‘Every precaution must be taken to ensure that his identity shall never become known.’

On Friday 15 October 1920, a mere 27 days before Armistice Day, the British Cabinet considered a proposal sent by the Dean of Westminster, Herbert Ryle. He had suggested that ‘the remains of one of the numerous unknown men who fell and were buried in France should be exhumed, conveyed to England, cremated if necessary, and given an imposing military funeral in Westminster Abbey on November 11th’.

After a lengthy discussion, in which the Chief of the Imperial General Staff declared that the Army would be unanimously in favour of the proposal, the Cabinet agreed, and plans were swiftly put into motion to make sure that this plan would come to fruition (WORK 20/1/3).

Records held at The National Archives shed light into this last-minute planning, and how the interment of the Unknown Warrior would coincide with the unveiling of the new permanent Cenotaph in Whitehall. After overcoming objections that this type of event would be deemed as ‘sensational’, the view was taken that such a gesture would be acceptable to the people, honour fighting men, and do so ‘without singling out for such distinction any one known man’. Arrangements were made for the selection of the individual and plans put together for their transportation to London.

The ship chosen to take the coffin of the Unknown Warrior from Boulogne to Dover was HMS Verdun. The vessel was specially selected to perform this duty as a compliment to France, given the significance of the Battle of Verdun to the French people.

As late as 6 November, the Admiralty notified the Commanding Officer of the vessel that ‘Their Lordships have selected HM Ship under your command to convey a coffin containing the remains of an Unknown Warrior…on November 10th’. The letter went on to provide instructions as to how the coffin was to be treated:

‘The coffin is to be received on board HMS Verdun by a seaman guard of about 20 men under an officer, and placed on a bier [pedestal] in a suitable position. A large Union Jack is to be taken to cover the coffin from Boulogne to London. Colours to be half-masted as the coffin arrives on board. The ship’s company is to be fallen in. After arrival on board, sentries with arms reversed are to be posted round the bier’ (WO 32/3000).

Upon its arrival in Dover, the military garrison there was also given further instructions as to the procedure to be adopted. Once HMS Verdun had passed through the entrance of the Harbour, a 19-gun salute would be fired by No.11 Fire Command, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA).

The vessel was to come alongside No.3 berth, and was to be met by the band of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers, which would be playing ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. The coffin would then be conveyed to the railway carriage, bound for London Victoria Station, by six bearers, one man from each of: the Royal Navy; No.11 Fire Command, RGA; 2nd Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers; 2nd Battalion, Connaught Rangers; Royal Marines; and Royal Air Force. Guards of honour, consisting of 3 officers and 100 other ranks, from the two Irish regiments stationed at the Dover Garrison, as well as students from the Duke of York’s Royal Military School, would then line the route through the town. The band was to play a slow march while the coffin was carried to the railway platform (WO 32/3000).

The coffin was to be placed in a luggage van, the same van which had carried the bodies of Edith Cavell, a nurse executed in 1915 for helping Allied service personnel escape in occupied Belgium, and Captain Charles Fryatt, a Merchant Navy Captain who was executed in 1916, having attempted to ram a U-boat off the Netherlands coast in March 1915. It would arrive at Victoria Station by the afternoon of the 10th.

The event at Westminster Abbey was also to coincide with the unveiling of the permanent Cenotaph at Whitehall. A temporary memorial had initially been built, but the Cabinet had authorised Sir Edwin Lutyens to create an exact replica on the same site as the original at an estimated cost of £10,000, ‘in order that on the day of the Peace Procession the Nation should visibly express the great debt which it owes to those who, from all parts of the Empire irrespective of their religious creeds, had made the supreme sacrifice’ (WORK 20/139).

Though initially saying that he would not unveil the memorial (because of fear this would appear too ostentatious), following a groundswell of public feeling, the King agreed to perform the unveiling ceremony (WORK 20/1/3).

