The 18th of November 1910 is one of the iconic dates in the history of the women’s suffrage movement. It was a day that saw police and suffragettes battling on Parliament – a dramatic turn of events that changed the movement for ever.

The Women’s Social and Political Union

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) had been founded in 1903, determined to try to get votes for women by any means necessary. Founded by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, the group was frustrated by the many prior decades of slow progress and disappointments.

The WSPU’s policy of direct action had begun in 1905, when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney interrupted a meeting to ask politicians whether they were in favour of votes for women. In the following years the methods and tactics developed, often organically, as the women repeatedly felt their voices weren’t being listened to. It was this group that led the November 1910 Black Friday protests. They went by the name, the Suffragettes.

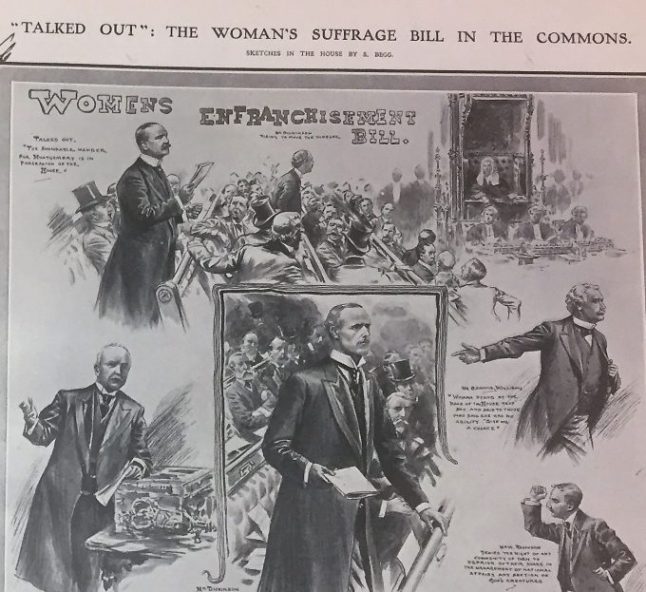

Women’s Suffrage Bill being talked out of the Commons, March 15 1907. Illustrated London News, 1907 Jan-June. Catalogue ref: ZPER 35/130

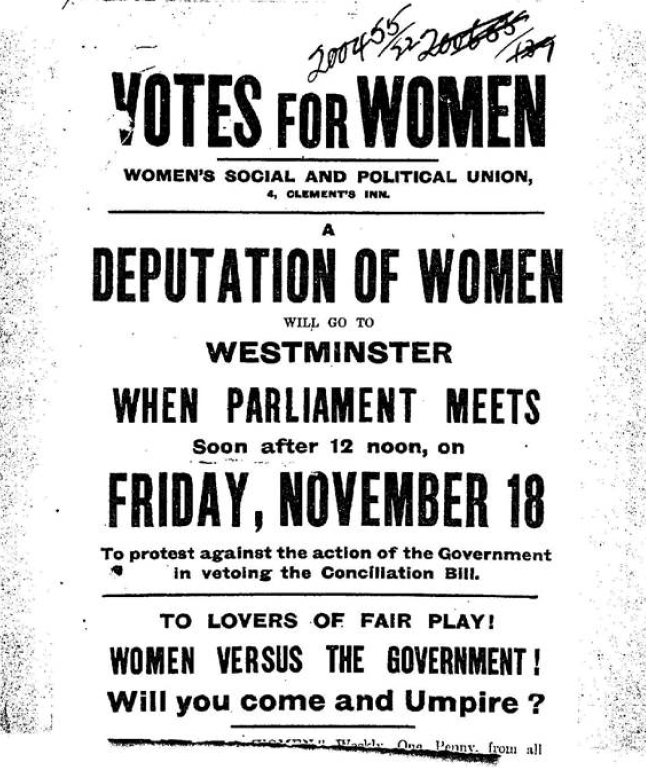

The WSPU advertised the Black Friday deputation with this handbill, which pitched the demonstration as ‘Women versus the government!’ Catalogue ref: HO 144/1106/200455

Why were the Suffragettes protesting?

History often depicts militant suffrage supporters as disorganised, hysterical and reckless. However, suffrage protests were often targeted thoughtfully and held in response to a specific action, or more often a lack of action, by the government.

In this instance it was the 1910 Conciliation Bill. The Conciliation Bill was designed as a partial compromise, as the name suggests, to appease suffragettes. It offered the chance of a limited franchise for women through a private members bill. If it passed it would have enfranchised approximately one million women on the basis of a property qualification. As a gesture of goodwill the Suffragettes suspended militant activity until the fate of the bill was decided. This took several months and it was eventually carried by 109 votes. However, it quickly became clear that Prime Minister Herbert Asquith had no intention of giving further time to the bill.

Black Friday

On 18 November 1910 controversy over ‘the people’s budget’ triggered a general election, and Asquith announced that parliament would be dissolved on 28 November, leaving no further time for the Conciliation Bill. The Suffragettes’ fears were confirmed.

