Thursday 26 April 2018, 14:00

Thursday 26 April 2018, 14:00

Suffrage 100 – Suffragettes in trousers: male support for women’s suffrage in Britain

Suffrage 100 is a season of events and exhibitions at The National Archives from February to October 2018 marking the centenary of the passage of the Representation of the People Act 1918 giving the vote to some women.

It is interesting to see how a public man viewed the question of women’s suffrage. As a celebrated writer, the novelist and poet Thomas Hardy was frequently asked his views on important topics of the day. A private man, he was inclined to keep his views from the public and often refused to endorse or support causes even when he was in sympathy with them.

In 1892 he had been approached to become a vice president of the Women’s Progressive Society whose chief aim was women’s suffrage. He declined, however, admitting that he had not yet been converted to the object of women’s suffrage – although he went onto say that he was in sympathy with many of their other objectives.

His wife Emma Lavinia Hardy was a supporter of the suffrage movement and a member of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage. She could be critical of her husband’s views. In 1894 she had written that Hardy’s interest in the cause of women’s suffrage was ‘nil’ and went on to say: ‘He understands only the women he invents – the others not at all.’[ref]Michael Millgate (editor), Letters of Emma and Florence Hardy (Oxford, 1996), Emma Hardy to Mary Haweis, 13 November 1894.[/ref]

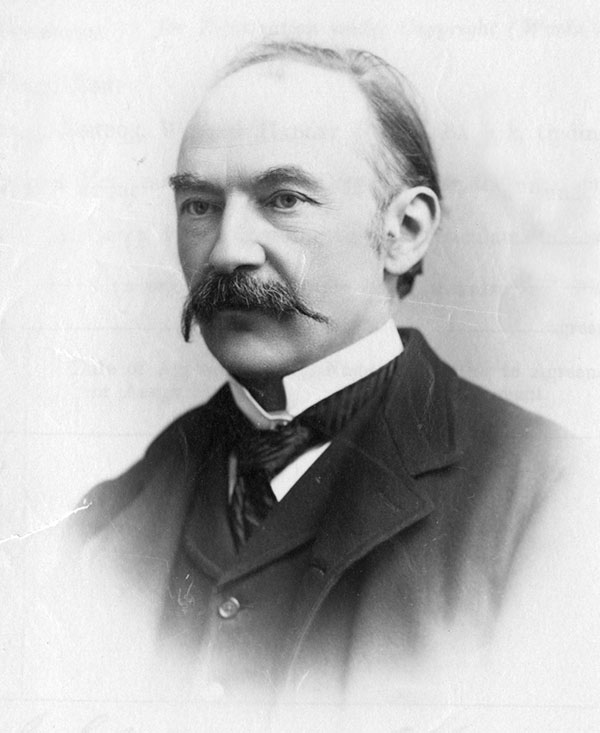

Thomas Hardy, writer and novelist. Catalogue ref: COPY 1/417/210

However, Hardy was passionate about a number of causes, which he believed would be furthered if women had political influence. He supported, but did not endorse, an article written by Agnes, Lady Grove, ‘Objections to Women Suffrage Considered’, published in ‘Humanitarian’ in August 1899. In July 1900, Hardy wrote to the journalist W E Hodgson that, in his opinion, the British constitution worked better under female monarchs rather than kings and suggested that the crown should descend through the female line. He had been asked to write an article on the subject but declined, as he felt it would be misconstrued.

