The British music scene was changed forever by the arrival of people from the British West Indies and others who came to settle from across the Empire and Commonwealth in the post-war period.

Jazz, blues, and calypso introduced sounds to Britain that were infused with Latin American, African and Asian influences, exploding onto a scene dominated by popular big band sounds from the 1930s to the 1950s. The fusion of Jamaican reggae and British dance music produced Drum and Bass and Dubstep, styles which would subsequently give way to contemporary genres that are popular today, like Garage, Jungle and Grime (see footnote 1).

In acknowledgement of the way that post-war migration changed the way that Britons listened to and made music, and to mark the 75th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush, The National Archives have produced a playlist with reference to records from our collection. You can access it here.

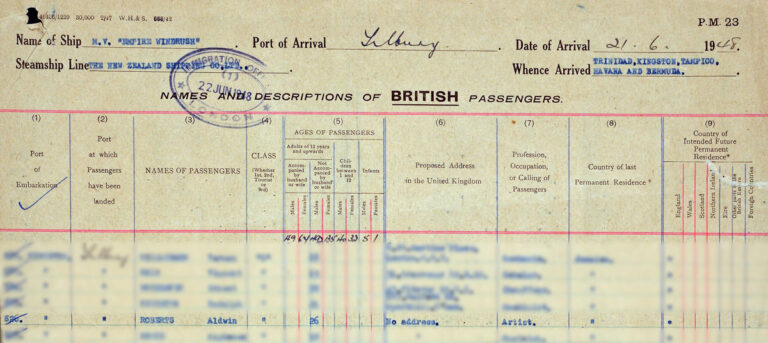

Lord Kitchener (Aldwyn Roberts), London is the Place for Me (1948)

Singing into the mic of a Pathé news reporter, Aldwyn Roberts, who introduced himself to the British Press as Lord Kitchener, quickly became one of the most influential calypso artists in Britain and in the Caribbean (see footnote 2). Although the song seems to paint arrivals as hopeful, ever-optimistic and patriotic, the tradition of political commentary in calypso music moved beneath the acapella bars that Roberts spontaneously burst into at portside (see footnote 3).

Calypso music challenged racist attitudes and empire through its use of lyrics and double entendre, and its traditions were developed by enslaved people taken forcibly to the Caribbean by European imperial powers. The British banned drumming in Trinidad in 1883 in response to clashes between revellers and the police during the annual celebration of Canboulay – a celebration that commemorated the harvesting of burnt cane fields during slavery. It was this change in the law which eventually led to the innovative use of steel pans, initially anything from frying pans to dustbin lids, which now forms an integral part of calypso music today (see footnote 4).

Aldwyn Roberts is recorded on the Empire Windrush Passenger List as one of the five ‘Artists’ aboard and used his music to highlight the racism faced by arrivals from the Caribbean. Returning to Trinidad fourteen years after his arrival in Britain, Aldwyn Roberts recorded music up until his death and is regarded as the ‘grandmaster of calypso’.

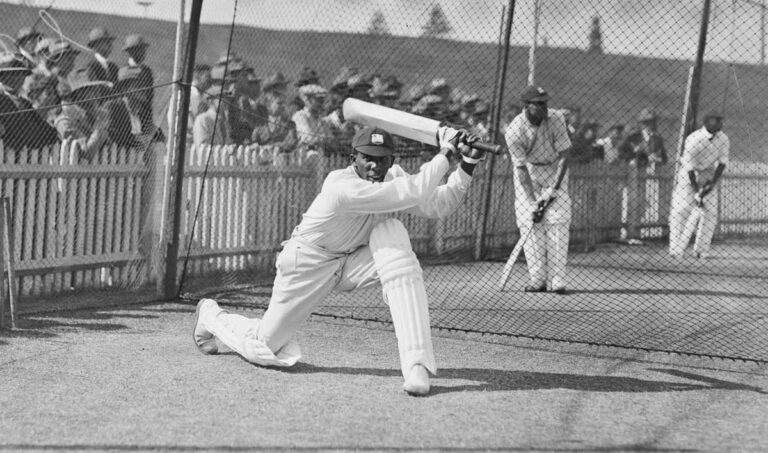

Lord Beginner (Egbert Moore), Victory Test Match (1950)

The second calypso track on our playlist was released in 1950, after the West Indies cricket team triumphed for the first time against the British team in the second of a four-match Test series at Lord’s. The young West Indian cricketers Sonny Ramadhin and Alf Valentine were both only 20 years of age for their debut against the British team. The passenger list for the TSS Golfito, which arrived at Southampton on 10 April, lists five of the cricketers who formed part of the West Indian team including Sonny Ramadhin (see footnote 5).

