This is the second of our blog posts this week to mark the release of Mike Leigh’s film ‘Peterloo’. The production’s historian, Dr Jacqueline Riding, explains how the cast and crew utilised records from The National Archives while developing the film, and how archival research has allowed her to shine new light on just why the event became known as Peterloo. Read our first blog post on the history behind the film.

Cover of Jacqueline Riding’s new book ‘Peterloo’.

I had been the historical and art historical consultant on Mike Leigh’s ‘Mr. Turner’ (UK release 2014) and, after a short break, returned to Thin Man Films as the historian on ‘Peterloo’. We started with the basics – books and articles on the Peterloo Massacre itself, broadening out to cover areas of social and political history.

Very early on, Mike and I made a research trip to Manchester – visiting Chetham’s Library, Manchester Central Library, the People’s History Museum, the Working Class Movement Library and Touchstones Museum in Rochdale. We also met with Professor John Belchem, biographer of Henry Hunt, and Peterloo expert Dr Robert Poole, with whom we walked the site of the massacre. Formerly known as St Peter’s Field, it is contained within the Peter Street, Windmill Street and Mount Street ‘triangle’ where now stand the Midland and Radisson Hotels (the latter originally the Free Trade Hall).

Once core casting had occurred, and during the six-months rehearsal period from November 2016 to April 2017, I and the rehearsal team organised further research visits.

At the same time, the production team and the actors, within their separated groups – whether ‘magistrates’, ‘reformers/radicals’, ‘Home Office officials and staff’ or ‘journalists’ – made several visits to The National Archives in Kew. Of prime interest were the Home Office papers HO 40 (Disturbances Correspondence) 41 (Disturbances Entry Books, copies of outgoing letters), 42 (Domestic Correspondence, George III) and 79 (Private and Secret Entry Books). Many of these records are available online.

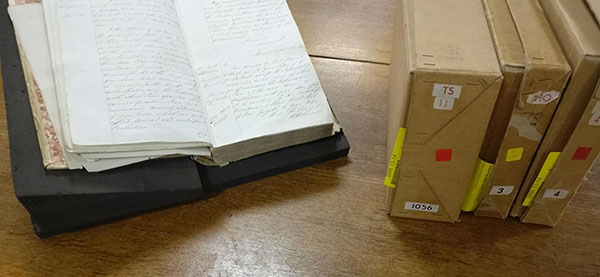

A selection of some the documents consulted by the crew at The National Archives. Alt text: A selection of some the documents consulted by the crew at The National Archives, pictured are HO 79/4 (open volume), TS 11/1056, HO 79/3 and HO 41/4

Records specialists Paul Carter and Chris Day from The National Archives kindly arranged for a large selection of records to be available for us to consult and, with Katrina Navickas and Nathan Bend of the University of Hertfordshire also on hand, explained the type of documents held by the archives and how to view them – either online, or in the reading rooms. Nathan’s doctoral thesis (Paul and Katrina were his supervisors) focused on the Home Office and Public Disturbance c 1800-1832, and his intimate knowledge of the documents proved fascinating and enlightening. His work on how the Home Office functioned fed into the design and props of the Home Office set and the sense of organised chaos within the scenes.

The visits to The National Archives – in groups and then individually – were invaluable for the actors’ independent research, feeding into the development of their characters and, later, the onset improvisations, from which each scene (dialogue and action) would gradually emerge.

I returned to the archives after filming was completed in September 2017, to start specific research for my tie-in book, ‘Peterloo: The Story of the Manchester Massacre’ (Head of Zeus, October 2018). Aside from revisiting the Home Office papers, from which I have quoted extensively, I also needed to consult documents associated with another event – four years before Peterloo – from which this ironic name sprang.