By 2 November, the Memorial Services Committee had decided that ‘the remains to be interred in the Abbey shall be those of an unknown British fighting man, and every precaution must be taken to ensure that his identity shall never become known’ (WORK 20/1/3). This broadened the initial proposals, when discussion had focused on the selection of, specifically, the bones of a soldier (they were not to be cremated – though this suggestion was in the Dean of Westminster’s initial proposal) who had fallen in 1914, and not just at any time in the war. This was even the preliminary recommendation made by the Cabinet, before the definition was subsequently broadened.

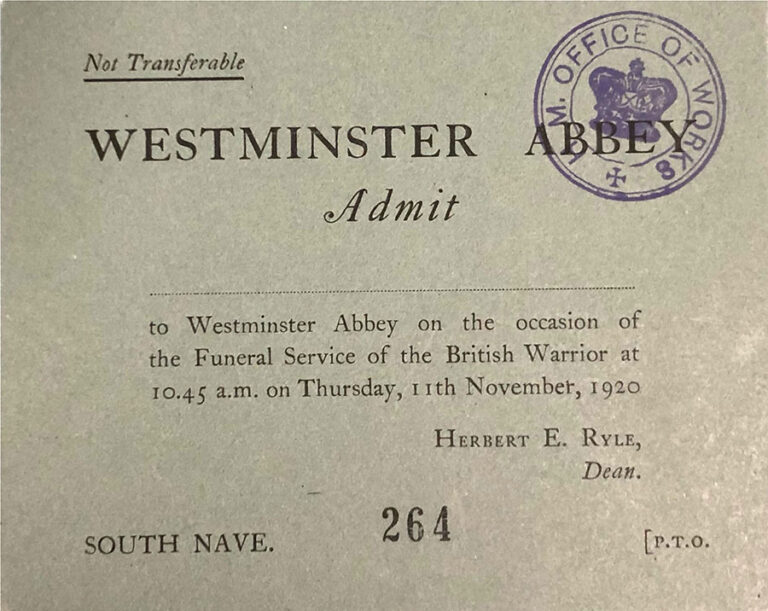

Tickets for the event at the Abbey were allocated by ballot. A team was responsible, in a period of only a few days, for dealing with callers and correspondence from ‘in all cases bereaved parents or widows who were labouring under deep emotion’, before allocating the tickets.

Applications exceeded 15,000, despite the short amount of time between the ballot opening and the event itself. Tickets were open to three categories of people: women who had lost a husband and one or more sons; mothers who had lost an only son or all sons; and widows. Nearly 100 applications were received from those who fell into the first category, and over 7,500 were received by mothers who had lost an only son or all or their sons (WORK 20/1/3).

