To mark the centenary of the Somme Offensive we will be producing a series of blogs that explore the contribution of certain Commonwealth nations to the infamous land battle that has so dominated our perceptions of the British Army during First World War. When we talk about the First World War we have to remember that it was, truly, a world war; not only in the sense that fighting took place far from the western front but that people from all stretches of the globe took part in fighting far from their homes. The infamous Somme Offensive (popularly known as the Battle of the Somme) was no exception to this. From the hot climes of India to the tough wilds of Canada, people from all over the British Empire fought in this four and a half month ordeal in Northern France. This blog series will briefly explore the contributions of some of these nations through the collections here at The National Archives.

First up are the troops of Newfoundland, who were so badly affected on the first day of the Battle of Albert – the first action of the Somme Offensive.

In 1916, Newfoundland was a self-governing dominion in the same manner as Canada. Newfoundland would not join with Canada to become its 10th province until 1949. Thus, the men of Newfoundland did not join the Canadian Expeditionary Force but rather served in their own independent Newfoundland Regiment. The regiment itself was the size of a regular infantry battalion.

The Newfoundland Regiment saw active service at Gallipoli in 1915 and was part of the rear-guard that took part in the evacuation of Gallipoli on 9 January 1916. Following the evacuation, the Newfoundland Regiment transferred to the Western Front in March 1916 as part of the 88th infantry Brigade of the 29th Division. The war diary that covers the Newfoundland Regiment is available under the reference WO 95/2308/1. The Newfoundland Regiment was in the reserve line prior to the start of the Somme Offensive, and following the stoppages of the 86th and 87th Infantry Brigades, received orders at 8.45am to ‘move forward in conjunction with 1st Essex Regiment and occupy enemy’s first trench’.

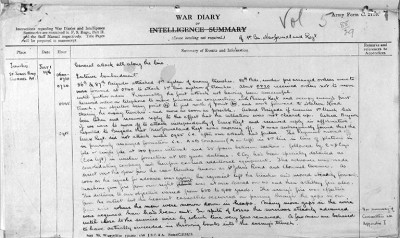

War diary of the Newfoundland Regiment on 1 July, the first day of the Somme Offensive (cat ref: WO 95/2308/1)

The Newfoundland Regiment was advancing steadily forward by 9.15am on the first day of the Battle of Albert. As the war diary indicates, the Newfoundland Regiment was on the receiving end of machine gun fire and artillery fire. This enemy fire is noted as having been ‘effective from the outset’ with the heaviest casualties for the regiment received whilst trying to pass through British wire. The diary graphically describes the men of the Newfoundland Regiment as being ‘mown down in heaps’.

The diary continues noting that ‘in spite of the losses the survivors steadily advanced’ and some may have even been able to throw bombs into the enemy’s trench. Despite this, by 9.45am it was clear that the attack had failed and the commanding officer reported this personally to Brigade Battle HQ some 100 yards behind the firing line. The number of men that would have gone over the top with the Newfoundland Regiment would have been around 720. Only 68 men would answer roll call at the end of the first day of the Battle of Albert.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates over 1.1 million men and women who served and died in the armed forces of its six modern-day member governments. An astonishing 243 men of the Newfoundland Regiment are recorded as having died on 1 July itself – this figure of course does not include those who died in the days following or even those who suffered life-changing injuries. Over 600 men were casualties and over a third of these men died. All within one day. As the war diary indicates, the devastation appears to have occurred within about 30 minutes (between 9.15 and 9.45am). For many of us, the horror of the First World War is most appositely demonstrated when studying the first day of the Somme Offensive.

The war diary for the 88th Brigade, WO 95/2306/1 suggests that the massive casualties suffered by the Newfoundland Regiment were mostly caused by machine gun fire. The loss of any life in these circumstances is the cause of incredible sadness and regret, and for many of us we can only imagine receiving the news that a loved one has died fighting in a major war. With this in mind, the story of one Newfoundland family really struck me during my research into the Newfoundland Regiment. When researching the names of the men of the regiment who died on 1 July 1916, I noticed that four men with the name ‘Ayre’ fell on the same day. Initial research indicated that one of the men did not appear to have an obvious connection with the others, yet three of the men – Captain Eric Ayre, 2nd Lt Gerald Ayre and 2nd Lt. Wilfrid Ayre – were first cousins. Aged 27, 25 and 21 respectively, all three men came from the capital of Newfoundland, St. Johns, and all three died on the same day.