Cricket had a long history in the Caribbean by the way of British colonialism, whereby enslaved people did the work of bowling at the sons of slave owners in the oppressive heat (see footnote 6). After slavery ended, Black West Indians formed their own clubs and it quickly became the sport of working people. In the 1930s, as people began to organise politically, cricket became enmeshed with the struggle for self-governance, a microcosm of shifting politics on the playing field.

The success of the West Indian team was significant because it showed that the team were capable of battling with the best of British sportsmen, at a time where people were discriminated against based on the colour of their skin. As Learie Constantine, the cricketer and future High Commissioner for Trinidad and Tobago, warned in 1949, ‘There may be some rowdy Tests played in the West Indies in the next few years, unless this colour bar business is brought out in the open and wiped out in the game there once and for all’ (see footnote 7).

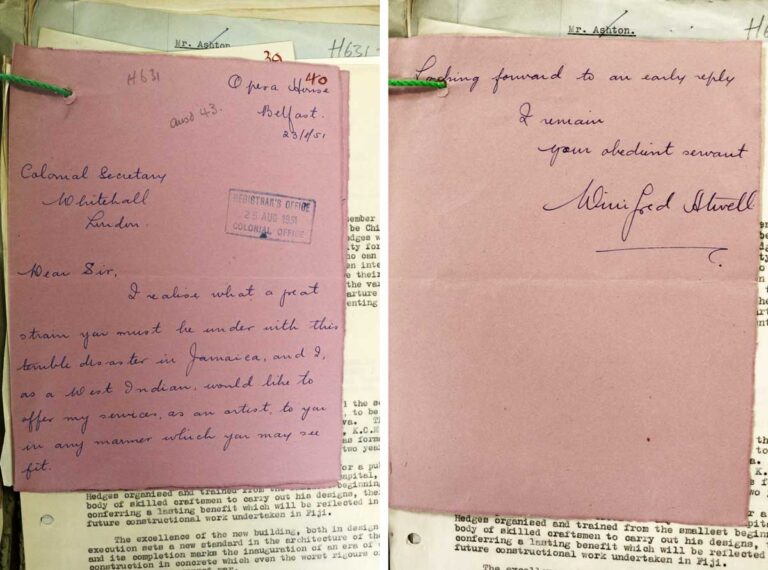

Winifred Atwell, Let’s have another party (1954)

Winifred Atwell’s Let’s Have Another Party was released in 1954 at the peak of big band sound in London. In this track, Atwell’s skills are showcased at the piano – you can imagine the kind of celebratory dancing taking place to this upbeat and joyful piece of music. It was the first song to reach number one in the UK singles chart by a Black artist, and the only one by a female instrumentalist – so far – to do so (see footnote 8).

In the archives we have a letter from Atwell written to the colonial secretary in 1951, regarding the hurricane that hit Jamaica in August of that year, offering her services as an artist. Hurricane Charlie was one of the most destructive ever witnessed on the island, and Atwell writes from the Opera House in Belfast, where we might assume she was performing (see footnote 9).

Janet Kay, Silly Games (1979)

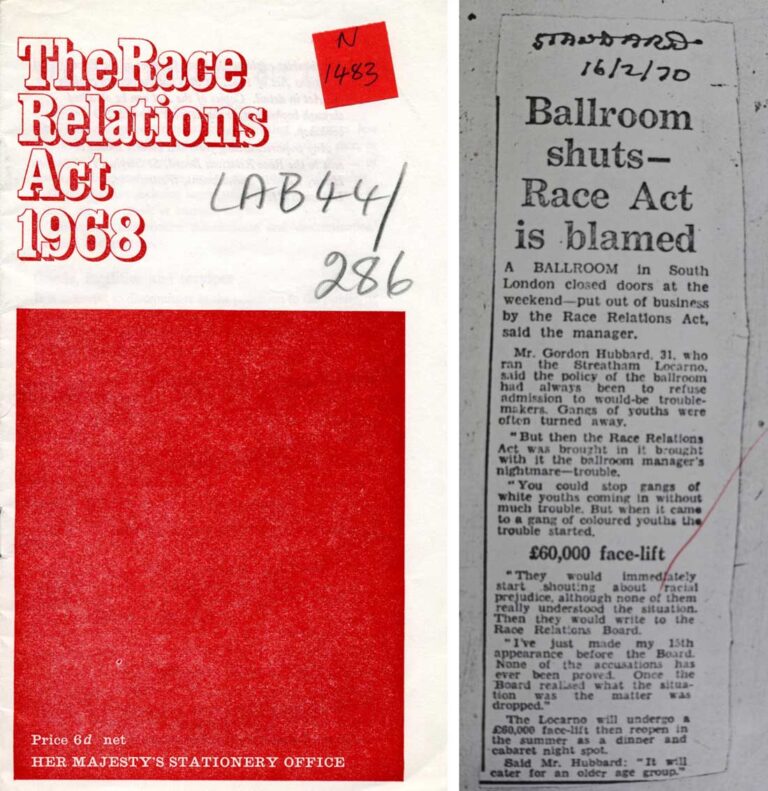

Black arrivals in the post-war period faced discrimination in finding work and accommodation. They also faced being turned away from nightspots.