Although not an active supporter, Hardy appears to have attended some suffragist and suffragette meetings. He appears to have been present at the meeting in Exeter Hall in the Strand on 19 May 1906, after the morning demonstration by the Women’s Social and Political Union. This was followed by a mass meeting in Trafalgar Square organised by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. In November 1906, Millicent Fawcett wrote to him asking for his views on women’s suffrage and if they could be published along with those of other eminent men in a pamphlet. Hardy expressed his support for women’s suffrage in a letter to her of 30 November 1906:

I have for a long time been in favour of woman-suffrage [sic] … I am in favour of it because I think the tendency of the woman’s vote will be to break up the present pernicious conventions in respect of manners, customs, religion, illegitimacy, the stereotyped household (that it must be the unit of society), the father of a woman’s child (that it is anybody’s business but the woman’s own, except in cases of disease or insanity), sport (that so-called educated men should be encouraged to harass & kill for pleasure feeble creatures by mean stratagems), slaughter-houses (that they should be dark dens of cruelty), & other matters which I got into hot water for touching on many years ago…[ref]R L Purdy and M Millgate (editors), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy (Oxford, 1982) III, 238-39, Hardy to Millicent Fawcett, 30 November 1906[/ref]

Mrs Fawcett thanked him for his comments but thought that ‘John Bull’ was ‘not ripe for it at present’ and so his letter was not published.

In February 1907 his wife Emma went up to London to take part in the suffragist procession from Hyde Park to Exeter Hall, which became known as the mud march because of the terrible weather. In May 1908 Emma wrote a letter published in ‘The Nation’ demanding not only the vote but also that women should also have a place in government ‘not to supersede men’s rule, but to share it, standing on the same platform with equal rights’.[ref]The Nation, 9 May 1908.[/ref] The following month on 21 June 1908, Emma with other distinguished ladies travelled in carriages ahead of the rally of 50,000 people converging on Hyde Park.[ref]Andrew Rosen, Rise Up Women! (London, 1974) p. 104[/ref]

Emma was no militant and Hardy had no fear that his wife would start chaining herself to railings or breaking shop windows. In 1909 she resigned from the London Society for Women’s Suffrage because she disapproved of militancy.

Hardy stated his view clearly, if condescendingly, in a letter to Helen Ward of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in December 1908. He felt that men in sympathy with the cause ‘should be permissive only – not cooperative’: his reason being that women did not realise what the consequences of giving the vote to them would be. In a very pessimistic view he wrote:

I refer to such results as the probable break-up of the present marriage-system, the present social rules of other sorts, religious codes, legal arrangements on property, etc (through men’s self protective countermoves.) I do not myself consider that this would be necessarily a bad thing (I should not have written ‘Jude the Obscure’ if I did) but I deem it better that women should take the step unstimulated from outside. So, if they should be terrified at consequences, they will not be able to say to men: ‘You ought not to have helped bring upon us what we did not foresee.’

Consequently he concluded: ‘I am not disposed to be active in the cause.’[ref]R L Purdy and M Millgate (editors), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy (Oxford, 1982) III, 360 Hardy to Helen Ward, National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, 22 December 1908.[/ref]

He believed that, once women had the vote, ‘men could strike out honestly right & left in a way they cannot do while women are their dependents, without showing unchivalrous meanness’. Giving the vote to women would free both sexes, ‘all superstitious institutions will be knocked down or rationalized – theologies, marriage, wealth-worship, labour-worship, hypocritical optimism, & so on’.[ref]Ibid (Oxford, 1984) IV, 21 Hardy to Clement Shorter [Early May 1909].[/ref]

His dilemma was that, while he thought women should have the vote by right, he wasn’t convinced that they would use it wisely. However, he always refused to support those opposed to women’s suffrage. In July 1910 he declined to sign an anti-suffrage letter when asked to by Lord Curzon. In 1918, when some women got the vote, he made no comment on it – at least in public. Despite his misgivings, which were unfounded, he considered women’s suffrage a step forward in the equality of the sexes and a progressive measure leading to much needed social change.

On 26 April here at The National Archives there is a talk Suffragettes in trousers: male support for women’s suffrage sharing the stories of men who supported the campaign for women’s suffrage.

Thank you for this informative blog. It is interesting to compare Hardy’s notions regarding woman’s votes by comparing them with today’s results. After 100 years has passed women are still looking for equality in many sections of society. Particularly in the third world religions and customs.