Welcome back to this, the second of my short series of blogs celebrating the 70th birthday of the NHS and taking a look at what records at The National Archives can tell us about its history. (Read Part 1: ‘Here is our chance to do something big’.)

Last time we left off with Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan toasting the Service’s success and the ‘smoothness of transition’ in a December 1948 Cabinet memo, five months after the NHS began operating.

Bevan’s success in getting the public – and eventually the medical profession – behind his new Service was, in part, due to the government’s mobilisation of a multimedia marketing machine. This ‘explanatory work’ was key in ‘creat[ing] public demand’, Bevan said.[ref] Difficulties between the Minister of Health and British Medical Association over the position of doctors etc. in National Health Service, 1948. Catalogue reference: PREM 8/844[/ref]

So, in the spirit of Bevan’s belief in the power of publicity – and to help try and sate Britain’s limitless fascination with 1940s and 1950s public information material – this blog post will take a look at propaganda from the NHS’ early days.

A letter from the Central Office of Information to the Ministry of Health regarding nursing recruitment, September 1952. Catalogue reference: MH 55/944

Government marketing was big business in the immediate post-war period. The wartime Ministry of Information was replaced by the Central Office of Information (COI) in 1946, but the COI was no less of a behemoth than its predecessor. In 1949, for instance, the regional offices of the COI staged 43,000 film screenings and 16,000 lectures around the country on topics ranging from how to increase productivity, to how to update your National Insurance details or sign up to train as a nurse. In 1945, COI films distributed to local authorities for showing in ‘non-theatrical settings’ (in other words, not in a cinema) were watched by an estimated 11 million people.[ref] Annual report of the Central Office of Information for the year 1949-50, Cmd. 8081, HoC Parliamentary Papers, Volume 10, 1950-1951[/ref]

Describing its approach to publicity concerning ‘social affairs’ (which the NHS fell under) in its 1949 report, the COI elucidated the three main aims of its health publicity.

Firstly, to stage ‘a positive programme of information directed towards the entire population or large sections of it about the provisions, benefits, opportunities and restrictions’ involved in the new service, explaining just what it was and what it did. Secondly they wanted to educate people on how to look after their health. Thirdly they sought to recruit health workers (although we won’t examine that today).

Explaining the NHS, nationally and locally

In the first instance, it was the ‘positive programme’ explaining exactly how one might use this new giant of British society that took precedence for the government’s publicity machine (the COI, although important, were not the only organisation involved).

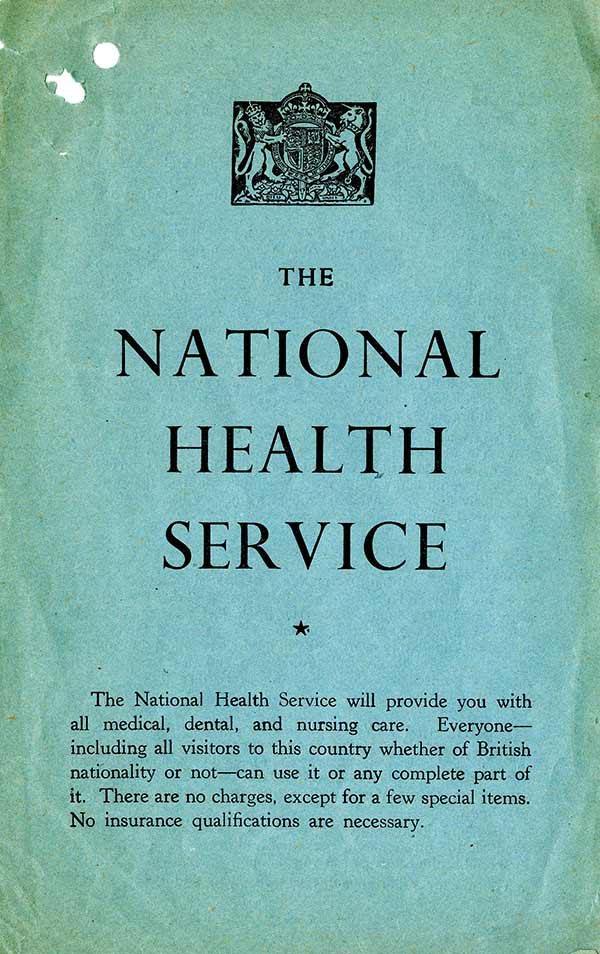

Government National Health Service leaflet, August 1948. Catalogue reference: BN 10/32

Leaflets like this one, issued by the Ministry of Health in August 1948, were a key part of such a campaign. It is a short, four-page pamphlet explaining the extent of the new services and how to access them. It opens with the – at the time – revolutionary statement that ‘everyone … can use it or any complete part of it … there are no charges’. Inside the details of dental, pharmaceutical, ophthalmic, maternity and other services are given. There is also a particular focus on ‘Choosing your Doctor’, as the core relationship between a citizen and their GP has always been at the heart of the NHS.