In response to yet another disappointment for the movement, Emmeline Pankhurst took to the streets. More than 300 suffragettes marched from their meeting at Caxton Hall (a regular haunt of the suffrage movement) to Parliament Square.

The demonstration was led by some key figures in the movement, including Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Emmeline Pankhurst herself. The suffragettes were met by a large police presence. Controversially, instead of arresting the women, as was previous precedent, violent clashes ensued. Over the next six hours 200 women were assaulted; there were claims of police misconduct, acts of violence and sexual assault. Descriptions of the women’s experiences are vivid and chilling.

Miss Christina Richardson, listed as ‘an elderly woman’, was part of the demonstration; she described what she witnessed:

‘I saw a policeman grab women by the collars, shake them and fling them aside like rats. I saw them take women up and fling them on the crowd as many logs on a wood pile…’ [MEPO 3/203]

There are few surviving photographs from the protest, but one iconic image prevails. The subject is Ada Wright, and her photo became front page news. In her history ‘The Suffragette Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals’, Sylvia Pankhurst described Ada’s plight:

‘I saw Ada Wright knocked down a dozen times in succession. A tall man with a silk hat fought to protect her as she lay on the ground, but a group of policemen thrust him away, seized her again, hurled her into the crowd and felled her again as she turned. Later I saw her lying against the wall of the House of Lords, with a group of anxious women kneeling round her.’

Ultimately the police arrested four men and 115 women, although all charges were dropped the following day.

Photograph of Ada Wright from the Black Friday protests. It was to become an iconic image of the suffrage movement. Catalogue ref: COPY 1/551

Calls for an inquiry

In response to the shocking treatment of suffrage supporters on Black Friday, many individuals and organisations issued outraged calls for a public inquiry. How had this been allowed to happen?

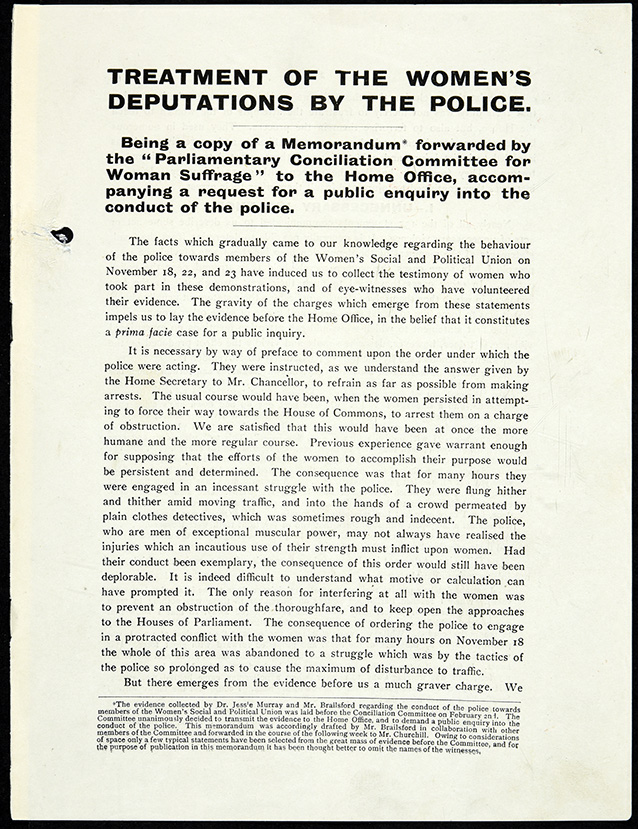

The conciliation committee of MPs who had been pushing for the women’s suffrage bill in parliament took it upon themselves to investigate. They collected the testimony of women involved and bystanders in an attempt to understand the protest. They claimed:

‘The gravity of the charges which emerge from these statements impels us to lay the evidence before the Home Office, in the belief that it constitutes a prima facie [at first glance] case for a public inquiry.’ [MEPO 3/203]

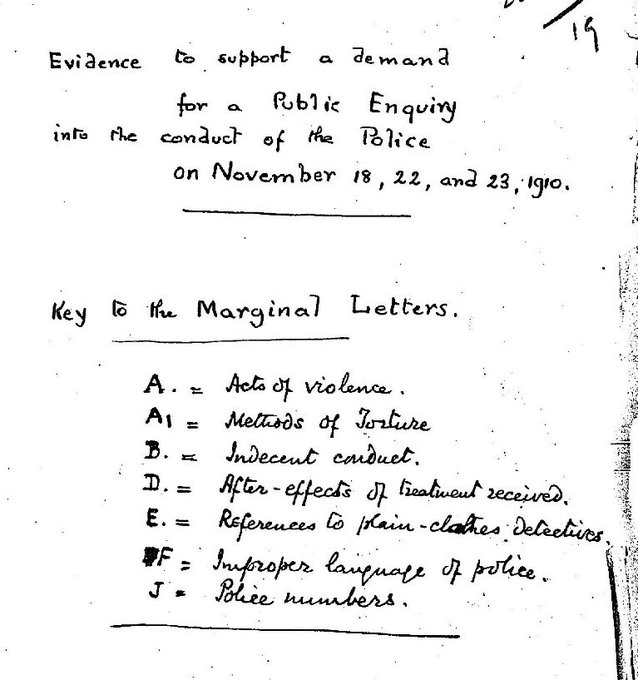

The evidence was gathered by Dr Jessie Murray, herself a suffragette, and Mr Henry Brailsford, a journalist and founding member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. Eventually 135 testimonies were recorded under a range of categories, and ultimately 29 of the statements included details of sexual assault.

