One of the great challenges for all kinds of history researchers is the way in which relevant archives, for the historical narratives we all want to tell, can be distributed across different sets of records within individual archives and indeed across many different archives. Although tracking and linking subjects and individuals from record series to record series and across various archives might be initially difficult or confusing, it can (once a researcher starts down this road) be regarded as an enjoyable exercise in its own right and definitely a process that provides a more rounded and nuanced account of the subject of our enquiries.

For the last few years I have been engaged (with many others) in a collaborative project to find, analyse and make sense of a host of records that provide the voice of the Victorian poor across England and Wales (see footnote 1). These would include letters and petitions from paupers, the wider poor and their advocates. Such materials might exist in their own right (as individual letters and petitions) but they might be published in newspapers. Additionally, these same groups of people might provide witness testimony to poor law investigations when complaints were made or ‘scandals’ erupted. Yet narratives are enhanced when the archival net is spread its widest.

For example, I came across a case sent from the Berwick-upon-Tweed Poor Law Union (PLU) in Northumberland to the Poor Law Board (PLB) in London in the central poor law records held at The National Archives (footnote 2). This was a letter from the clerks of the Berwick PLU concerning Joseph Manderson and included a bundle of other (copy) letters and witness statements concerning Joseph’s experiences. In one of these enclosures Alexander Laidlaw, the Berwick workhouse master, claimed that Joseph had been treated with ‘unusual harshness and severity which requires your investigation’. Joseph himself stated how he sought work at the Detchant Moor Colliery in October 1855. He was told they could not employ him but, it being late, he might stay overnight in a cabin the colliery owned. Being thirsty, he cast about in the cabin for something to drink and uncorked a bottle he found. The bottle contained gunpowder and the unfortunate Joseph then found himself at the centre of an explosion as the powder exploded and,

I was struck on the forehead and knocked down. On getting up I found my Clothes on fire in several places and both hands severely burnt as also my face and neck

Injured, he stayed in the cabin all night and in the morning was given florence oil by some of the pitmen to dress his wounds. Because of his injuries he was unable to leave the cabin for four days. When he did, he walked to nearby Detchant and from there he made his way to Belford. On reaching Belford, he was ‘wet through to the skin’. He went to George Scott’s house (the local relieving officer), explained his situation, and that he wanted to stay at the workhouse for medication assistance. In his absence, Scott’s wife said that Joseph could stay at the workhouse but only for one night. At the workhouse he was told there were no beds available and he was locked in a room with no beds ‘and only sloping boards for sleeping on’. Later in the evening Scott, the relieving officer asked Joseph

‘Who sent you here and what right have you to come here’. He jumped round me like a man either drunk or mad and said ‘You have no right here and you must go out. I tried to speak, but he would not listen – ’ He said you have imposed upon my wife and if I had been at home you should not have got in here for I would not have let you’. He told me several times to go about my business – I said will you have no mercy upon a poor old man in the situation I was in and with my hands in such a state.’ He said again that I was to go about my business – I asked him for mercy’s sake to allow me to stay a few days and get medical assistance

Scott, finding that Joseph had 4d on his person, said if he knew he had money he would not have been allowed in the workhouse. Joseph asked Scott ‘if I was to be allowed to die in a Christian Land without medical aid – He said that he did not care whether I died or lived but that I should not remain any longer there that night’. A medical officer looked at his injuries but only to his left hand ignoring his right hand and face. In the morning he was told ‘You must go away it is fair weather now you are not to get stopped here’. The morning was stormy and wet and Joseph ‘left with tears in my eyes’ walking some 20 miles over three days to Berwick via Lowick and Scremerston where he was ‘ordered into the (Berwick) Workhouse where I have been ever since I am 78 years of age and am a native of Scotland – and I make this solemn declaration etc etc (footnote 3).

We now turn to the locally held archives of the union itself, which are held at the Berwick Archives where the case appears in the recorded meetings of the Berwick guardians. Here, Laidlaw, the Berwick workhouse master, reiterated much of Joseph’s account. However, and here is the beauty of record linkage, he also added that the Belford PLU has been legally negligent in their duties as they should have provided full medical care and relief for Joseph. In refusing to do so, he alleged that Belford were pursuing a policy of forcing their responsibilities onto other poor law unions in the area; in this case the Berwick PLU. Thus we are invited to see the treatment of Joseph not as a mistake nor a one-off instance of ill-treatment, but as the result of deliberate local policy (footnote 4).

A second example of how record linkage provides a more nuanced view of the past concerns Mary Herbert, a pauper living in York in the 1840s and 1850s. We begin with sampled references to Herbert in the local York PLU archives where we find multiple references to her in the outdoor relief lists. We find her in different years allowed different amounts of outdoor relief in 1841, 1845, 1846, 1847 and 1848 (footnote 5). Each of these local records point to a narrative of constants; a long-term pauper, on long-term relief, a long-term York resident. However, the central poor law archives find different.

