Many of the records held at The National Archives that relate to the presence of Black and Asian people in Britain are here because of the over-policing and surveillance of these communities.

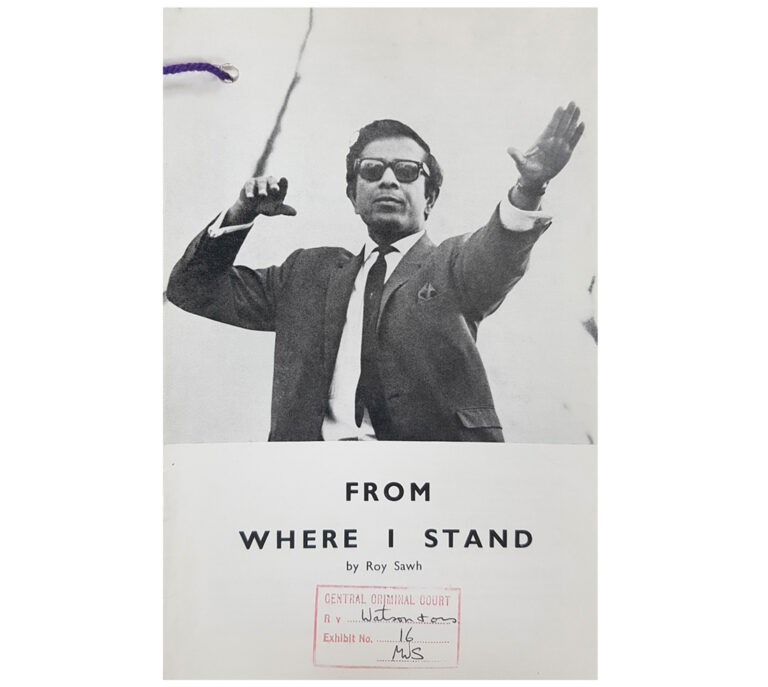

This is certainly the case with the focus of this blog, From Where I Stand, a pamphlet produced by Guyana-born civil rights activist, Roy Sawh, who sadly passed away in Spring, 2023. The document is contained within the file CRIM 1/4777, with CRIM standing for records of the Central Criminal Court.

Sawh was an experienced speaker at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park, London, a traditional site for public speeches and debates since the mid-18th century. In the pamphlet, Sawh sought to make, ‘the main points of the speech I should make but never do’, as a result of getting side-tracked by questions.

Beginning with the opening line, ‘Hello comrades and friends, ladies and gentlemen, and all hecklers and racists…’ Roy was acutely aware that there were many in the crowd with less than noble intentions towards him. These included, as Perry Blankson (2021) has shown, ‘Special Branch officers of the Metropolitan Police taking careful notes’, which would then be used to prosecute Sawh for ‘incitement to racial hatred,’ under the 1965 Race Relations Act. The evidence gathered against him and three other speakers (which, in the context of the well-documented police racism at the time, must be read with a critical eye (cf. Waters, 2019, pp.93-124)), forms the basis of much of the file held at The National Archives.

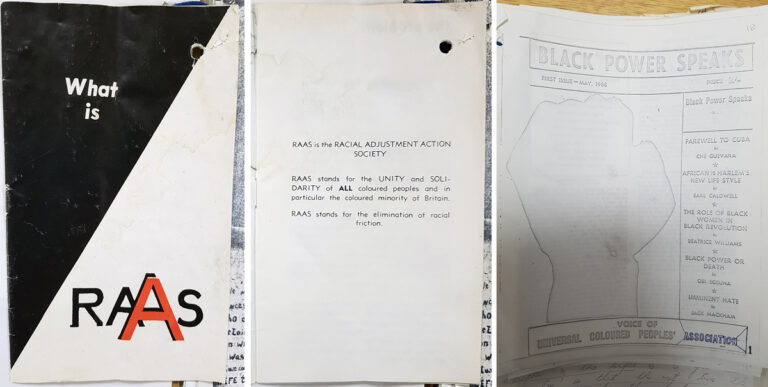

It is also worth noting that a number of other similar pamphlets and campaign material produced by Black and Asian activists, in the post-war period and before, exist at The National Archives for the above-mentioned reason. These include pamphlets produced by RAAS: The Racial Action Adjustment Society, founded by Trinidadian Michael X[ref]John Williams (2008: 115) explains the name: ‘Raas (short for raasclaat = arse cloth = sanitary towel) is a popular Jamaican obscenity, but one that would have been unfamiliar to white people. The point of the name was to make fun of the white media, getting them to talk about Raas all the time.’[/ref], and the Universal Coloured People’s Association (UCPA), founded by Nigerian Obi Egbuna. As a testimony to the ideals of political blackness of the time, Sawh was involved in both organisations.[ref]Political blackness loosely refers to the politics of solidarity between African, Caribbean and Asian communities, which arose during the 1960s and 1970s, and were fostered by the communities’ shared structural position in society.[/ref]