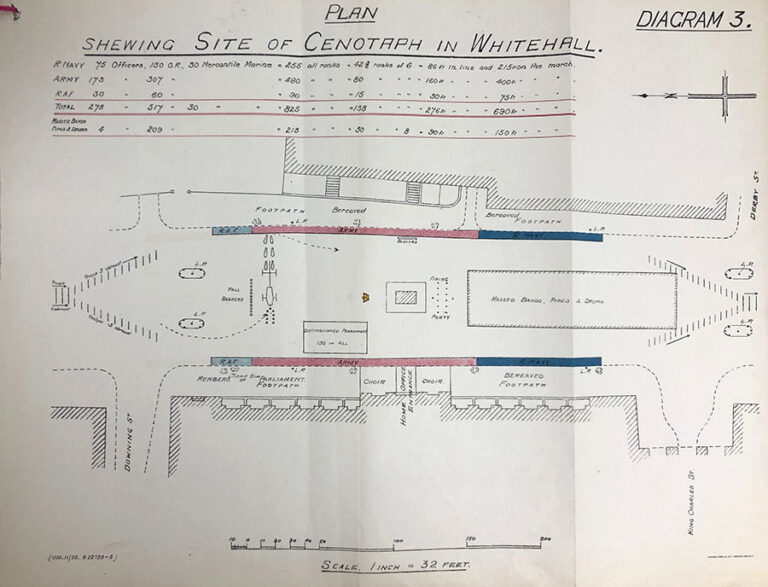

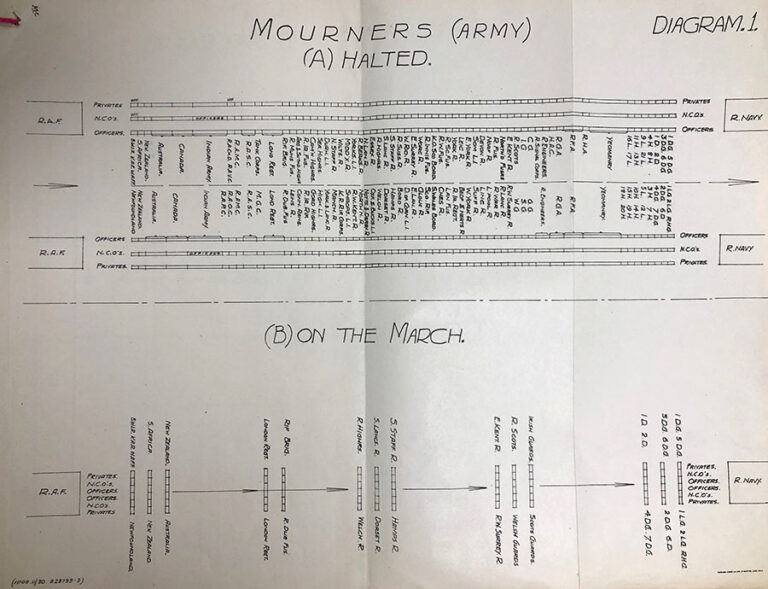

The event itself was carefully choreographed, as the funeral procession was to form at Victoria Station, taking a route through Grosvenor Gardens, Grosvenor Place, the Wellington Arch, Constitution Hill, The Mall, the Admiralty Arch, Charing Cross, and to the Cenotaph. Here they would be met by the King who would unveil the Cenotaph while Big Ben was striking the hour of 11.00. This would be followed by a two-minute silence, and a procession to Westminster Abbey, with the Coffin followed on foot by the King and his entourage. The former was keen to express that this would take place (and without the use of umbrellas) even if the weather was unfavourable.

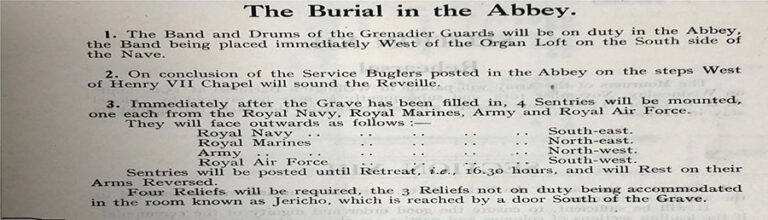

The troops detailed to process with the Coffin were the 3rd Battalion, Coldstream Guards. Members of the other Guards regiments of the British Army formed the band, and the mourners lining the route were to consist of 828 all ranks from the Royal Navy, Army, and Royal Air Force, in addition to 400 representatives of various ex-Service Men’s organisations, as well as 100 recipients of the Victoria Cross. Once at the Abbey the ceremony and burial was to commence (WO 32/3000).

On the day, everything went to plan broadly as had been outlined. Ex-service personnel, wives and widows were accommodated for, and the Coffin of the Unknown Warrior reached its destination. On its departure from Boulogne, Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the French former Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War, ‘entirely on his own initiative’ paid farewell to the coffin as it was embarked on HMS Verdun.

In the following year, in the lead up to Armistice Day, the United States presented the Unknown Warrior with the Medal of Honor, its highest award for valour, while the American Unknown Soldier (and by this time other nations had adopted a similar approach, most notably France and Belgium) was reciprocally awarded the Victoria Cross (WO 32/4996A).