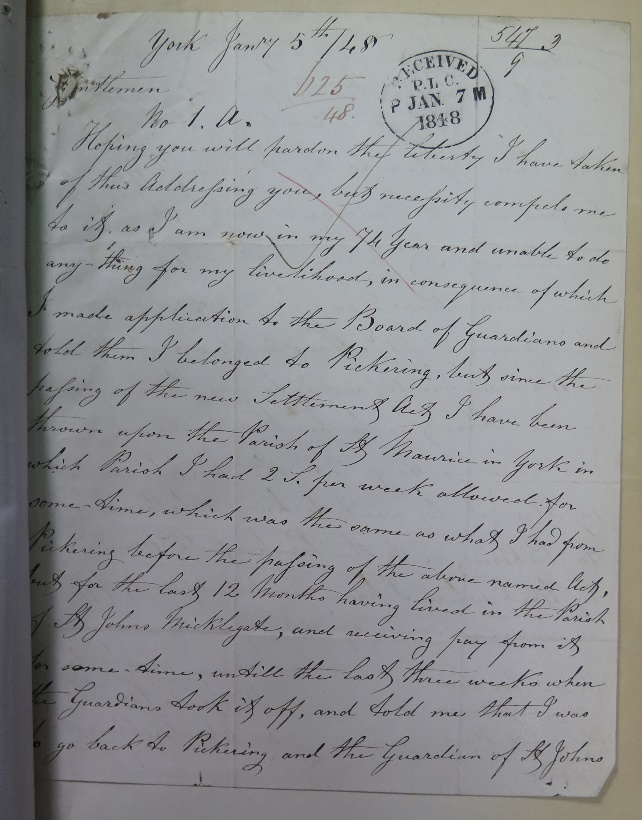

In early 1848 Mary wrote to the PLB informing them that the York guardians had at some point stopped her relief and when she made a re-application they determined that she actually belonged to the Pickering PLU some 26 miles away quoting the ‘new Settlement Act’ (footnote 6). She was ordered to go back there and one of the guardians had threatened ‘to throw my things into the Street’. Mary, in clear distress asked the Central Authorities if the York guardians had the law on their side ‘and if he can throw my things in the Streets as he has threatened, and if they can force me to go into the Workhouse at my Age.’ (footnote 7) The reply from the PLB to Mary stated that they could not intervene but they would send a copy of her letter to the York PLU for their observations (footnote 8). The guardians responded that Herbert’s relief had been stopped because, when asked to give evidence regarding her settlement, she had refused (footnote 9).

The reply to the guardians must have been most unexpected. The PLB stated that discontinuing Mary’s relief on such grounds was unjustifiable. Moreover that in so querying her settlement ‘the Gns would appear to have used means to extract evidence in a matter where they had no jurisdiction’. ‘Surely’, the PLB explained, ‘it is not to be expected that paupers will in all cases be ready to give evidence as to their settlement voluntarily’. They reminded the guardians that they must by law relieve those who were destitute (footnote 10).

We see then how the two sets of records complement each other: one picture provides a narrative largely built around notions of continuity and constants. A second, from the central records, reminds us that the payment of relief is an outcome and one that comes at the end of a process of negotiation and contestation.

Both Joseph Manderson and Mary Herbert’s cases demonstrate the value and indeed the necessity of record linkage across individual archives as well as across sets of records with individual archives. The examples here relate broadly to cases of Victorian welfare under the New Poor Law, with examples of how the local poor law and national poor law collections provide complementary rather than identical information. However, the principle is fairly widely applicable across subject matters and give us, as researchers and readers in history, the opportunity to engage with well-developed and balanced narratives.

Footnotes

- This work was undertaken with research with Nottingham Trent University and the Pauper Letters Research Group (of volunteers). See also About the Project – In Their Own Write.

- The central poor law authority in London from 1834 to 1847 was styled the Poor Law Commission (PLC); between 1848 and August 1871, the Poor Law Board (PLB); and from 1871 to 1919, the Poor Law Department within the Local Government Board (LGB). The correspondence of the Centre is held in record series MH 12: Poor Law Union Correspondence, 1834-c.1900.

- The National Archive (TNA): MH12/8983, 46155/1855, W and E Willoby, Clerks to the Berwick PLB, to the PLB, 1 November 1855.

- Berwick Archives (BA): GBR 43/333, Berwick upon Tweed, Guardians Minute Book, June 1854-March 1856.

- Explore York (Archives): EY(A): PLU/3/1/1/22, York Union Application and Report Book, City District, December 1845 and March 1846, 76; EY(A): PLU/3/1/1/24, York Union Application and Report Book, City District, March and June 1847; EY(A): PLU/3/1/1/28, York Union Application and Report Book, City District, September 1848, 133.