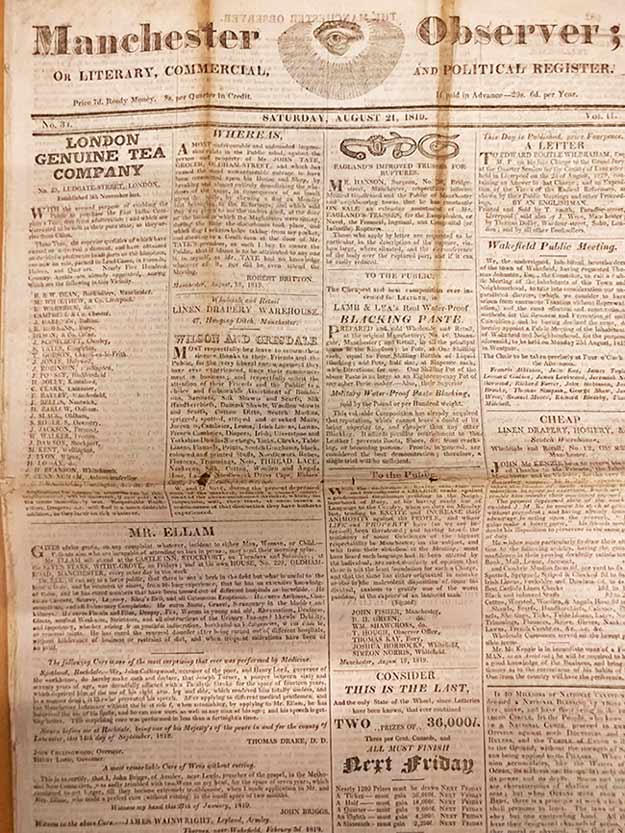

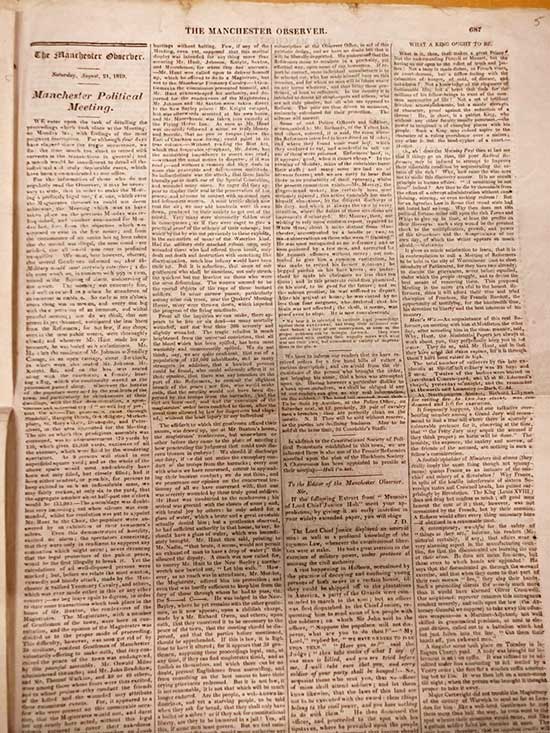

The front cover of the Manchester Observer, owned by Joseph Johnson (arrested at Peterloo) from 21 August 1819, just after the Massacre took place. Catalogue reference: HO 42/192

One of the key individuals connected to Peterloo was not a magistrate, nor a parliamentarian, but a young cotton-factory worker called John Lees of the Parish of Oldham, Lancashire. John was one of the tens of thousands of people drawn to St Peter’s Field, Manchester on 16 August 1819. They came to hear Henry Hunt demand, in stirring terms, the fundamental reform of the electoral system to embrace universal male suffrage: one man, one vote. A few hours later, John left the field severely battered, cut and bruised, like hundreds of others. But unlike most of the victims from that terrible day, John died three weeks later from horrific internal injuries. The coroner’s inquest that immediately followed – in the wake of wide-spread disgust at the brutal treatment meted out to John and his fellows – turned this single victim into a cause célèbre. The inquest focused efforts to bring those responsible to justice, whether magistrates, cavalrymen or special constables.

Yet, given the importance of the inquest, little is known about John Lees himself. During research to uncover information for my book – specifically to confirm the crucial, oft-quoted detail that he was a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo (18 June 1815) – more complications arose than I had expected. [ref]See Jacqueline Riding, ‘Peterloo’, 2018, p.1, pp.341-42[/ref]

The starting point is the eye-witness account, recorded in the published inquest transcription, of William Harrison: a cotton spinner who was present at St Peter’s Field and then visited John Lees five days before the latter died. During this meeting, William recalled, John declared:

He was at the battle of Waterloo, but he never was in such danger there as he was at the meeting: for at Waterloo there was man to man, but at Manchester it was downright murder. [ref]The inquest transcription was published in 1820. An electronic copy can be found on the fantastic Peterloo Witness Project’s website. This quote appears on page 73.[/ref]

No further details of John’s military career are given in this source. John’s father, Robert, who did not challenge William Harrison’s claim, confirmed that his son was 22 years old when he died on 7 September 1819.

In his book on the veterans of Waterloo, ‘The Scum of the Earth’ (2015), Colin Brown quoted from a document he had consulted at The National Archives concerning John Lee’s enlistment into the British army. [ref]Colin Brown, ‘The Scum of the Earth: What Happened to the Real British Heroes of Waterloo?’, The History Press, 2015, pp.169-70[/ref] As there was no reference or footnote, I contacted Chris Day asking what this document might be. Chris directed me to the War Office papers; he pointed out that, from his initial search, there appeared to be two men called John Lees of Oldham who may correspond to the victim of Peterloo.

