As digitisation conservators, we facilitate the digitisation of The National Archives’ collection. We survey and treat the documents before they are digitised, and we support the imaging teams by providing expert assistance and guidance.

The core principles of our work are to ensure that the imaging teams can safely handle the documents throughout the process, and to ensure that the text and images are legible and accessible. Our work combines minimalism and maximalism – we execute minimally interventive treatments, honed and refined through practice, which can be applied and modified across large-scale collections.

While working within this remit, we occasionally find pieces or collections which require a different approach. Such was the case with a set of volumes belonging to a digitisation project called State Papers Online Colonial: Asia, or SPOC: Asia for short. This project consists of British Colonial Office documents dating from the 1570s to the 1960s. They describe British exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries, leading to colonial rule in the 18th century, followed by countries seeking independence after the Second World War.

Built to last

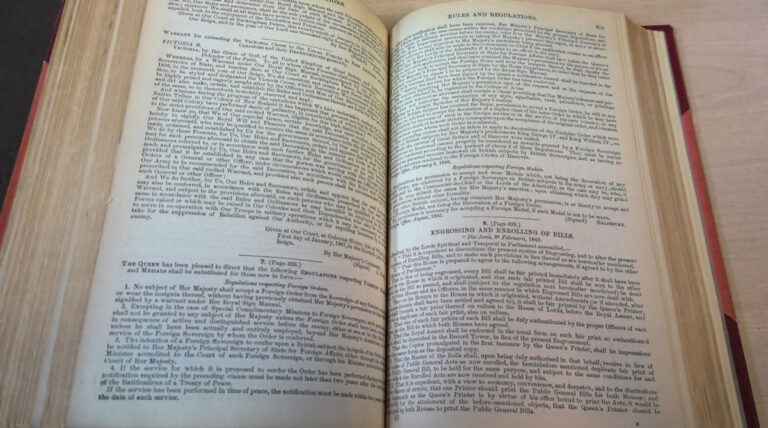

The volumes have been bound as library bindings, which is a structure developed to increase the durability and longevity of library books. Most pieces we work on belong to the archives at The National Archives, but these volumes are part of our reference library collection and are high-use documents, so they need to be strong. But these bindings were too strong for their own good, and we found that the opening was so tight that text was being lost in the gutter. As they were to be digitised, we wanted to reveal the text by easing the opening without causing damage to the volumes.

After discussions, we decided that partial disbinding – partially removing the covers and spine material while leaving the sewing intact – was the best option. As these volumes are reference lists containing information that relates to the entire project, it was important to capture everything.

Before we began treatment, my colleague Rhea conducted a survey of the volumes and, in collaboration with the imaging teams, was able to identify 10 volumes out of 55 that could be digitised without disbinding. My colleagues Solange and Rhea designed our overall approach to disbinding and rebinding the remaining 45 volumes, aiming to retain as much original material as possible, and to only alter what was necessary.

Our processes and technique

Since January, my colleague Keara and I have been working on these volumes. Here is an insight, via four steps, into the processes and techniques we have been using.

Step one:

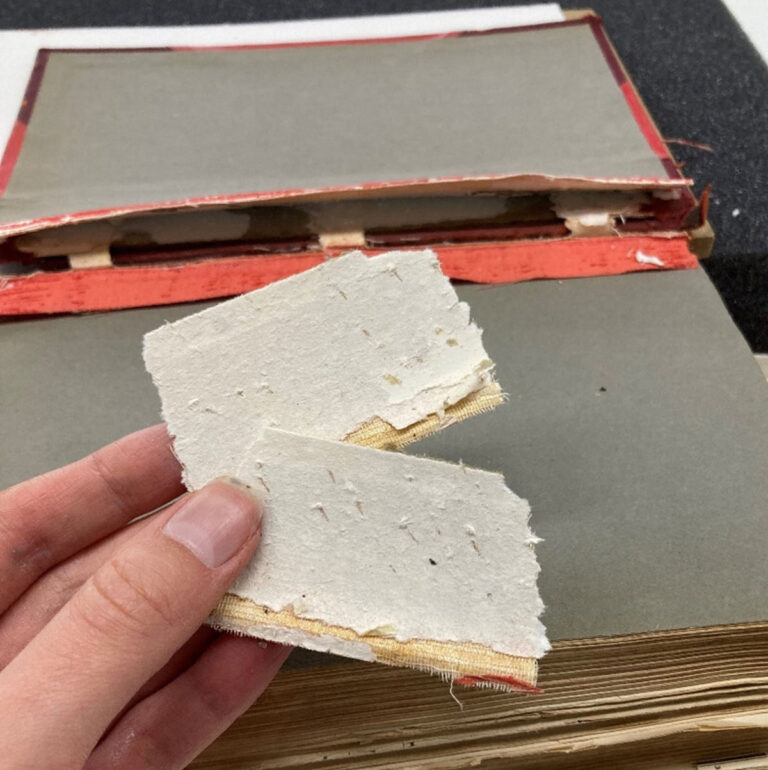

First, I lift the cloth over the joint at the back of the volume to access the material underneath. Library bindings have a stiff ‘packet’ made from spine linings and paper waste sheet, laminated with animal glue. This packet extends from the shoulder of the textblock and is adhered inside a split in the boards, which forms a very strong case attachment. To access the spine, I need to remove the packet from the split board. This work requires a long flexible lifting knife, a pair of long-nosed pliers, and a surprising amount of strength. On most of the volumes, I have been able to salvage the original tapes, which I can later reinsert into the split board to re-form the board attachment.

