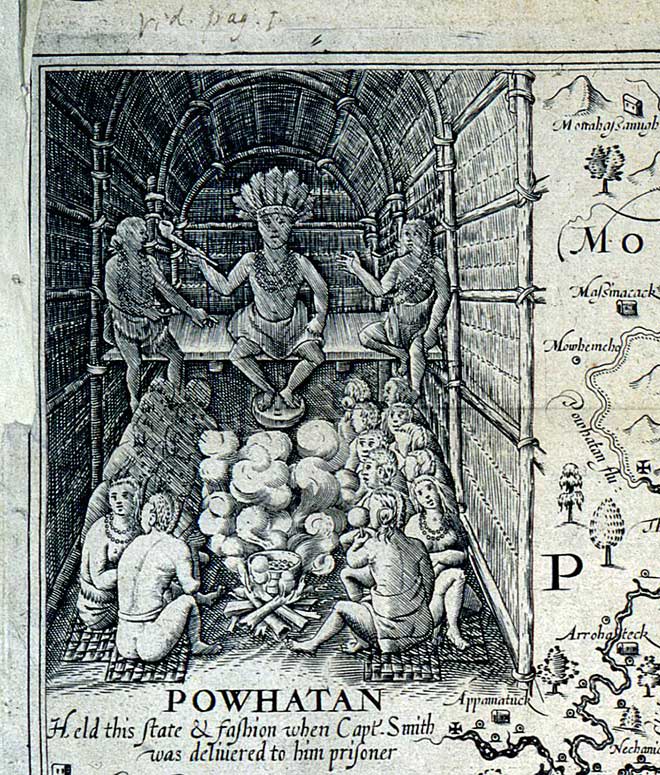

Representation of Chief Powhatan’s court taken from print of Captain John Smith’s map of Virginia made in 1608. Pocahontas may be one of the two figures either side of the chief (catalogue reference: MPG 1/284)

This month sees the 400th anniversary of the visit of Pocahontas, the Algonquian Indian princess, to London with her English husband, young son and a group of fellow countrymen and women. They crossed the Atlantic at the request of the Virginia Company to encourage the English to invest in the colony.

Pocahontas is remembered today as the Native American child who made friends with Captain John Smith in 1607 and whose subsequent interaction with the new English arrivals eventually led to a period of peace between her people and the colonists. She converted to Christianity and married John Rolfe in 1614, changing her name to Rebecca Rolfe.

Related to and representing a foreign ruler, but speaking English and appearing in English dress, for people in 17th century England Pocahontas combined the exotic with the familiar. Her story, laced with myth, has been retold many times over the intervening centuries and she remains a key figure in American history.

We have surprisingly few references to her visit in the public records, but here are a few of those which do survive.

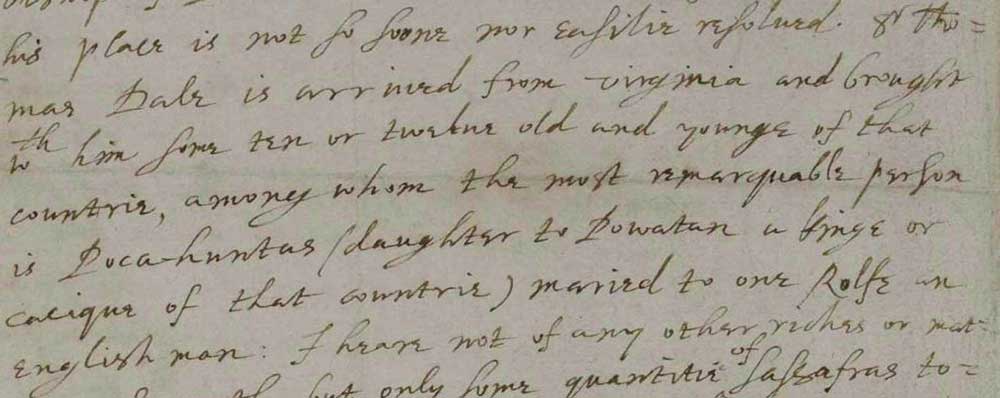

The first mention of the visit is dated 22 June 1616. The prolific letter writer John Chamberlain reported that Sir Thomas Dale, Deputy Governor of the colony, had brought from Virginia:

‘some ten or twelve old and younge of that countrie, among whom the most remarquable person is Poca-huntas (daughter to Powatan a kinge or cacique of that countrie) maried to one Rolfe an English man…’

He went on to report that the country promised well, but no present profit was expected.

