‘Complexion here was an ashed blueish grey, the expression most anxious and distressed with the eye-balls staring, and the lids half closed. Respiration was extremely laboured and noisy with frequent efforts to expel copious amounts of tenacious yellowish green frothy fluid which threatened to drown them, and through which they inhaled and exhaled air into and out of their lungs with a gurgling noise.’ [ref]1. Director of Gas Services, France – File 1 (catalogue reference: WO 142/99)[/ref]

This distressing statement comes from Captain Edward L Reid of the Royal Army Medical Corps, serving with No. 7 Field Ambulance in May 1916. Reid is describing just some of the horrific sufferings experienced by soldiers with gas poisoning during the First World War. As part of our ongoing medical technology series of blogs, today’s post will examine some of the earliest developments made by the British Army in 1915 to try and combat the dangers posed by this new weapon.

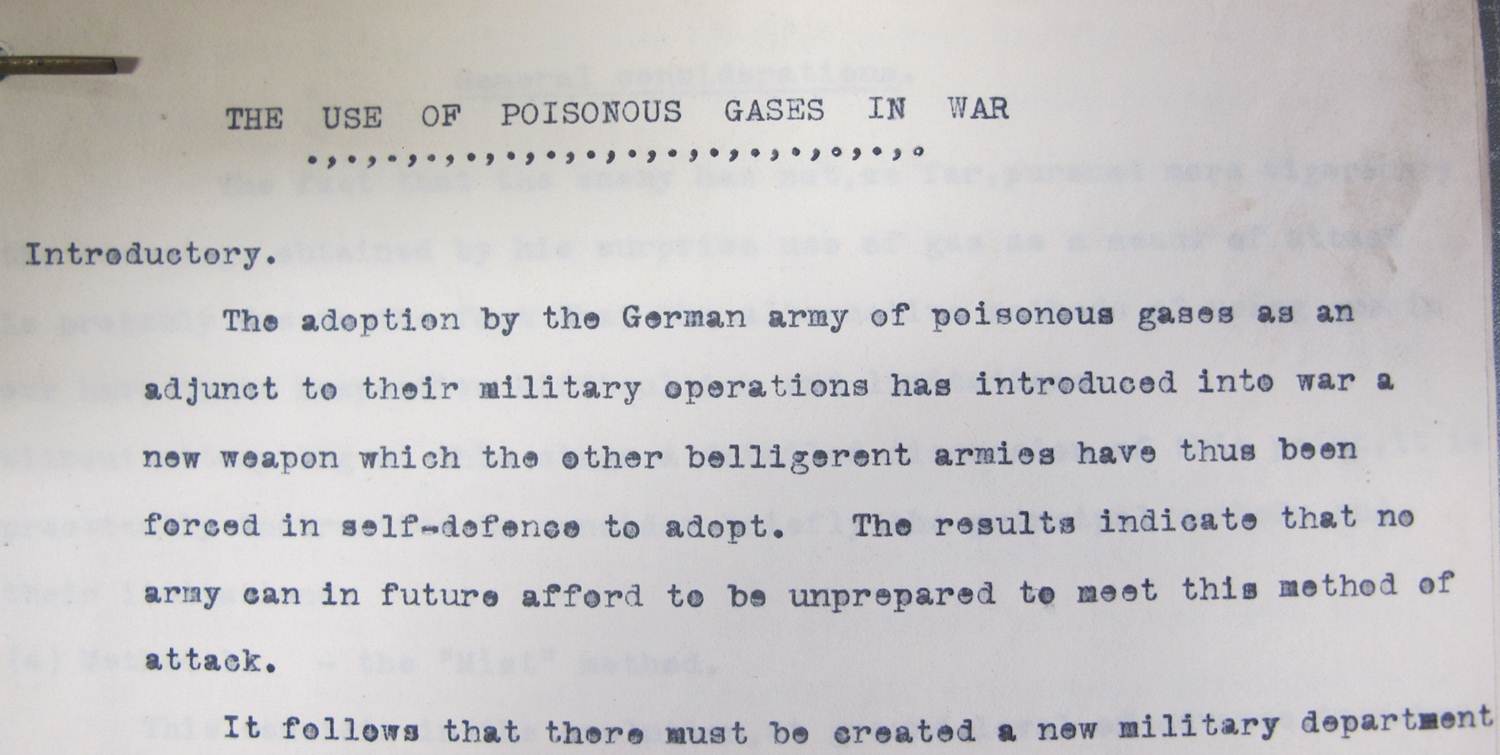

Opening paragraph from The Use of Poisonous Gases in War report made by the Royal Army Medical College in June 1915 (catalogue reference: WO 142/183)

Within the Chemical Warfare Department series in WO 142, you can find a subseries of papers titled Anti-Gas files. Within file 4, there’s a report titled ‘The Use of Poisonous Gases in War’ from June 1915. The report describes five essential requirements of any gas protection device for troops:

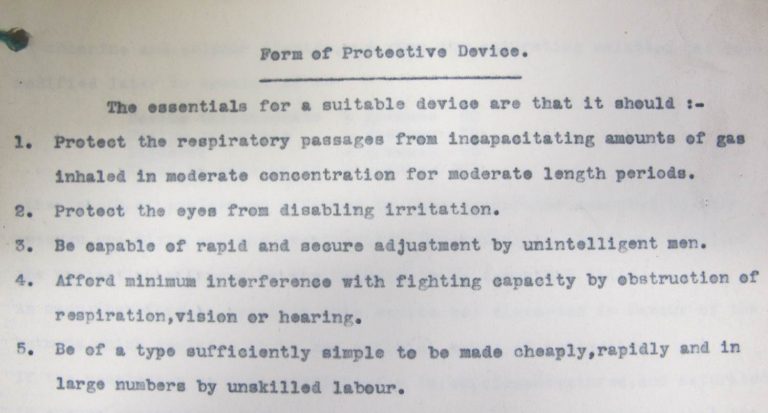

‘1. Protect the respiratory passages from incapacitating amounts of gas inhaled in moderate concentration for moderate length periods.

2. Protect the eyes from disabling irritation.

3. Be capable of rapid and secure adjustment by unintelligent men.

4. Afford minimum interference with fighting capacity by obstruction of respiration, vision or hearing.