Sawh’s background

Born on a sugar estate in Uitvlugt, Guyana, 1934, Roy was descended from Indian indentured labourers. His father was a sugar estate worker who was brought to the colony at the end of the nineteenth century, and his mother was second generation Guyanese.[ref]The National Archives guide to Indian Indentured Labourers provides more information about researching this topic at TNA.[/ref]

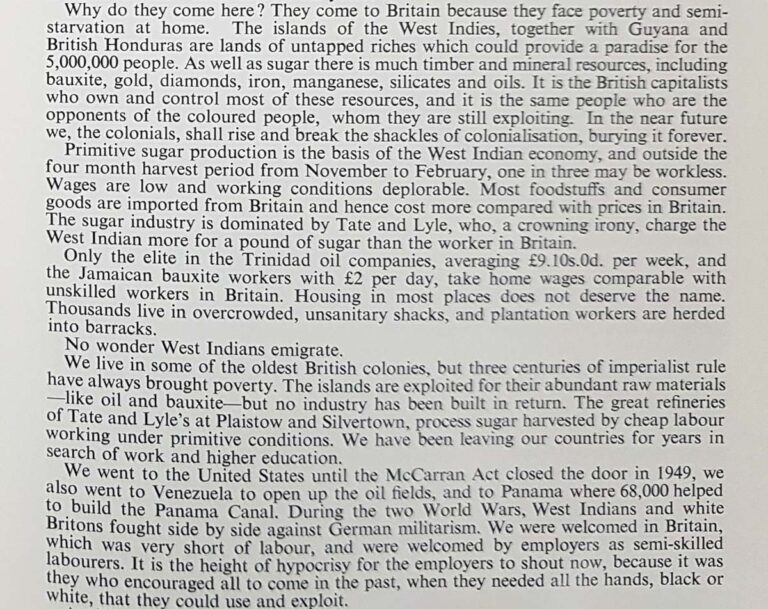

In From Where I Stand, Sawh speaks in detail about the abject poverty in colonial Guyana that formed the backdrop of his childhood and led him and many others to migrate:

‘They come to Britain because they face poverty and semi-starvation at home.’

Images of sugar estates at Uitvlugt as well as elsewhere are also captured in Colonial Office records held at The National Archives.

Life in Britain

Sawh arrived in Britain in 1958 with the intention to: ‘soon return to Guyana a rich man and relieve his mother once and for all of the continual anxiety of where the next slice of bread would come from’.[ref]Roy Sawh (1987), Roy Sawh: From Where I Stand London: Hansib. Page 25[/ref]

Describing himself as ‘all-cock-a-hoop’ about coming to the ‘mother-country,’[ref]Roy Sawh (1987), Roy Sawh: From Where I Stand London: Hansib. Page 24[/ref]Roy was by his own admission ‘very naïve politically’ in Guyana but would experience a number of racist incidents, which would come to shape his worldview. One such incident is recounted in a later text[ref]Roy Sawh (1987), Roy Sawh: From Where I Stand London: Hansib. Page 26[/ref]:

He was very happy as a bus conductor. So happy that he took a picture of himself and sent it home to his mother to show her that he was trying to establish himself. The pay was good and he calculated that with about £13 per week he would soon return to Uitvlugt a rich man. But things did not work out as planned. The second week on the buses an elderly white women spat in his face and called him a ‘black bastard’. He pushed her and had practically the whole bus at his neck. ‘That was the end of my association with London Transport. I resigned in disgust.’