A genre called Lover’s Rock, most popular in London during the 1970s, was synonymous with the rise of blues parties held in people’s homes. For a small entry fee covering the cost of food, beer and (of course) the trouble of clearing the house of furniture to make way for dancing, people could attend such gatherings. Janet Kay’s Silly Games was part of the genre. Released in 1979, it reached number two in the UK singles chart.

In our collection we hold various records that relate to the colour bar in Britain, from the 1940s to the 1970s, including letters of complaint addressed to the colonial office (see footnote 10). The Race Relations Act of 1968 focused on ending discrimination in housing and employment on the basis of race (see footnote 11). However, in 1970, we see that the decision to close the Locarno Ballroom in Streatham was blamed on the legislation that, according to the Locarno’s proprietors, made it difficult to ‘maintain good order in their dance-halls’ (see footnote 12).

Nonetheless the Race Relations board found people of colour had been unfairly discriminated against on this basis as they tried to access dancehalls. Blues parties provided spaces for people of colour to socialise away from the racist clubbing scene that had existed in Britain for decades.

Linton Kwesi Johnson, Sonny’s Lettah or Anti Sus Poem (1979)

Sonny’s Lettah was also released in 1979, drawing attention to the ‘Suspected Persons’ law, or what came to be known as ‘stop and search’.

The ‘Suspected Persons’ law has its origins in the 19th century and was originally called the ‘Vagrancy Law’. Instituted into law in 1824, section 4 gave police officers the power to act on suspicion:

…every suspected person or reputed thief, frequenting any river, canal, or navigable stream, dock, or basin, or any quay, wharf, or warehouse near or adjoining thereto, or any street, highway, or avenue leading thereto, or any place of public resort, or any avenue leading thereto, or any street, or any highway or any place adjacent to a street or highway; with intent to commit an arrestable offence … shall be deemed a rogue and vagabond…

Section 4, Vagrancy Act 1824

The history of the Vagrancy Act is complex and has been criticised by many as a way for the state to criminalise those at the edges of society, specifically those who are houseless. Yet the law has also targeted suspected witches, palm readers, actors and artists. Section 1 was used to prosecute artists who produced ‘obscene’ works (see footnote 13).

The Working Party of Vagrancy and Street Offences reported in 1976 that the suspected person provision should be repealed and replaced. In February 1979 John Tilley, MP for Lambeth at the time, submitted a petition signed by constituents calling for the immediate repeal of section 4 of the Vagrancy Act and the setting up of an independent enquiry into relations between the Metropolitan Police and the Black community. We have several files in the archive relating to the ‘sus’ law, including HO 287/2728, which includes discussion on the use of the law and attempts to repeal and amend section 4 specifically (see footnote 14).

The law disproportionately targeted young people of colour and led many people to protest throughout the 1970s (see footnote 15). In the poem, Johnson is a character writing to his mother from prison, after he accidentally kills a police officer in defence of his younger brother. The oral tale offers a bleak picture of the relationship between young people of colour and the police in London at the time.

Eddy Grant, Electric Avenue (1981)

Eddy Grant’s second single from his hit album Killer On the Rampage reached the Top 10 in at least a dozen countries, just missing out on the top spot of the US chart in 1983.

The song is a response to what some have referred to as the ‘Brixton riots’ and others the ‘Brixton uprisings’. Between 10 and 12 April 1981, a series of clashes between mainly young people and the Metropolitan Police took place in Brixton, South London.

Intersecting Brixton Road and a short distance south of the Brixton Underground station, Electric Avenue owes its name to the fact that it was the first market street to be lit by electric lights. The history of Electric Avenue has little to do with the content of the song, chosen by Grant because he thought it would make a good title – an instinct that certainly paid off. Grant offers a picture of people struggling to make a living wage and look after their families, referencing the high level of unemployment among the Caribbean immigrant population of Britain at that time.

