The night of 24-25 March 2020 marks the 76th anniversary of the real Great Escape when, in 1944, 76 British and Allied officers and airmen escaped from prisoner of war (POW) camp Stalag Luft III, situated near the town of Zagan in Poland.

If you’ve watched the film The Great Escape, with Steve McQueen and his motorbike, or read books about the real, brave prisoners of war that escaped, you could be forgiven for thinking that escapees during the Second World War were all officers and all from German POW camps. In fact, many successful escapes to the UK were not from German camps: they were pilots and air crew who crashed in occupied Belgium or France, evaded capture, were hidden by brave civilians and led across occupied territory to Spain.

In Italy many escaped to the Allied lines from Italian-held POW camps in the chaos following the Italian surrender. But for Allied prisoners held in German POW camps in the East or in occupied Poland, it was very hard to escape across such vast, hostile territory. Yet of the thousands held there, some did try, and a few made it home – both officers and other ranks.

Unlike officers and Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs), POW soldiers were required to work and often endured harsher conditions and poorer food. Prisoners would be sent out to work in an ‘Arbeitskommando’ – ‘ARB KDO’ in the record cards in the record series WO 416 – to farms, mines, factories or building projects.

Cards were sometimes stamped with a note that the prisoner had been told not to fraternise with German women or with civilians generally. Going out to work offered opportunities to escape and sometimes better food, but work left them little time to plan and gather materials. Some camp escape committees prioritised officers and senior NCOs with escape support. For everyone, escaping was very dangerous, and you could be shot for trying. And getting out was often only the beginning of your problems.

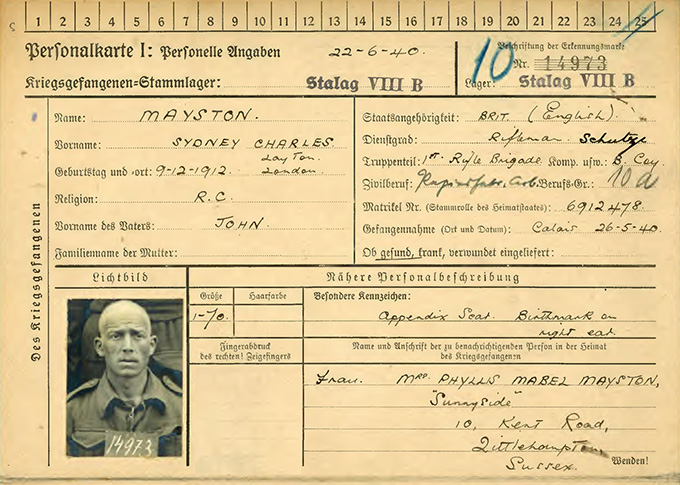

In the records of Charles Sydney Maystom (WO 416/251/332) is a letter from the Abwehr to the Camp Commander informing him that Maystom and three other prisoners were to lose all their rights as NCOs, as their pay books had been examined and pages had been deliberately cut out to hide their rank!

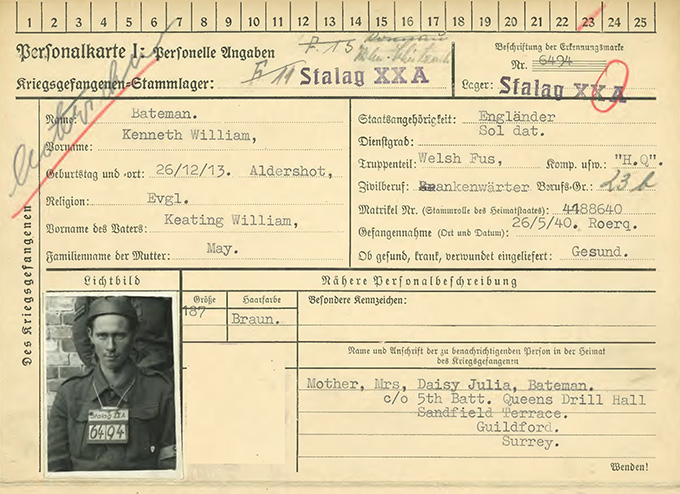

Bandsman Kenneth William Bateman of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers was captured in France in May 1940 and taken to Stalag XXA at Thorn (modern Torun, Poland). Conditions were very bad with harsh discipline and poor food. Between July and October 1940, 38 men died of dysentery and other diseases such as scabies and diphtheria were also rife.

In October 1940, he and another private managed to escape from their work camp at Kulm (Chermno) over the lavatory wall. They were guided by Polish resistance to the border with Russia but captured by the Red Army. They were held in terrible conditions in various prisons until the German invasion of the Soviet Union turned the Russians into Allies. In July 1941, they were moved to a hotel in Moscow and released to the British authorities. (See WO 208/3305/462 and WO 416/22/137).