The subsets of evidence themselves speak volumes, such as, ‘Methods of Torcher’ and ‘Indecent Conduct’.

Image of the front page of a pamphlet entitled ‘Treatment of the Women’s Deputations by the Police’, which was forwarded to the Home Office by the Conciliation Committee. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/203

Key to evidence submitted after the Black Friday protests by suffragettes. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/203

However, a range of other material was also submitted to the Home Office. One account said that ‘the women deliberately assaulted and did their worst to provoke the police – who behaved in a most patient way’. [MEPO 3/203]

The suffragette Rosa May Billinghurst described her treatment at the protest. Rosa was known as the ‘cripple’ suffragette. Having been disabled since childhood, she used a hand tricycle to get around. You can read more about Rosa in my colleague Katie’s blog, Rosa May Billinghurst: suffragette, campaigner, ‘cripple’.

Rosa May Billinghurst depicted in her hand tricycle in a copy of The Suffragette. Catalogue ref: ASSI 52/212

In the evidence collected, Billinghurst recalled the treatment she received on Black Friday in 1910. The report does not name Billinghurst but instead calls her ‘a cripple lady’:

‘I am lame and cannot walk or get about at all without the aid of a hand tricycle, and was therefore obliged to go to the deputation riding on the machine. At first, the police threw me out of the machine on to the ground in a very brutal manner…I may also add that my arms and back were so badly bruised and strained by the rough treatment of the police that for two days after Friday 18th I could not leave my bed.’ [MEPO 3/203]

However a hand-written note from a witness noted that the police acted with ‘extreme forbearance’ in relation to Rosa, describing her as repeatedly driving ‘her hand tricycle at their ranks’. As this example shows, much of the evidence around the protests was controversial and contradictory.

Suffrage martyrs?

In the aftermath of these protests two deaths became associated with Black Friday. The death of Mary Clarke, the sister of Emmeline Pankhurst, has been attributed to Black Friday and her experiences in the days afterwards; she was said to have been weakened by her involvement in these suffrage struggles and died on Christmas Day 1910 of a brain hemorrhage. The second suffragette was Henria Williams, who prior to the protests had a weak heart. Her testimony described in her own words:

‘One policeman after knocking me about for a considerable time, finally took hold of me with his great strong hands like iron just over my heart…I knew that unless I made a strong effort…he would kill me’. [MEPO 3/203]

While the evidence compiled by Murray and Brailsford could not find a direct link between Black Friday and the death of Mary Clarke, they felt there was evidence linking Henria Williams’s death to her treatment at these protests.

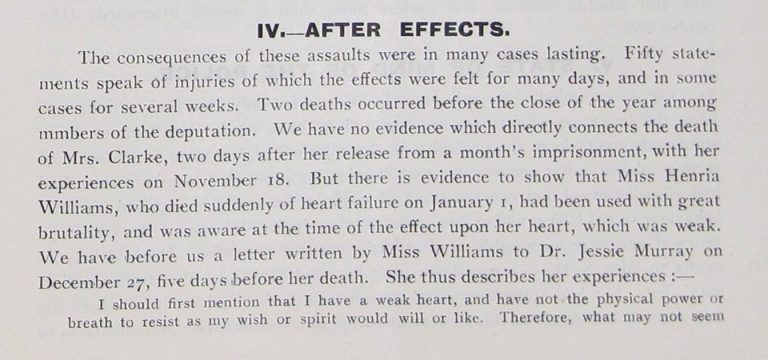

Extract from the pamphlet ‘Treatment of the Women’s Deputations by the Police’ commenting on the deaths of suffragettes Mary Clarke and Henria Williams. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/203

Despite this, calls for a public inquiry were controversially rejected by Home Secretary Winston Churchill.

After these violent clashes between suffragettes and police outside Parliament, methods of protest changed. Suffragettes believed increasingly that the government cared more about broken windows than a woman’s life. Mass window smashing campaigns and the targeting of MPs’ houses became more common forms of protest for the WSPU. You can follow the increasingly militant actions of the suffragettes through some of our other blog posts. The police also changed their approach, in an attempt to avoid such events in the future.

Black Friday was certainly not the end of the suffragettes’ battle against the State. Indeed in many ways it signified a starting point for a whole new era of campaigning. It does however typify the relationship between the government and militant suffrage supporters – constantly fraught, difficult and controversial.

This blog post uses research by various colleagues from The National Archives 2018 Suffrage 100 season.

Amazing photos and it is really heartwarming to learn of the bravery and determination of these suffragettes.The state today and some of the police display similar attitudes of misogyny and violence.There is still a lot to do and important to have these women from the past as our role models.