Opening Up Archives, now in its second year, is a collaborative project supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, The National Archives, and a number of host organisations across the country. You’ll be hearing from most of the 13 trainees in the coming months as we share our thoughts about what we’ve learned working and training within the sector.

Part of my role here as a trainee at Nottinghamshire Archives is to investigate how digital media can be used to bring the public closer to some of the archival collections we care for, and Nottinghamshire’s history more broadly. To that end, I’ve been tweeting as a frustrated 18th century spinster, developing an online presence for a youth heritage conference, and coding away at things which I hope to share very soon. I’ve also been learning a bit about the importance of digital preservation, but there are more knowledgeable people around here who can tell you about that.

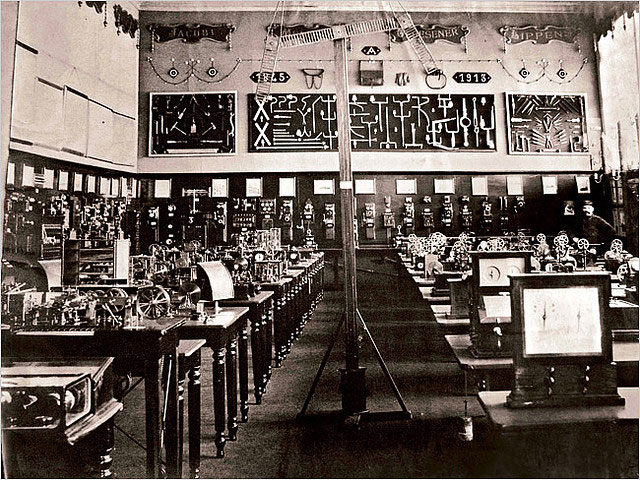

Mundaneum, early web concept – CC Matthew Burpee – http://www.flickr.com/photos/mburpee/2589663547/

Working at the intersection of old records and new technologies, I’ve been thinking a lot in recent months about how digital culture is changing the world of archives, and I was surprised to learn that these changes aren’t entirely unanticipated. In 1910 Paul Otlet, a man described as ‘one of technology’s lost pioneers’, envisioned a ‘city of knowledge’ that the Belgian government soon offered him funding to build in a wing of the Palais du Cinquantenaire, which he eventually named the Mundaneum (there’s a museum dedicated to it today in Mons). Otlet and his friend, the Nobel Prize winner Henri La Fontaine, used the Universal Decimal Classification that they had already invented to sort and store some 12 million index cards and documents at the Mundaneum, although this vast quantity of material called for an increasingly large number of workers to curate it.

Otlet had also been working with an engineer to store bibliographic data on new media, and by the late 1920s the pair had managed to store an entire encyclopaedia on microfilm. Otlet’s experiments with emerging technologies didn’t end there though: in seeking to provide universal access to his paper database, he had a telegraph room installed at the Mundaneum through which anyone in the world could submit a query, hoping that by doing so ‘anyone in his armchair would be able to contemplate the whole of creation.’ The project was doomed though – the Belgian government, having lost interest in the project, ceased funding Otlet in 1934. He stood in protest for a while outside the locked archives, but they remained untouched until the Nazis invaded six years later and either destroyed or removed the collections.

It’s not surprising that the Mundaneum has been likened to ‘snail-mail Google and a card-catalogue Web’, a comparison that suggests current changes in the archival world are progressions as opposed to disruptions. It’s important, I think, to note these continuities in order to understand the depth of the challenges and range of opportunities present in the digital age. On the one hand, Paul Otlet’s work demonstrates that what seems revolutionary is in fact the realisation of a much older vision, but on the other hand there are clear changes in both the working practices of archives and the availability of the materials they house, and as the nature of that material becomes increasingly born-digital they are faced with new challenges that not even Otlet could have imagined.

In my own way, I’m trying to understand those challenges here at Nottinghamshire Archives, and I hope that the skills I bring can help to broaden access to the county’s past. I might not match Otlet’s ambition in that respect, but I hope at least that I’m remaining faithful to his aims.

I’ve heard of this Mundaneum before – seems like a fascinating concept. An interesting blog post, thanks!