Today (5 July) marks the 70th anniversary of ‘the appointed day’, 5 July 1948, when Britain’s new National Health Service treated its first patients.

Government National Health Service leaflet, August 1948. Catalogue reference: BN 10/32

Seventy years on, the NHS is firmly established as one of the cornerstones of the UK’s identity. However, the NHS’ birth was neither always smooth nor certain.

Before the NHS…

The NHS was not spontaneously created, but was the culmination of a long movement. Prior to the Second World War many people in Britain did not have access to proper medical care because they could not afford it. There had been widespread calls for the adoption of a scheme of universal, free-at-the-point-of-use healthcare since at least the beginning of the 20th century – there was a recognition that the costs of ill-health often left whole families destitute as their breadwinner recovered, and of the wider social problems this created.

Attempts had been made to extend free or affordable health care before – many working men subscribed for sickness benefits (a kind of insurance), voluntary and local authority hospitals provided health care to some of those in need, and the National Insurance scheme begun in 1911 provided a kind of safety net for the population. But these provisions were piecemeal and imperfect.

However it is William Beveridge’s 1942 report on ‘Social Insurance and Allied Services’, otherwise known as ‘The Beveridge Report’ (which I wrote about last year) which is typically seen as main catalyst for the creation of the NHS.

Frontispiece of the Beveridge Report, 1942. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2

Beveridge’s plan was to remake Britain after the war by setting up a comprehensive benefits system to end poverty. Underpinning this, he wrote, would be a free, universal system of healthcare. 1

‘The Beveridge Report and the Public’ survey. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2

Although the wartime Coalition Government worried about the expense, it became politically impossible not to commit to such a scheme. Government surveys found that 95% of the population had heard of the Beveridge plan and, what’s more, that 88% ‘heartily endorsed’ the idea of free medical services.

‘There is much agreement on what the aim should be, if not on the method of achieving it.’

What such a service would look like was, however, up for debate. Beveridge certainly wasn’t prescriptive. In 1944, the Coalition published a White Paper setting out their ambitions for a ‘comprehensive’ National Health Service. They acknowledged though that, while ‘there [was] much agreement on what the aim [of the new service] should be’, there was less agreement ‘on the method of achieving it’. 2

However, the 1944 White Paper did set out one of the more controversial parts of the NHS, acknowledging that, to be ‘comprehensive’, the new service must ‘cover the whole field of medical advice and attention, at home, in the consulting room, in the hospital or the sanatorium, or wherever else is appropriate’ 3. This would mean state control of the medical profession, and the doctors were not keen, taking umbrage at a removal of their independence and being cast as ‘salaried civil servants’. 4

Draft of the Coalition Government’s White Paper on a National Health Service, February 1944. Catalogue reference: CAB 66/46/24

‘Here is our chance to do something big’

In 1944, Cabinet had acknowledged the fact that their ‘control’ over them might be met ‘with keen opposition from the doctors’. However, they had believed that the row would die down, and that this control would be recognised as a way to increase ‘efficiency among the rank and file of the medical profession’. 5 But opposition was such that the two major parties of government, Labour and the Conservatives, took different approaches at the 1945 election.

Labour remained (vaguely) committed to the model set out in the White Paper: one with a degree of central government control. The Conservatives, meanwhile, had made some changes to their policy in line with doctors’ concerns. As health minister, Henry Willink addressed Churchill’s Cabinet just before the election; the Conservatives modified their plans to deal with medical criticism, setting out a vision of a service directed, not by Whitehall, but by local authorities and medical professionals themselves. 6

In the end, though, Labour won the 1945 election and their chance to establish a national health service, under the direction of Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan, who faced opposition from both doctors and his own Cabinet over the next three years.

Documents at The National Archives show that Bevan was a tough negotiator with a clear vision of what he wanted. When Cabinet raised concerns about private doctors not participating with the new GP service, Bevan’s solution was clear: ‘squeeze them out by creating better services … don’t prohibit them’. 7

Typed copy of Cabinet Secretary Norman Brook’s notes of the 20 December 1945 Cabinet meeting, discussing the NHS. Catalogue reference: CAB 195/3/83

It was Bevan’s commitment to a national service, with hospitals and doctors under its control, that made sure that Cabinet and the Labour government delivered it. In 1945, as the NHS was still in early germination, opposition from voluntary hospitals, doctors and local authorities to centralisation under a national service was fierce. Some in Cabinet wanted to delay the necessary announcement and legislation until a compromise could be reached, but Bevan insisted they continue. ‘Here is our chance to do something big,’ he told his colleagues; ‘Are we to sacrifice that chance for fear of the parish pump?’ The march of the NHS continued. 8

‘An attempt to completely sabotage it’