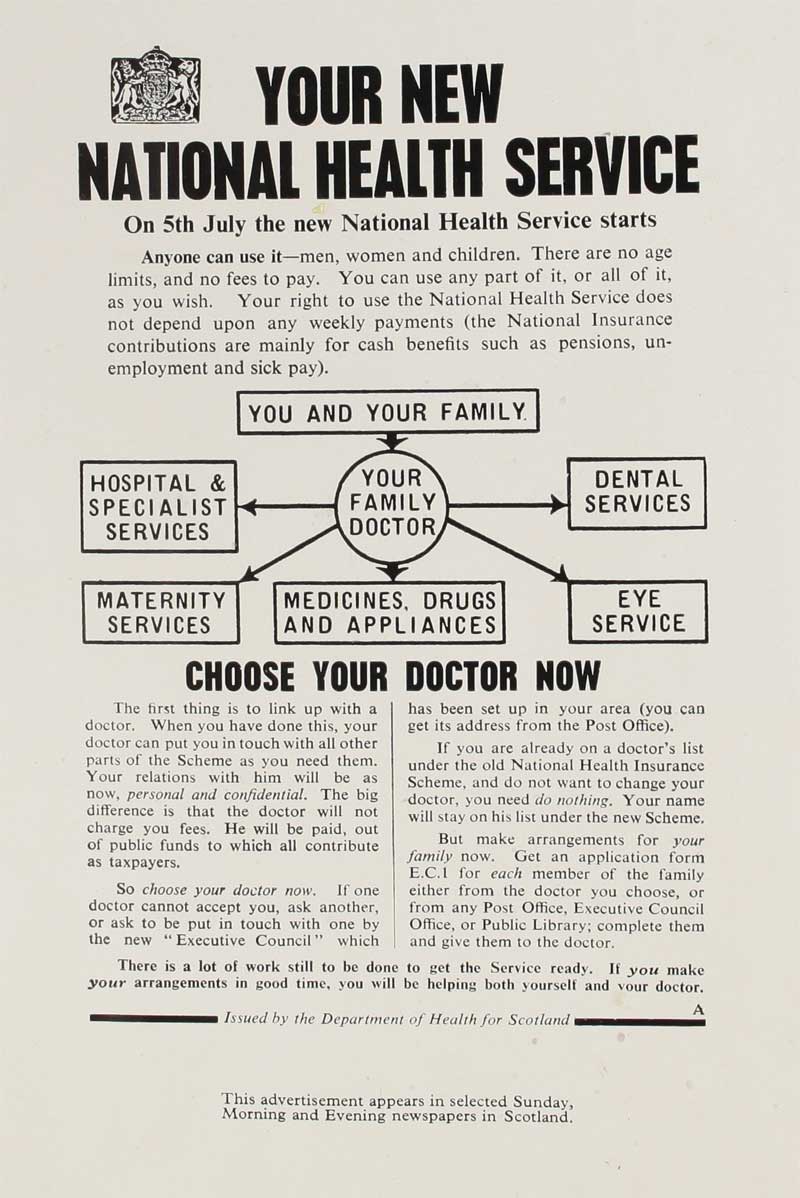

Your New National Health Service, leaflet produced by the Central Office of Information for the Scottish Department of Health, 1948. Catalogue reference: INF 2/66 folio 151

The focus on the central role of the family doctor to these new services is even clearer in this Scottish leaflet, put out before the NHS had started operating. ‘The first thing is to link up, with a doctor’, it tells us – that is the way to access all of the NHS’ ancillary functions. We can see the COI’s mission to get people to help themselves coming through, too, as the leaflet asks readers to help ‘yourself and your doctor’, as well as to ‘get the Service ready’, by filling in their forms in a timely fashion.

