This 16th century drawing of St George and the dragon forms part of a frontispiece to a decree and order book from the Court of Augmentations. (Reference: E 315/91)

Regular readers of our blog may recall that a year ago my colleague Jenni Orme wrote a blog post marking the fact that 23 April is St George’s Day. One year on, I have decided to re-visit St George from a different angle.

This 19th century drawing of St George and the dragon is a design for a carved wooden panel in the Houses of Parliament. (Reference: WORK 29/2594)

St George is said to have been a Roman soldier from Cappadocia (in present-day Turkey) who died as a Christian martyr in the early 4th century AD. [ref] 1. See, for instance, D Attwater and C R John, The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, 3rd edition (London, 1995), pp 152-153. [/ref] A popular legend about him is that he fought against and killed a dragon in order to rescue a princess. Over the centuries, many artists have produced rather romanticised images of this battle, often portraying George as a medieval knight – or what they imagined a medieval knight might look like – with weapons and clothing dating from roughly a thousand years after his lifetime.

English artists have been particularly fond of depicting St George because he is recognised as England’s patron saint. We share him with many other places and groups of people, including soldiers, farm workers, the Italian city of Genoa, and the eastern European country of Georgia.

Probably the best-known use of the image of St George by the British government has been on coins, especially gold sovereigns. In 1817, the engraver Benedetto Pistrucci designed a reverse (tails) side for this coin showing St George and the dragon. [ref] 2. ‘The Legend of St George the Dragon Slayer’, Royal Mint website. Like all UK coins, the obverse (heads) side bore a portrait of the monarch. [/ref] You can see an 1817 sovereign on the Royal Mint Museum’s website.

Although they are no longer in general circulation, gold sovereigns are still produced as bullion and as commemorative coins. Their nominal face value remains one pound, just as it was in 1817, but their true value is, of course, much higher. Most modern issues of the sovereign still use a version of Pistrucci’s design. [ref] 3. ‘The History of the Gold Sovereign’, Royal Mint website. [/ref]

As St George is a symbol of England rather than of the UK as a whole, his use on coins has occasionally been controversial. [ref] 4. St George is not the patron saint of the whole of the UK, only of England. If you live outside the UK and are not sure of the differences between the United Kingdom, Great Britain and England, this YouTube video by C G P Grey explains them quite clearly. You may also find this post on the Family Recorder blog and the Uniting the Kingdoms exhibition on our website interesting. [/ref] A Royal Mint file dating from 1925, now held here at The National Archives, provides an example of this. [ref] 5. MINT 20/968. [/ref]

On 26 February 1925, a Scottish MP called John Brown Couper asked a parliamentary question about whether there any plans to change the design of sovereigns to something less specifically English and more representative of the UK as a whole. (Mr Couper suggested Britannia as a suitable alternative.) The file includes an official’s sarcastic suggestion for what the reply should be:

‘The Hon[ourable] Member is under a misapprehension in believing that Pistrucci’s well known design is not representative of the United Kingdom. The George, of course, represents England – and the Dragon whom he has subjugated the remaining and outlying portions of the United Kingdom.’

I do not know whether Winston Churchill, who at that time was Chancellor of the Exchequer and whose job it was to answer the question formally, ever saw the official’s comment. If he did, he wisely ignored it. The file also records the answer that Churchill actually gave, which was this: ‘I am not aware of any intention to mint new gold coinage.’

There is a slight twist to this story. The Royal Mint did actually produce some gold sovereigns in 1925, and it did use the St George and the dragon design on the reverse. [ref] 6. ‘Gold Sovereigns: George V, the Great War and the End of Gold Coinage in Circulation’, London Mint Office website’. [/ref]

What nobody in 1925 could have foreseen is that the story ends with a second twist. Between 1968 and 1975, the Royal Mint moved the production of coins from London to Llantrisant, near Cardiff. [ref] 7. ‘Llantrisant’, Royal Mint Museum website. [/ref] Although today’s gold sovereigns still bear the image of St George, they are made not in England but in Wales, the land of the red dragon.