Captain Eric Ayre’s commemorative record from the CWGC website states that he was the ‘Son of Robert Chesley Ayre and Lydia Gertrude Ayre, of St. John’s; husband of Janet Ayre, of St. John’s, Newfoundland. His brother Bernard also fell on the same day’. There was no Bernard Ayre who died in the Newfoundland Regiment on 1 July. However, it did not take long to find a Captain Bernard Pitts Ayre of the 8th Bn. Norfolk Regiment who died on 1 July 1916 aged 24 years old. Captain Bernard Ayre’s commemorative record indicates that he was the ‘son of Robert Chesley Ayre and Lydia Gertrude Ayre, of Brookdale, St. John’s, Newfoundland’ as well. So, four men from the capital of Newfoundland, two brothers and their two first-cousins dying on the same day in Northern France, over 4,000 kilometers from home.

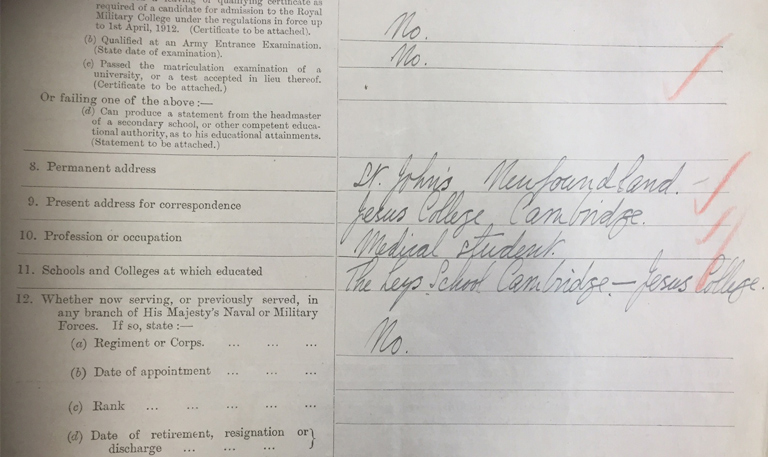

Officer’s service record of Captain Bernard Pitts Ayre (cat ref: WO 339/20790)

Despite being a Newfoundlander, as an officer in a British Unit, Captain Bernard Pitts Ayre’s officer’s service record is in The National Archives’ collection in WO 339/20790. The service record indicates that the St. John’s native had been reading medicine at Jesus College, Cambridge at the time he enlisted.

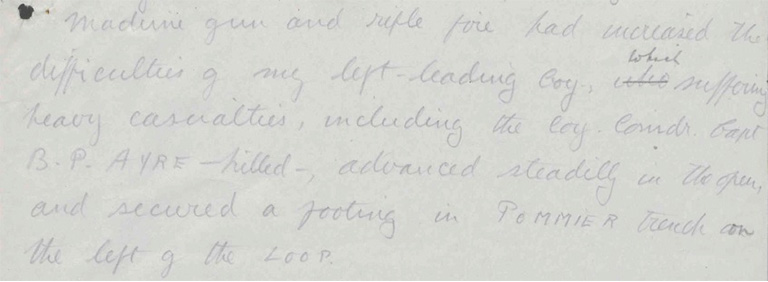

Despite being from the dominion of Newfoundland, Bernard was serving with the 8th Battalion Norfolk Regiment on 1 July. The 8th Norfolks were part of the 53rd Infantry Brigade in the 18th (Eastern) Division. Whereas Captain Bernard Pitts Ayre’s brother and his two cousins were based further north, taking part in the assault on Beaumont Hamel, he was with the 18th Division fighting from north of Carnoy up to Caterpillar Wood, west of Montauban. The battalion war diary of the 8th Battalion Norfolk Regiment, in WO 95/2040/1, indicates that shortly after 2pm – as the ‘left leading company’ secured footing in Pommier Trench – it lost its company commander, one Captain B.P. Ayre, due to an onslaught of machine gun and rifle fire.