Letter (excerpt) from John Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton, dated 22 June 1616 (catalogue reference: SP 14/87, f.135v)

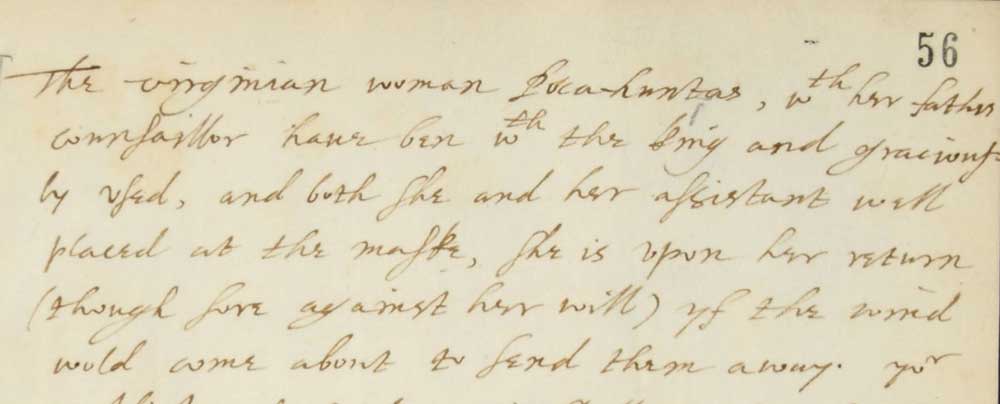

John Chamberlain wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton about Pocahontas again on 18 January 1617. Carleton was the English ambassador in The Hague and Chamberlain wrote to him regularly to tell him the news he had gathered from walking around London and, in particular, from frequenting the centre of gossip which was St Paul’s Cathedral.

In this letter, Chamberlain noted that Pocahontas had recently attended a masque hosted by King James I. Ben Jonson’s ‘Vision of Delight’ was performed before the court on Twelfth Night 1617 and at it Pocahontas was accorded the status of a visiting ambassador. She was also received on separate occasions by the Queen and by the Bishop of London.

‘The virginian woman Poca-huntas, w[i]th her father[‘s] counsaillor have ben w[i]th the king and gracioussly used, and both she and her assistant well placed at the maske, she is upon her return (though sore against her will) yf the wind wold come about to send them away.’

Letter (excerpt) from John Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton dated 18 January 1617 (catalogue reference: SP 14/90, f.56)

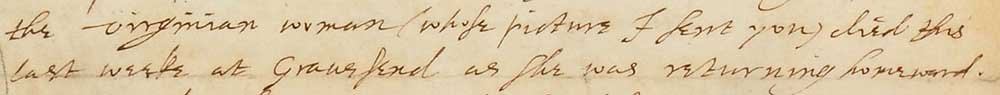

The wind took its time in changing direction, as the party did not depart from the port of London until March 1617. Shortly afterwards though, Pocahontas was taken ill and the ship docked at Gravesend in Kent, where she died and was buried. She is thought to have been only 21 years old.

John Chamberlain reported the news without any emotion: ‘…the virginian woman (whose picture I sent you) died this last weeke as she was returning homeward.’

Letter (excerpt) from John Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton, dated 29 March 1617 (catalogue reference: SP 14/90, f.250v)

