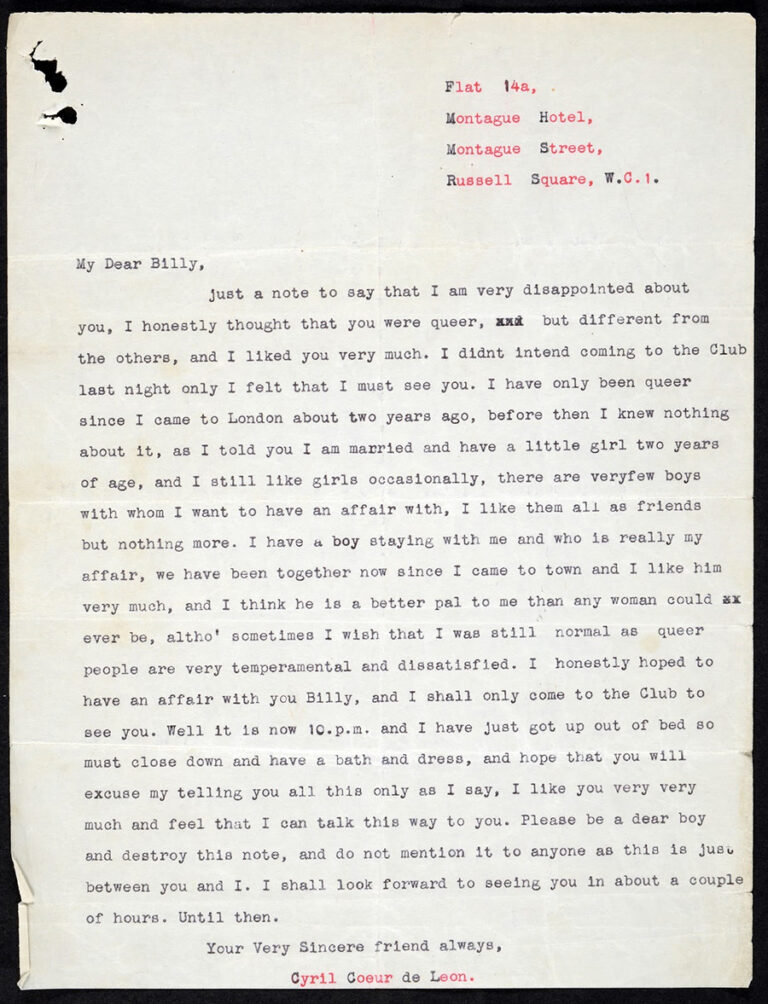

‘I honestly thought you were queer, but different from the others, and I liked you very much […] I have only been queer since I came to London about two years ago, before then I knew nothing about it.’

Cyril writing to Billy, 1934. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/758

Researching LGBTQ+ history can be particularly difficult considering that much of the terminology we use today would not have been available to people in the past. Many archives appear to lack material that include the identifiers Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Trans, because these labels did not always exist. But as time progresses and our knowledge of LGBT history broadens, our language and terminology also change.

In this blog post, I will be tracing the history of the word ‘Queer’, looking at the term’s contentious history, while also exploring how more recently it has been reclaimed by people within the LGBTQ+ community – becoming a label that encompasses the fluidity of identity, or the lack of alternative suitable terminology.

It was not until 1894 that the term ‘Queer’ is thought to have been used in relation to a person’s identity. During the infamous 1895 trial of Oscar Wilde, a letter from the Marquis of Queensberry detailing his disgust at Wilde’s relationship with his son Lord Alfred Douglas was read aloud in court, in which he refers to Wilde and other homosexual men of the time as ‘Snob Queers’. The letter in question along with transcripts from the trial have sadly not survived, but The National Archives has a number of records relating to the trials, imprisonment and death of Oscar Wilde.

It is believed that the slur ‘Queer’ would have originated around this time, and this would have only been enhanced further by the publicity and notoriety surrounding Wilde and the criminal trial. In particular, American newspapers picked up on Queensberry’s use of the word and adopted it themselves. However, The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang (1937) notes that it wasn’t until 1914 that ‘queer – a derogatory adjective meaning homosexual’ – was being used more commonly in society (p. 524).

Considering its evidently offensive and degrading origins many people dislike the term and take issue with its use as it still retains cultural remnants of anti-LGBT or homophobic sentiments.

‘queer adjective 1. Homosexual. Derogatory from the outside, not from within. US, 1914′

(The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang, p. 524)

The dictionary also notes that as a noun ‘Queer’ can also refer to ‘a homosexual man or a lesbian. Usually a pejorative, but also a male homosexual term of self-reference within the gay underground and subculture’ (p. 524, own emphasis). In fact, even as an adjective the dictionary states that ‘Queer’ is considered ‘derogatory from the outside, not from within’ (p. 524, own emphasis). Thus, despite the term’s own history as a slur, many individuals have claimed the word for themselves, finding it an appropriate label for self-identifying.

In a letter held at The National Archives, discovered following a raid connected to The Caravan Club (a ‘disorderly house’ of ‘male prostitutes’ – MEPO 3/758), Cyril Coeur de Leon uses ‘Queer’ as a form of self-identification. Writing to the owner of the Caravan Club (Billy), Cyril explains, ‘I have only been queer since I came to London about two years ago, before then I knew nothing about it, as I told you I am married and have a little girl two years of age, and I still like girls occasionally, there are very few boys with whom I want to have an affair with’ (MEPO 3/758).

Cyril’s use of ‘Queer’ to describe his sexuality is surprising and arguably modern, for it was not until much later – towards the end of the 20th century and start of the 21st – that the term was used to describe gender or sexual fluidity. Other documents obtained in similar raids across London, held at The National Archives, further demonstrate the use of ‘Queer’ as a self-identifier within the community.