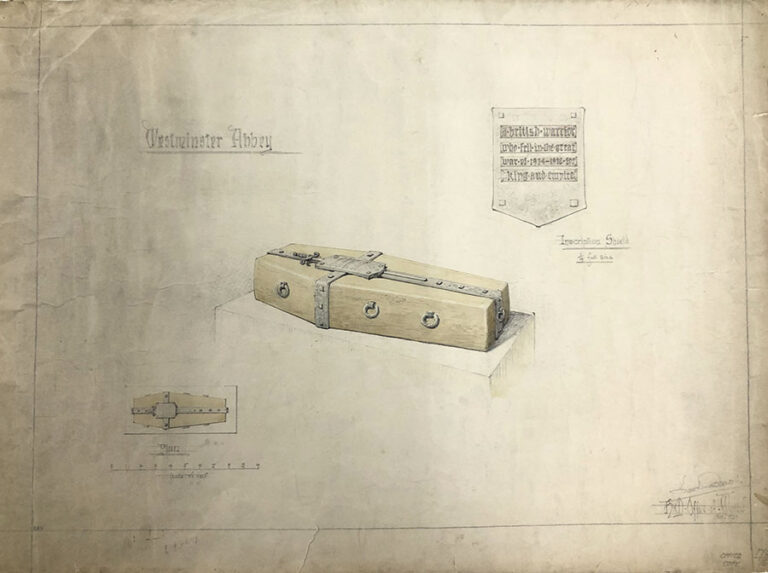

Eventually the tomb of British Unknown Warrior was to be capped with black Belgian marble stone, and remains the only tombstone in Westminster Abbey on which it is forbidden to walk.

A fascinating insight to the topic.

Wow, that description, supported by the documents, really felt like being there. God bless all who served, especially the ones represented by that unknown soldier.

Excellent research and presentation. Thank You

How extraordinary. How Poignant. Thank you.

No words,just Thank You.

I admire also how graves of unknown soldiers all over the world are maintained.

I found the article very thoughtful and precise I agree with the above comments form the people before me my grandfather fought in WW1 not as a soldier but as a medic, He and all others who fought that dreadful war were all damaged in some way and had no medical help at all, as we had not worked out that fighting men need care and compassion. I have stood in many military and civilian cemeteries around the world taking part in the Remembrance Service. One of the most moving in the centre of Jakarta where men of 80 plus years are buried beside 14 year old boys. It is called The Tea Planters Graveyard we were all handed crosses to put by a grave, slightly odd with the manic traffic noise in the background. We owe all the people that served our country a huge thank you all.

What an interesting article. Amazing attention to detail and makes one feel very British. Very well put together.

Thank you for this amazing insight into the history of the Unkown Soldier.

Really interesting. Thanks so much for this informative article.

The story of the ‘Unknown Warrior’ is a very moving story. I read some time ago that the train carrying the coffin was forced to slow down because of the thousands of people lining the tracks, I supose that all were thinking that the soldier could be of my family, in fact he could have been my great-uncle.

Very very interesting. I did not no any of the details. A wonderful gesture to bring a soldier to be laid to rest in the country he and many others went to fight for. R.I.P

Thank you so very much for the remembrance.

Readers of this very interesting post may like to know that Imperial War Museums has film of the Unknown Warrior journey onto HMS Verdun at Boulogne, the passage across the Channel, arriving at Dover and then part of the procession to Westminster Abbey. Also shown is the unveiling of the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

It’s available by simply going to https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060008261

Astonishing footage from one hundred years ago. What other treasures does the Imperial War Museum hold?

Having served 1939-45 RCAF as I am 103 (retired 1 month ago), I miss my comrades who never returned to Canada or have failed to last a century. I remember each one, recalling they volunteered to save our Mother Country and remove a mad-man.

A poignant glimpse of the past and a wonderful tribute to those lost.

An exceptionally well-written and interesting blog.

