Howard Carter in King Tutankhamun's tomb. Harry Burton, copyright expired

My colleagues are already tired of my obsession with Ancient Egypt, but today at least, I have an excellent reason to raise the subject again.

75 years ago, on 2 March 1939, Howard Carter died in relative anonymity; today, outside of the rather restricted egyptological circle, his name raises more eyebrows than enthusiastic comments. And yet, in 1922, he made a discovery that echoed down the corridors of archaeology, THE discovery – the virtually intact tomb of Tutankhamun. Incidentally, 1922 was also the year during which independence was unilaterally bestowed upon Egypt by Great Britain, which inextricably linked Egyptology to politics.

The Valley of the Kings in 1922. PRO 30/69/944

It all started in the Valley of the Kings… This is, of course, a place full of magic, evocative of ancient mysteries and riches – and, as one of my colleagues pointed out not too long ago, of peripatetic mummies out of bad American films! Yet, it is also difficult to find a more remote, barren, scorching hot, unpleasant locality.

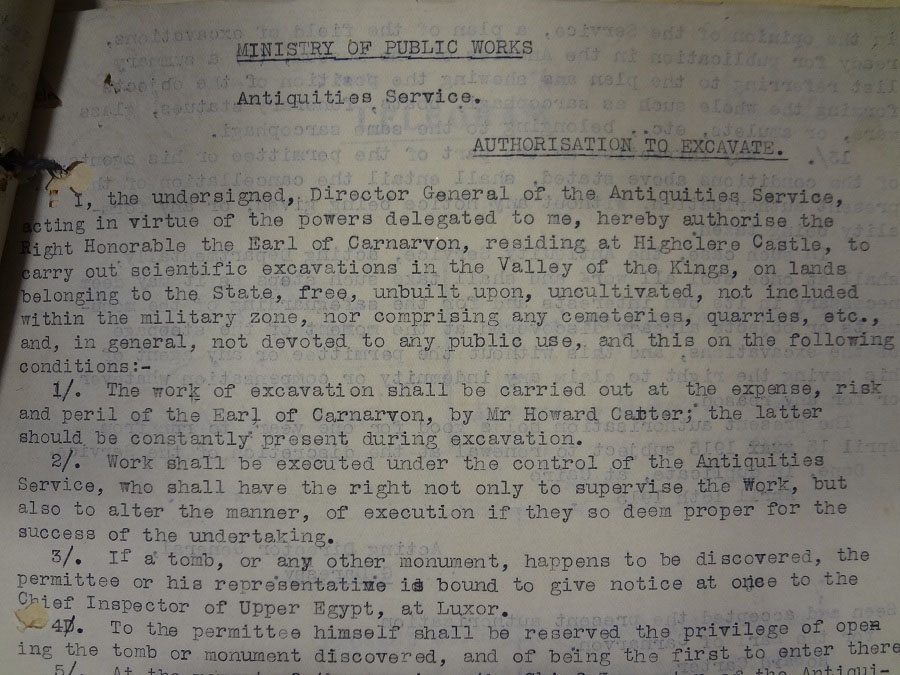

Authorisation to excavate in the Valley of the Kings, 1915. FO 141/483

Howard Carter and his sponsor, George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon were given permission to dig in the Valley of the Kings in 1915.

Carter went through a series of rather frustrating, fruitless seasons until he could finally write in his diary, held at the Griffith Institute , “entrance of tomb of [blank]

In bed rock floor of water-source (below entrance of Ramses VI). Discovered 4th November 1922.”

On 6 November, he sent one of the most famous telegrams in (egyptological!) history: “At last have made wonderful discovery in the Valley. A magnificent tomb with seals intact. Recovered same for your arrival. Congratulations. Carter.”

It would take Howard Carter and his team about 10 years to excavate the tomb entirely; for the sake of scientific accuracy and caution, obviously, but also because a wave of Tutmania swept the entire planet, firing the imagination of the world, reviving centuries of endemic hostility between France and Great Britain on the banks of the Nile, and fuelling nationalist discontent.

