In the aftermath of the Anglo-Irish War (1919-21) the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) force was disbanded as part of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. There followed a compensation scheme for ex-RIC members to claim hardship funds and commutation of pension. By the mid-1920s an Irish Grants Committee was also set up to award hardship payments for those who had stayed loyal to the British government during the war.

A changing role

For generations the RIC had recruited young Irishmen to its force as the ‘eyes and ears’ of the state and had achieved substantial acceptance in Irish communities. Local constables developed an unrivalled local knowledge that, during the conflict, became a direct threat to local Sinn Fein clubs and volunteer bodies. Hence the latter mounted a campaign of ostracism and violence against the RIC.

Even before the conflict began in January 1919, aggressive actions against nationalist activity by armed RIC men contributed to a more violent environment. DORA (Defence of the Realm Act) empowered the police to search for arms, arrest suspects and break up meetings. Founded as a rural police force, the RIC now confronted political organisations like Sinn Fein through emergency regulations and military-style tactics. Moreover, it was increasingly reliant on military assistance.

RIC monthly reports, particularly after 1918, narrate a self-inflicted community relations wound by too close an association with the military. By December 1919 the Inspector General of the RIC reported that:

‘many of the more isolated police barracks have had to be closed in order to augment the force in the remainder for defensive purposes and to enable patrols to be strengthened … It has caused apprehension among law-abiding citizens in the localities affected, who feel they are left without adequate protection.’

RIC Monthly Report, 15 December 1919, CO 904/110 P475

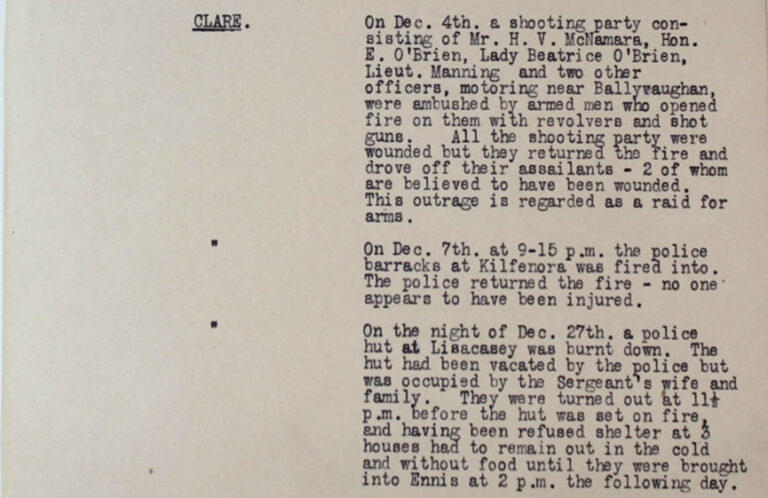

Inspector General Byrne also acknowledged a ‘spirit of lawlessness’ and that the police were not strong enough to cope without military assistance. A growing estrangement was occurring between the police and their communities. One incident foreshadowed what was to become a feature of the war. It was thought safe to allow police families to occupy vacated stations. However, in December 1919 a sergeant’s family was turned out of a vacated hut at Liscasey, Co. Clare. The hut was burned and the family refused shelter in any of the neighbouring households (see RIC Monthly reports, 13 January 1920, CO 904/110). Boycotting and ostracism became commonplace.

On disbandment in April 1922, the RIC still had some 8,000 Irish-born members. These included both ‘old RIC’ men who joined before the War of Independence, and ‘Black and Tans’ recruited after 1920. The latter were mainly English-born ex-servicemen, recruited to meet the shortfall from resignations within the force during the conflict. Most were Catholic and were forced to leave the new Free-State either temporarily or permanently. Even after the conflict formally ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, several ex-RIC were killed in 1922.

Consequences of war

In April 1922 RIC Deputy Inspector General C A Walsh advised that ‘the vast majority of both officers and men enlisted in Ireland will not be allowed on disbandment to remain … They will be compelled to leave the country and it is anticipated that most of them will remove to Great Britain’ (see HO 351/98, Walsh to Assistant Under Secretary, RIC Tribunal). One observer commented that the men were ‘worn with anxiety’ (see P A Marrinan, RIC County Inspector to Lord Middleton, 26 March 1922, PRO 30/67/49). In reality though, the experiences of disbanded policemen varied significantly. Many settled without disruption. Some remained in Ireland despite threats and boycotting, while others were either pressured to leave or went of their own free will. In December 1922, the Daily Mail reported on a ‘little colony’ of ex-RIC families in Letchworth, Hertfordshire:

‘The men are living primarily on their pensions … but they are all anxious to find posts in this country … and these splendid men, remarkable for their physique and intelligence, are being wasted. Their wives are delighted with the picturesque, well-built houses found for them … The women are very brave. The horrors and fears of the last five years are seen in their haunted eyes, but they seek to forget their sufferings in the pride of their pretty homes. The children, with the adaptability of youth, are already perfectly at home.’