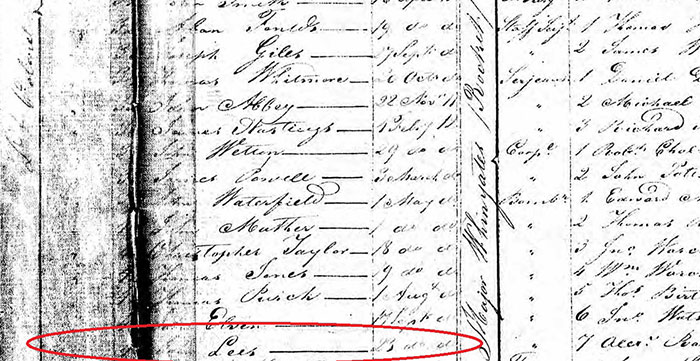

Driver John Lees’ very faint (circled in red) entry in the Waterloo Medal Roll. Catalogue reference: WO 100/14

Lees is a popular name in this part of Lancashire, while John is certainly one of the most popular first names in England, now as then. In fact further archival digging revealed not two, but three ‘John Lees’, all born in the Parish of Oldham, listed in the War Office Campaign Medal and Award Rolls (General Series): Waterloo WO 100/14 (1816). The first is listed under ‘private’ in the ‘1st Regiment of Life Guards’ and recorded as ‘wounded’ in the battle (f.10). The second is listed as number ‘45’ under ‘drivers’ in Major Robert Bull’s Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) ‘I’ Troop (f.202r); and the third is listed as number ‘72’ under ‘gunners’, also, amazingly, in Major Bull’s RHA ‘I’ troop (f.202v). Two John Lees of Oldham, not just in the same regiment but the same troop. But which John Lees was at Peterloo?

The first from the Life Guards can be discounted as he was discharged aged 23 in 1816 (WO 97/187/64).

Of the two John Lees serving in Major Bull’s RHA ‘I’ troop by 1816, the documentation states that the driver enlisted on 23 September 1812 (WO 100/14 f.202v); the gunner enlisted in the same year but on 22 July (WO 100/14 f.202r). Further information is provided in WO 69/2, Description Book of the Non Commissioned Officers, & Privates of the Royal Horse Artillery. Here the driver is described as ‘no.14’, a ‘Cotton Spinner’, aged 14 years when he enlisted at Manchester on 23 September 1812, 5 feet 4 ¼ inches in height, with a ‘fresh’ complexion, ‘brown’ hair and ‘grey’ eyes (WO 69/2/2345).

The gunner ‘no.5’ is also, unhelpfully, described as of a fresh complexion with brown hair and grey eyes (f.158v), but aged 18 years, 5 feet 6 ½ inches in height and as enlisting at Rochdale on 22 July 1812 (WO 69/2/2351, f.158v). This John Lees was a ‘weaver’ and assigned to 6th Battalion, 6th Brigade, ‘I’ troop (f.159r) while John Lees the driver was assigned to ‘RADrs’ (presumably Royal Artillery Drivers) ‘B’ troop. Another source, WO 69/4, Description of Men in Great Britain (L/2310) offers similar details for both men, with the additional information that the driver (ff.141v–142r) was ‘inlisted’ [sic] by ‘S Wilson’, first mustered in the ‘7th’ battalion and transferred to the RHA in May 1813 (for the gunner’s entry see ff.142v–43r).

We also know, from the list of the recipients of the Waterloo medal (WO 100/14 ff.235-236, f.236r and f.236v) that Major Bull’s I troop formed part of the army of occupation post-Waterloo, as their medals were sent to Cambrai where they were stationed.

Having traced the two men to this point, I was happy to conclude that John Lees the gunner was not the man who died in 1819, as he would have been around 25 years old in that year (based on his given age, 18, in 1812). Also, via further sources, he appears to have been discharged in 1835 aged 40 (WO 69/7/161 and WO 97/1243/56). In another source his discharge date is listed as 1836 and his age given as 41 (WO 97/1243/55).

Article on the Peterloo Massacre published by the Manchester Observer, 21 August 1819. Catalogue reference: HO 42/192

Which leaves us with John Lees the RHA driver. Further delving might produce more information to support the following, but this John Lees’ recorded age on enlisting (aged 14 in 1812) at least tallies with the age at death of the Peterloo victim. Based on this evidence, I felt confident that it was John Lees the Royal Horse Artillery driver who died of the wounds he received on St Peter’s Field.

John Lees does not appear in the film, but he is there in spirit in the invented character Joseph Ogden. However, by using The National Archives records we now have a better sense of the young man who is so central to our understanding of this momentous event in British History.

Really interesting to see how much research went in to the film.