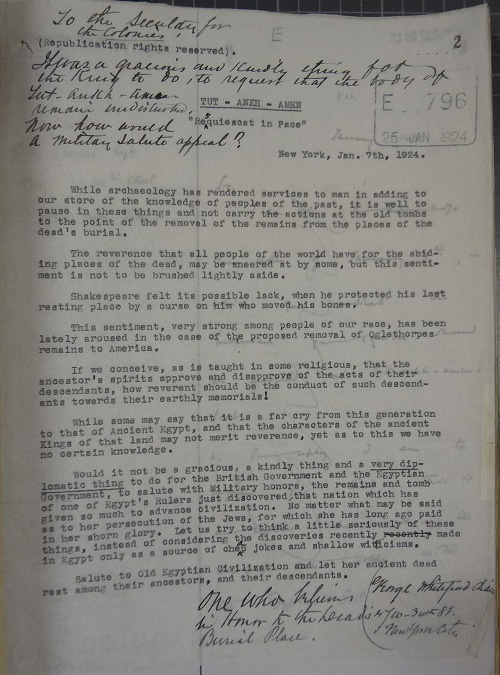

"Would it not be a gracious, a kindly thing and a very diplomatic thing to do for the British Government and the Egyptian Government, to salute with Military honors, the remains and tomb of one of Egypt's Rulers just discovered" FO 371/7733

Carter had to contend with a constant stream of visitors (some applications can be found in FO 371/7733 and FO 141/483/1), many of whom were stimulated by a kind of morbid curiosity partly fostered by the rumours of an ancient curse leading to the death of anyone getting too close to Pharaoh. I’m sorry I’ll have to disappoint you there – Admittedly, Lord Carnarvon died on 5 April 1923 in the Continental Hotel in Cairo (the lights flickered, they said, his hound in Highclere Castle howled at the precise moment of his death…), but curses were, at best, infrequent in Ancient Egypt and one cannot help but notice that Carter died many, many years after having disturbed Tut’s rest. Everyone, however, is sensitive to the fantastic, and the tomb of Tutankhamun became the focus of esoteric theories and very strange suggestions such as this one, from an American: ‘Would it not be a gracious, a kindly thing and a very diplomatic thing to do for the British Government and the Egyptian Government, to salute with Military honors, the remains and tomb of one of Egypt’s Rulers just discovered’ FO 371/7733.

The Eastern Department of the Foreign Office dismissed it with a casual “external evidence would point out to his being the possessor of a weak mind,” but it’s a good example of what Carter and his team had to deal with.

