Indian Philosopher Swami Sivananda once said: A mountain is composed of tiny grains of earth. The ocean is made up of tiny drops of water. Even so, life is but an endless series of little details, actions, speeches, and thoughts. And the consequences, whether good or bad, of even the least of them are far-reaching.

This blog is dedicated to Emma Haden, about whom I know very little. But I do know that her life changed terribly on 25 July 1903 when a farmer lost his temper, and she lost her husband.

When looking though old documents it is easy to forget that every name we come across was a real person, with family members, feelings, ideas and lives to lead. In the excitement of building your family tree it is so easy to turn the page, or click the mouse, and miss a story. We move on, looking for the next relative, collecting names without stopping to consider each person’s circumstances, their world, how they lived and the people around them.

Emma Haden lived in Audley Road, Alsager in Cheshire, near Stoke on Trent. She was 42 years old in 1903 and she lived with her husband of 17 years Charles Henry Haden, and their five children. Charles worked for the North Staffordshire Railway Company as an engine driver. It is likely that he had served a number of years with them, working his way up from cleaner to fireman, and finally to engine driver.

25 July had been a normal working day for him. At 19:15 he brought his goods train to rest at Chatterley, about three miles from Alsager, leaving the rear part of the train across an ‘occupation crossing’ on some farmland. This may not have been the first time that this had happened because the farmer was not pleased that access to part of his land was blocked, and he made his way down to remonstrate with the railwaymen.

Emma’s closest railway station was Alsager Station (catalogue reference: RAIL 532/48)

The Railway Department sub-inspector’s report to the Board of Trade regarding this incident (RAIL 1053/92/479) states that the farmer walked down into the yard in a threatening manner, and actually took hold of Yard Foreman Thomas Hemming.

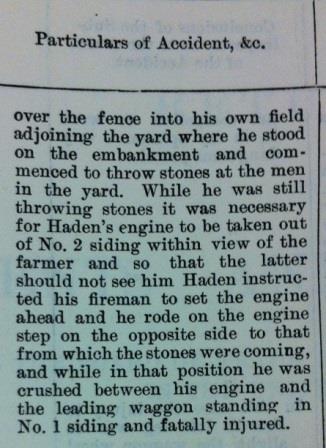

Charles, who was standing on the footplate of his engine, saw what was happening and immediately ran to help his colleague. At this point the farmer took off his coat and challenged Charles to a fight, and started throwing punches. Charles fought back and several blows were exchanged before Charles ran back to his engine. The farmer climbed over the fence into his own field, from where, standing on an embankment, he proceeded to throw stones at the men in the yard. Charles needed to move his engine out of the siding, so he instructed his fireman to move the train forward. He rode on the engine step on the opposite side to that from which the stones were coming, using the engine as a shield.

As he rode on the side of the engine, trying to protect himself from the stones, he failed to notice a wagon standing in the adjacent siding. As his engine moved forward he was crushed between it and the wagon. He was so badly injured that he died shortly afterwards.

Accident report (catalogue reference: RAIL 1053/92)

This ‘accident’ is included in the Board of Trade Sub-Inspector’s Accident Reports, which are now searchable on Discovery, our catalogue for the period 1900-1910, following a cataloguing project overseen by myself, with the help of many members of the Advice and Records Knowledge Department. The sub-inspectors reported on the smaller injuries to individual people rather than the large scale train crashes covered by the higher ranking inspecting officers. The reports can include such minor accidents as railwaymen tripping over points levers, or catching their thumbs between two buffers. But they also include men being killed, or sustaining major injuries such as losing limbs when falling under moving wagons. Many of the accidents result in fatalities, and the men involved can be as young as 15 – young boys employed as Assistant Horse Lads, for example. Each report is a detailed snapshot of an incident in an ordinary working man’s life.

The report on this particular incident blamed Thomas Hemming, the Yardman, for leaving the wagon against which Charles was crushed too close to a ‘fouling point’ – a place where vehicles can collide if left too close to a junction.