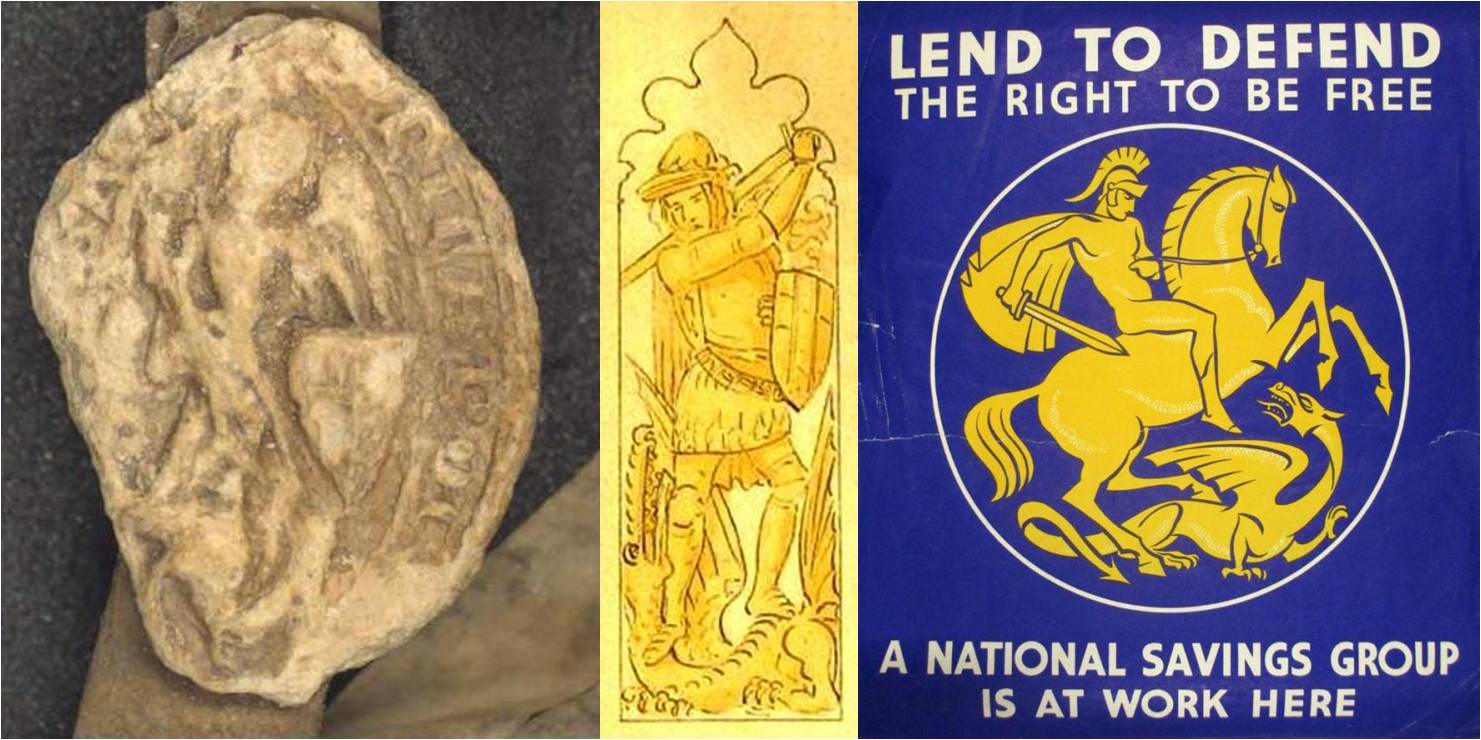

Left: This 13th century seal is thought to depict St George and the dragon. (Reference: DL 25/2063/1718). Centre: Another 19th century drawing of St George and the dragon. (Reference: WORK 29/795). Right: This 20th century poster depicting St George and the dragon was produced by the National Savings Committee during the Second World War. (Reference: NSC 5/35)