra, he performed regularly at fashionable London venues, including the Café de Paris. At the time of his death, he was 26 years old, and at the height of his career. [ref] 22. Wilmer, op cit. [/ref]

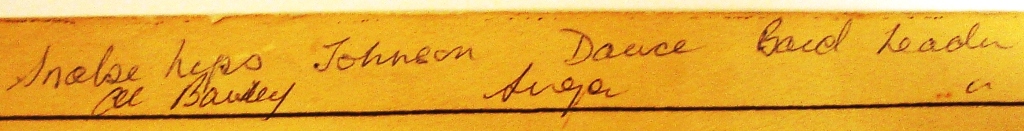

A note written in the margin of the Café de Paris plan names Snakehips Johnson as one of the victims (reference: HO 193/68).

Afterwards, the story was told that Ken had spent the earlier part of the evening with friends at the Embassy Club. When he was unable to find a taxi to take him to perform at the Café de Paris, he decided to walk instead, ignoring his friends’ advice that that the heavy bombing expected that night made this too risky. He arrived at the Café only a few minutes before the bomb fell. [ref] 23. Graves, pages 116-7. [/ref]

After Ken’s death, Mr Cummings, a civil servant in the Colonial Office’s Welfare Department, corresponded with Ken’s widowed mother, Annie, about his funeral arrangements and memorial. [ref] 24. The National Archives CO 981/15. [/ref] In a letter dated 8 April 1942, Annie revealed her feelings about her son’s death: ‘… I am sure you can enter in my position in regards of having to write such sad letters about my dearly beloved son, truly with Ken’s passing it seems as if the last bit of light has gone out of my life.’

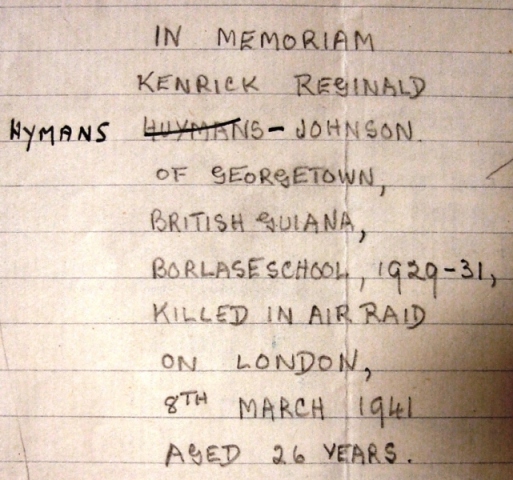

The Colonial Office file also includes a draft of the text for Ken’s memorial at his old school, Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School, in Marlow, Buckinghamshire (reference: CO 981/15).

You can read more about Ken’s life and work on the following websites:

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (subscription required)

- The West End at War

- Black History Month

- Swingtime.co.uk

If you are interested in researching a bombing incident during the Second World War, you may find that a previous post on this blog and our research guide about the Bomb Census and related records are helpful places to start.

Fascinating blog Andrew.

In the detail from HO 193/68 is that Al Bowlly’s name below that of Ken Johnson? Bowlly actually died during a raid just over a month later, but he did sing with Ken Johnson’s band (among others).

Thank you, Sam. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Yes, that does look like Al Bowlly’s name in the margin too – although we know from other sources that he died in a later incident.

There are just these two names written in the margin and they are in different handwriting from the other annotations. We don’t know why the names were added or by whom. It wasn’t usual for individuals to be named on a plan, even in the minority of cases where the Ministry of Home Security wanted a plan of an individual incident.

This is a good example of how different sources of information about Second World War bombing incidents sometimes contradict one another. The discrepancies may be small – for instance, different sources give different times for when the Cafe de Paris bomb fell – or much more significant: although I could only find one bomb mentioned in the Bomb Census as hitting the Cafe de Paris on 8 March 1941, some other sources mention the possibility of a second one.

