On the night of 29 September 1939 details of civilians in England and Wales were entered on forms delivered to them earlier in the week.

The completed forms were ready and waiting for an enumerator to call back over the weekend and issue identity cards for everyone in the household. This was what actually happened in most cases, but there were some exceptions – there always are.

Unexpected responses

On the whole the operation went smoothly, as enumerators returned to all the households where they had delivered forms, checked through the details with the occupants and wrote out identity cards for each person there (they had a very busy weekend). Newspaper reports in the weeks and days following registration night portray an interesting picture of how the nation coped with this mammoth operation.

Most forms were collected without incident, but some enumerators reported difficulties finding the occupants at home, even after repeated visits. There could be extra problems in rural areas, with isolated houses, where the poor enumerator might have to climb over stiles and make their way along rough tracks and lanes. Fortunately the weather was generally good, so they did not have to contend with mud and rain, but no matter where they were, going around after dark brought its own hazards in the blackout.

Some responses were somewhat unexpected, such as the elderly lady in Leicester who said that she didn’t need to be registered because she was still on the books from National Registration in 1915, and produced her certificate of registration to prove it. A householder in Sheffield objected to completing the form:

‘This register is only an excuse to find out about other people’s business. I don’t believe there is a war on. And the blackout is only caused by the inefficiency of the lighting authorities.’

On the whole, good progress was reported in most places, but despite the best efforts of the authorities a small number of people were missed out from the initial survey. In the months after there were a number of prosecutions of people who had refused to register.

As the object was to get everyone registered, people were able to register at their local National Registration Office (NRO) if they had been missed out for any reason. However, once the household forms had been copied up into the register books any later registrations would go into a separate new register, the Current Register (which is not part of the 1939 Register release). So, sadly, a small number of people who were definitely in England and Wales on 29 September will not be found in the register, no matter how hard you look.

Criminal activities

In the past I have written about the introduction of civil registration in England and Wales, just over a century before this. I observed that when a new system is established there will be some confusion at the start, while everyone is trying to figure out what they are supposed to do, and some people will object on principle and refuse to comply. Then, once the system is up and running, some people will discover opportunities of making money from it. There are obvious parallels here. Advertisements soon appeared for ‘Rexine Wallets for holding National Registration Identity Cards’(Sheffield Evening Telegraph 7 October 1939). One enterprising company even applied for permission to use the royal arms on their covers, but were refused (HO 144/21329). Others offered identity discs and chromium wristlets.

For the dishonest or the downright criminal there were other possibilities. If you were registered twice, whether by accident or design, you could find yourself in possession of two ration books. It was a serious offence, but some people considered it worth the risk.

One young man who suffered from a heart condition found that he could make money out of his bad health by impersonating other young men at medical boards for a substantial fee, so that they could be exempted from conscription. Ten men were brought to trial for conspiracy in this case, including gang members ‘Buster Collins’and ‘Pongo’ (Nottingham Evening Post, 4 Jun 1940).

This is just one instance of the very serious issue of identity theft, and there were concerns about the potential for forging identity cards. The cards issued in 1939 were printed in black on plain buff card, and there were certainly attempts at forgery, although lost or stolen cards also had their uses. There were numerous cases of people on the run from the police, or who had deserted from the armed forces, being caught using another person’s card. Actual forgeries were usually produced by organised criminal gangs, like four members of a family in Northwood, Middlesex, who were arrested on another charge of fraud – but when their home was searched a number of forged identity cards were found (Gloucestershire Citizen 23 January 1941).