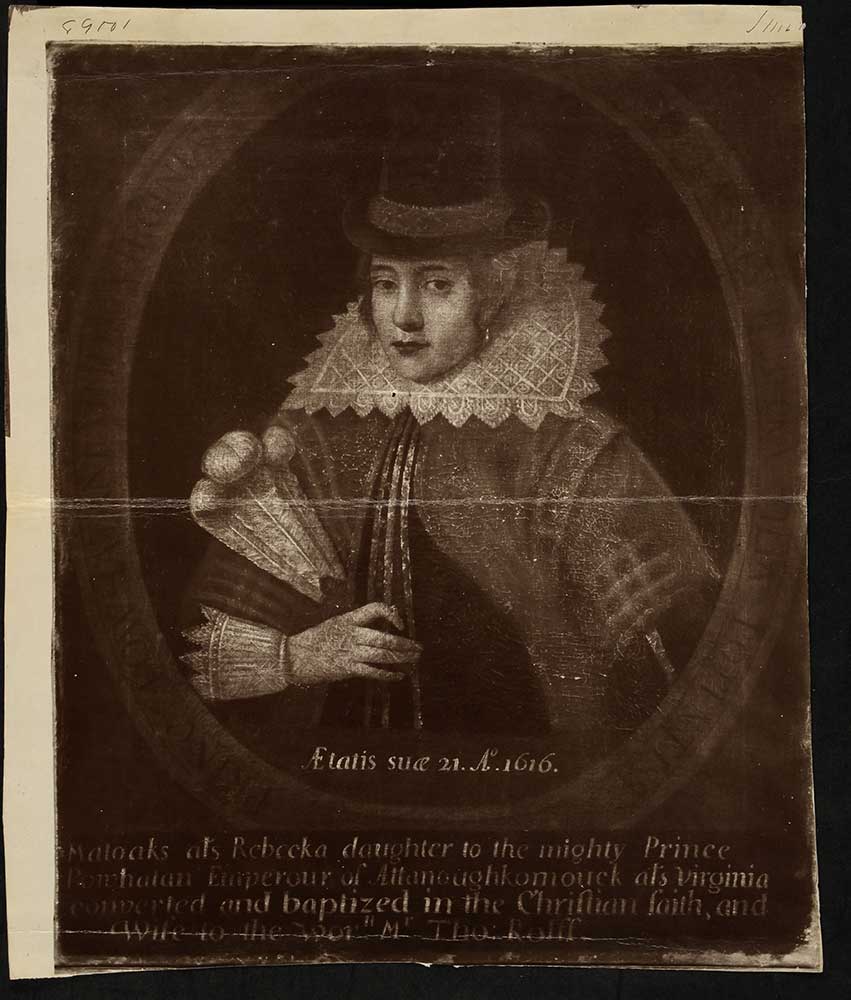

Pocahontas’s story in the archives does not end with her death. The engraved picture of her by Simon de Passe, produced and circulated during her visit to London, formed the basis of several subsequent paintings. A photograph of one of these, taken in 1884, is in our copyright records. The painting itself is now in the collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC.

Photograph (registered for copyright purposes in Norfolk in 1884) of a 17th-century painting of Pocahontas based on the published engraving of her image (catalogue reference: COPY 1/369/171)

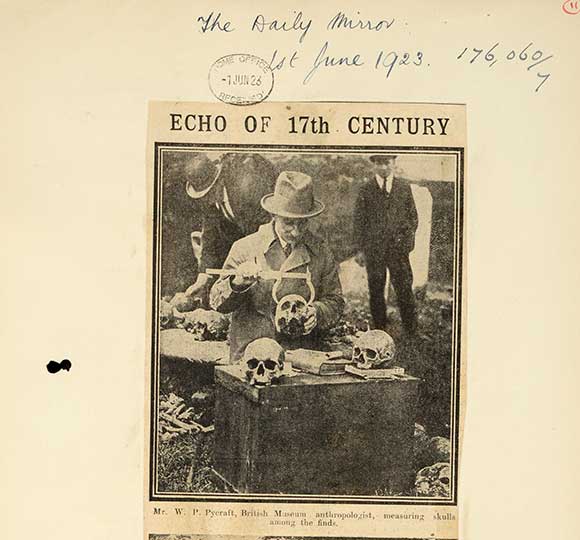

An early 20th century Home Office file (HO 45/14558) ends the story of Pocahontas at The National Archives. In 1923, probably inspired by the results of excavations of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt, the English Speaking Union applied to exhume Pocahontas from the graveyard in Gravesend, hoping to be able to repatriate her remains if they were found. One representative, Edward Page Gaston, lamented the fact that ‘our American Princess has slept for centuries in an unknown grave in this distant land’. The exhumation attempt was unsuccessful and the extensive and mainly negative press commentary clearly exasperated the Home Office.