5. Be of a type sufficiently simple to be made cheaply, rapidly and in large numbers by unskilled labour.’

Essential requirements of new gas protection devices stated in the June report (catalogue reference: WO 142/183)

The initial respiratory protection is described quite plainly as ‘a pad of cotton waste wrapped in black veiling’ which was ‘approximately the size of a hand’. Folds were included so to offer protection of the eyes, as were anti-gas goggles. This pad was to be dipped in a solution that would absorb the gas being used by the enemy (chlorine). Unfortunately, it was found that when using this pad, men were ‘incapacitated’ within five minutes by respiratory and eye irritation, at a time when the Army Medical Service was seeking protection for at least 20 minutes. Consequently, the report confirms that the cotton pad failed to comply with the first four of the above essential requirements. [ref]2. Anti-Gas Department, London – File 4 (catalogue reference: WO 142/183)[/ref]

Developments led initially to a face mask made of textile with a fitted pad opposite the mouth. Celluloid eye pieces were incorporated with purse string elastic to provide adjustment over the forehead and under the chin, with an elastic band to fit over the back of one’s head. This face mask idea quickly moved towards a full helmet based respirator design, which was introduced in May 1915. The RAMC report continues:

‘The helmet consisted of textile, the two or later three pieces of which were securely sewn together by a single seam of cotton thread, a celluloid window being inserted in the situation of the eyes. It was large enough to fit over the service cap and come well down over the shoulders, the skirt being tucked beneath the collar of the tunic or shirt which is then buttoned over it. The external surface was 3¼ square feet.’

