‘How are we going to pay tax? We depend upon our husbands, we cannot buy food or cloth ourselves: how shall we get money to pay tax?’

These were the words of Uloigbo, a Nigerian woman from Oloko, explaining how women in the south-east of the country began a series of protests in 1929. These protests became known as Ogu Umunwanyi or Ekong Iban in the Igbo and Ibibio languages; or Women’s War in English.

It was estimated that the resulting protests included tens of thousands of women. The scale of these demonstrations and the resulting violence unnerved the British colonial government who eventually produced a lengthy report, ‘the Aba Commission of Inquiry’, a copy of which is held in here at the National Archives in the UK (catalogue ref: CO 583/176/8).

The report offers a very partial account of that protest, framed by colonial understandings of Nigerian society, and a male perspective on gender relations. Nonetheless, it still documents that history, including eye-witness statements of those involved, and naming those who were injured or killed in the protests. In this blog, for Women’s History Month, we will explore how our records describe what led to the protests, what happened, and what they tell us about women and their position in colonial Nigeria.

Colonial administration in Nigeria

Traditionally, women had played an important role in many Nigerian societies. They were involved in political decision-making and their domestic and commercial work had value and status in their communities. Under British colonial rule, the ability of women to participate in and influence society had been reduced, and their contributions disregarded.

A system of ‘indirect rule’ had been implemented by the first governor of Nigeria, Lord Lugard. This involved using the pre-existing traditional structures of authority to govern the population, but under the overall control of the colonial powers.

In south-east Nigeria, the colonial administration ran a system of ‘Native Courts’ to hear cases that were resolved through traditional law. The courts were headed by Warrant Chiefs that the colonial administration appointed from the Igbo population, along with court scribes and messengers. However, the Warrant Chiefs in particular became a focus of resentment as they abused their power, imposing unfair regulations and imprisoning critics.

Introduction of direct taxation

The British government had introduced direct taxation in regions of Nigeria where it was customary to pay tributes and tolls. But this had not been usual practice in the south-east. However, in April 1927, the colonial government began preparing to extend direct taxation into south-eastern provinces through the enforcement of the Native Revenue (Amendment) Ordinance.

The purpose of the tax was explained to communities, and a list of male ‘heads’ of households was compiled. Despite protests and disturbances in the Warri (now Delta) Province (see footnote 1), the tax was introduced in April 1928. Then in September 1929, an assistant District Officer, Captain J Cook, decided to gather additional information about the area under his administration.

Cook sent enumerators to count women, children and livestock in each household, but this was interpreted as a precursor to a direct tax on women themselves. Traditionally women supported families and helped to pay men’s taxes, but they were not taxed directly on their own account. Under the new colonial order, their opportunity to influence decision-making had been reduced, so it’s no surprise women questioned why they should now pay tax.

Sparks of protest

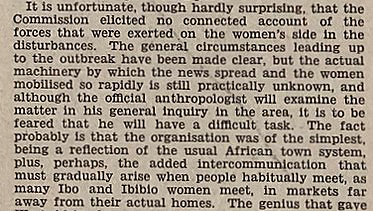

The sparks of protest against the perceived tax on women began in the town of Oloko, Bende Division, when a woman, Nwanyeruwa, refused to co-operate. The colonial report describes some ambiguity around the events that caused the protest, however it seems that the enumerator, Mark Emeruwa, argued with Nwanyeruwa and grabbed her by the throat.

![Typed extract from a report. Part of it says: he says [Emeruwa] that he found Ojim himself there and upon his explaining his errand Ojim vouchsafed no reply, but told his women that Emeruwa had come to do the counting.... Nwanyeruwa's story is that Emeruwa came to her house whilst she was squeezing oil and asked her to count her goats, sheep and people. She replied angrily... Thereupon Emeruwa seized her by the throat...](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/29085458/Nwanyeruwa-and-Emeruwa-768x380.jpg)

Word of the incident spread, and on 29 November 1929, 10,000 women gathered to protest at the home of Okugo, the Warrant Chief for the town of Oloko. The women employed a technique known as ‘sitting on’ the Warrant Chief – singing and dancing around his house for a number of days and nights (see footnote 2).

On 28 November, Captain J Cook arrested the Warrant Chief for assault on some of the women and ‘threw Okugo’s cap of office to the mob’ (see footnote 3). On 4 December, Okugo was tried and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment ‘on charges of spreading news likely to create alarm’ (see footnote 4).

In the following days protests spread across the province, led by women and sometimes including men. Court buildings were attacked, and prisoners released, symbolising a rejection of the structures of colonial rule. The protesters also targeted palm oil stores and livestock belonging to Warrant Chiefs, effectively withdrawing their economic contributions to the colonial-sanctioned administration.