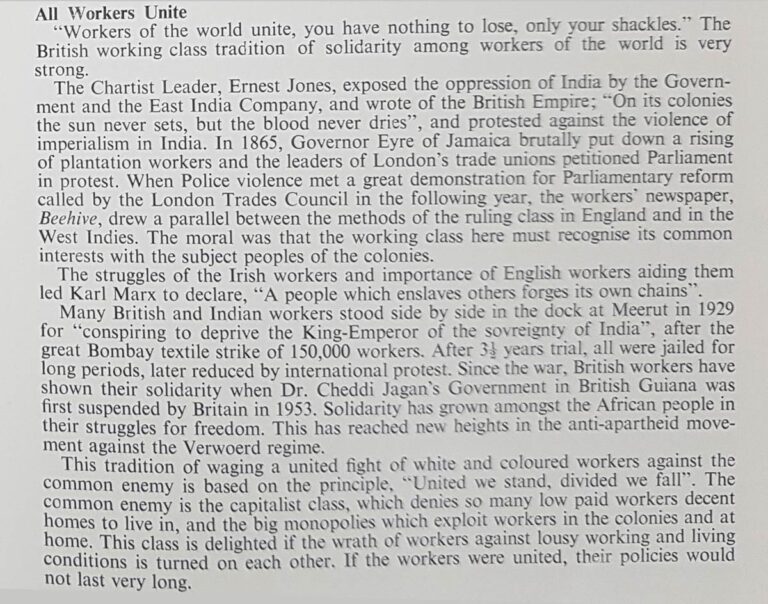

In spite of such experiences of racism, Sawh expresses a Marxist view of race in the pamphlet, which certainly chimes with the arguments of writers such as A Sivanandan[ref]For Sivanandan (1983: 104), capital prevents, ‘the horizontal conflict of classes through the vertical integration of race – and, in the process, exploits both race and class at once.’[/ref]:

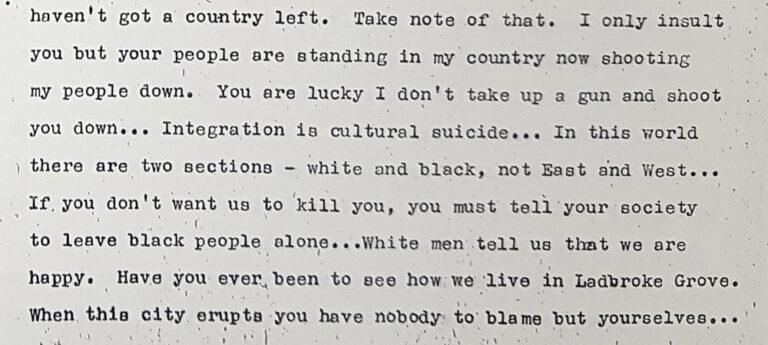

With calls for ‘workers of the world [to] unite’ and his identification of the ‘capitalist class’ as ‘common enemy’, ‘delighted if the wrath of workers … is turned on each other’, his pamphlet is certainly at odds with his alleged views as recorded by the police, who ascribe to him a much more reductive world view, where there ‘are two sections – white and black’:

Race Relations Act

In 1967, Sawh was put on trial under The Race Relations Act and jailed for eight months. The police notes record anti-Semitic as well as anti-Irish racism, misogynistic views of white women, homophobia, as well as calls for violent retribution against white society, with white people described in various pejorative terms throughout.

These notes, again, conflict with much of the content of his pamphlet, which for instance carries strong condemnations of the Mosley Union Movement’s ‘crude anti-Semitic material’, supportive references to the ‘struggles of the Irish workers’ and other colonised peoples, a statement about how he ‘welcome[s] the idea of inter-marriage’ , and as previously noted calls for solidarity with the white working class. The pamphlet doesn’t mention homosexuality.

