Many people will have been amazed at the depth of feeling generated on both sides of the recent court battle over the re-burial of the body of King Richard III. Before the archaeological dig began, the University of Leicester, which led the excavation of Greyfriars Church in 2012, was granted a licence by the Ministry of Justice which stated that if the remains of Richard III were found they were to be re-interred in Leicester Cathedral or another legal burial ground. However, in a case that has now been dismissed, the Plantagenet Alliance, a group of Richard’s distant relatives, challenged this decision; arguing that it was Richard’s desire to be buried in York.

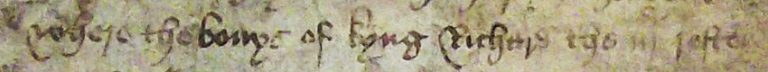

Magnified line from C 1/206/69 ‘..where the bonys of kyng Richard the iijde resten…’ The key line in the case which shows that the site of Richard III’s burial was well-known in the East Midlands in the years immediately after his death.

The modern debate over the intentions of Richard III for his own memorial throws up some interesting questions about how centuries-old evidence can be valuable to very current issues. What evidence is there for Richard’s intentions for his own burial? What is known about his original tomb? To what extent has archival evidence been used to support modern legal arguments? How has this information been used to inform debate in print and online?

Richard’s personal preparation for his burial is not something that can not be known to researchers without an explicit statement in a will or other authenticated personal document – and no such record has come to light, so far. Much survives from Richard’s government, but virtually nothing exists of his private and personal archive as Duke of Gloucester or as King. Any modern researcher must therefore begin to sift evidence that is circumstantial, related, and informative but not specific to the subject of the king’s choice of his burial site and memorial.

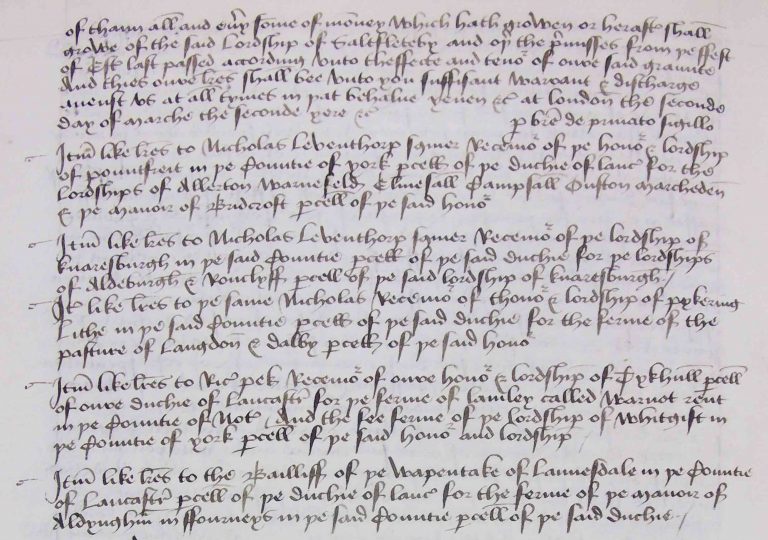

However, evidence from the collections of The National Archives has been used to support the argument that it was the wish of Richard III to be buried in York. In particular, the Plantagenet Alliance has placed considerable emphasis on Richard’s intention to found a college of 100 priests at York Minster to pray for his soul. They emphasise that this suggests he was planning a magnificent royal mausoleum in the cathedral. The most detailed document relating to this endowment was a letter issued on 2 March 1485. It records Richard’s order to a number of church officials to find 100 priests ‘now being of our foundation within the said church’. For this he assigned profits from parts of the main northern estates of his Duchy of Lancaster; including Bolingbroke (Lincolnshire), Pontefract, Knaresborough, Pickering and Tickhill (Yorkshire), and Lonsdale (Lancashire). As patron, he was ‘not willing to have priests unpaid of their wages seeing that by their prayers we trust to be made more acceptable to god and his saints’ (DL 42/20, f.70).