Andrew,

Interesting. There is also a Treasury file (F12582/085 in T 160/1177) dated 27 June 1941 to 18 May 1944: “Gifts to the Nation: Cafe de Paris; gift to the Exchequer of proceeds of sales of wines” which I hink is the Cafe de Paris in London.

David

Thank you, David. That sounds like an interesting file.

Re Al Bowlly’s name appearing below Ken’s in the fragment pictured above, I had understood that this was because Al’s music folder for Snakehips’ band (with which he used to sing when he was in town – see Ray Pallett’s excellent biography of Al Bowlly: ‘They Called Him Al’) was found in the wreckage of the club…and it was assumed that he’d been present, which wasn’t the case, as you say.

Thank you for your comment, Michael. I didn’t know that.

PS Bowlly’s name looks rather like his own signature (though possibly spelt incorrectly)!

Could the effect of the blast had been felt in Putney? I’m sure my mother told me that the windows of her home in Disraeli Road were blown out by the blast.

I wonder if this might have been a different incident – the dance hall at the Regal Cinema next to Putney Bridge and the Milk Bar under it were hit during a raid on 7 November 1943. I’m sure the effects of this would have been felt in Disraeli Road, which is just up the High Street.

See http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/28/a8128028.shtml for the story.

Thank you for your comment, Monique.

To me, that sounds rather unlikely. Any damage to houses in Putney on the same day would probably have been caused by bombs that fell nearer to them. Also, in cases of heavy bombing it’s not always possible to attribute damage to a particular building to a specific bomb with complete certainty.

It seems to be quite common for there to be some differences between people’s later memories of bombing incidents and what was noted in official records at the time. We can’t always now be certain which is more accurate but neither is infallible.

My mother and family lost their home in Acland Street, Poplar. I can’t find this on maps so does anyone know if the whole street was lost or was it demolished at a later date. My family were the Simmons at number 11, my grandfather was a City of London policeman.

Thanks for your comment, Jenny.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

In this case, though, you might want to try Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives first. Website and contact details for local archives are available in the ‘Find an Archive’ section of our Discovery catalogue: http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/find-an-archive

I was very interested in this article as my mother, father and uncle were passing in a car afterwards, the went down to the ballroom and described to me a young woman sitting at the bar in an emerald green evening dress one arm had been blown off, but she still say at the bar with a glass of fizzy in the other, obviously she was in total shock. It’s just something that’s stuck in my mind.

England amateur international footballer Howard Barnes is reported to have lost a leg when a bomb fell on a “London café” in early 1941. I wonder if it was this one?

Our uncle was killed in THECAFE PARIS bombing 1941, he worked there,. There no no record of his death in the GRO free bmd on line. We also dont know where he was buried. Any ideas please his surname was CHRISTOFI

Dear Pamela. As a starting point you might find this research guide useful: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/deaths-first-and-second-world-wars/.

Try looking at Christofi A Christofi 1d218 Jan-Mar 1941 Distrct Lambeth, death certificate, but the archive says age 0, but that could be because age unknown.

A son of the prominent Canadian distillery firm Seagrams, Philip Frowde Seagram (formerly of Waterloo Ontario) of the 48th Highlanders with a party of Canadian service personnel was killed that night. He was on the staff of Canadian General McNaughton. One of the first prominent Canadians killed overseas in the war. In the wrong place at the wrong time.

I am Sandra Philip Seagram-Annovazzi daughter of Capt. Philip Frowde Seagram of the 48th Highlanders of Canada, ADC to General McNaughthon . My father was buried with full military honours at Brookwood Military cemetery Surrey.

My mother ‘YJD Bryer ‘ ( June) happened to be one of the 10 dancer’s who fortunately was unscathed & survived the cafe de Paris bombing . She was only 16 at the time.

She later immigrated to Nova Scotia, Canada until her death in Feb 2014

Yvonne June Dawn Bryer

Was her full name .

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.