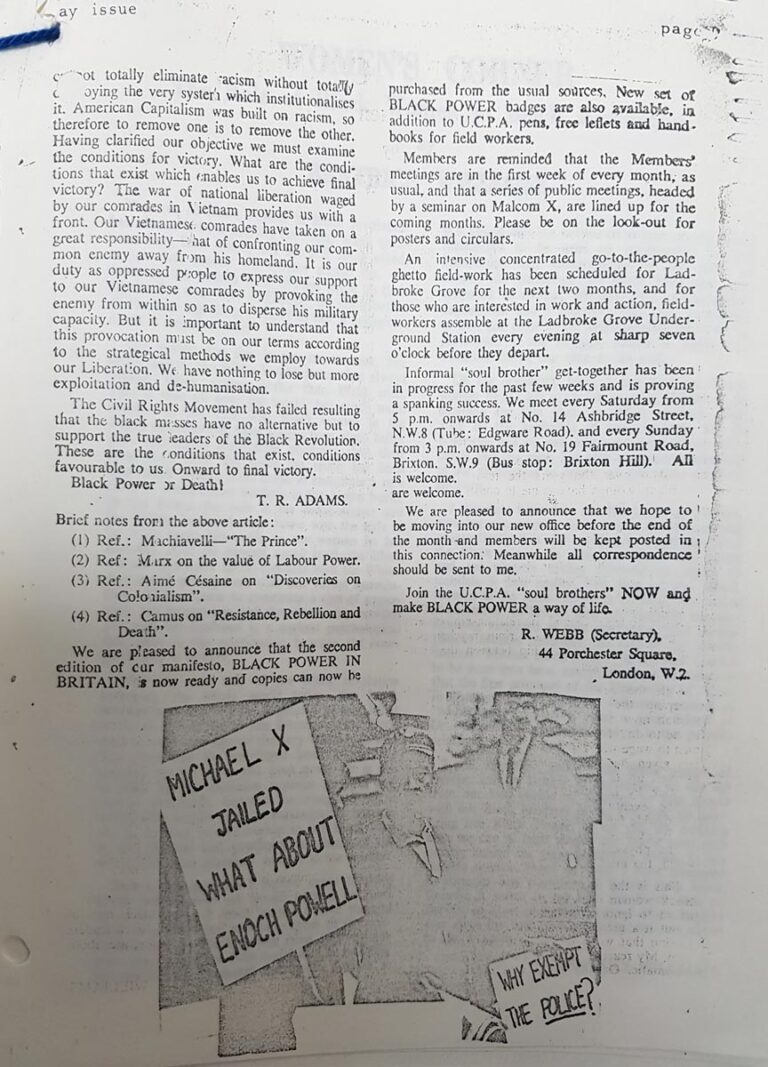

The evident contradictions in the file raise questions about both Sawh and the Police.[ref]Three years later in 1970, The Mangrove Nine trial would force the first judicial acknowledgement that there was ‘evidence of racial hatred’ in the Metropolitan Police (See footnote 2).[/ref] They highlight one of the criticisms of The Race Relations Acts that, as Robin Bunce (2017) describes it: ‘The government used the new Race Relations Act as a weapon against Black Power.'[ref]Jenny Bourne (2015: 21) elaborates on a further criticism of the Act: ‘…every race relations act presaged a new immigration control act. The government of the day could on the one hand appear to be non-discriminatory when bringing in immigration controls, by emphasising its willingness to work for the integration of those already here, while on the other hand ignoring the fact that those same immigration controls, directed specifically at New Commonwealth immigrants (i.e. ‘darker’ people), were enshrining discrimination in statute.'[/ref] This is brought out strongly in another The National Archives record from the UCPA’s Black Power Speaks magazine, which protests the prosecution of RAAS founder Michael X under the Act but not Enoch Powell.[ref]The second placard, ‘Why exempt the police?’ draws attention to the important issue of power. Clearly, black prejudice, however toxic, wasn’t supported by the apparatus of the state (the criminal justice system, education system, media, and so forth), making it very different to white racism.[/ref]

It’s also of note that this document can be found in another court file, this time prosecuting Obi Egbuna the founder of the UCPA, again, under the Race Relations Act.

As the official archive of the UK government, The National Archives’ records largely represent the perspective of the state. The inclusion of records such as Roy Sawh’s From Where I Stand, as well as What is RAAS and Black Power Speaks, highlights that there are nonetheless important and rare documents expressing community voices, which often challenge state narratives, contained within them as well.

These files along with countless others can be ordered and viewed at The National Archives. It’s also important to note that these pamphlets – like many others – are not included in the file’s catalogue description. Thus, researchers are advised to perform broad keyword searches around areas of interest and to order and go through relevant documents. The National Archives’ research guide on Black British social and political history in the Twentieth Century provides a useful starting point.[ref]As a further endnote, Sawh’s (1987: 41) belief that there was a ‘witch hunt’ against him was further confirmed in 1979, when he was wrongly convicted of assault despite being ‘nowhere near the scene of the violence’. Roy was sentenced to three years imprisonment, but released after three months. Speaking of the case, Professor David Dabydeen (quoted in, Sawh, 1987: 93) explains, ‘Upon seeking compensation for the period spent in jail the Appeal Court Judges made the astonishing and unprecedented declaration that, “the three months will be held in credit should Mr. Sawh ever find himself before these courts again.”‘[/ref]

Works cited

- Perry Blankson (2021), The British State’s Secret War on Black Power, Tribune 23 October, accessed December 2021.

- Robin Bunce (2017), Michael X and the British war on black power History Extra 14 October. Available at: https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern/michael-x-and-the-british-war-on-black-power/

- Jenny Bourne, How Should We Evaluate the Race Relations Acts Fifty Years On?, in Khan, Omar (2015) How Far Have We Come? Lessons from the 1965 Race Relations Act Runnymede

- Roy Sawh (1987) Roy Sawh: From Where I Stand London: Hansib

- Rob Waters (2019) Thinking Black: Britain, 1964: 1985 Oakland: University of California Press

- The National Archives (TNA): CRIM 1/4777

- John L. Williams, Michael X: A Life in Black and White London: Century

best article ever

Totally interesting piece further revealing that racism always has been part of the furniture in our so called civilised society.

A monument should be erected in Hyde Park or Nottinghill Gate to honor Mr.Sawh. who have done a lot for blacks in England

We were looking forward every week to listen to Roy as a breath of fresh air to our difficult existence in London. Compared to then racism has dwindled much today, yet it is a scourge will ever linger on here and there within the human society due to lack of human refinement. Thanks to Roy and my blessings!

I would like to receive the pdf from where I stand by Roy swah. Kindly help

Dear Christopher,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.