Whenever I think of spies my first thought is always of a James Bond-type character, dressed in a suit loaded with gadgets. Or of someone hiding round corners, bugging rooms and watching you through a newspaper with cut-out eye holes.

Of course I know that the reality isn’t that glamorous (or comical), but something I rarely consider is that my perception of spies, if I really think about it, is actually based on something very real. There are spies among us today, operating at this very moment, who are doing incredibly important work.

These spies aren’t a modern phenomenon – we have had spies for centuries. The history of espionage is embedded within our popular culture but often the truth about real spies is buried. However, with the help of archives and records it is possible to uncover the real stories behind what we think we know.

One spy story that is rarely talked about is that of Noor Khan, who you can find out more about in this blog. I spoke to Hannah Carter, an Education Officer here at The National Archives, to find out more about Noor and why we rarely hear about women like her.

Photograph of Noor Khan taken from her personnel file HS 9/836/5

[Katie]: Noor Khan’s job title wasn’t ‘spy’ was it? She was a wireless operator, so how did she become involved in espionage?

[Hannah]: Noor had actually enjoyed a successful career as a children’s author before war broke out in 1939. From that point onwards her life changed dramatically, and her family moved from France to London. Initially she joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and then secretly interviewed for the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1942.

The SOE’s mission was sabotage and encouraging revolt behind enemy lines. Noor’s cover was that she was enlisted in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, as this was the only combat role open to women in the Second World War. She had many of the skills that the SOE were looking for – she spoke French without a trace of an accent and was already an adept wireless operator. In fact she had been under Secret Services observation throughout the war. In order to work as a wireless operator Noor had to develop her coding and decoding skills, and she also had to increase her Morse code speeds.

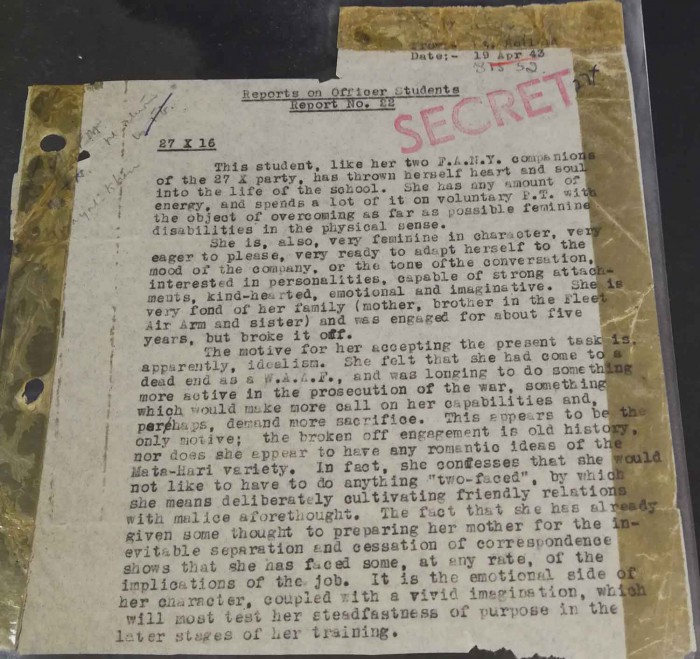

Report on Noor Khan’s character and motivations dated 19 April 1943. Taken from her personnel file HS 9/836/5

[Katie]: How do you think the role of wireless operator compares to the role of an archetypal spy?

[Hannah]: It didn’t involve as many James Bond-style gadgets, probably! Although the wireless transmitter itself was incredibly difficult to operate.

Noor was working in an extremely dangerous environment. The average life expectancy for wireless operators in occupied France was just six weeks. The Germans had developed methods to detect where transmissions were being sent from, so Noor had to constantly transmit from different locations, like rural farmhouses.

I suppose the idea of a spy being detached and isolated applied to some extent. Noor was left as the only transmitter in Paris. Also she wasn’t able to divulge her whereabouts or role to her family or loved ones. They only found out what really happened to her years after the war had finished.