- She almost certainly refers to an Act to Amend the Laws Relating to the Removal of the Poor, 9 & 10 Vict. c. 66, 1847; and An Act to Amend the Procedure in Respect of Orders for the Removal of the Poor, 11 & 12 Vict. c. 31, 1847.

- TNA: MH12/14400, 625/1848, Mary Herbert, York, to the Poor Law Commission, 5 January 1848.

- TNA: MH12/14400, 625/1848, PLB, to Mary Herbert, York, 10 January 1848; and 625/1848, PLB, to Henry Brearey, Clerk, York Union, 10 January 1848. Mary was writing in the transition from the PLC to the PLB.

- TNA: MH12/14400, 1913/1848, Henry Brearey, Clerk, York PLU, to the PLB, 17 January 1848.

- TNA: MH12/14400, 1913/1848, PLB to Henry Brearey, Clerk, York PLU, 27 January 1848.

I agree on record-likeage across archives but it does depend on the archives having catalogues that name individuals, alas TNA do not do that as in the case of William Rutherford Benn (father of renowned actress Dame Margaret Rutherford who was famous for playing ‘Miss Marple’). As far as I know there are only one person apart from myself who knows where the file on Benn is and that was by sheer luck. It is not the only such example. You can for example look at the women in Broadmoor at the time of the 1921 Census and they can be traced through Lunacy Registers at TNA/ancestry and other records at TNA as well as the Broadmoor case files at the Berkshire Record Office.

Hello David, thank you very much for commenting on the blog and the really interesting note on the Dame Margaret Rutherford point. I think you are right that the better catalogued the archival collections are (and we are continually cataloguing our collections) the easier it is to establish those record linkages. But I would want to challenge you somewhat on it depending on the archives having catalogues at name level. I think this is what we mean by the great challenge that record linkage presents to all history researchers. In reference to the poor law archive, that I blogged about on here, it is somewhat split between the central poor law authority’s archives (held at TNA) and the union archive (held at multiple county/borough or other local archives). This does mean we can browse locally the surviving local poor law guardians minute books, letter books, application books, punishment books etc. as well as the specific union correspondence (and other series) held here. Finding names or subject areas in the one prompts us to examine the other and (in the case of this particular set of archives) pooling the information found in local and national poor law collections give us a more complementary and rounded picture to help build our understanding of how the poor lived.

Some excellent points are made here. It’s tempting to see the pauper correspondence as a self-contained corpus of letters, between the poor or their advocates at local level and central government in London. But the Joseph Manderson case shows that where there is linkage with other sources, it can add a whole new dimension. It may help us better understand the local conditions that are driving local decisions, which in turn may persuade us to re-interpret individual cases. It’s an ongoing learning process!

Being able to make linkages is a very useful tool and no doubt will further develop as time goes on. It enables us to further understand the lives of people and how earlier or wider spread events shaped their lives and future generations.

As a student this is a great reminder that researching multiple sources can give a fuller picture to a narrative. Record linkage can also be a useful way to check those pesky mistakes that can work their way into research when only one primary source is used.

Paul, your blog provides an excellent example of the importance of using multiple record types in an attempt to unravel what happened in the past. One side of the story is rarely enough. Exploring the contextual environment of any single event or life story through the use of records from diverse sources enriches our understanding of the past, especially when those stories involve people or events that history tends to overlook, as in the case of the Pauper Letters project at TNA. Bringing these fragments of individual stories together not only helps to illuminate individual lives but also helps us gain a more complex understanding of the communities they come from and their place in wider society. Which, to David’s point, can be facilitated further by enhanced cataloguing.

That’s the essence of it – complementary not identical information and so often the juxtaposition throws up far more than nuance. The recent report on Rotherham and the content and context of other sources will find future historians needing access to so much more than the official government and police reports.

A really interesting article in its own right, Paul, but also one which highlights the real importance of linkage between the wide range – both in terms of record type and geographical location – of sources needed in gaining a more accurate and balanced understanding of historical events.

Certainly, linking up sets of records should be made as easy as possible, thus helping to round out the study of the life of ordinary people in Victorian England

Really interesting to see the worked examples of how things are not always as they seem when only one source is used. Newspaper reports, some of which appear in the MH12 records when they’ve been sent in by a correspondent, can also be useful in providing context or relating ‘what happened next’.

This is an interesting article Paul, thank you. My (long ago) days as a student of history has drilled into me to try to be aware of bias in historical documents. Being able to view more than one primary historical source, via record linkage, provides a fuller picture of the person, events and/or period of history that is being researched and that has to be good for everyone. Access to such documents is a key element here I feel.