Duchy of Lancaster, enrolment book, Richard III. The crown’s copy of the letter sent under the king’s privy seal to his chief officer at Bolingbroke in Lincolnshire. A separate sheet (not copied into the register) listed which income was to be assigned to fund one hundred priests at York. Dated 2 March 1485. (DL 42/20, fol 70r)

It was certainly a formidable and ambitious enterprise. The licence to the dean of York to fund the priests has been well-known to historians for over thirty years. The grant is mentioned five times in the published edition of Richard III’s book of signet seal letters (British Library Harleian Manuscript 433). These entries show that the king intended the priests to sing in worship of God, the Virgin Mary, St George and St Ninian. The inclusion of the Northumbrian St Ninian has previously been seen as evidence of Richard’s strong relationship with the north. The additional details from the Duchy of Lancaster grant book add a new dimension to this connection, but the entries say nothing directly about Richard’s intention to be buried at York.

The second page of the enrolment. It names the officers in various other northern duchy lordships and the manors and income to be assigned to pay for the livings of the priests at York Minster. (DL 42/20, fol 70v)

Regardless of whether or not Richard did wish to be laid to rest in York Minster, the circumstances of his death created the reality of Richard’s original burial at Leicester. This evidence was used to argue that he should be re-interred in the city – something which fits with archaeological protocol requiring the re-burial of exhumed human remains in the closest consecrated ground to the site where they were found. Yet even at the time this was not without controversy. A brief survey of the histories of his reign reveals that the treatment of Richard’s body was a cause for comment almost from the moment of his death. After the Battle of Bosworth on 22 August 1485, Richard’s mutilated corpse was brought to Leicester slumped over the back of a horse and displayed in the city for two days. One of the first charges levelled against Henry VII by some of Richard’s modern supporters is that once this public demonstration of the death of his rival was finished, Henry ensured that Richard’s body was quickly and unceremoniously buried in a crude grave with no suitable memorial.

However, it is clear from further documentation in The National Archives that even if the burial itself was a quiet affair, Henry VII did commission a formal tomb to mark his predecessor’s resting place. It seems appropriate in light of current events that the construction of this tomb also brought about a legal dispute. In a complaint submitted to the Court of Chancery by Rauff Hill of Nottingham, it is recorded that ‘Walter Hylton, alabasterman […] committed and bargeyned with the right honourable Sir Reynold Bray and Sir Thomas Lovell, knight, to make and cause to be made a Tombe within the Church in Newark of frers In the Towen of Leycestre where the bonys of kyng Richard the iii(de) resten’. For this task, Walter received payment of £20 (C 1/206/69).

Chancery bill of complaint from Ralph Hill of Nottingham. He alleged that Walter Hylton had fraudulently inserted Hill’s name into the indenture and obligations for the construction of King Richard III’s tomb at Leicester. When Hill unknowingly defaulted on the agreements he became liable to powerful counsellors of the new king, Henry VII, for the resulting debts (which he was unable to pay); c. July 1496. (C 1/206/69)

The cost of £20 for the preparation of an alabaster memorial might seem insignificant when compared to the £433 6s 8d initially spent by Henry on the burial of his queen, Elizabeth, in February and March 1503 (which had risen to almost £2400 by May). [ref] 1. British Library, Additional Manuscript 59899, fols 15r and 24r. [/ref] However much Henry might have wished to obliterate Richard III’s memory as a focus for discontent against his own kingship, Richard had always been acknowledged as a ‘king in fact but not by right’ after the Tudor accession. As an anointed ruler and uncle of the first Tudor queen, Richard’s burial place deserved some recognition. This was certainly nothing like the edifice that might have been constructed had Richard died in his bed, but Henry VII could not ignore his rival, even in death. Moreover, because this case came into court on 1 July 1496 it has been presumed that the dispute was directly related to the creation of the tomb.

But there is nothing to suggest that Henry did not commission the tomb early in his reign and that the construction was perhaps held up for a decade by legal wrangling. Had Henry VII delayed the order to construct Richard’s tomb for several years after Bosworth it is difficult to understand why he would have started the project in 1495-6. Although Richard’s short reign has been examined in minute detail, the current attention given to documents relating to his burial and memorial indicates that those who can read and interpret the historical evidence can begin to dominate the discussion of the presentation of the past. It is also true that with figures such as Richard III, only archival collections are likely to continue to yield the kind of information that can challenge long-accepted historical facts or provide new interpretations to change enduring myths.