A similar fate befell Corporal William Corkery and Private Harold Doyle. Both cooks in peacetime, they were captured in 1940 – Corkery in Norway, and Doyle in France. Both were sent via Stalag XXA to Winduga work camp.

In December 1940 they escaped at night from the canteen. Helped by Polish farmers, they made it to Warsaw and then to the frontier where they were seized by the Russians and thrown into jail for months, before they too were moved to a Moscow hotel and then released in July 1941 to the British. All four were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for their escapes. (See WO 416/77/428, WO 416/102/88, WO 208/3305/460 and WO 208/3305/461).

Gunner Cyril Edgar Harrison of the Royal Artillery, captured in France in 1940, was sent to several ‘Oflags’ (officers’ camps) where he served as an orderly and worked as a tailor. He secretly helped in a tunnel and also made German uniforms used in others’ escapes. Then he was moved to Stalag VIIIB at Lamsdorf (now modern Lambinowice in Silesia) where he worked at various nearby work camps. Three times he escaped, but each time was recaptured. Finally, he teamed up with Sergeant Bruce Joshua Crowley of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, when they met at the Breslau gas works camp.

Crowley had escaped several times, first in Greece and then in Germany, before being brought to Lamsdorf. As an NCO, Crowley was not obliged to work but had agreed to do so, as he reckoned it would give him a better chance of escape. The pair escaped from Breslau in September 1943, having acquired civilian clothes from a Ukrainian worker and a railway timetable from a local Polish worker. They travelled by train and tram to the coast and were helped by French workers to smuggle on board a Swedish ship to Stockholm, where they were delivered to the British authorities. (See WO 416/164/386, WO 416/84/32, WO 208/3315/60 and WO 208/3316/1523).

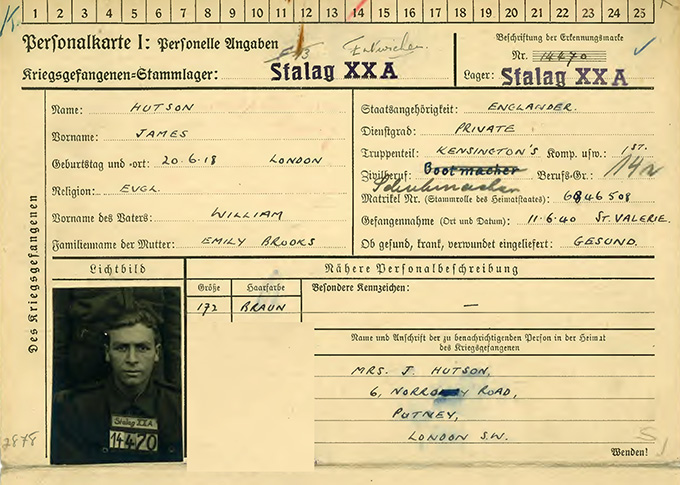

Perhaps the most curious tale is that of Private James Thomas Hutson and Signalman John Glancy. They were both captured in France in 1940 and held in Stalag XXA. They had been given the job of caring for 200 Angora rabbits held in a hut near the Commandant’s quarters. This privileged access enabled them to help others to escape and then in turn to escape themselves. Both their cards were stamped with the order not to fraternise with civilians, and handwritten in German on both cards was the comment that they had refused to sign it! (See WO 416/139/445 and WO 416/190/406).

In October 1943, they escaped from the rabbit hut, together with two officers, who they had disguised as privates in order to get to the hut. The two officers were prolific escapers but had newly arrived from POW camp in Italy and benefited from Glancy and Hutson’s local connections with the Polish underground. All four then escaped from the hut in civilian clothes.

After some narrow escapes, thanks to Polish help, all four made it to Gdynia, were smuggled onto a Swedish ship and handed over to the British Embassy in Stockholm, before being flown back to RAF Leuchars in Scotland. Glancy and Hutson were recommended for the Military Medal for their efforts. (See WO 208/3316/1514 and WO 208/3316/1522).

This is the fifth blog focusing on the project to catalogue the series of records WO 416, consisting of an estimated 200,000 records of individuals captured in German occupied territory during the Second World War. These individuals were primarily Allied service men (including Canadians, South Africans, Australians and New Zealanders) but there were also several hundred British and Allied civilians and a few female nurses. You can read about other elements of the collection from the staff and volunteers helping to make these records available here, here, here, and finally here.

How is it that my relative who was at Stalag VIII-B and Arbeits Commando E243 (Breslau gas works) has no POW card or MI9 Interrogation Card?

Have postcard of private john watson at stammlager xxa 1942 would like to reunite with said relatives .

Ref previous message poe no 18834?