The farmer who lost his temper is not named in the report, and neither is Charles’ wife Emma, who was probably at home with the children that summer Saturday evening, when she lost her husband because someone threw some stones three miles from her house.

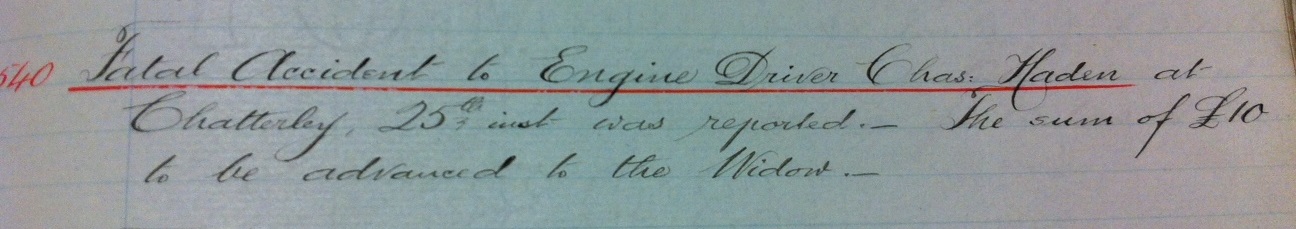

Entry from the North Staffordshire Railway Company Traffic and Finance Committee Minutes 1903 (catalogue reference: RAIL 532/21)

[…] Indian Philosopher Swami Sivananda once said: A mountain is composed of tiny grains of earth. The ocean is made up of tiny drops of water. Even so, life is but… Go to Source […]

Hi, how do I leave an incident for posterity? Please let me know if this should be posted elsewhere.

My wifes grandfather was killed in a railway incident in 1925. ‘Tich’ Riggott was one of a large party of fans from Chesterfield, Derbys, going to Wembley for the Cup Final between Sheffield and Cardiff. As the special train pulled into Grassmoor Station (long gone, just south of Chesterfield) there was a rush to board. A few minutes later as the train pulled out, ‘Tich’ Riggott was dead on the tracks, having been run over. The carriages had no corridors so none of his mates missed him until they got off at the other end. Even then, in the excitement of the occasion he wasn’t searched for. Most of the fans didn’t know what had happened until they got back to Chesterfield. No message of the fatality had been sent on ahead to inform the train crew. His wife had died a few years earlier and he left behind 5 orphans. They were farmed out to relatives. A daily newspaper at the time got up a collection and it was put into trust where the relatives got an amount each week for the kids keep to the age of sixteen. Unfortunately none of the five were really wanted (they were kept because of the money) and were treated as nothing more than slaves. My father-in-law, John Riggott, from the age of five had to do all the demeaning tasks like empty all the mornings chamber pots, clean the rest of the families shoes, carry the coal in…. On his sixteenth birthday he walked out, as had all his siblings with the other families. Being the youngest, John had endured it most, for eleven years. My heart hurts when I think of it, he was such a good man, quite religious he was a Sunday School teacher for some years. He’s dead now. A coal miner most of his working life and a Private in the Notts and Jotts Regiment in WW2. He admitted to telling one serious lie…. he promised the Priest that he would allow any children, of his catholic wife to be, sweet Eva O’Brien, to be brought up catholic. They never were.

Interestingly, though, there was a North Staffordshire Railway engine driver called C. H. Haden still alive a few years later, when the “Staffordshire Sentinel” of 26-4-1911, (p3) records him making a donation to the paper’s appeal to raise money for an extension to the local hospital, the North Staffordshire Infirmary. This is so far the only other Haden I have come across who worked for the line, so he might be a relative.

One of my ancestors was hit by a train at a level crossing in Yorkshire. It was around 1800. Her name was Grace Cunningham. She was quite elderly and I guess she just didn’t hear it coming. I did see this story in print but now can’t find it. Help

Hi Tracy,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

Best regards,

Liz.