On a number of occasions, shots were fired at protestors; sometimes overhead, sometimes at their feet, but also directly into the crowd.

Incidents with fatalities included the following:

- 11 December – as women were obstructing and attacking the cars of private traders, two were knocked down by Doctor Hunter, a British doctor driving to the hospital. Both women later died.

- 15 December – 16 women were killed as they attacked a military camp in Utu Etim Ekpo. A further ‘mob’ was dispersed with fire, killing two and wounding seven.

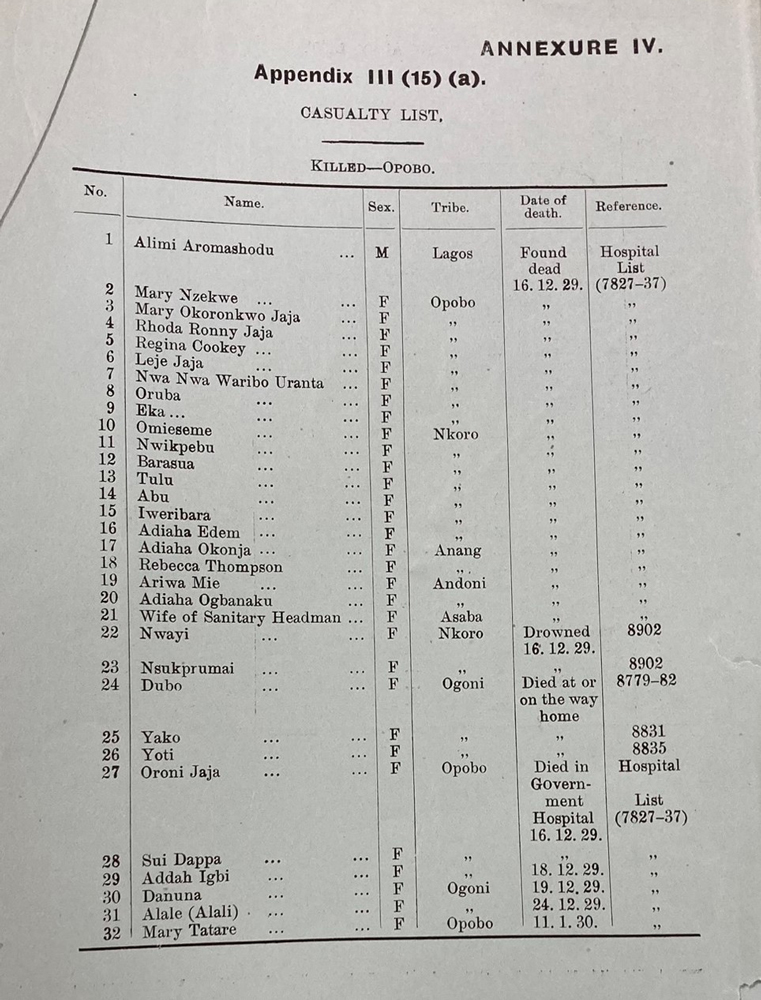

- 16 December – women gathered at Opobo town and when the crowd ‘became hostile’ 62 shots were fired. 31 women and one man were killed, and 31 women were wounded.

Commission of Inquiry report

The Aba Commission of Inquiry interviewed hundreds of witnesses, including indigenous men and women, court officials and colonial administrators.

The first-hand accounts in the report are fascinating. The relative power of the colonial authorities compiling the report and the witnesses who were called to testify make it difficult to read the statements as the ‘authentic’ voices of those involved. The testimonies of non-English speaking witnesses in the report also went through ‘several linguistic filters which ricocheted from interpreters whose first language was not English but were tasked with its interpretation into vernacular and from vernacular into English’ (see footnote 5). Historian Ngozi Edeagu describes moments in the report where the richness of local languages added even more layers of translation or loss of meaning. She points to the testimony of Emmanuel Nwumba Inyama who reported that he couldn’t tell the Commission what he heard the women singing, because he didn’t share their dialect (see footnote 6). This means that the possibility of linguistic misinterpretations needs to be considered when reading the testimonies.

