Today marks 60 years since the publication of The Reshaping of British Railways, Dr Beeching’s report on how he planned to improve Britain’s railways.

Many people have heard of the Beeching Cuts, where thousands of railway stations and railway lines were identified for closure during the 1960s. Dr Richard Beeching was the man behind the plan, and became notorious for what many saw as detrimental and unnecessary cuts to a wonderful transport system, in the country which gave birth to the railways. In this blog I want to examine his reasons for taking such drastic action.

Uneven use and effectiveness

During the Victorian period, private railway companies eagerly built railway lines in competition with each other, but many would ultimately prove unprofitable. There were duplicated lines, routes which were underused, and many could not cover their running costs.

Even before Beeching’s plans were published, the railway companies themselves had started to cut unprofitable routes, with 1,300 miles of line being decommissioned during the 1920s and 1930s. After the Second World War, when the railways were nationalised, a further 3,000 miles of track were withdrawn.

During the 1950s the motor car was becoming the transport of choice for many people, and industry was turning to road haulage to move goods and raw materials door-to-door around Britain.

The Transport Act of 1962 abolished the British Transport Commission and replaced it with the British Railways Board, and Dr Beeching was appointed to implement a reorganisation. But Beeching was asked to go further. His mandate was essentially to make the railways pay.

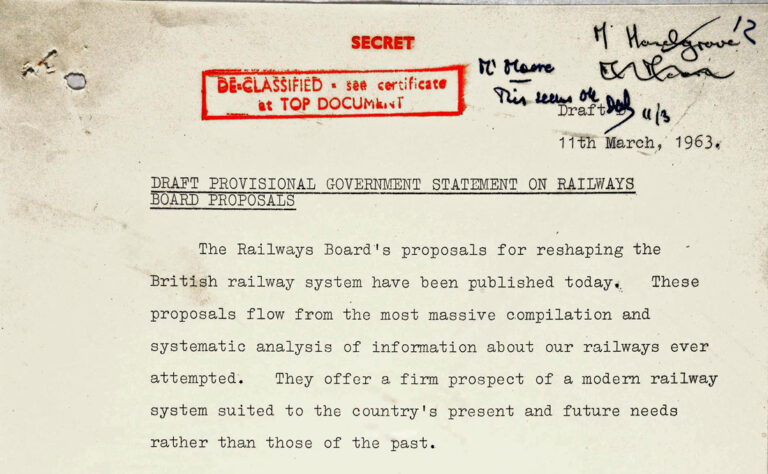

On 27 March 1963, Beeching published his report entitled ‘The Reshaping of British Railways’. The report identified profitable and unprofitable services and revealed great unevenness in the use and effectiveness of railways. It recommended the widespread closure of uneconomic routes. He identified another 2,363 stations for closure, along with 5,000 miles of track, in his report that aimed to prune the railway network back into a profitable concern.

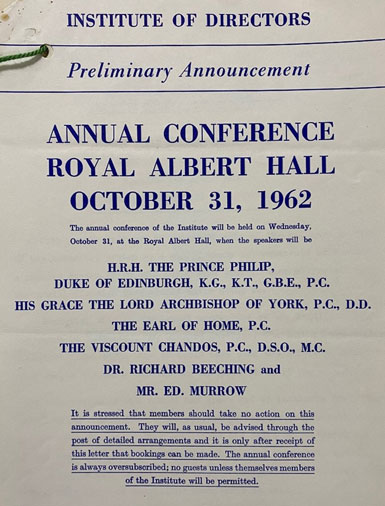

Many have criticised Beeching and his cuts to the railway, but let us examine his reasoning, as revealed in a speech he made to the Institute of Directors in the Albert Hall on 31 October 1962.

A clinical approach

In his address, Beeching stated that an emotional approach to the railways was not helpful, and that there was far too much opinion and not enough understanding of the problem. The key to the whole problem was a proper judgement of the right role of the railways as part of the transport system as a whole. His plan would, he said, ‘create a system which will carry a greater total traffic than at present, and which will flourish financially while doing so.’