Historical evidence and thus the interpretation of history cannot be kept churning without continuing archival research and maintenance of the skills needed to recognise the importance of evidence found when rolls, boxes and bundles of paper and parchment are opened. Regardless of how this evidence is then presented, the historical debate can only progress if new evidence is brought to light. Digging around in the archives for documents related to Richard III’s burial might also demonstrate the value of a fresh look at evidence surviving for other historical controversies.

Nothing shows up before 1495 though, when of course we also have the Privy Purse payment to James Keyley of £10 1s for a tomb for the late King Richard – had Henry (or Sir Reginald Bray) found an even cheaper alabaster carver ?

John Ashdown Hill, in his book ‘The Last Days of Richard III’ makes a good case for the tomb being commissioned in the 1490s was linked to the problems Henry VII was having with Perkin Warbeck. The Epitaph associated with the tomb indicated that Richard was King of England and that Henry had defeated him, thus implying that Henry had won the crown by conquest. This would go some way to negating Warbeck’s claim.

[…] Reburial of King Richard III […]

I am just bored to death by where Richard should be buried. The never found him and its a vile hoax on tax payers money. Come clean you idiots and tell people the truth. Education has fallen a new low.

Oh Andrea, give it a rest. Do you trawl the Internet for any mention of Richard III so you can add your completely unsupported theory that the whole dig etc is a hoax? Every site I look at seems to include a post from you about the ‘hoax’ yet in spite of many requests, you have not produced a single piece of evidence to support your case.

Of course it

matters where he is interred. Life thrust many things upon him that were beyond his control, and to have his final wishes ignored is to add insult to injury. Also, the Anglican Church did not exist at the time of his death; given his reputation for piety, I’m sure he would have preferred to have been buried with a full Catholic service. Services are to honor those who have passed and comfort those who mourn them, not to satisfy the economic needs of those who, by chance, happen to be nearby. I very much doubt that he would have cared much for the appearance of the tomb that is planned, given that it is so out of keeping with his time – not to mention that it looks as though it was designed for a church of another denomination.

As to the hoax theory, the only possible motive to do that would also be economic; if that is the case, surely it would have taken place already, long ago.

As a long time ‘Ricardian’ born in Barnard Castle, near to Richard’s Middleham seat and recipient of his patronage, I too regret the bland new memorials to the rediscovered mortal remains of King Richard III – who died heroically when betrayed at Bosworth by treacherous northern lords whose past excesses to his subjects he’d checked.

I also regret the great Cathedral of Leicester, even now, could not find space to display offered gift of Richard III portrait stained-glass commemorative window bearing his arms and motto, made for a much earlier ‘Ricardian’.

Compare these memorials with The Black Prince’s Tomb at Canterbury. No mistaking its importance, no accidental interrment there. Neverthess, I shall make this atheist’s pilgrimage to Leicester.

Keith Piggott

I am sure that his final wish would have to be spared from mutilation on the battle field, but events being as they were this wasn’t to be. In victory he could afford to be placed wherever he desired, in defeat he was given a fitting grave.

There is no doubt in my mind Richard III intended he be buried at York.

I do not know on what authority the “Ministry of Justice” (which sounds very Orwellian to me) ruled when the option was Leicester (a Cathedral only since recent times) – archaeological protocol my foot! – or another legal burial ground.

My ancestor John Milewater of Stoke Edith, Herefordshire, Esquire to the King, Receiver-General, Constable of Bishops Castle, Shrewsbury, and from 1459 keeper of the Duke of York’s 17 castles, was killed at the Battle of Barnet in 1471 fighting for Richard, then Duke of Gloucester (“but he was the King’s man”).

The Duke constructed “a sumptuous and noble” Chantry Chapel on the gravesite and endowed priests for prayers to be said for the dead including John Milewater and named others. His intent to found a college for 100 priests at York to pray for his own soul follows precedent. Please feel free to publish my email address.

The Licence issued by the M of J does actually say ‘(c) The remains shall, no later than 31 August 2014, be deposited at

Jewry Wall Museum or else he reinterred at St Martin’s Cathedral or

in a burial ground in which interments may legally take place. In the

meantime shall be kept safely, privately and decently by the

University of Leicester, Archaeological Services under the control of a

competent member of staff.’’

http://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/burials-and-coroners/Exhumation-licence-12-0159.pdf…

so he doesn’t HAVE to be buried in Leicester at all, the University could very easily have done the right thing and graciously given Richard his ‘homecoming’ as how he himself referred to coming back to Yorkshire. They have behaved appallingly, with the Mayor even saying that ‘’Richard’s connection to York was ‘negligible’ !!!