We will remember them.

We will remember them.

A very moving account of the steps leading to the tribute to the Fallen and very sobering to read about this in 2020.

Peter a brief answer to your question: many and varied!

Like ‘archives’ it has a bad rep from its name, leading to its real purpose – as a social history museum – being overshadowed by its collection of armament.

See images and the story of the dockworker and the rosebud from the Unknown Warrior’s wreath he picked up and sent to his nephew, telling the boy it was from his father’s wreath.

Go to https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30082803

a piece of history to be proud of and a lasting memorial for all those who have fallen without a gravestone or marker to remember them by

My maternal Grandfather, James Dunn, of the Coldstream Guards was part of those involved on the day, I believe he carried the Colours. He was one of the Old Contemptibles and had been awarded the Albert Medal (Bronze) for saving lives at several exploding ammunition railway trucks. In all, “Jimmy Dunn” saw 15 years’ service with the Coldstreams. He came from a very poor background in Clitheroe, Lancashire. His Mother had another son, Walter, discharged due to gassing and shell-shock, while her youngest (18 years), Freddy, was killed in action (with no known grave) just before the end of WW1. Family legend has it that Jimmy had tears rolling down his cheeks that day thinking of his young brother.

Sadly I never knew either of my Grandfathers, but I was privileged to march past the Cenotaph in 1918 as part of the special Centenary Commemorations.

(My other Grandfather Jack Nolan, a Police Sergeant, was the local “Aliens’ Registration Officer”).

Incidentally, the Albert Medal was known as the “Civilian’s VC”, and considered then second only to the Victoria Cross (he was a Member of the Victoria Cross and Albert Medal Association).

The Guards were only ever awarded 7 AMs, which medal later on was discontinued and replaced.

He was given a wartime military funeral in WW2, and was buried in the Guards’ Section in Brompton Cemetery, London.

Thank you for detailing this vast undertaking at such a time in our Nation’s history.

I am both proud and extremely pleased that we have this extremely poignant focal point for all to relate too.

A moving and wonderful insight into such an important part of our history. One can only imagine the emotion of that unique and special day. A lasting memorial for all our fallen. Never to be forgotten. RIP

I have read this, and comments, with eyes streaming.

Amazing how so much was planned and achieved so sensitively and quickly, for us to be able to honour the fallen in perpetuity.

Excellent article. Informative and very well written.

This event was also commemorated in three large canvases in oils by Frank O. Salisbury who was, to all intents and purposes, the Court Painter to the House of Windsor. His “The passing of the unknown warrior 11th November 1920” was exhibited at the Royal Academy and is currently in the UK Government Art Collection with a miniature in the Royal Collection. Also his “And they buried him among kings. Westminster Abbey 11th November 1920”. It was also exhibited at the Royal Academy and currently hangs in a committee room in the House of Lords. He captured the event in retrospect in 1924 with his large canvas of “India’s homage to the fallen”, in which four Indian officers pause at the Tomb prior to attending Princess Mary’s wedding at the Abbey in 1922. There are two slightly different versions of this; one at the Foreign & Commonwealth Office and the second at Sandhurst Royal Military Academy.

According to the Discovery catalogue the Metropolitan Police were unhappy about where the Cenotaph was sited (MEPO 2/1957: 1919: The Cenotaph: observations on Armistice Day services and unsuitability of Whitehall site). Was this just because it was in the middle of the road or is there another reason?.

Fascinating in truth. The process of selecting the body was carefully thought out and meticulously planned. The only shameful element was the early government resistance to the cenotaph project. It would have been a national disgrace had it had not been built.

John

Mon 9 Nov 20 at 19:44 hrs

Brilliant. Thank you very much.

Thanks to Richard above, this film was fascinating to watch, the transfer was dealt with in the utmost dignity and reverence.

Thank you, We will never forget them.