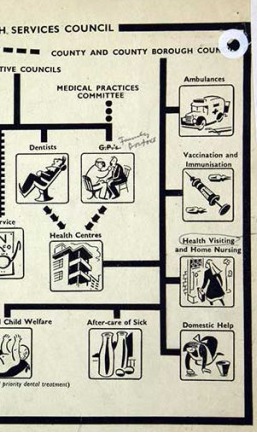

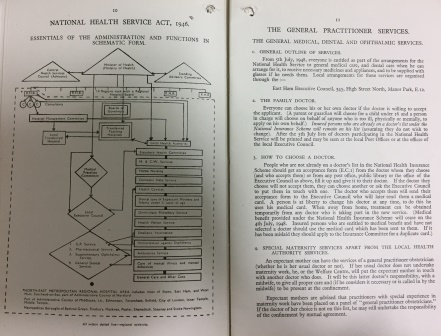

An excerpt from a diagram illustrating the chain of responsibility for the National Health Service produced by the Central Health Services Council, 1948-1949, highlighting the services local authorities were responsible for. Catalogue reference: HO 87/1599

Local authorities had a big role in providing parts of the new National Health Service, too, as shown by this government-produced organisational chart, with ambulances, vaccinations, home nursing, domestic help, after-care and child welfare falling under their watch.

Local authorities were expected to do their bit on the publicity front as well. ‘It will obviously be necessary to take steps to tell members of the public what services will be available’, the Ministry of Health wrote to the authorities of England; ‘Full use will be made of publicity through central sources but this cannot go into detail or give local particulars.’ Local authorities were asked to furnish their residents with detailed information. The National Archives holds several examples of these.[ref] Memo from Ministry of Health to all English local authorities, January 1848. Catalogue reference: MH 134/6[/ref]

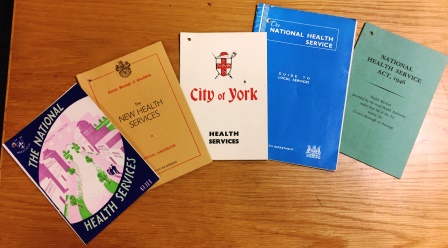

A selection of health service explanatory material produced by local authorities. Catalogue reference: MH 134/6

The guides range in length and complexity. Some are short and informative; others, like that of East Ham, are exemplars of both detailed public information literature and the utopian ethos of the post-war social settlement. The East Ham booklet’s foreword hails the NHS as an ‘epochal event in the conquest of disease and social evil’, before providing a short history of British medicine up until 1948.

NHS organisational chart and a guide on choosing a family doctor, from the East Ham guide to health services. Catalogue reference: MH 134/6

Photo of an immunisation and dental clinic from guide to Health Services in East Ham. Catalogue reference: MH 134/6

After the inspiration, the serious business begins with a thorough explanation of just what’s on offer. Like their central government counterparts, East Ham sought to demonstrate just who did what and reported to whom in the new NHS by producing an organisational chart. Again this was followed by a homily on the importance of choosing your family doctor. This is followed by details of all the ancillary services on offer, including timetables for therapy clinics and photos of the work being undertaken by the authority.

Was this publicity blitz successful? It seems so. As I related in my last blog post, 95% of the population were registered with the NHS before it started. In fact, it was so popular with a nation who had before contemplated the cost of medicine with, as East Ham put it, a ‘harrying anxiety’, that demand outstripped the government’s estimates.

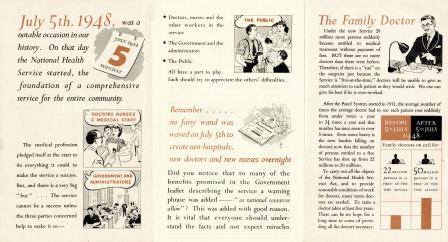

‘That then, is the cost of this social innovations’, wrote Aneurin Bevan to his Cabinet colleagues.[ref]Cabinet memorandum on the National Health Service by Aneurin Bevan, 13 December 1948. Catalogue reference: PREM 8/1486[/ref] But the Health Ministry sought to control demand through publicity as well, as shown by this 1948 leaflet, which cautioned an enthusiastic public that, ‘no fairy wand was waved on July 5th’ and advised how to take care of oneself.

The New NHS and You leaflet September 1948. Catalogue reference: MH 55/965

Since its birth was suggested by William Beveridge in 1942, the idea and the reality of the NHS have found a place in Britain’s heart. Seventy years on that is still much the same. Happy birthday to the NHS!

“Local authorities had a big role in providing parts of the new National Health Service”

Not quite, local authorities continued to provide

“ambulances, vaccinations, home nursing, domestic help, after-care and child welfare”

which had been

“under their watch”

for years.

Nothing new about such services.