Michael Rennie was one of the victims of the disaster: he was an escort with 14 children evacuated in a lifeboat (catalogue reference: DO 131/80)

A couple of months ago, I wrote a blog on the torpedoing of passenger ship SS Arandora Star on 2 July 1940. Today, I turn my attention to a similar tragedy – but this time the victims were mainly child evacuees from the UK, looking forward to a safer existence in Canada, away from the danger of bombs, air attacks and invasion at home.

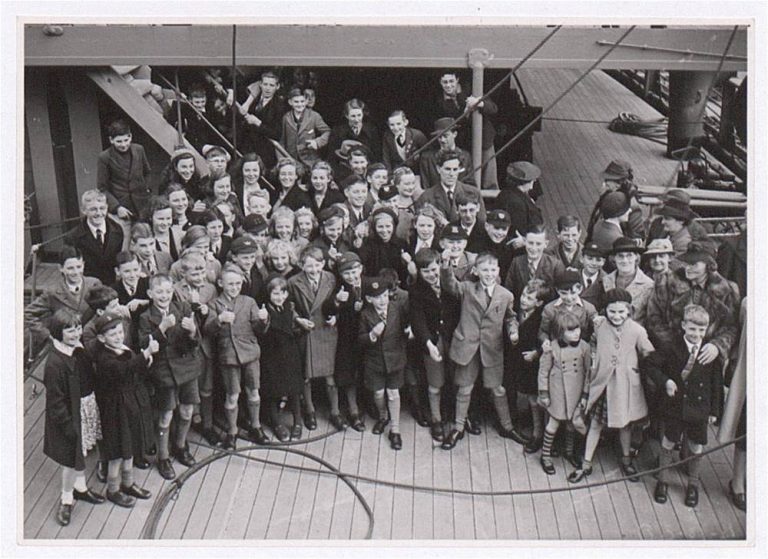

They were just some of the 2,664 children who were evacuated from Britain in 1940 to embark on new lives in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. The scheme which transported them was a government sponsored scheme known as the CORB Scheme (Children of the Overseas Reception Board). It was not set up until June 1940, a few years after private schemes had evacuated some 14,000 children from Britain to new lives overseas as war neared.

Evacuating children overseas

It was a unique period in British history. In May 1940 the threat to the UK from German air attacks grew and the possibility of invasion heightened, leading to spontaneous offers of hospitality and refuge for British children from overseas governments. These began with Canada on 31 May, where the government forwarded offers from private households to the UK government. In a few days similar offers were received from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the United States. To coordinate the British response to these offers, CORB was established. Its terms of reference were: ‘To consider offers from overseas to house and care for children, whether accompanied, from the European war zone, residing in Great Britain, including children orphaned by the war and to make recommendations thereon’.

CORB and its advisory council dealt with applications for settlement; sorting, selecting and approving the children; contacting the parents; arranging parties at the ports; and seeing them off. It also corresponded with the Dominions authorities about reception and care overseas and the eventual return of the children after the war.

Carrying of CORB children to New Zealand by boat – reports by Ships’ Captains, 1940-1 (catalogue reference: DO 131/15)

Unlike those children sent abroad by institutions such as orphanages, for CORB children theirs was a temporary exile, at least in theory; they had homes and families to return to after the war.

From the very start of the operation between June and August 1940, the popularity of CORB was assured. Parents were prepared to endure indefinite separation to know that their children were living in safety, and the Board was inundated with over 200,000 applications before deciding to suspend further entries in early July. Most of the chosen children lived in areas deemed more vulnerable to air attack; some also came from families already split up by evacuation within Britain. The authorities agreed to provide a proportion of accommodation for Scottish applicants, and each sailing party was selected with care to represent a cross-section of society.

In total, CORB despatched 2,664 children, who became known as ‘Seaevacuees’, over a period of three months on 16 ships. Canada received the bulk of them – 1,532 in nine parties. Three parties sailed for Australia, with a total of 577 children, while 353 went to South Africa in two parties and 202 to New Zealand, again in two parties. A further 24,000 children had been approved for sailing in that time and over 1,000 escorts, including doctors and nurses, enrolled. At its height, CORB employed some 620 staff.