Step two:

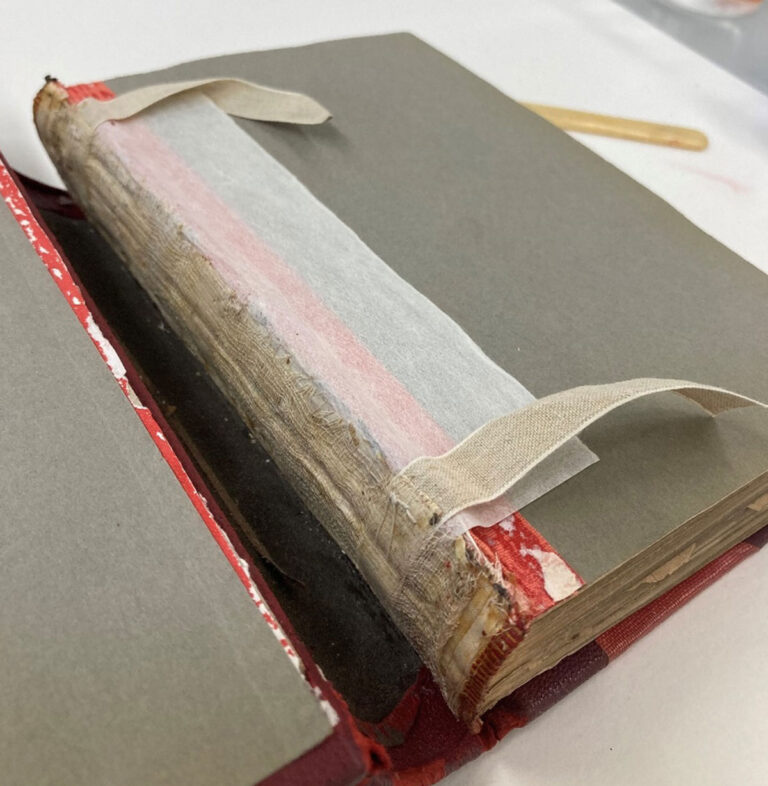

Once the packet and tapes are removed, I can access the spine. It’s here you can see why opening is so tight – layers of animal glue, mull (cloth), tapes and several layers of heavy grey card cover the spines of these volumes, making them rigid and inflexible. I use a poultice of methylcellulose to strip back these layers until I am left with the bare spine.

I retain the original cloth lining and tapes, which I clean to remove the brittle animal glue. They help provide strength and flexibility when reattaching the boards.

Step three:

Here, treatment pauses while the volumes are digitised. With their heavy spine linings removed, they can easily be opened flat the reveal the text in the gutter. They are, however, more likely to be damaged in this fragile state, so a conservator is on standby to assist.

Step four:

After the volumes have been imaged, they return to conservation for the final treatment stage, rebinding. I use a 28gsm Japanese tissue to line the spine, leaving a 30mm flange on one side which can be reinserted into the board to re-form the case attachment. I then adhere the original mull over the top. The Japanese tissue hinge and the tapes can then be fed back into the split board and adhered with wheat starch paste. The rebound volume is strong, flexible, and can be returned to its high-use environment in the library.

A good digitsation treatment will be repeatable across a large collection, yet also flexible. This treatment was applicable to the entire collection of library bindings, but could be adapted when different challenges or structures arose. For example, if the volume was particularly large and heavy, we used a heavier weight of tissue to provide more support. If the tapes were fragile or broken, we added tape extensions using new tape attached to the original with a three-hole saddle stitch. Not every volume had mull on the spine, so we looked for this and retained it when we found it. Although our work is large scale, we look at each object individually.

As with any digitisation project, there are logistics. Because these are high-use volumes belonging to The National Archives’ library, we have agreed that we will only ever work on six volumes at a time. Since October 2022, my colleagues and I have worked on 31 volumes and will work on 14 more before the project is complete. It has taken significant organisation, skill and hard work to pull this project together, but it has so far been a success.

These stages start with selection, acquisitions processing, cataloguing and pressmarking and go through to preservation, conservation, storage, retrieval and the de-accession of duplicates.

It’s really inspiring to see the thought and care that goes into digitising bound volumes – thank you!