Leicester have searched for him, found him and honoured him and they now have the opportunity to lay him to rest with the honours that he was denied in death.

The only other alternative for me would have been Westminster Abbey but sadly there was nothing offered by the current Royals or our Government to have Richard laid to rest there.

On another note, I have seen the work underway at the Cathedral, I have been to the Richard III Visitors Centre and in my humble opinion the City of Leicester have behaved admirably in securing a final resting place for a great man. I have sat by his grave and then walked over the road to the Cathedral to see the plans for the re-burial. I felt a great sadness as I looked down into the hastily dug, crude grave but having spent time in the Cathedral I am hopeful that after over 500 years he will be buried with dignity this time.

Its time to stop squabbling and concentrate on making this re-internment the event of the century.

I absolutely agree, C.M. O’Hagan – There is no evidence existing today of where Richard wanted to be buried. The anti-Leicester brigade keep repeating that York is where he wanted to be buried as if it were an incontrovertible fact instead of an inferred assumption based on the fact that he ordered a large chantry chapel to be constructed at York Minster.

This in itself means nothing. Antony Woodville, for example, had several chantry chapels constructed, listed four in his will, but did not ask to be buried in any of them!

The decision was taken, challenged in the High Court and judgement made that Richard should be reburied in Leicester. That should be the end of it. Instead what we get is an endless list of petitions, letter templates to be used to bombard everyone with the remotest connection (and in some cases no connection at all) to the process of the Judicial Review and the reburial which achieves absolutely nothing.

“…not something that can not be known…”

The double negative is really distracting and totally changes the meaning of the sentence.

Can anyone let me know the answer to some academic historical questions on this topic please. I need them for my research on “influence in discovery making”.

1. Who exactly actually discovered the Hill v Hylton document in the National Archives. I notice that on page 130 of his book “The Mythology of Richard III” that John Ashdown-Hill (MBE) (2015) gives the impression – arguably at least in my mere opinion – that it was he. But I found the discovery of the said document in a book published in 1985 – see James Petre (1985) notes it on pages 29-30 in “Richard III Crown and People”.

2. In this blog and elsewhere on the National Archive the litigant is names as Rauff Hill. But Dr James Petre (1985) names him Ralph Hill. Which is the correct name?

3. I notice that a Ralph Hill was Sheriff of Nottingham in 1482 and that Walter Hylton had twice been Mayor of Nottingham (1489, 1496). This would explain (I suppose) why Hill could afford to bring a case before the Chancery Division and would bother to do against Hylton. So the question is: Is Ralph Hill ( Sheriff of Nottingham) the Litigant Raulff Hill?

Any help at all very gratefully appreciated.

No one seems to have noticed that besides the existing knowledge that a Walter Hylton was two times Mayor of Nottingham (1489 and 1496) in this period, the significance of the fact that litigant in the 1496 case of Hill v Hylton was recorded as being named Rauff Hill. My only orignal contributing point here being that in this same period a “Ralph Hill” has been listed on various Internet sites as Sheriff of Nottingham (1481/1482). The point being that expert historians know that the spelling of this forename name would have been spelt in various ways at that time in history. Hence Ralph Hill and Rauff Hill could quite easily be one and the same person.

Either way, I wish to thank expert historians at the National Archives – Dr Sean Cunningham and Dr Laura Tompkins who are authors of this blog- for very kindly explaining to me in an email (because I’m no historian) that one should never rely upon a spelling of a person’s forename, recorded anywhere in this period in our history, as exact and reliable validation of who they were. Because in the 15th century, names were habitually spelt differently by different individuals writing them down. So the Court of Chancery might have simply spelt his name differently, or the same way it was written in Nottingham by himself and others.

Consequently, I would like to assert the following:

if we accept the compelling argument that a “grocer” who had been a former Sheriff of Nottingham would be a particularly likley candidate, powerful and influential and wealthy enough, to sue the serving Mayor of Nottingham, then we have sound reason to assert with some rational confidence that the discovery of the bones of Richard III was in very large part quite probably dependent upon a one time Sheriff of Nottingham suing a two times Mayor of Nottingham for contractual fraud.

