In a series of blog posts on medical technology in the First World War, we’ve attempted to cover many of the ways warfare influenced people’s lives well beyond the war itself. This month we focus on vision loss, and on convalescence homes during and after the conflict.

There are many reasons soldiers, and indeed civilians, lost their sight during the war. Some injuries were more immediate, such as shrapnel wounds, and others could be diagnosed long after the conflict, with blindness caused by mustard gas being reported 20 years after the war’s end.

A group from St. Dunstan’s Torquay Annexe visiting the seaside, from St. Dunstan’s annual report 1929 (catalogue reference: PIN 15/1061)

In 1914 St. Dunstan’s Hostel for Blind Soldiers and Sailors was founded by Sir Arthur Pearson, author of Victory Over Blindness. A year later it moved to a property in Regent’s Park. The idea was to provide a hostel where ex-servicemen would go after they had received hospital treatment to ‘learn to be blind’.[ref] 1. Catalogue reference: PIN 15/1061[/ref] The legacy of the war meant that in 1921 men were still waiting to be accomodated, with 57 men awaiting admission. By 1929 there were still two thousand men in their care. The intake included 103 colonial ex-servicemen who were trained during their time at St Dunstan’s. [ref] 2. Julie Anderson, War, disability and rehabilitation in Britain (2011, Manchester University Press)[/ref]

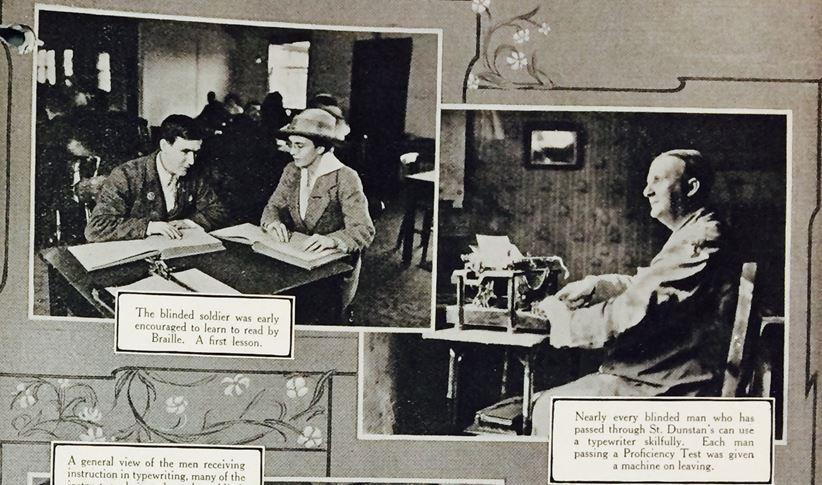

The emphasis of the organisation was training, which often involved varying forms of technology that enabled the men to utilise their skills. This included adapted typewriters and telephones, with standardised assessments to encourage employment. St Dunstan’s often found itself in the papers and, as a more understood form of ‘disability’, attracted public sympathy.

Image from St. Dunstan’s annual report, showing training in progress, 1929 (catalogue reference: PIN 15/1061)

Not all blind people got this kind of treatment – as with disabilities more generally at this time veterans were in a unique position of being seen as particularly deserving of support. Julie Anderson has remarked that ‘Blind people were the most politically active disabled group during the immediate post-war period’. In 1920 there was a march of 250 blind people in support of the passage of the Blind Persons Act, 1920. None of the men from St Dunstan’s were claimed to have been involved. [ref] 3. Julie Anderson, War, disability and rehabilitation in Britain (2011, Manchester University Press) p.28 [/ref]

Numerous pension files detail the experience of men at St. Dunstan’s, including several annual reports. A treasury file also explains more peripheral concerns around convalescence of blind ex-servicemen. In 1918, concerns were raised about the taxation on good arriving into the country. The goods consisted of 800 braille watches sent from Switzerland for the men of St Dunstan’s given by the National Association of Goldsmiths.[ref] 4. Catalogue reference: T 172/1435[/ref] An original watch can be seen in the Imperial War Museum’s collections.