The sinking of the City of Benares

Many more would have travelled overseas had it not been for the disastrous events of 17 September 1940, when the SS City of Benares – packed with 197 passengers, including 90 children – was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic. The ship, sailing from Liverpool to Canada, was struck down at 22:00, when it was 600 miles from land. Many later claimed such an event was bound to happen, and that shipping children overseas had been an extremely perilous course.

- DO 131/80 Escorts Files. Rennie, Michael. Michael Rennie’s application to join CORB as an escort

- DO 131/80 Escorts Files. Rennie, Michael. 12-year old Louis Walden’s moving witness account of the tragic events and heroic bravery of Michael Rennie

The consequences of the attack were devastating, even by wartime standards, and it marked the effective end of all overseas evacuation from Britain, both public and private. 70 CORB children were among 134 passengers killed, along with 131 of the 200-strong crew; loss of life was exacerbated by severe weather in the night, including gale-force winds, storms, rain and hail. The ship, built in 1936 and weighing 11,000 tons, had been fitted with up-to-date facilities for carrying passengers, with special provision for children. One of the last CORB vessels to sail, it had passed safety checks from Ministry of Shipping representatives prior to sailing. It left Liverpool in convoy on 13 September, with lifeboat accommodation for 494 people and additional buoyancy apparatus for another 452; regular boat drills were held on the voyage. Yet the combination of weather, darkness and isolation was to result in a death toll that shook Britain and its allies, and became one of the war’s most notorious events.

Although evacuation ceased when the SS City of Benares was torpedoed in September 1940, CORB remained active. It was only disbanded, along with the advisory councils, four years later, at which point the perceived German military threat had diminished.

Insight into the lives of CORB evacuees

But what happened to the children evacuated before the City of Benares tragedy? The series of records DO 131 provide a fascinating insight into the lives of these children, including their names, dates of birth, their parents’ details, information about where they were placed on arrival overseas and how they fared in health, and at school and in employment. The cards also reveal if they returned to the UK after the war ended or whether they decided to stay in their adopted country. Some withdrew from the scheme and eight unfortunately died while in placement.

The cards reveal both happy and sad stories. Some children settled well with the placements, while others didn’t. John Parry had five different placements in Canada between September 1940 and January 1943 and withdrew from the Scheme, returning to the UK in August 1944. Meanwhile, 14 year old John Doughty was placed with his grandmother in Hobart, Tasmania and settled extremely well, taking a junior post at the Mercury newspaper in 1942 and joined the Australian Imperial Forces in 1944, eventually settling in Australia with his parents joining him soon after the war ended.

In the Health reports, children’s illnesses ranged from standard submissions such as rheumatism, laryngitis, shingles, mumps, whooping cough, and diphtheria to the more unusual such as ‘cricket ball has injured tooth’, ‘broken leg’ and ‘fell off bicycle and broke wrist’.

Under the terms of CORB, children were due to return only ‘as soon as practicable’ after the end of the war, and many were away for four or five years. In that time they forged new family ties and were shaped by a country outside their parents’ experience. Ronald Daw, for example, remained permanently: his mother had died in February 1941 when he was seven, and his placement guardians Mr and Mrs Mayhill applied for guardianship. Violet Oades stayed for other reasons. She was one of the oldest CORB children, evacuating to New Zealand at the age of 15 in 1940. By the time the war had ended she was engaged to be married, and did so in 1946.

Hi,

I am so pleased to see this article! I am just defending my PhD on British evacuees in Canada (at the University of Western Ontario). I have referenced DO 131 extensively and have used the “case files” mentioned to build a complete evacuee database (which also includes private evacuees who came to Canada).

I hope I can return to Kew again soon for my next project!

Best wishes,

Claire

Is it possible that there was a Roman Catholic priest on board the City of Benares called Father Rory O’Sullivan? If not he was on an evacuee ship and I am trying to research this. He was in fact rescued and survived.

Can you help

Hi Patsy

I couldn’t find Father Rory O’Sullivan on the passenger list for the City of Benares but you can search for passengers on board other vessels by name of passenger at http://search.findmypast.co.uk/search-world-records/passenger-lists-leaving-uk-1890-1960

Yes, Rory O’Sullivan was on the ship. He was on Lifeboat 12 and survived. He wrote a memoir. Are you a relative by any chance?

Did anyone ever vet the passenger list prior to embarkation to name the children who were scheduled to sail on the City of Benares, but got “bumped” at the last minute?