Newspaper cutting from the Daily Mirror, 1 June 1923, documenting the search for the remains of Pocahontas (catalogue reference: HO 45/14558)

The Daily Express had its own inventive scoop with the story that:

‘Princess Pocahontas, the pretty Red Indian princess who married an Englishman and was buried at Gravesend after living happily with him in this country for many years, may have been sold to a rag and bone man for a balloon’.

However, the tone of the rest of the press tended to match that of the Evening News which stated ‘This is a meddling curiosity, a peeping sacrilege’.

A display of facsimiles of these documents will be viewable in the Keeper’s Gallery at Kew for the next six months.

If you want to know more about records of the early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans, see our Education resource on Native North Americans.

With modern technology in this century, will another attempt be made to find her remains in Gravesend?

In 1997 I met a gentleman called Mr Vic Lawrence who retired locally to Snettisham whose house as a child when he was at Gravesend Primary School overlooked the church yard when many graves were dug up in about 1938 trying to find Princess Pocahontas’ burial site he watched with his younger sister. They had been taught this important history at school -but the church has burned down several times in the past 450 years if you check their past St Georges church history . So it was not easy to pin point exactly where the old Chancel of the second church was standing where she was buried on March 21st 1617 and they soon realised it was an impossible task and was disturbing the sacred burial sites of so many other families that is not good.In about 2002 there was another request to the vicar to try searching again but it was declined for similar reasons. It would be interesting to find other members of her close family as well as her son Thomas Rolfe who died in about 1668 near Kippax Plantation near his home at Varina Henricho who has a Hickory Memorial Tree still growing planted close to where it is thought he was buried who is the great great uncle to the first President George Washington through his first marriage at Clerkenwell to Elisabeth Washington in about 1632 who died at the birth of their daughter Anne who survived and was raised by Rolfe relatives in England and inherited her mothers pearl wedding present ear rings a gift from her famous father Chief Powhatan who did have an oak memorial tree planted in Virginia . Thomas Rolfe’s father John Rolfe from Heacham who married Princess Pocahontas on April 5th 1614 at Jamestown’s first church also has no known burial site or even a plaque who died in March 1622 on or just before the Henricho Good Friday massacre yet he was famous because he was Americas First Entrepreneur to start the first commercial tobacco plantation that saved their lives ‘financially’ via its hugely successful trade to Europe thanks to her family’s help who shared new ways to dry and package tobacco in their sailing ships .They would not have known tobacco nicotine is addictive and can cause lung cancer when smoked or that later these farms and plantations took on new workers from overseas -some who were later bought in as slaves .But now these tobacco plants in USA and Germany are being used to make new drugs for treating Ebola-the ZMAPP drug and for Cancer-for Flu-for Malaria and Parkinson’s and other Neurological diseases -that could save millions of lives if these work successfully. So I hope that in this 400th Anniversary year of their visit to England including Cornwall Indian Queen village (re-named after her stay) to Savage Inn renamed Belle Sauvage Inn near St Pauls Cathedral London and to Boston with another inn renamed after her visit INDIAN QUEEN as she was to succeed her father as the next Queen when he died in 1618 and to Heacham Hall where ‘legend’ says she planted the old mulberry tree in 1617 growing at the now Manor Hotel that there will be a new Memorial tree planted for all of this important family in Heacham next to their Rolfe special walled family burial garden where 45 relatives are buried -including famous heads of the Royal Navy and Admiralty .

The Pocahontas story is alive and growing. If you go to http://www.visitgravesend.co.uk and look at the Pocahontas 400 section you will see a whole series of events and gatherings marking the 400th anniversary of her death on 21 March, 1617.

I have been amazed at how well known the story is not from just local people but from all over the World. Although this may well be from the Pocahontas of Disney story, there are regular visitors to St George’s Church where the factual, historal story is told.

This young, Native American woman from the ‘naturals’ as they were called by the settlers continues to bring people together.

I have sought and found the last burial place of pocahontas but dont know what i should do with the imformation as so many people are involved she sleeps peacefully now .

[…] sore against her will.” The original passage in Chamberlain’s handwriting is reproduced in a blog post from the National Archives. See also The Pocahontas Archive at Lehigh […]

I am trying to clarify if Pocahontas arrived from America via Portsmouth or Plymouth UK on route to London? Portsmouth would make more sense if going straight to London? There is some discrepancy online with both ports being referred to. Is there proof of either? Any help and correct reference much appreciated.