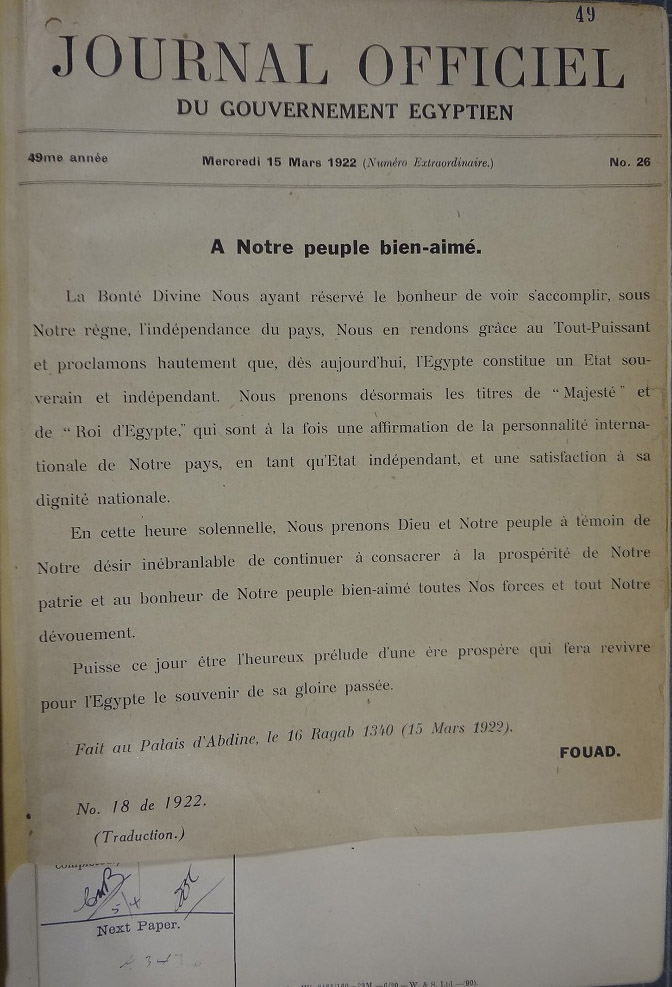

King Fuad's message to the Egyptian nation, 1922. FO 371/7733

Intrusive tourists, though, were probably not as annoying as the interference from the director of the Antiquities Service, Pierre Lacau.

When France and Britain had signed the Entente cordiale in 1904, it had indeed been determined that “the post of Director-General of Antiquities in Egypt shall continue, as in the past, to be entrusted to a French savant”; Egyptology therefore remained a French prerogative, a prerogative Lacau was not ready to let go. Tutankhamun portrayed to the French the image of an egyptological scene on which, suddenly, the British took the lead role, of a science which, unexpectedly, had ceased to be French. Lacau, without actually doing anything against Carter, certainly didn’t help, and proved inflexible in his conviction that the treasure as a whole should remain in Egypt. Carter, who had a reputation for being quick-tempered and petulant, proved just as inflexible in his conviction that Lady Carnarvon should at the very least get financial compensation.

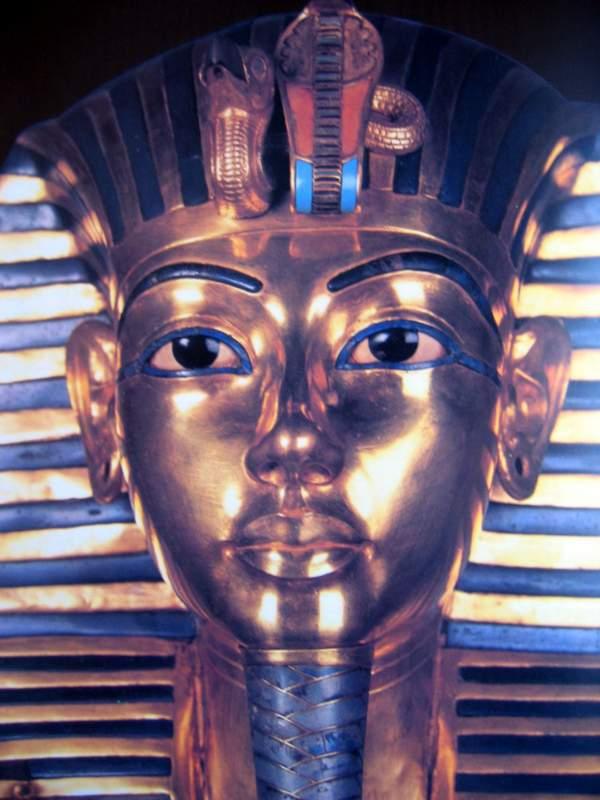

Tutankhamun death mask. Juliette Desplat

Unfortunately for Carter, Lacau was backed by the young, nationalist Egyptian government, eager to extricate Egypt from a European imperialism which had reached as far as the remnants of its ancient history. In February 1922, Lord Allenby, High Commissioner in Egypt, had sent Sultan Fuad a Declaration to Egypt stating: “The British protectorate over Egypt is terminated, and Egypt is declared to be an independent sovereign state”. In March, the Sultan had been proclaimed King under the name of Fuad I. In his message to the nation, the King wished that the constitutional change might be seen as “the promising start of a prosperous era which shall restore to Egypt the memory of her glorious past”.