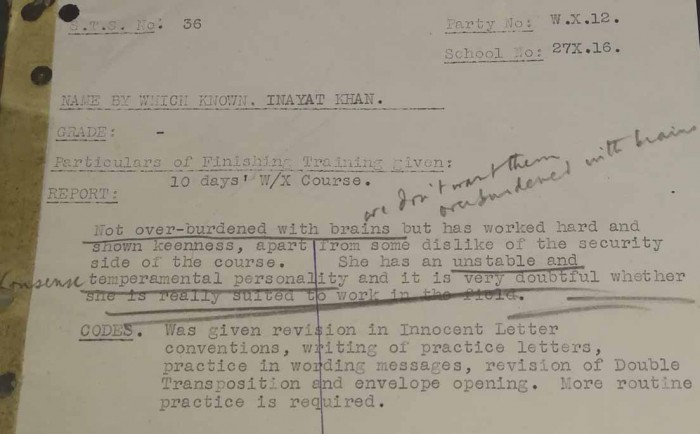

Report on Noor Khan’s Training dated 21 May 1943. Taken from her personnel file HS 9/836/5

[Katie]: Noor wouldn’t have been the only woman to have worked undercover during the Second World War. Why do you think it is that stories like hers don’t come to mind when thinking of wartime espionage?

[Hannah]: I think it is interesting that we don’t associate the qualities of spies with women as readily. This was evident in the negative reaction of many in 2016 to the idea that Gillian Anderson, a woman, could play the role of 007.

In popular culture spies are usually depicted as overtly masculine, while women are decorative. As Noor’s story demonstrates, women’s abilities were often questioned at the time. Indeed although championed by Maurice Buckmaster (the head of the French section of the SOE), there are negative remarks to be found from officers in her files. In reality, she demonstrated many of the skills needed to operate in such a dangerous field.

There are other extraordinary stories of women to be found, such as Krystyna Skarbek, who saved two SOE agents from execution and threatened the German officer responsible that, if they died, he’d soon join them! Hopefully in the future we will see a more nuanced picture of what a ‘spy’ looks like.

On the Record: a new podcast series

On the Record is a new podcast from The National Archives. In our first three-part mini-series we focus on espionage. With the help of historians and records experts here at Kew, we are going to use personnel files, secret government reports, and declassified correspondence to uncover the true stories of famous spies.

In episode one – ‘Archetype of a Spy’ – you can hear more from Hannah about Noor Khan. You can also find out about the history of espionage, from the Anglo-Saxons to the present day, all with a bit of James Bond and the spies we are more familiar with thrown in.

The podcast is available now on the Archives Media Player. We will be releasing further episodes of the podcast regularly, so make sure to subscribe to the series to keep up-to-date.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

In this interesting post the author relates how she contacted a colleague about Noor Inayat Knan and asked ‘… why we rarely hear about women like her. …’

I beg to differ.

It’s very difficult NOT to read, see or hear a vast amount of information about Noor Knan and other brave women like her in SOE F Section.

One can’t look at the appropriate section at the National Archives own bookshop, most public libraries, go to a war-related museum or – in many cases -simply walk down streets. In all these places books, artefacts, statues and blue plaques all honour what she and her fellow women agents did in Occupied Europe.

And that’s leaving aside the many press articles together with film and tv documentaries and drama productions.

What we rarely hear about are people like Frederick Amps who was trained as an SOE operative and sent to France as second in command to Francis Suttill, (PROSPER) head of the Ill-fated PHYSICIAN network in the Paris area.

It appears that while Amps was good at many of the more practical tasks associated with the network he was not able to master the skills needed as Suttill’s deputy.

Having been born at Rueil-Malmaison not far from Paris, he was quietly let go from SOE and lived with his wife in or near Paris until he was arrested and subsequently executed.

His place as PROSPERS deputy was filled by Andrée Borrel, yet another courageous woman – and one who was executed with other SOE F female colleagues at the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp.

Sorry to add to my previous lengthy post on this subject but although SOE personnel were treated by the enemy as spies (and are often seen by the general public as such) they were not. Their role was to aid resistance groups (in whatever country they were operating in) in harassing German, Italian and later Japanese occupying forces. On short in Churchill’s famous phrase ‘set Europe ablaze’. This put them – and particularly the women agents who unlike the men were not covered by the Geneva convention as a formal enemy combatant – in a unique and highly dangerous situation.