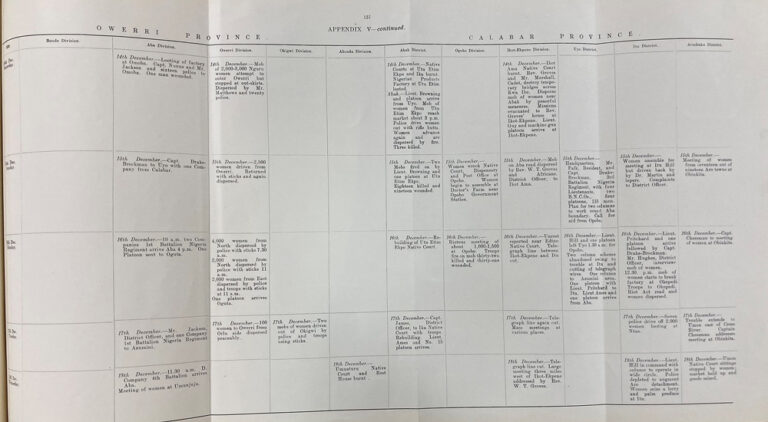

What the report communicates very clearly, however, is the scale of the event and the difficulty the colonial authorities had in understanding what had taken place. Appendix V of the report consists of a number of fold-out pages that show the numerous incidents that occurred across the different divisions of Owerri and Calabar provinces in November and December. The pages look something like a modern-day spreadsheet, with dates down the left-hand side and the various administrative divisions across the top. It’s clear from these pages that the geographical extent of the unrest and the way different events were responded to was difficult to put across in the main body of the report.

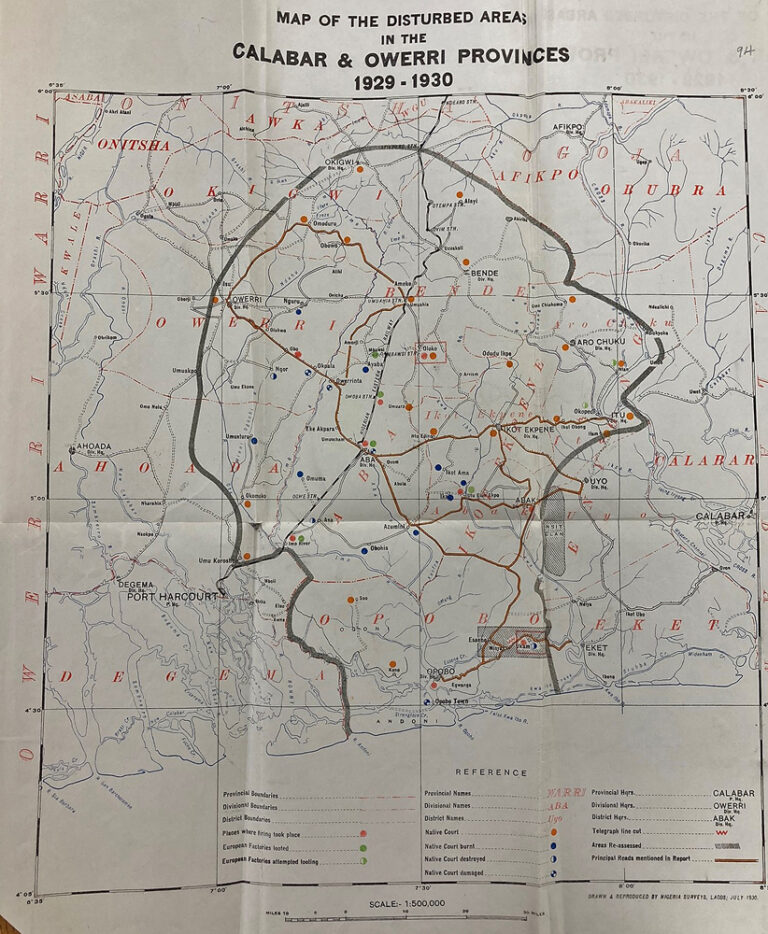

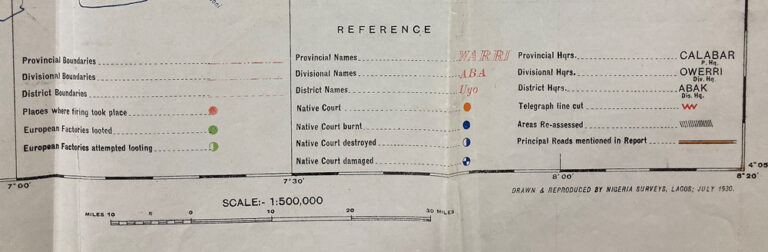

At the end of appendix V is a map, showing provincial, divisional and district boundaries; places where firing took place, factories that were looted, native courts that were damaged (to varying degrees) and telegraph lines that were cut.

Almost all the casualties of the protests were women. The most striking Appendix to the report contains lists of the women that were killed and wounded. Seeing the names, tribes, towns, and other details of these women is very powerful. We decided to include the full list of those killed at Opobo as a mark of remembrance. Although it is undoubtedly sad to see the women, and one man, made real by their naming, it is significant that this information has been preserved when we might not have expected to be able to find it.