A trained physicist, he took a clinical approach to his methodology. This was to assess the characteristics of the product (the railway), both merits and demerits, and to survey what market existed for a product with those characteristics, and then plan to provide the product in quantities to match the need.

The main characteristics of the railway, as he saw them, were:

- Very high fixed costs on maintenance

- High capacity with low movement costs per unit

- The ability to move dense flows of traffic

- Safe, reliable, scheduled movements at high speed

However, history had left him with a rail system which operated in defiance of these basic characteristics.

Freight vs passengers

There was a clear distinction between freight traffic and passenger traffic. They were two distinct markets, and without freight the railways could not exist at all, but it was passenger traffic which excited the greater public interest.

Beeching found that slow-running ‘stopping’ passenger services, operating over routes lightly loaded with any kind of traffic, were simply no longer viable. They were not covering their own expenses and were costing government up to £35m per year. His conclusion was that railways were not suited to provide such services, and if they were to continue they would need to be subsidised. Such a solution sounds good to the passenger, but not so good to the taxpayer who would end up footing the bill.

The real solution would be bus services, which could operate profitably with much lower traffic flows of about 2,000 passengers per week. Then, should subsidies still be required, costs would be much lower for a bus service than for a railway.

Turning to the freight service, there was, he said, enormous potential for growth. Beeching had several ideas on how to make it pay. He wanted to increase the volume of traffic by improving the quality of the service offered, and there were three methods for doing so.

Setting the scene, Beeching explained that the railway had developed over a period when the horse and cart were the only means of delivering goods to and from trains. Carts operating on poor quality roads and tracks meant that the main rail network was extended by an even closer network of branch lines, and close spacing of stations over the whole system, so as to reduce road movement to a minimum. A cart would be unloaded into a single wagon, and so the wagon became the unit of movement for all freight, trundling from marshalling yard to marshalling yard with variable and cumulative delays. This system persisted only because the horse and cart were worse!

The railways had saddled themselves with handling light flows over a multitude of lines, sacrificing their best assets: speed, reliability and low-cost through-train operation. On top of this a huge number of interchangeable wagons had to be managed, in itself creating technical inertia, since new wagons had to match the old ones, so improvements to rolling stock were held back. Beeching’s plan was to create new rolling stock capable of carrying much larger quantities, similar to those used in block trains carrying coal and mineral traffic.

New customers

Beeching’s new customers would be the manufacturers of the rapidly increasing volume of semi-processed and manufactured products that at the time dominated the growth in the UK economy.

In 1962 around 90 million tons of this type of product was being transported by road, which he argued would have been better moved by rail. Most of it moved between the ports and the main centres of industry and population, ie parallel with the main rail arteries of the country. If only half of this transferred to rail it would add £100m a year to government revenues.

Beeching wanted regular, scheduled, through-train services composed of purpose-built stock, and if necessary operated as ‘company’ trains, painted in the customer’s livery. For less regular traffic, trains could be chartered. There would also be ‘liner’ trains operating shuttle services, or running around loops linking industrial centres, which would move smaller or less frequent loads.

Beeching wanted regular, scheduled, through-train services composed of purpose-built stock, and if necessary operated as ‘company’ trains, painted in the customer’s livery. For less regular traffic, trains could be chartered. There would also be ‘liner’ trains operating shuttle services, or running around loops linking industrial centres, which would move smaller or less frequent loads.

These trains would be served by new depots – less than 100 across the country – to which railway-owned road vehicles carrying the new large containers would deliver the goods. The new service would be quick, reliable, shock-free and would be promoted by a phased closure of existing depots and branch lines.

More than just closures

This was Beeching’s plan – a new balance between road and rail, built not on the ‘wild ideas of newcomers,’ but on those that have welled up from thoughtful railway managers.