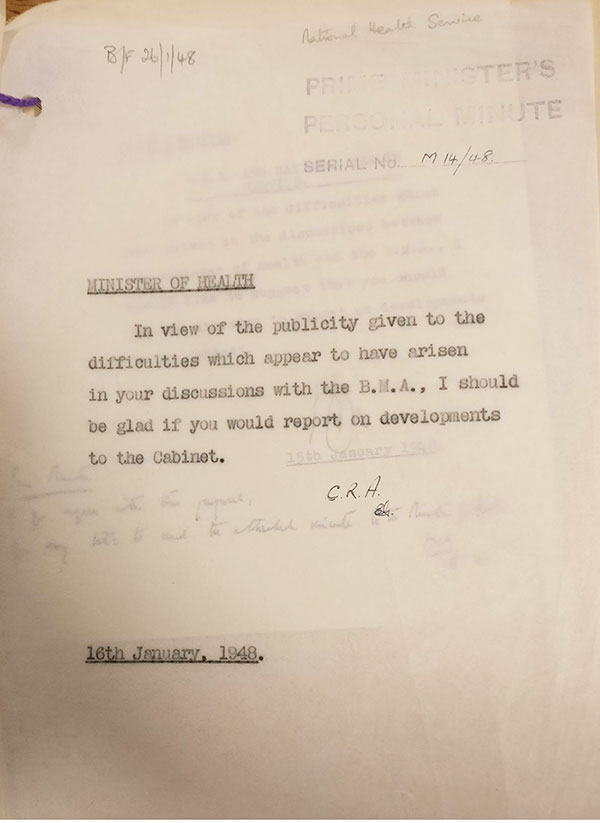

But still the opposition continued right down to the wire. In January 1948, just six months before the ‘appointed day’, the BMA’s committee passed a motion describing Bevan’s plan for the NHS as ‘so grossly at variance with the essential principles of our profession that it should be rejected absolutely by all practitioners’. They planned to get their members to vote, approving this statement.

Cabinet, and even Prime Minister Clement Attlee, were worried. However, Bevan was defiant. He said the BMA had disregarded the ‘facts’ in order to score political points against him. ‘It is quite clear,’ Bevan wrote, ‘that this is, on the part of the BMA, an attempt not merely to seek detailed improvements of the Act but to completely sabotage it and prevent its ever coming into operation.’ 9

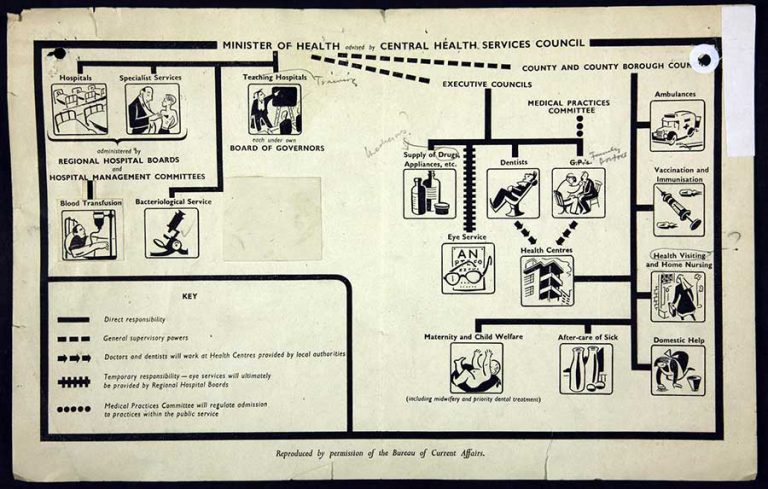

Bevan’s solution was, once again, to carry on. ‘I propose to build up accumulating evidence in the Press and elsewhere that the Act goes on, that I am setting up the machinery piece by piece and that they are not affecting progress of the preparations.’ He would create propaganda to convince the populace of the Service’s benefits, he said – this ‘explanatory work’ would ‘create public demand and thus affect the doctors’ position more and more if he sabotages it’.

Diagram illustrating the chain of responsibility for the National Health Service produced by the Central Health Services Council, 1948-1949, part of Anuerin Bevan’s “explantory work”. Catalogue reference: HO 87/1599

The NHS did, indeed, start treating people on 5 July, ‘the appointed day’, and Bevan’s approached proved successful. As he informed the Prime Minister in December 1948, around 90% of the population had signed up for the Service, while 85% of GPs had joined. The ‘smoothness of transition … has been truly remarkable,’ remarked Bevan. 10

The NHS was truly ‘something big’ then – but how did the government get the public and rank and file doctors to buy into the new scheme, when there was such opposition from the medical profession? Much of answer lay in Bevan and the government’s propaganda machine – the ‘accumulating evidence [to] create public demand’. I will explore this in my next blog post.

Notes:

- William Beveridge, ‘Social Insurance and Allied Services’. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2 ↩

- ‘Proposals for a National Health Service’, draft White Paper, 9 February 1944. Catalogue reference: CAB 66/46/24 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Difficulties between the Minister of Health and British Medical Association over the position of doctors etc. in National Health Service, 1948 Catalogue reference: PREM 8/844 ↩

- Cabinet Conclusions, 9 February 1944. Catalogue reference: CAB 65/41/17 ↩

- Cabinet notebook, 15 June 1945. Catalogue reference: CAB 195/3/44 ↩

- Cabinet notebook, 20 December 1945. Catalogue reference: CAB 195/3/83 ↩

- Cabinet notebook, 20 December 1945. Catalogue reference: CAB 195/3/83 ↩

- Difficulties between the Minister of Health and British Medical Association over the position of doctors etc. in National Health Service, 1948 Catalogue reference: PREM 8/844 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

Interestingly the publication (leaflet) says that anyone even from abroad could use the NHS for free in most cases.