Women as political agitators

The report shows some confusion amongst the British colonial administration about the fact that women were able to organise such a powerful protest so quickly. One of the key questions of the enquiry was that of ‘the origin of the organisations which enabled them to collect together in such vast numbers in so short a time, and their leaders to exercise such discipline and control’ (see footnote 7). The Colonial Secretary of State for the Colonies stated that ‘disturbances in which women have taken the foremost, or the only, part are unknown here and elsewhere in the Empire’ (see footnote 8).

This doesn’t, however, appear to be the case. The report itself describes several instances of women’s mass demonstrations in the Calabar and Owerri Provinces in the 1920s. One of these had been to lobby for a return to traditional customs, another to advocate for Christian revivalism. A third described in the report as a ‘political movement pure and simple’ had been a refusal to pay tolls on market stalls, in which a demonstration by women was followed by a boycott on selling food to white colonial residents (see footnote 9). However, the lack of colonial understanding of Nigerian society in general, and women’s social and cultural practices in particular, meant that this political organisation had been discounted or made ‘invisible’ (see footnote 10).

The report also catalogues some mechanisms through which the women conducted their protests. These included sending palm leaves as a signal for help, collective dancing and singing as a way of exercising influence over individuals who had wronged women, and the discussion and planning in traditional ‘women’s meetings’. One colonial officer describes these meetings as the manifestation of an ‘organised sisterhood’ (see footnote 11). When the newspaper West Africa published its reaction to the report, however, it noted that the Commission had failed to identify the methods used by the women to spread word of the protests. Many aspects of women’s lives had remained ‘invisible’ even after the Commission had set out to explain them.

Aftermath

Once the colonial authorities succeeded in suppressing the protests, they implemented numerous collective punishments (see footnote 12). This was a common practice of colonial administration, in which huts were burned and the property of whole communities destroyed. Nonetheless, the Aba Commission’s report also produced a number of recommendations around taxation and the native court system, some of which were positive changes for the communities involved. Among them were recommendations that:

- The system of assessing the number of male adults using a factor deduced from the ratio of houses to men should be abandoned.

- Any attempts to introduce ‘lump sum assessment’ should be done slowly and only with the willing cooperation of the chiefs and people.

- A Commission should be appointed to enquire into the Native Court system.

- Native Court members should be chosen by the people at a town meeting and should be appointed for a fixed term rather than for life.

- A free pardon should be given to Warrant Chief Okugo and Mark Emeruwa who were both involved in the earliest incident with Nwanyeruwa.

Despite mixed results, the women’s action did improve their position in society with some replacing Warrant Chiefs and serving on native courts and the events of 1929 are seen as inspiration for later protests (see footnote 13).

The colonial authorities report that the women in the Women’s War called themselves ‘Oha Ndi Nyiom,’ translated as ‘women’s world’ or ‘the spirit of womanhood’. For the authors of the report there was a parallel to the action between the actions of the women in Women’s War, and the ‘militant feminism’ of the suffragettes in England (see footnote 14). While the contexts were vastly different, what we do see in both is women sharing, collaborating and taking risks to secure their rights in society. To mark the close of Women’s History Month, we salute you.

Footnotes

- The Anti Tax Riots in Warri Province, 1927-1928 by Obaro Ikime. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria Vol 3 No 3 (December 1966) pp 559-573. Accessed 23 February 2023

- Wikipedia – the Women’s War. Accessed 23 February 2023

- CO 583/176/7: Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: Summary of Aba Commission of enquiry report

- ibid

- Critiquing witness testimonies in African colonial history: A study of the Women’s War of 1929 by Ngozi Edeagu. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria Vol 26 (2017) p49. Accessed 23 February 2023

- ibid p53

- CO 583/176/8 p18 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: correspondence arising from Aba Commission report 1931–32

- Critiquing witness testimonies in African colonial history: A study of the Women’s War of 1929 by Ngozi Edeagu. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria Vol 26 (2017) p44. Accessed 23 February 2023

- CO 583/176/8p18 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: correspondence arising from Aba Commission report 1931–32

- ‘Sitting on a Man’: Colonialism and the Lost Political Institutions of Igbo Women by Judith van Allen. Canadian Journal of African Studies Vol 6 (1972) p165-181. Accessed 6 March 2023.

- CO 583/176/8 Appendix p4 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: correspondence arising from Aba Commission report 1931–32

- Wikipedia – the Women’s War. Accessed 23 February 2023

- ibid

- CO 583/176/8 p20 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: correspondence arising from Aba Commission report 1931–32

Document references

- CO 583/176/7 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: Summary of Aba Commission of enquiry report

- CO 583/176/8 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: Aba Commission report

- CO 583/176/9 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: correspondence arising from Aba Commission report 1930

- CO 583/176/10 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces Dec 1929: press coverage

- CO 583/177/11 Native unrest in Calabar and Owerri Provinces, Dec 1929: correspondence arising from Aba Commission report 1931–32