In the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, activists and community groups were reclaiming the word ‘Queer’, and in popular culture the term was becoming increasingly more commonplace. For example, in 1990 American HIV/AIDS activists (formally known as ACT UP) became Queer Nation, a movement dedicated to fighting for LGBT rights and visibility. In 1999 ‘Queer As Folk’ aired on mainstream British television, and in the US in 2003 ‘Queer Eye’ appeared on screens, recast 15 years later and available on one of the world’s largest content-streaming platforms.

At Pride events and marches, or as part of campaigns for LGBTQ+ visibility and equality, one will often see badges, t-shirts and banners proudly emblazoned with the word ‘Queer’. Some of the pictures included in this post are from the Bishopsgate Institute’s ‘Lesbian and Gay Newsmedia Archive’ (REF:QMB/10), and in their LGBTQ+ archive you can find a vast array of ‘Queer’ ephemera and memorabilia from over the years.

While not everyone feels as though they can reclaim the word ‘Queer’, given the years with which it held such negative connotations, it has fast become an umbrella term for the LGBT community, encompassing within it a variety of non-heteronormative identities and sexualities. Subsequently, ‘Queer’ is also commonly used today as an identifier itself for individuals, like Cyril perhaps, who did not identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or trans. The Q in LGBTQIA+ is often regarded as ‘Queer’ or ‘Questioning’ and is a familiar addition to the acronym.

Tracing the history of the word ‘Queer’ over the last few centuries demonstrates not only the ways in which the term itself has changed – its use and its meaning – but it also highlights societal changes towards gender and sexuality. Letters like Cyril’s or the one read aloud during the Queensberry trials, as well as ephemera and other archival items, are a crucial part of a broader understanding of ‘Queer’ – of queer history – for they help us uncover and understand queer lives, queer experiences, and the treatment of those that may have identified as ‘Queer’.

Thank you to the Bishopsgate Institute for the use of the images from their LGBTQ+ Archive.

If you yourself are interested in how to research archival materials relating to gender and sexuality, be sure to read The National Archives’ guidance on how to look for records of gay, lesbian and bisexual history.

Works cited

Murray, Douglas. ‘Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas’. London, Hodder & Stoughton, 2000

Partridge, Eric. ‘A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English: Colloquialisms and Catchphrases, Solecisms and Catechesis, Nicknames, Vulgarisms and Such Americanisms as Have Been Naturalized’. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982

Seems like an invasion of Cyril Coeur de Leon’s privacy.

In the Sixties, the description was “queer as a bottle of crisps” What you did with the bottle nobody said and we didn’t know or care.

This article is called the history or queer, doesn’t describe much history, did I miss something ?

A small corrigendum: it’s the Marquess of Queensberry, not “Queensbury”.

Thanks Olivier – we’ve made that correction.

There is no such thing as the LGBT+ Community- there are communities but never one community. The diversity and range of people who can be labelled as LGBT+ is so vast it will never be seen as one community. No one talks of the ‘black community’ or the ‘white community’.

Interesting article, but not really a history of the word if it only covers 2 instances of its use in the late 1800s/early 1900s and then vaguely refers to the 80s/90s/00s lol. What about the 100 years in between?

Please check the ethnograpich work of George Chauncey who cites use of the word queer among men in 1930s New York. The term has been used as a self-identifier far before the latter part of the 20th century.

This comment is in regards to Dr. Clifford Williams comment beginning, “There is no such thing as the LGBT+ Community . . . ” I think he makes a compelling point. Unity withing the “LGBT (QIA, etc.) is an illusion, I’m afraid. People who are part of the world of same-sex relationships are far more diverse than many realize because so many are invisible socially speaking, such as those in heterosexual marriages. Furthermore, even among the world of gay men, there are divisions regarding race or color. In Washington, DC for instance, there came a time when African Americans felt less than welcome in Gay Pride and therefore founded Black Gay Pride, which now takes place in a number of cities. Ageism and lookism penetrates gay male society so completely that it may be difficult for many to see. One gets the impression that according to some it’s OK to be gay as long as you’re handsome, young (between 18 and 40) and have an athletic build. If you don’t fit within these parameters it’s incredible how utterly one can be excluded from gay social groups.

Among straight people and kids, he term was a slur until the 1980s, when it was reclaimed (slowly) as a useful “umbrella” way to include gay men and women, bisexuals and anyone who is hard to pin down sexually.

in The Elizabethan Underworld by Gamini Salgado ‘queer-bird’ is listed as meaning jail-bird.

Queer is also listed as;

queer-ken meaning prison

Queer meaning paltry or bad.

Queer-cuffin as Justice of the Peace!

Any thoughts?

In the early 1990s OLGA (The Olaf Lesbian Gay Alliance, at St. Olaf College) was very happy about one simple umbrella for all, and all our hopes were going for “queer.”

I am researching the origin of ‘Friends of Dorothy’ as a reference to gay men. Obviously, the Dorothy is the fictional character in Frank L Baum’s Oz books. Wikipedia suggests “Some believe that it is derived from The Road to Oz (1909), a sequel to the first novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). The book introduces readers to Polychrome who, upon meeting Dorothy’s travelling companions, exclaims, “You have some queer friends, Dorothy”, and she replies, “The queerness doesn’t matter, so long as they’re friends.” What strikes me about this is that 1909 is before the many references to ‘Queer’ as ‘gay’ mentioned in the article here. I would guess that queer is being used by Baum as simply meaning odd or unusual. So this particular history may be a retrospective claiming of the word queer. There are other origins of the ‘Friends of Dorothy’ – one that it was a code phrase to enter the parties held by Dorothy Parker – this may or may not be playing on the fictional name Dorothy