Braille pocket watch for use by blind or partially sighted British ex-servicemen at St Dunstan’s in 1919 (image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum)

The file shows the importance of being seen to support veterans – with Bonar Law, at this time Chancellor of the Exchequer, writing to the organisation to state the Prime Minister could not waver the law to change the payment, but had arranged the duty to be paid from a special fund. Clearly gestures such as this from the government were seen as important to morale among ex-soldiers injured in the war.

However St Dunstan’s was not without controversy. In June 1923 The National Union of the Professional & Industrial Blind of Great Britain and Ireland complained that St Dunstan’s was undermining the professions of blind workers by putting their work on the market for less than the cost of production. It was voted on at conference:

‘This Conference vigorously protests against the action of the authorities of St. Dunstan’s in placing goods, more particularly mats, upon the market at prices considerably below the cost of production… merits the strongest condemnation and we urge the competant authorities to make a thorough investigation'[ref] 5. Catalogue reference: PIN 15/1060[/ref]

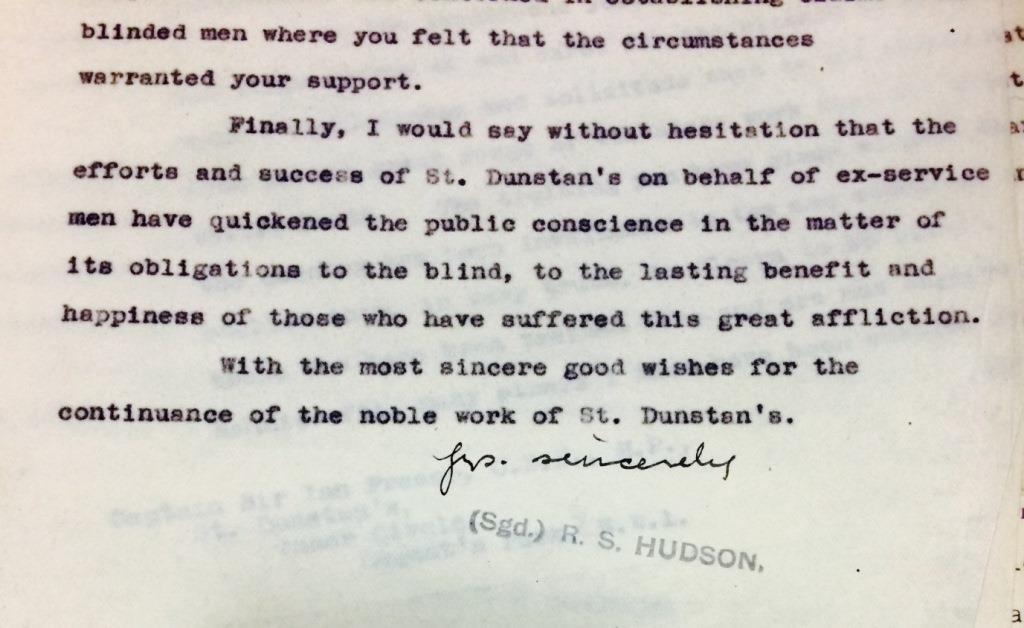

A letter regarding St Dunstan’s however notes the ultimate positives of the organisation, not only did it look after blinded veterans but it was a factor in changing public awareness of people living with blindness. In the aftermath of the First World War this appears to have been St Dunstan’s key legacy.

Letter regarding the legacy of St. Dunstan’s (catalogue reference: PIN 15/1060)

Look out for our Disability History Month Keeper’s Gallery display from 1 December, on the theme of ‘First World War: Impact on Physical and Mental Health’. It will display a cross section of the items we hold on these themes.

Image from an appeal for funds by Captain Ian Faser (also blinded in the Somme in 1916), 1929 (catalogue reference: PIN 15/1061)

The work of St Dunstan’s continues today, though it now generally uses the name Blind Veterans UK.

Interesting that the braille watch appears to have a piece of the ribbon used for the 1914 (or 1914-15) Star attached to it.

I am slightly confused over the part played by the Treasury and Andrew Bonar Law, Treasury file T 172/804 (not stated in your blog) was about the Entertainments Tax payable on a concert for St Dunstan’s in 1918, but the issue of the import tax (T 172/1435) dates from 1923 (according to Discovery). I am also confused by the reference to Andrew Bonar Law (I am not sure which Treasury file you are referring to) as according to wikipedia (not always correct1) he resigned from being Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1921 and when he returned to Government in 1923 he was Prime Minister until his death later that year.