Did someone “pull rank” to get children aboard the ill-fated ship?

my mother told us that she and her sister were due to sail on this boat, but her mother stopped them from going at the last moment. Their names were Joy and Jessie Quinion, from Heston, Middx. I’d love to know if this could be verified.

I live in Little Abington in Cambridgeshire. The first occupants of our house, built in the 1950s, were Roy (Jock) Fraser and his wife Vera. Jock and his wife moved out of the village many years before we moved in, so we never met them.

We heard from neighbours about the loss of Jock and Vera’s two children on the City of Benares, and for some time I have been trying to find out some information about the children.

I have looked at information online about those who were lost in the sinking but could not find any children with the surname Fraser. I have located Jock and Vera’s marriage in1933 in Wandsworth Registration District, but can find no subsequent birth registration details of any children.

Vera’s name before her marriage to Jock was Vera T Browne, and I don’t know whether the two children may have been from an earlier marriage (if there was one).

One of the reasons why this tragedy was talked about locally was that a neighbour opposite, Christopher Tulitt also sailed on Ellerman lIne ships as a young man during the Second World War. He was torpedoed and rescued three times. Chris went on to become an architect, and was later the Chairman of South Cambridgeshire District Council.

I would be very grateful if you could find some information about the two boys.

Thank you.

Hi Tony,

I’m afraid we’re unable to help with research requests on the blog. If you go to our ‘contact us’ page – https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact-us/ – you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by phone, email or live chat.

Best regards,

Liz.

The wife of my fathers 1st cousin (Emma Pine) and daughter (Diana) age 6 were aboard this ill-fated ship, the City of Benares, sailing to Canada. I have been informed that the ships escort had been removed as a ship with a consignment of goods, approaching Britain was considered to have greater priority for need of the escort. If this is true what a disgrace!

Both Emma Pine age 34 and daughter Diana are listed on the CWGC webpage.

April Wood Ashton

My father was on board with his wife, she died of exposure in the life boat ,

He was forever angered at the Royal Navy ,who he held fully responsible for the tragedy . R.T Deane was on his way to take up his navy post in the Bermuda .

My two brothers Kenneth and Geoffrey and I were due to be evacuated on the City of Benares by luck my brother Geoffrey took ill a day or so beforehand so my Mother decided that all of us would not go. I believe some other children in our street also did’nt go for this reason how very fortunate for us. We have all gone on to celebrate our Golden Wedding Anniversaries.

My Dads sister Betty Unwin aged 12 was on the City of Benares. She sadly was not one of the survivors. Her Dad was a shop keeper near the Liverpool docks and thought it would be safer for her to be away from the war. I am told my Nan never got over the loss of Betty. Full of guilt for not fighting enough to keep her at home. I think I’ve read from survivors stories that Betty got into a life boat, but must have died of exposure in the life boat. These details are not confirmed, only that she never made it back home.

Hi My father was on an escort destroyer HMS Active H14. They were inbound to Liverpool with another convoy. I remember him telling me that they passed the City of Benares on her outbound journey. I told me that he remembered seeing the children on her deck and they all waved at the passing ships.

My father was an anti submarine (ASDIC) operator. Some hours later they heard the news that the City had been torpedoed. They immediately turned around but took some time to get to the scene. It was dark and he remembered seeing the lifeboats with dead children in them and many bodies of children and adults in the water. His captain, Mr Turner, gave instructions to sweep the area with ASDIC for as long as possible whilst they assisted with the rescue. My father said that although he picked up traces of an echo because of the darkness and the possibilities of survivors in the water it was not possible to drop depth charges. This experience upset my father badly and he always said it was his worst experience as he had my brother and mum back home and thought of the terrible loss to families.

I live in NYC and am just learning about this horrible tragedy now from reading The Splendid and the Vile. Does anyone know anything about the U boat that committed the act? Who the U boat commander was and whether he survived the war? Thank you. Peter Aronson peterEaronson@gmail.com

My mother told me that she and three of her siblings were booked on the ship to go to relatives in Canada. But at the last minute their mother had second thoughts and she cancelled their tickets. I would love to know if their names appear on any lists.

The ship was torpedoed by the German submarine U-48 commanded by Hans Rudolf Rösing. Hans-Rudolf Rösing (28 September 1905 – 16 December 2004) was a German U-boat commander in World War II and later served in the Bundesmarine of the Federal Republic of Germany. He was a recipient of the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, awarded by Nazi Germany to recognize extreme battlefield bravery or successful military leadership.