Beeching’s plan was wide-ranging and ambitious, taking in the British transport system as a whole. It was so much more than simply closing branch lines and stations, for which he became so notorious. But did his scientific and economic approach cloud his judgement regarding the social consequences of his actions? Was the plan a success? The jury is probably still out.

We are still living with Beeching’s actions and many failed subsequent projects at the former British Rail (e.g. APT) with the one success (Inter-City 125 which has now been scrapped). Many towns are still without a railway service which they used to have.

A question: on the rail freight side of the “ledger”, at least up until Brexit, were the proposed changes implemented and did they prove effective?

Was a new balance achieved between through-freight services and efficiency, and multiple stop passenger services on the same line? Was additional trackage and/or lay-by tracks and related signal equipment added effectively to enable more efficient sharing of the lines?

Thanks.

Given the mindset and prevailing attitudes of the time, I think it was inevitable that the Beeching Cuts would have happened in some form or other, indeed, as mentioned a large number of lines were cut through the previous decades as well.

Probably the larger issue was not so much closing the lines, per say, but rather what happened to the land afterwards. If this had been kept as part of a residual transport landbank then reopening lines now, given a vision for more sustainable transport, would be a lot more feasible. To me, selling off the land in such a way as to pretty much block future reopenings is actually the real problem rather than the 1960s closures themselves.

Obviously there is the action of Wilson’s 1964 government and dropping their election manifesto around the closures as well as Ernest Marples questionable links to the road transport and construction industries, but in short, the view was that the road and private transport was the future and that the railways were a relic of the victorian past. It is the legacy of this mindset that we are having to deal with today.

Large towns around the UK were left without proper public services such as Merthyr Tydfil, Leek in Staffs, Leigh in Lancs, the whole of North East Scotland, and many, many more. All of the Beaching cuts were of course not implemented, if they had been, there would have been no railways left north of Perth, or west Aberdeen. However, looking forward there is an impetus which has reopened some closed lines such as The Borders Railway, the Leven, and Oakhampton branches, and with a further possibility of the Aberdeen to Elgin via the Coast Route, Aberdeen to Fraserburgh, and Peterhead lines being reinstated in the years to come.

I have read elsewhere that his closure of uneconomic routes was sometimes based upon poor data quality where observations of passenger volumes on some routes where taken at odd times which did not always truly reflect the real passenger volumes in use. Hence some of the data was skewed and probably led to a number of unnecessary closure decisions, though not all.

Railways would have Stations miles away from the Town or Village they represented. So getting in to a car was easier if you could afford one.

Sixty years later we need some of the axed lines. Some have become Heritage lines. Which provides another Industry in Leasure.

I grew up in a town called Haverhill, which was a New Expanding Town in the 1960’s. 15000 Londoners were encouraged to move to a small town in Suffolk with 4000 original inhabitants as part of the “overspill” movement of the time. The town has a railway that linked Cambridge to Colchester and 2 stations. By 1965, it was all gone, leaving the town as one of the largest towns in England without a railway. The 1970’s hit the town hard and it has always struggled. Ironically, there are now attempts to reopen the line to Cambridge as it would provide a solution to that city’s chronic lack of housing and could create a thriving commuter base for the town. We may go full circle!

A long drawn out process which started with the neutering of Morrison’s original BTC in 1953. Deliberate destruction of any hopes of genuine transport integration in this country. Serpell ex-Treasury as Perm Sec at MOT wreaked havoc. Bung in a v, v dodgy minister in Ernest Marples and you have the closure of a third of the rail system. Lab government inherited the landslide, and carried on, but bless Barbara Castle for getting rid of Beeching and saving a great deal. PSO is her legacy and belief in social needs, not a 19c strict ledger bound approach. Always a good trick of BRB in 1961-62 was to do a traffic survey in middle of school holidays or in mid Jan when far less traveling.