Daily Mail, 11 December 1922

Some experiences are recorded in the RIC Tribunal files, founded under the Terms of Disbandment (HO 351/98 – HO 351/102). Under the Tribunal any policeman obliged to move his home both within Ireland or elsewhere was entitled to a disturbance allowance. By 1924 the Tribunal had dealt with ‘some 7,000’ accounts for disturbance allowance. A disbanded member could also apply to ‘load’ a pension for two years to ‘enable him to live and maintain his family without other employment’. Furthermore, it was possible to commute a portion of a pension to emigrate beyond Britain and Ireland, or even establish a business or purchase a farm.

The Tribunal ultimately considered 1,686 applications for emigration, approving 1,568, and granting 1,269 ‘home’ commutations – chiefly British (and Black and Tan) enlistments. Between 1922 and 1924 the Tribunal dealt with thousands of requests for increased disturbance allowances or commutation of pensions. It also awarded 1,263 grants for the ‘re-establishment of men forced to leave their homes’ whose personal effects had been damaged, stolen, or sold under ‘forced sale’ (see CO 762/1 and CO 762/212). Policemen who were forced to leave home without their wife and children could also apply for a separation allowance (see HO 45/13580).

Around the same time as the RIC Tribunal was deliberating, an Irish Distress Committee was constituted to help up to 20,000 refugees from Ireland with loans and grants. The refugees were a mix of RIC policemen, British ex-servicemen and civilians loyal to the British regime in Ireland. This committee was reconstituted as the Irish Grants Committee (IGC) in March 1923. By December 1923 the IGC reported that £11 million in grants had been supplied to refugees and £7.8 million of loans advanced. The IGC reported that it ‘had in this way resettled a considerable number of refugees in this country and had been able to arrange for the emigration of others to the Dominions (CO 762/212).’

Due to Conservative-led political pressure, a second IGC sat between 1926-31 to deliberate on applications for compensation by southern Irish loyalists who had suffered losses for remaining loyal to Britain. It was originally intended to exclude men assisted by the RIC Tribunal, but while the IGC could not deal with matters adjudicated by the Tribunal, applications by ex-RIC men for other losses were treated on merit.

Personal consequences

The case of Constable Jeremiah O’Sullivan (CO 762/82/10) illustrates the disillusionment and cynicism of the ordinary crown officer in the years after the conflict. O’Sullivan submitted an application to the IGC in January 1927. He had been disbanded in April 1922 and was forced to migrate to England under pain of death in May 1922, being joined by his family in August. In submitting his claim he was asked: ‘Do you claim that the loss or injury described was occasioned in respect or on account of your allegiance to the Government of the United Kingdom?’ He declared that he had received £39 disturbance allowance and £4.16 shillings separation allowance, as well as a compensation allowance of £138 per annum. The latter payment was effectively a pension. In his supporting letter O’Sullivan told of both his and his wife’s trauma by the IRA. His furniture from his Irish home had been burnt and his wife left a ‘nervous wreck’.

After being rejected for an award, O’Sullivan wrote an angry letter to the Chairman of the IGC pointing out that the statement ‘I have not missed a day’s work since July 1922’ was used against him. He was not given:

‘The opportunity of showing the nature of the work he had. Work the majority of men would shun for the sake of the dole. Why work, when had I been a waster for the past five years my case would in all probability have received a sympathetic hearing. Instead, I was told it was not required and politely requested to go outside … I have had a rude awakening from my day dream. It is the old, old story – some gain peace and power by loyalty and those who are less fortunate are sacrificed and have to keep on paying the penalty.’

He continued: ‘When the necessity ceased to exist [the loyalists] were left to the tender mercies of the IRA.’

O’Sullivan noted, or at least perceived, that treatment of individuals within the RIC was not always equal: ‘Men who got permits to return home from IRA officials and men who even held the rank of District Inspector and were accepted in the Civic Guards (the Free State Police) got the same treatment as men who were chased from place to place.’

The IGC archives illustrate that most ordinary ex-RIC did not receive any compensation for their allegiance to the Government of the United Kingdom. This, despite the fact that the RIC Tribunal itself admitting that pensions awarded to disbanded men were ‘in most cases insufficient in themselves to maintain the men and their families’ (HO 45/13029). Men such as Michael Egan from Cork (CO 762/9/5), for example, who had retired before being disbanded in 1922. Into the gap came private charity led by figures in the Conservative Party. The Southern Irish Loyalist Defence Fund, chaired by MP Captain Talbot Foxcroft, claimed to have helped both RIC refugees and distressed Irish loyalists. This organisation merged to form the Southern Irish Loyalist Relief Association (SILRA), which communicated with the RIC Tribunal throughout the 1920s.

Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that for the ordinary Constable, forced to flee Ireland or to re-locate either to Northern Ireland or another province, hardship was a consequence of being on the losing side in a war.

As usual, a very interesting and informative post, and one that throws a different spotlight onto the Royal Ulster Constabulary.