The photograph showing the cenotaph in November 1920 must in fact be the cenotaph of 1919, ie the temporary cenotaph. The wreath on the permanent cenotaph is carved in stone. The wreath in this image is a dark colour, quite possibly green but certainly not the stone of the permanent memorial.

Lovely to have so much detail about the planning and execution of the project. Thank you.

I believe that Sarah’s comment (10 November above) about the temporary Cenotaph is right.

Not only is the wreath not carved in stone, the supporting ribbons on each side are not carved either. Note also the real ribbon that has blown up onto the ledge supporting the wreath with its tail on the left of the photo.

In addition the flags staffs shown in the photograph above are angled outwards and not parallel to the sides of the memorial as they appear in the one unvieled in 1920.

That is amazing I always wanted to know more now my curiosity is fulfilled so moving and patriotic

I am 83 years , but I never knew of this ! Thank you! It has touched me greatly !

Very moving ceremony this morning and reading the history of the the ‘unknown soldier’. As a youngster my parents took the family to London following the queens coronation and I remember we Westminster Abbey. It didn’t mean a lot then but now, I am full of admiration and respect for those involved in the idea, execution and above all, keeping secret the identity of the soldier. I understand the one person who knew, took it to his grave. I do wonder however if it was being planned today, this secret wouldn’t have remained a secret, someone would have ‘leaked’ it for a price. Sad indictment and today’s generation.

The unknown soldier arrived at Victoria station platform 8 and spent the night there till he was taken to Westminster abbey the next morning.There is a memorial there and they have a ceremony every year on the 10th of November.

Amazing insight- I’ve always wondered. Thank you

I found the idea and the description compelling and I find myself asking who was The Unknown Soldier. I also feel a great sadness because I see both the unifying aspect and the cynical exploitation of an event by politicians hiding their role and lies that contributed both to the so called war to end all wars- which was nonsense and the carnage, death and suffering that came from it all. Unless we can all at last learn the lessons of history and stop fawning and following the kind of people who cause this mayhem that there will be a reckoning to come!

Just to add a little more… the luggage van used to transport the body of the Unknown Warrior from Dover to Victoria station in London was also used to carry those of Edith Cavell and Captain Charles Fryatt, both of whom were executed in Belgium during the First World War.

The van was restored some time ago and is (I believe) preserved at the Kent and East Sussex Railway centre.

Fascinating piece of history that I never knew. In tracing my family tree I have so far found four deaths. Three are buried in France in different cemeteries, the fourth missing. Thank you for informing us of the process. We shall never forget.

Richard (12 Nov 2020) is quite right about the wagon used (no 132) being on the Kent and East Sussex Railway. It’s at an intermediate station, Northiam, midway between Tenterden and Bodium, and can also be visited by car.

The wagon is beautifully maintained and has a replica of the coffin used for the Unknown Warrior, as well as explanatory boards on the walls to either side.

Thank you Pat for not only confirming my suspicions but adding detail.

As can be seen from the comments here, this post has attracted a lot of interest – not least from me!

I have been searching online for something I first saw a number of years ago on and couldn’t find until very late last night and is linked to the image of the Cenotaph above which Sarah suggested was of the original structure prior to the Portland stone version being unvielled.

The Imperial War Museum as was – now Imperial War Museums or IWM – had the top section of the p(wood and plaster) Cenotaph in its collection for a number of years, first at its South Kensington location and then at what is now IWM London, the familiar building with the naval guns outside in Lambeth.

The structure appears to have been destroyed when a German bomb hit the museum during the Second World War. This may have been in a raid that destroyed or damaged a number of First World War related artefacts on 31 January 1941.

IWM War Memorials Register has various photographs of this item in situ in the museum as well as sketches for alternative designs which included an Eternal flame.

Go to https://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/66225 and scroll through the fifteen images for more information on some of the designs and a number of pictures of the original Cenotaph top section.

Extremely informative and interesting. The addition information contained in various web sites is also very interesting. Thank you for all who contributed to this article. We shall remember them.