TOTAL actual savings £6M. by 1970 and stripped infrastructure like viaducts and tunnels that still have to be maintained to this day. Ask if scientific and rational in North Devon and Cornwall if you don’t have a car to this day or Scots borders, Norfolk etc, etc.? Attempts at reappraising the cuts simply do not bare close scrutiny. Not everything could or should have been saved, but this was not careful surgery but butchery.

I would argue the jury is no longer out, it retired with a large thumbs down some time ago.

Beeching saw the bus as the solution? Well in todays climate, the bus operators have been cutting routes that do not pay a profit margin offering a dividend, squeezing schedules so that any recovery time for a driver is cut to the legal minimum, not to mention the terms and conditions of employment. Try finding a toilet these days if you are driving a bus route or a lorry on delivery. We now have a chronic shortage of drivers, those who came out of the industry will not be going back.

Our roads and motorways are clogged with traffic, potholes abound, cycle initiatives in towns and cities now causing further congestion on the roads.

Why did Beeching not integrate the canal system in with roads and rail? Certain freight that did not need a speedy delivery could have been floated if our canals had been linked. It would also mean that water could have been more easily been accessed in areas that needed it for industry.

Beechings solutions train left the station some time ago, easier to see with hindsight, yet integrated local hubs with transport links, rather than central nodes, would make more sense. That would involve more power to make decisions at local level, something this country does not have a good track record on.

The Rail Industry failed to make any attempt to cut back on over manning it almost seemed to embrace its own destruction. The promise of replacement bus services should have come with a guarantee of remaining in place for at least 10 to 15 years after the removal of rail services. Freight seemed also determined to self destruct with the removal of Speedfreight service. On a positive note glad to see the reopening of lines and return of stations to Scotland. Freight needs to be worked a decent service to the south could be a better investment than the upgrade of the A9 and A96.

Reshaping made no mention of all of its legacy costs, or its means or method. The cost in the landscape of abandonment after hasty, frequently careless demolition and incomplete recovery, left tawdry trails of ironwork, bricks and smashed equipment along unprotected trackbeds.

Missing from this story is the fact that the Minister of Transport who appointed Beeching was Ernest Marples – a man who owned a major road construction company and could therefore hardly be said to have been an “uninterested” party.

[Admittedly he “transferred” ownership to his wife during his tenure at Transport, though she appears to have had no input into the company at all].

To be fair the Report also had many good points; it outlined the development of long distance “Inter-City” passenger services (often forgotten) and did lead to considerable improvements in freight services by concentrating on what the railway could do well (bulk freight, fast regular “Freightliner” routes etc.).

However, it’s certain that the cuts went much further than in comparable European countries and left many communities bereft of viable public transport options.

There was also no consideration of concerted attempts to encourage ridership on “underused” routes, attempting to integrate services with the privately operated bus services etc.

And yes, the actual measurement of passenger use was eccentric to say the least – one week in winter – which hardly helped services to coastal resorts to prove their worth for example.

Most notoriously of all, the Report somehow didn’t list Beeching’s own local station and line (Maidstone West) for closure, even though busier lines and stations were slated to go!

I remember seeing the Beeching report when it was published. My father was a railway engineer; he brought his copy home and we looked at it together.

Beeching’s name is associated with cuts but it can be argued that he should be recognised for saving more of the rail network than his political masters expected. Road transport was expanding so fast that we could have easier ended up like the USA, with almost no railways at all.

I remember the report coming out when I was 10. Amazingly us kids at school all saw the cuts of services as being too savage. As too often, the commercial and economic considerations were considered more than the long term social costs. Cambridge needed a larger workforce, Haverhill was being expanded to provide this. Its rail route into Cambridge was key to this and yet the station and line were cut. Similar errors were made throughout the country. Finally, rather than retaining the land used by old railways it was sold off rather than kept to facilitate the resurrection of local lines in the future. As so often our national planning is far too short term.