Just thinking today. I was one of 117 children evacuated to New Zealand, with my sister, on RMS Rangitata. We left Liverpool 30 Aug 1940 (Dunkirk still fresh in memories – Battle of Britain at its height – U-boats having the time of their lives in the Atlantic!). The convoy was attacked two nights out. Five ships were sunk and two damaged. One of those was SS Volendam, carrying evacuees to Canada. All were saved but some set off again a while later – on the City of Benares. We spent 5 years in that wonderful country although my sister and I had to be separated. Was wondering just how many of us are left today.

My niece pointed the slinking of the city of Benarus tragedy to me this morning. My brother and I were to sail on the next ship out to Canada and my mother was busy making us pyjamas and such to take with us. Our trunk was at the front door being filled when suddenly everything was emptied from the trunk and put in our bedroom drawers. Mr Churchill had said we could no longer go. We lived in Waterloo Liverpool and were very used to the sea. My brother was 11 and I was 6. I think parents of the day deserve to be honoured.

My Cousin Colenzo (known as Colin) Rodda lost his life in this tragedy, he was 6 years old and lived in Hillingdon Middlesex. I never new him as I was born in 1946.

The family never received any information of his death other than he was lost at sea.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinrich_Bleichrodt was the commander of the U-Boat.

Rev William Henry King an Anglican minister was accompanying the children on their voyage to Canada on the City of Benares . He was lost at sea .He was the only son of Alice and Henry King of Hamilton Ontario. William’s father (Henry ) was my mother’s cousin.

My late father (Alex Anderson) from near Perth, Scotland was Radio Officer on the SS Peder Bogen and sailed alongside the City of Benares in the same convoy from Liverpool. He recalls in his (1939-45) memoirs seeing children playing on the deck on the journey before tragedy struck. He gives a harrowing account of a ‘signal flare rocket’ being fired that meant that all ships (being with our naval escort) were now ‘on their own’ and would separate as part of the recognised escape protocol. He relates how badly the crew were affected by this tragedy, however was was personally pleased to hear later that a young girl (Joyce Keay) from his own village who was a passenger, survived and successfully reached Canada. He was always grateful to survive the North Atlantic convoys given that four of the six vessels he served on were lost to enemy action.

… should read ” … (being without naval escort) “

It was very moving to read the postings here. I learned of this tragedy only tonight, February 14, 2022. I wonder that someone wants to know the name of the U-Boat and the name of the commanding officer of that U-Boat. It reminds me of the focus of the main authors of the Treaty of Versailles – to focus blame rather than fully consider the ramifications of the terms of the Treaty, which the world is still dealing with today.

My late mother, Joan Millient Edith Benge, was born in London on the 18th of March, 1925. She was about 15 and was going to go to Canada on the SS City of Benares to be safe from the bombing. Her father had been in World War One, and was fraught with the war. On the night before she was to go, he had some sort of nightmare to do with her, and the next day he was adamant: he forbade her going to the ship. When in later years my mother and I were watching a documentary on the sinking of the City of Benares, she told me that she was to go on it, but that her father told her she was no going…

She could very well have been one of those who died…

Might there be a crew list available for this ship, and particularly with respect to this voyage?

My mum, and younger brother and sister were set to be on this ship… their father, my grandfather , changed his mind last minute saying he would rather keep family together … needless to say I wouldn’t be here, and neither would 6 of my 19 cousins.. they lived In corringham where the oil refinery was…

I am currently (March 2023) publishing my late father (Alex. Anderson) WWII memoir ‘Hunter to Hunted – Surviving Hitler’s Wolf Packs’ (Diaries of a Merchant Navy Radio Officer, 1939-45) (https://www.huntertohunted.co.uk) in which he records the S.S. City of Benares tragedy. Sailing alongside the vessel in the same convoy, he watched the children playing on deck before the tragedy unfolded. An interesting post script to the event was on his next home leave to the Perthshire village of Methven, near Perth, Scotland. It transpired that, unbeknownst to him, one of the children on the vessel was a native of the same village and from a family he was familiar with. The happy ending was that she survived and was at the time of his writing (1998) still living in Canada.