Just a minor correction, but Bonar Law actually returned to government in 1922. He spoke against continuing the coalition with Lloyd George at the famous Carlton Club meeting on 19 October, and became prime minister a few days later. Ill health finally forced Bonar Law’s resignation in May 1923, and he died the following October.

Hello David.

Thanks for the comments.

The Treasury file T 172/1435 references several occasions where import tax was requested by St Dunstan’s to be waived for the import of braille watches. The first from 1918, while Andrew Bonar Law was still Chancellor of the Excheque, appears to be included as evidence for the duty to be waived a second time in 1923.

Thanks for this very interesting post, Vicky, and the light it sheds on aspects of the early history of what is now Blind Veterans UK. Just to clarify and amplify some of the points mentioned: the charity was actually founded in January 1915 as the Blinded Soldiers and Sailors Care Committee and became generally known as St Dunstan’s following its move to St Dunstan’s Lodge in Regent’s Park in March of that year. Whilst it’s quite correct to stress the importance that was placed on training to acquire new skills and, amongst other things, gain employment, there was also always a commitment to a wider and lifelong support; so, by 1929 the majority of those in our care would have completed their training and returned to living at home and would have been supported there by our visiting ‘After-care’ staff.

Blind Veterans UK values, and continues to be inspired by, its history. We hold our own archives, and some related artefacts including a number of Braille watches, at our headquarters in London. Enquiries from anyone interested in any aspect of our history are welcome (archives@blindveterans.org.uk or 020 7616 7933). Rob Baker, Information and Archives Officer, Blind Veterans UK

Hello Rob,

Thanks so much for sharing this information. It’s great to hear Blind Veterans UK has there own archival material that can be accessed. I would certainly love to visit one day.

I found a Buren Braille Pocket watch on eBay and have had it repaired to working condition. It is stamped with the serial 890 which would imply more than 800 were issued. Is there any record of who was issued which pocket watch as I would love to trace its history.

Thank you.

DR McMahon (Royal Corps of Signals)

My father was a St Dunstaner, and in 1929 I was baptised, Jack Dunstan Clamp, at the chapel of St Dunstans’ Annexe at Brighton by W R Davidson, Prebendary of Chichester, Head Master of Brighton College. I understand that the font was made of silver. Is it still existing?

I am sad to see the demise of the centre at Ovingdean although I appreciate that it has had its day. In 1939 I was in Brighton and was able to visit the new building and to meet with my god-mother, Matron Winifred Boyd-Rochford, who gave me a tour of the new building.

Carry on with your good work.

Jack D Clamp.

It has been stated that Jim Corbett enabled the profits from his books on hunting be given to St.Dunstans, did these monies only go to the british soldiers only or were the monies go to the Indian soldiers as well ?

What an amazing organisation. I’ve just discovered that my grandfather James Ingram was at St Dunstans after being blinded in 1915. He is shown in pictures on this website winning the London Brighton race three years running. Are there any archives about residents still existing? The story goes further as it seems he may have had a relationship with one of the volunteers Elizabeth Clark who spent much time there helping the residents. I would love to learn more about either of them during this time.

My grandfather, Robert Holtham Hardy was blinded in Poziers in August 1916. He was a patient at St Dunstans and trained as a masseur. He returned to Australia in 1921 and used these skills to help cute shellshock victims at Caulfield Military Hospital in Victoria. He was English by birth and lived in Lancashire before immigrating to Australia with his parents when he was 14 years of age

I am extremely interested in the St. Dunstan’s history, and in particular, early teaching staff. My grandfather Sydney P Westward taught mat weaving there. I believe that he arrived at the facility

around 1914 or 1915. His wife Elizabeth Westward, may have worked or volunteered there at the same time.

The 1921 UK Census shows my two 2nd cousins, 2x removed working at St. Dunstan’s Hostel, Regent’s Park, London for Sir Arthur Pearson. Dorothy Field age 24 is listed as Private Secretary and her sister Maud Frances Field age 23 as doing Secretarial Work.