Developments from the initial pad design led to a textile helmet that covered the whole head. © IWM (EQU 3913)

Despite fears of possible asphyxiation by carbon dioxide exhaled by the wearer of the helmet, early tests showed men could remain in their helmet for three hours in an atmosphere containing gas, as well as being able to run ‘a quarter of a mile with the helmet securely adjusted’.

By September 1915, the British Army felt ready to launch their first gas attack as part of the Battle of Loos. Using the experiences of the 15 Infantry Division and 46 Infantry Brigade, however, we can clearly see the tragic difficulties when deploying new weapons and protective devices in combat situations.

The War Diary of the 46 Infantry Brigade Headquarters reveals ‘misgivings’ as to whether the wind strength was sufficient to push the British gas towards the German positions on the morning on the 25 September, the opening day of the battle. Subsequently, ‘a considerable number’ of British troops are noted as having been gassed by their own gas as they assaulted the German lines.[ref]3. Catalogue reference: WO 95/1948/1[/ref]

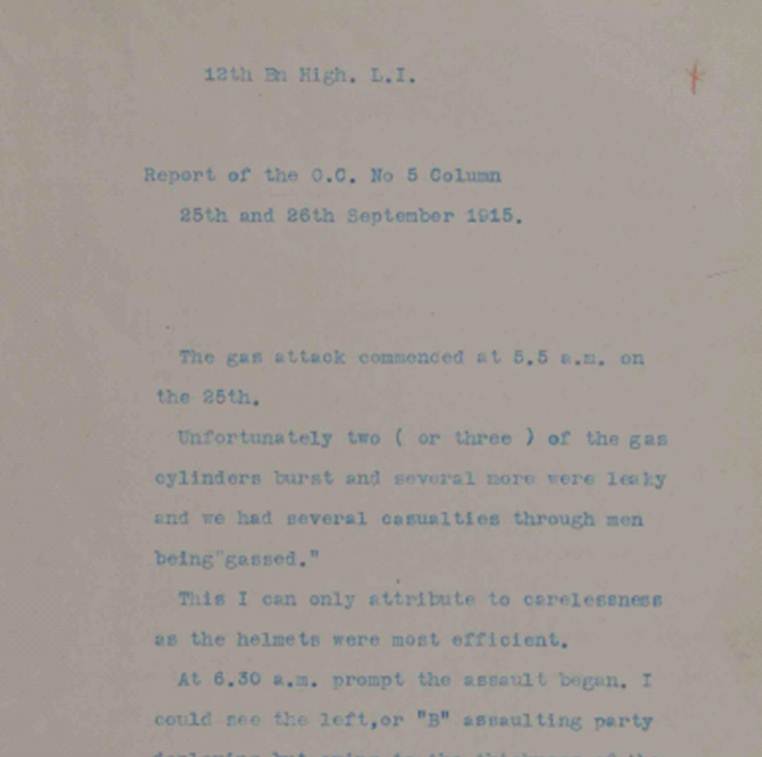

The 12 Highland Light Infantry was one such Battalion affected by unsuitable wind conditions. Lieutenant Colonel J H Purvis, commanding the Battalion, reported that ‘many of A Company’s men suffered from the effects of our own gas before leaving the trenches’. Captain P W Torrance elaborates further, revealing that ‘two (or three) of the gas cylinders burst and several more were leaky’ resulting in many gas casualties before the attack had even been launched.[ref]4. catalogue reference: WO 95/1952/2[/ref]

Report from Captain Torrance, 12 Battalion Highland Light Infantry (catalogue reference: WO 95/1952/2)

While Captain Torrance blames carelessness of the soldiers for the primary reason for suffering gas poisoning as the offensive began, The Official History records some of the practical difficulties experienced on the 25 September. Firstly, the early morning rain caused the protective chemicals that the helmets had been soaked in to ‘soak out and irritate the eyes’ of the troops. For others breathing became difficult when advancing towards the enemy, resulting in ‘many men’ removing their helmets and subsequently suffering the effects of gas poisoning as a result.[ref]5. Brigadier-General Sir James E. Edmonds, Official History of the War: Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915 (MacMillan and Co., Limited, London, 1928) p. 173 and p. 194[/ref]

So, again we see a continuing pattern of the First World War initiating new weapons, which leads to new protective measures or medical technologies to aid people caught up in the conflict. In the case of gas protection, such designs came to rely more heavily, at least initially, on battlefield exposure rather than by extensive laboratory testing. While protective gas respirators became more sophisticated and consistent as the war progressed, unfortunately for some, as the events at Loos 100 years ago show and as the opening statement vividly reveals, sometimes medical protection can only go so far in modern warfare.