Claire Halstead, is there any evidence that the Nazi’s might have targeted this ship because Rudolf Olden, who had written a damning book on Adolf Hitler and was part of a resistance movement, was on board? The Nazis had just revoked his German citizenship. I just recently became aware of Rudolf Olden while doing research on his half-brother, Peter Olden, who my father often referred to as his “oldest and dearest friend.” He met Peter when he was an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, and Peter was in some kind of what appears to have been a post-doctoral program. Peter had received is Ph.D. at the University of Tübingen. He became a naturalized U.S. Citizen in 1933 in Louisville, Ky,. when he was teaching at U of L The statement afterwards that they thought it was a troop ship could have been a cover story. He joined the U.S. Army during WWII to fight the Nazis and rid his homeland of that scourge. There is something about this sinking that makes me suspicious. Are you aware of any evidence that would make my suspicions warranted? — Carl

I note that 7 of those contributing comments to this blog are either individuals who narrowly escaped boarding the City of Benares before she embarked on her last voyage or descended from them (David Weston, christine walker, Alexander Black, Alison, Shirley Morton Cooper, Stephen Ryan, Susan Sylvester). That “escape” doesn’t detract in anyway from the horror experienced by victims or survivors and in the case of my mother (who escaped) forged a deep friendship with a survivor that lasted decades. I will be visiting the archive to see if there is any record of your family names in DO 131/20 and other locations (Greenwich Maritime Museum, Liverpool Maritime museum, IWM) – it is a struggle because obviously, they are not on any passenger lists. Please let me know if you have already tried this and failed to find anything.

It’s incredible that I’ve just stumbled across this archive. I’ve just been listening to my Grandmothers stories regarding the war, and she was incredibly lucky not to have been on this ship. She said her most heartbreaking memory was being evacuated to Shropshire (from Liverpool) and being taken in by a couple that owned a green grocers. My Grandmother shared a room with Betty Unwin, and Betty was offered the opportunity to go and stay with her Aunty in Canada, who was a doctor (or something along the lines). Betty said to my Grandmother that she was more than welcome to go to Canada with her as her aunty was happy to take in my grandmother too, however my Grandmothers father refused. If it was not for my Grandmothers father refusing at the time, my Grandmother would have likely been on the ship and not have made it, like Betty, and I would not be here to ever write this message. I sincerely hope this message gets back to Julie, as my Grandmother says she was a lovely girl and was very fond of her.

I was/am thinking about applying for a position with the John Ellerman Foundation. Reading around the history of the Ellermans, a sentence about the tragedy of the City of Benares was mentioned. I was shocked at the huge loss of life, especially the children and this led me to started researching this tragedy. Having now read extensively about that fateful day, and being a mother myself, I wonder what I would have done…knowing me, I don’t think I could have bear to be parted from my son. My heart goes out to everyone affected by this tragedy, what the victims experienced on the night is beyond comprehension. The memories of people who have commented here are interesting, poignant and sobering.

My mother Gwenneth Dunkley and her sister Beryl were booked to be passengers with a chaperone, Brenda Seaton. They were unable to go at the last minute as my mother contracted measles, and was obviously at risk of infecting others on board. And so their lives were saved.

To Shirley Morton Cooper.

We were due to go on the next sailing to Canada too, we all still have our passport photos, I think I was about 6-9 months old, I only know what my mum told us and that was because of what had happened to the previous boats we didn’t go.

I didn’t take the chance of asking her anything else, she died suddenly at 59.

This topic was brought to my attention due to a book I read. (Torpedoed The true story of the world war 2 sinking of “the children’s ship” I highly recommend it was a great book and was very closely based on the events that happened.

Hello, I am writing from the other side of the conflict. My grandfather was an engineer on U48 under Captain Lieutenant Bleichrodt when they attacked the City of Benares. He only told me about this incident when I was an adult (as well as many other things, 3 trips on U48, with the speedboat in the Baltic, as a reinforcement on the Eastern Front and capture in Odessa, then Russian camp in the Urals) it haunted him until his old age that he or the crew were to blame for the deaths of so many children. He sat there and cried like a little child. He said that nobody, not even Bleichrodt, knew about the children. Unfortunately, he is no longer alive.

Both sides in this conflict could learn so much or would have had so much to learn. Whether the Germans or the Allies. But we are still not doing any better today. Man is a beast.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.