War diary entry detailing the death of Captain Ayre (cat ref: WO 95/2040/1)

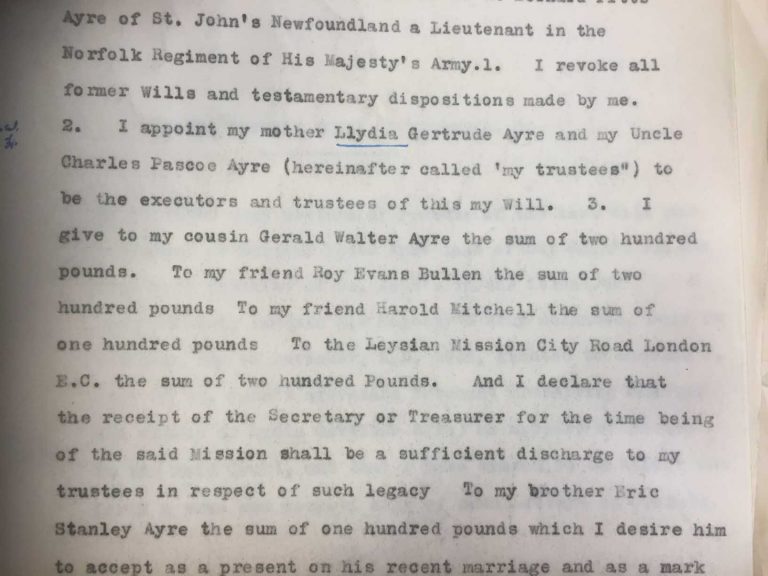

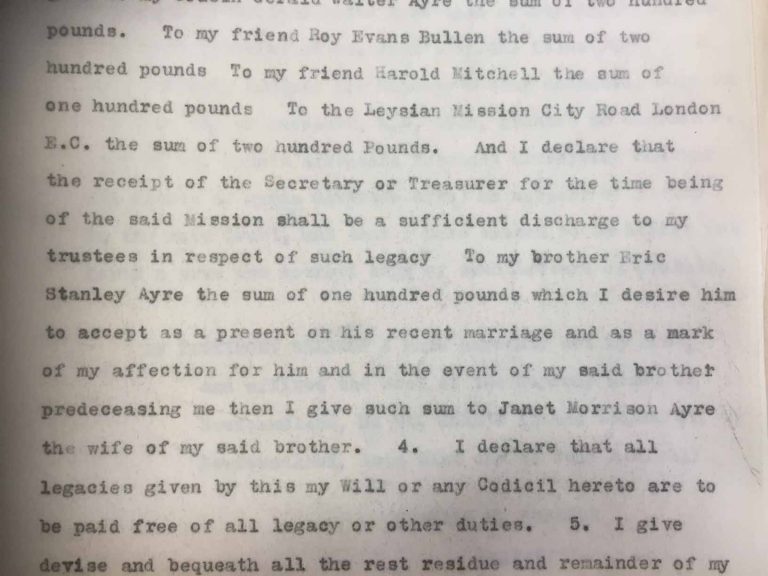

So following the death of his brother and his two cousins, most likely on the morning of 1 July, Bernard himself was dead by the early afternoon. His will is included in his service record, held by The National Archives, and it sadly indicates that in the event of his death, amongst others, it was Bernard’s desire to leave money to his brother Eric Stanley Ayre and his cousin Gerald Walter Ayre, both of whom fell that day.

Last will and testament of Captain Ayre, included in his service record (cat ref: WO 339/20790)

The sad truth of this first day of action at the Somme is that it would have been utterly devastating for the Ayre family, the people of Newfoundland and citizens across the empire.

The next blog in the series will pick up 14 days on from this devastating opening first day, and will focus on India and the experience of the 20th Deccan Horse at the Battle of Bazentin Ridge.

I have a memoir written by a relative who was in the Norfolk Regiment from 1914 to 1917 and was wounded on 1st July at the Somme. He relates an incident involving Capt. Ayre in the period leading up to the battle. Would this be of interest?

By all means, Mr. Hicks, please share the episode. There are many in Newfoundland like me who would glad of having the account.

I am related to Capt Bernard Ayre and would be very interested to hear the story you mention. Thanks for your excellent post.

Mr Fleming I follow your blog often with great interest. I truly admire the depth of your research and respectfully admire the personal comments on the Ayre family. Your reporting on the battle of the Somme, is immense. So much destruction of young lives and the misery caused to many many families. Well written so interesting.