With thanks to The Imperial War Museum for use of the two gas mask photographs included in this blog. Researchers should search the Imperial War Museum collections website to see further gas mask and helmet developments during the First World War.

When was gas first used against British troops on the western front?

Hello Neil, thank you for your question and for reading the blog.

German forces were the first to use Gas during the Second Battle of Ypres on 22 April 1915 against French and French colonial troops. Further Gas attacks were made on the 24 April against Canadian troops and then again on British troops, I believe, on 2 and 5 May 1915.

If you can get hold of a copy of the Official History, this will give a much more thorough account of impact and casualty numbers.

Hope this helps,

David

Thanks for your reply!

My Great-Grandfather served with 5th Black Watch that took part in the battle of Neuve-Chapelle in March/April 1915.

I wondered if gas was used during that battle but it doesn’t sound like that was the case.

Neil

Where can I see a copy of the Official History of battles in the Neuve-Chapelle area? Do I have to go to the Museum in London?

Dear Mrs Haston,

Thank you for your comment and for reading through the blog. I hope you found it informative.

Copies of the Official History can be consulted or requested via most library services, so I would start with your local library for initial advice regarding availability.

The National Archives does have copies available via our on-site library but these are for reference only and cannot be loaned out. If you do decide to visit us to consult these volumes, please check our opening times and Library catalouge for further information.

I hope this helps,

David

Please can you advise as to whether gas was used against the British and/or commonwealth armies in Egypt and Palestine between 1916 and late 1918. My father served with the R.O.D branch of the Royal Engineers during this period, and he had always stated that his lung condition from which he suffered, and ultimately died, was a result of a gas attack.

His army medical records show clearly that he was treated at a casualty clearing station and spent a further four weeks in a hospital, but the actual cause of ‘injury’ that is recorded, relates to ‘chest’ and ‘breathing’ – not very explicit!

Upon his discharge, he was awarded a disability pension, but for a period of five years only, this indicating to me that it was unlikely to be a life-long condition.

I am unable to find any reference to gas being used by the Turkish or German armies in this theater of the war in my research to date.

I would be extremely grateful if you are able to help me – thank you.

Hi Alan,

Thank you for your comment.

Please can you use our online contact form to send this enquiry to us? This way we can give a much more detailed reply than what is available on the blog comment option.

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/contactform.asp?id=1

Do mark it for my attention and I will endevaour to come back to you as swiftly as possible with details of how to follow-up with your research.

Many thanks,

David

What happened to the 11th Batt. the Borders in 1916?

My Grandfather Henry Fenner saw the results and horrors of gas attacks. In a document he signed himself off as

Henry Fenner C.2.M.S. Anti Gas Estab. R.E. He was a volunteer testing gas masks of various designs and was once pulled out of the test room following the failure of a mask.

My Grandma said the gas used Smelt like Peardrops. She met my Grandad at the Anti gas Establishment.

Sorry following yesterdays posting I got a magnifying glass and where I inserted M is incorrect. There fore his sign off should read.

Henry Fenner C.2.In.S. Anti Gas Estab. R.E.

I’m not sure if I’ve interpreted this correctly but I think it is.

Henry Fenner Corporal. 2nd. Infantry. Sapper. Anti Gas Establishment. Royal Engineers.

Would this be a correct interpretation?

[…] In another distressing report, preserved in the United Kingdom’s National Archives, a British soldier in the Royal Army Medical Corps described survivors of a poison gas […]