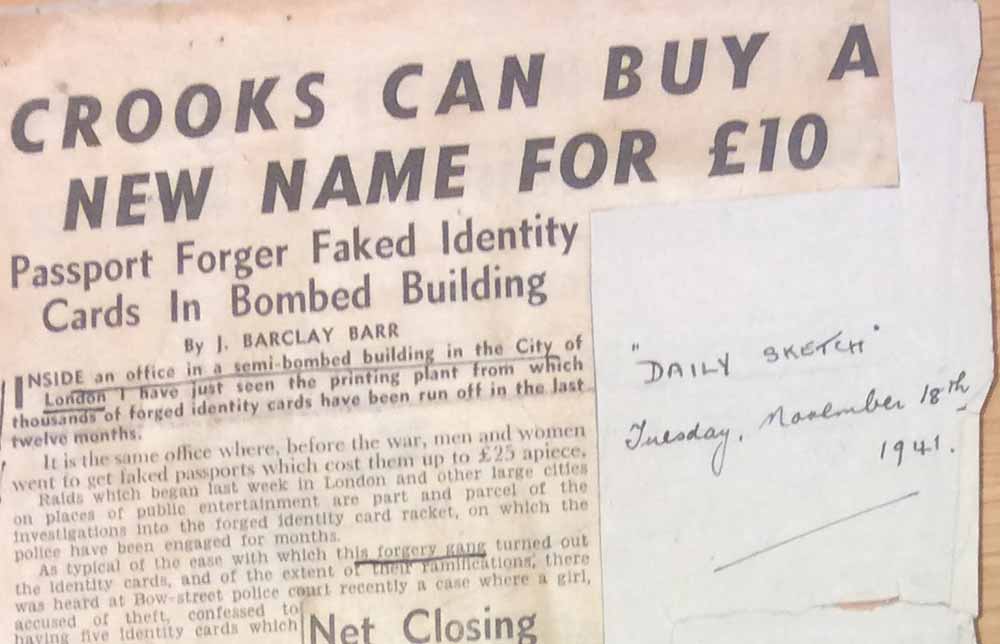

A story in the Daily Sketch in November 1941 caused great concern to the Registrar General, and became the subject of a whole file (RG 28/164).

Newspaper clipping (catalogue reference: RG 28/164)

Correspondence in rest of the file indicates that the details of the story were exaggerated, but this and other incidents demonstrate that there was good cause for concern. In 1943 there was a completely new issue of identity cards for adults, on blue card with elaborate background printing that was much harder to forge or even alter. Each card also had a serial number.

Marriage, death and burglary

Although there were clear instructions that any change of name had to be reported, it was found that a number of women simply changed the surname on their cards when they married. This was addressed by using widespread publicity, and asking marriage celebrants to remind new brides to report the change to the local NRO.

Everyone was required to carry their identity card at all times, and this was the first time that carrying identification became the norm, not the exception. A grisly, but useful, consequence of this was that it was much easier to identify a body when someone died suddenly, away from where they were known.

But one of the best examples must be the inept young burglar who dropped his wallet containing his card during a robbery, who was promptly visited by the police and arrested (Surrey Mirror 16 Feb 1940).

[…] On the night of 29 September 1939 details of civilians in England and Wales were entered on forms delivered to them earlier in the week. The completed forms were ready… Go to Source […]

I have been having a discussion with FMP about what I feel to be a shortcoming of the National Register transcription and wonder if you may be able to help plug the hole. Whilst many users are searching for specific people, others of us are engaged in one place studies and searching for everyone in a specific location. In the 1939 register, and just from my first toe dipped in, it seems a quite difficult and laborious task to unpick locations as there is no town/village/parish name given in the transcribed householder list or household address – and the municipal districts of the time were quite large geographically, especially the Rural Districts. I have found a work around via the advanced search but it is rather laborious. I wondered if any decoder or boundary information might be available for the ED Codes on the register, but FMP did not seem to understand the question or the need. If one exists, then it would have been great to have included the code in the householder list display, as well as the District field. Surely there must be one in with the main record set at the NA? Although too late for FMP to incorporate it, it would still be an incredibly useful reference tool to have access to online.

Unfortunately there is no easy way to identify small villages and hamlets in rural districts. The enumerators had Enumeration Books when they went on their rounds, containing a description of the district, a list of all the streets, hamlets etc, and a single line for each household. These were the equivalent of the Enumerators’ Summary Books in the 1911 Census (RG 78).

These books do not seem to have survived. They were not held centrally, and I have found no evidence that any have been kept at local level. I suspect that once the register books were written up, they would have been pulped and recycled, because they were no longer needed.

Interesting….. I’ve never forgotten my registration number, I think my parents must have drilled it into me the importance of doing so. At that time there were 4 in our family – dad four letters with 1, mum 2, me elder child 3, my sister 4. I was 7 years old. However in 1940 my brother was born*he didn’t become 5 but had an entirely new four letter code. I thought my card was blue?

* born indoors, both my mother and he straight down the Anderson shelter!

My card was issued in April 1951 & it is not blue, but buff with black lettering. It states on the front that it was for under sixteen, I was 7 when it was issued. I still have this card.