I wonder if we can find their graves in Nottingham?

Following on form my last comment. Something profoundly obvious occurred to me after I submitted it. The way forward now, to begin to test the “Richard III and the Sheriff of Nottingham Hypothesis” is to see whether or not there is anything on record regarding Ralph (Rauff) Hill, Sheriff of Nottingham in 1481/1482, having been a grocer before, during his term in office, or after.

I thought you might be interestested to learn that Walter Hylton had been sued over his memorial contract work a decade earlier bay another. Moreover Rauff Hill of Nottingham is almost certainly Ralph Hill the one time Sheriff of Nottingham. I found him i the records of the “St George’s Gild”, with mention of him being the Sheriff holding a joint account with a another who was a “grocer”. Furthermore, the Hill family of Nottingham were also famous “alabaster men”. All this would explain why Hylton was sued and the status of the plaintiff being listed as grocer as well as why he had the power, influence and means to afford to sue in the court of chancery. Most importantly, it explains why his name would be on a contract for an alabaster monument.

All the independently verifiable details are here: https://www.bestthinking.com/thinkers/science/social_sciences/sociology/mike-sutton?tab=blog&blogpostid=24085

I am currently reading ‘The The Account Books of the Gilds of St. George and of St. Mary in the Church of St. Peter, Nottingham’ in the form of a self-published in 1939 transcription by R.F.B Hodgkinson. printed by Thomas Foreman and Son Ltd and Edited and introduced by Professor L.V.D Owen of University College Nottingham

As I have added as an October 4th postscript to my above referenced blog post on this topic Something of importance comes to light on page 58 of this publication that sheds some interesting new light on the subject matter of Richard III’s tomb.

Then on page 58 we find something most interesting about Greyfriars and these accounts of the Gild of St George in the Church of St Peter Nottingham. We must remember that these Gilds could only be established with Royal assent and that they were used to perform may of the offices that today are controlled by central and local government institutions. For example, they were used pay taxes to the crown via their membership. The text on page 58 suggests that in 1494 Walter Hylton legitimately used the Gild money to make or more likely, perhaps, repair the then existing monument for Richard III at Greyfriars in Leicester. this is the year before walter Hylton was sued by Rauff Hill. It looks like the Gild agreed to pay for the monument via Walter Hylton – or else that Hylton was – as Alderman – making an executive decision in that regard. This strongly suggests that the Ralph Hill, Chamberlain of the same Gild and one time Sheriff of Nottingham – as evidenced in the accounts of the Gild – a decade earlier in circa 1482 – 84 is the same Rauff Hill the plaintiff in Hill v Hylton.

The account list numerous payments made directly to Walter Hylton amounting to £4,.10 shillings and 7 pence. Another sum amounting to £7, 7 shillings and 7 pence. The whole amounting to £11 18 shillings and 2 pence. Then continues most alluringly and ends with a cliffhanger with regard to this money. Hodgkinson (1939) writes on page 5*

‘Item thereof ye said Walter paid to reparacion of ye grey Frere…….. [the bottom of this leaf has been cut and so half of the next line and the whole of the following ones are obliterated.]

The telling questions here are

(1) “Who obliterated the rest of the orignal Nottingham Gild document and why!”

(2) Why does it say repair “reparacion”? This is rather interesting, because current knowledge has it that the Hill v Hylton lawsuit is evidence that the monument was first commissioned to be built by Henry VII some nine years after 1485 to befit the prior monarch whom his forces killed at the Battle of Bosworth. The evidence here, however, is indicative that a memorial may just possibly have already existed, been somehow damaged, and that Hylton was contracted to repair it.

However, this is a bold assertion and tentative hypothesis made on the basis of one word alone. I suppose much will rest upon how historians decide to understand and so interpret the use of the word “reparacion” in the middle ages.

I notice that Ashdown-Hill (2013) wrote:

” …no other records of Richard III’s tomb in Leicester and dating from the period 1490 to 1500 are currently extant.’

In fact, it seems that another record is now extant. And it is in the Nottingham Archives!