Immediately adopted, Tutankhamun, representative of the power and magic of Ancient Egypt, a symbol of geographical consistency and historical continuity, crystallised the hopes of a nation which found it difficult to keep pace with its new status. As recounted in the Foreign Office file, which I can only urge you to read as it’s better than any Kafkaesque story, Carter and Carnarvon had made a major political blunder by giving an exclusive to The Times, and the Egyptian Minister of Public Works did his best to drive him away from the tomb. Things went so far that Carter closed the tomb altogether in February 1924, which proved another error of judgement, not only because he chose to ignore the change in Egyptian politics, but also because he had left the upper part of the sarcophagus dangling at the end of ropes which might have snapped. Lacau seized the tomb on behalf of the Egyptian Government.

So, whatever some people might think, there was more to Carter’s story than an archaeologist hitting gold… I wonder what Tutankhamun would have made of the political intrigue and squabbling over the discovery of his tomb… Most likely he’d have shrugged and said those words engraved on the wall of his golden shrine, I have seen yesterday, I know tomorrow…

I have to assume when you talk of “peripatetic mummies out of bad American films” you are not referring to the very splendid 1932 film “The Mummy” with Karloff, which is very far from a *bad* film – even though it may not be too historically accurate!

Of course not, how could I?! (Although I have a marked preference for Fisher’s 1959 film!)

The political aspects are always interesting, not least the views of Britain and France that they could dig-up and take away (obelisks come to mind) what they wanted, the issues of mummies are still hotly disputed over who should own them. There are of course two sides to the story and the discovery of Tutankhamun has led to serious problems in the tomb with conservation issues. Whilst Carter’s discovery was a great discovery it does raise the issue of the right to have dug there and nowadays (rightly) the Egyptian Government would need to give their consent and strict guidelines on what archaeologists can and cannot do. To give The Times an exclusive should be viewed in The Times and its role in British journalism at the time.

It is entirely true that France and Britain, especially France, had established a long-lasting ‘archaeological protectorate’ over Egypt. To be fair, however, the London obelisk was a gift from Muhammad Ali to the UK to commemorate the battles of the Nile and of Alexandria, just as the obelisk now standing Place de la Concorde in Paris was presented by the Egyptian ruler to King Louis-Philippe in 1826…

Carnarvon and Carter did have a legal right to dig in the Valley of the Kings; the 1915 contract granting authorisation to excavate stated that “work shall be executed under the control of the Antiquities Service, who shall have the right not only to supervise the work, but also to alter the manner of execution if they so deem proper for the success of the undertaking,” keeping the excavators firmly under the thumb of the Egyptian Government… It was quite clear as to what they could or could not do.

The exclusive given to the Times was signed to avoid constant interruptions and work slowdowns, and modelled on the exclusive granted to the same newspaper by the Royal Geographical Society during the 1921 Everest Expedition. The Times got the exclusive for £5,000 and 75% of the profits made from the sale of articles and photographs to other newspapers – which was meant to help finance the excavation of the tomb. I am not entirely sure why The Times was selected (highest bidder?), but it was perfectly sensible from a financial, logistical point of view… But, as I said, it was a huge political mistake; when the Times correspondent, Arthur Merton, was officially made a member of the excavation team in October 1923 in order to deflect criticism, it was too late – Carnarvon and Carter had chosen to ignore the imperialist context in which Egyptology had developed, and had been unable (or unwilling) to understand that it would have been vital to discard this pre-war attitude deeply rooted in outdated notions of colonialism, elitism, and ‘scientific privilege’. It is, however, always rather easy to talk with the benefit of hindsight…

My point about France and Britain’s actions (one could add Germany to the list) was the ‘Colonalism’ that was prevalent and which in Britain’s case didn’t end in the 1920s but to the 1950s vis-à-vis the Dead Sea Scrolls. One has to look at the enlightened ways that archaeology in the Valley of the Kings including KV64 is carried out. I wonder how we would feel about ‘giving’ the Romans Stonehenge or similar for their victories?.

Thanks for your article.

I was always interested in Egyptian History but never been educated in that field. While reading your blog, I was intrigued to know the hieroglyphs of my favourite quote; “I have seen yesterday, I know tomorrow” I would appreciate if you can teach me the images of this quote.

Thanks from Steve