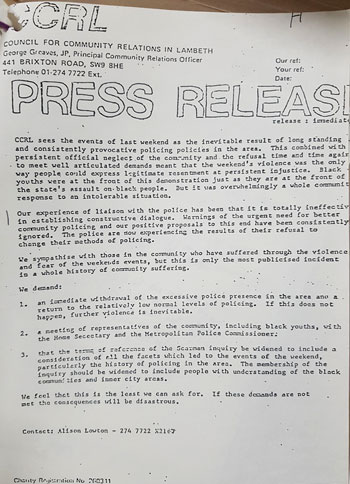

The Scarman Report, produced by the government in the wake of the disturbances, argued that the disorder emerged from social and economic disadvantage. However, community groups such as the Council for Community Relations in Lambeth (CCRL) argued that over-policing and neglect had culminated in the disorder, symptomatic of the lack of trust between the local community and the Metropolitan Police. The CCRL warned that if the police continued to avoid talks with the local community, the situation would only worsen (see footnote 16).

The National Archives holds the records of papers put together for the Scarman report. In HO 266/89 we find several maps which depict the level of damages to property. On this map, green was used to identify properties that been damaged or burgled. The file is particularly focused on prosecuting crime that took place over the weekend.

Stories of celebration and resistance

The influx of music from the Caribbean changed not only the records that people played in their living rooms and on the dancefloor, but how they interacted with each other. Music was a call to political resistance and activism. From Eddy Grant’s anti-apartheid single Gimme Hope Jo’anna, which was banned in South Africa, to Millie Small’s Enoch Power, a response to Enoch Powell’s 1964 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, music can be used to share stories of injustice and call for greater understanding and reform.

Many of the songs on our playlist have been produced at historical junctures in Britain’s past, where ideas about identity, belonging and society were changing. Through listening to these songs, we hear stories of celebration and resistance, only captured partially through records in the archive. As Jeffrey Boakye reminds us, ‘Music has been a gateway to stories I have never lived through and people I have never met.’ (See footnote 17.)

If you were to ‘soundtrack the Windrush’, what would you include on your playlist? Let us know in the comments below.

Footnotes

- Maddy Shaw Roberts, “How the Windrush generation changed British music and arts forever”, 22 June 2020, Classic FM. Access here.

- In the passenger list Aldwyn Robert’s name is spelled ‘Aldwin’. We have used ‘Aldwyn’ in this blog for consistency, as this spelling reflects other writings about the artist. The record does not show an onward address listed for Roberts and we might assume he joined fellow passengers at the Clapham South Shelter.

- Anthony Josephs’ Kitch, published in 2018, chronicles the life story of Lord Kitchener, enmeshing biography with fiction in a musical telling of Kitchener’s life.

- The Canboulay riots are still celebrated in Trinidad. See Raymond Quevedo, Atilla’s Kaiso: A short history of Trinidad Calypso (1983), Jocelyn Guibault, Governing Sound: The cultural politics of Trinidad’s Carnival Musics (University of Chicago Press, 2007) and John Cowley, Carnival, Canboulay and Calypso: Traditions in the Making (2005).

- Catalogue reference: BT 26/1265/91.

- Paul Prescod, “C. L. R. James’ Campaign Against Cricket’s Racial Hierarchy”, Tribune. https://tribunemag.co.uk/2023/01/c-l-r-james-campaign-against-crickets-racial-hierarchy/.

- In 1963, the intellectual CLR James published one of the leading texts on cricket, Beyond a Boundary, describing racial and class tensions that found expression in various cricket clubs – the book is considered one of the foremost texts on cricket ever produced.

- Tom Horton, “Black plaque honouring pianist Winifred Atwell unveiled in south London”, 6 November 2020, Belfast Telegraph. Access here.

- There are other letters of support in CO 137/900/1 including one from the Bata shoe company, based in Tilbury, pledging the provision of shoes to be sent over to the island, and birdsong maestro Ludwig Koch, who proposes a birdsong concert to raise funds to repair the storm damage.

- Catalogue reference: LAB 26/55.

- The Race Relations Act of 1965 made it a civil offence to refuse to serve a person, to serve someone with unreasonable delay, or to overcharge, on the grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins.

- Catalogue reference: CK 2/238.

- In 1929, DH Lawrence was prosecuted under the act for the display of ‘obscene’ artwork.

- The Black Cultural Archives (BCA) holds records of the ‘Scrap SUS’ campaign, including a report entitled, ‘Let the police be accountable: Evidence and Recommendations to the Inquiry into Community/Police Relations in Lambeth.’

- Shaku Yesufu (2013), “Discriminatory Use of Police Stop-and-Search Powers in London, UK”, International Journal of Police Science & Management, 15(4), 281–293.

- The records of The Brixton Defence Campaign are held at BCA in Brixton, and offer insight into the events of April 1981 in Brixton from a non-government perspective.

- Jeffrey Boakye, Musical Truth: A Musical History of Modern Black Britain in 25 Songs (Faber & Faber, 2021).