The guns fell silent on the Western Front on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918, heralding an end to the war after four long years of bitter fighting.[ref]This is the form of text that is usually cited on Armistice Day and on Remembrance Sunday. [/ref]

The Armistice with Germany was signed at 05:00 in a railway carriage in the Forest of Compiègne, about 70 kilometres north of Paris. Six hours later, at 11:00, the war ended.

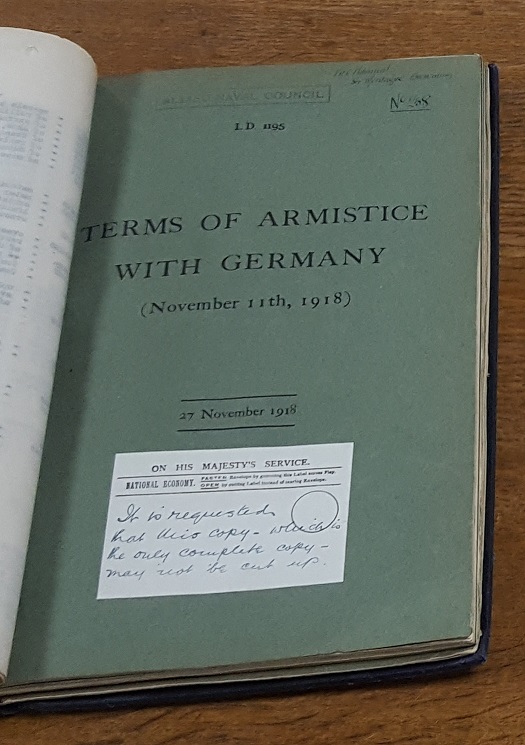

Terms of Armistice with Germany. This is the Admiralty’s official copy. Catalogue reference: ADM 116/1931

The armistice terms demanded the immediate cessation of warfare and surrender of the fleet and of heavy guns and aeroplanes. German troops had to withdraw to the east bank of the Rhine within 30 days, and a neutral zone would be established there to a depth of 30 to 40 kilometres. Allied troops were to be allowed to occupy strategic positions throughout Germany, at the expense of the German government.

Among other key conditions, all Allied prisoners of war were to be returned and all German ships were to return to port to be decommissioned. Selected U-boats and battleships were to be surrendered, with the remainder of the German fleet to be disarmed and placed under the jurisdiction of the Allied countries.

Repatriated Prisoners of War arriving at Hull from Rotterdam 17 Nov 1918. Catalogue ref: ZPER 34/153 Illustrated London News July – December 1918

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed with the Russians in March 1918, was revoked; so was the Treaty of Bucharest, made with Romania in May 1918. This reduced Germany’s territory and political and economic control to its pre-war status. Additionally, the province of Alsace-Lorraine – taken from France as a result of the Franco-Prussian war of in 1871 – was to be evacuated, and all German forces operating in East Africa were to withdraw.

How did the armistice come about?

Several overtures of peace were made by Germany from 1917 onwards, but these were largely dismissed by the Allied leaders as fishing attempts to test the Allied resolve. It was not until January 1918, when President Woodrow Wilson addressed the American Congress with a 14-point programme for peace, that things began to be taken seriously (FO 608/148).

On 4 October 1918 Max, Prince of Baden, the Imperial German Chancellor, sent a note to President Wilson stating:

The German Government requests the President of the United States of America to take in hand the restoration of peace, acquaint all the belligerent states with his request, and invite them to send plenipotentiaries for the purpose of opening negotiations. The German Government accepts the programme set forth by the President of the United States in his message to Congress of the 8th of January 1918 as a basis for peace negotiations. With a view to avoiding further bloodshed, the German Government requests the immediate conclusion of an armistice on land and water, and in the air. (FO 608/148)

President Wilson’s 14 points sowed the seeds for discussion, but they had not been drawn up in direct association with the Allies. At a meeting in Versailles on 29 October 1918, between the French and British Premiers and their Foreign Secretaries and Colonel House, President Wilson’s adviser, the first of many days of debate dedicated to drawing up an Armistice began. Armistice terms proposed by Marshal Foch were considered alongside those of President Wilson (FO 608/148).

The signing of the armistice

On 7 November 1918, the German delegation came across the lines bearing a note from Woodrow Wilson which led them to believe that they would be welcome to discuss peace terms with the Allied leaders. On 8 November they were taken to the Forest of Compiègne, where there was a railway dining carriage which had been converted into a makeshift conference room.

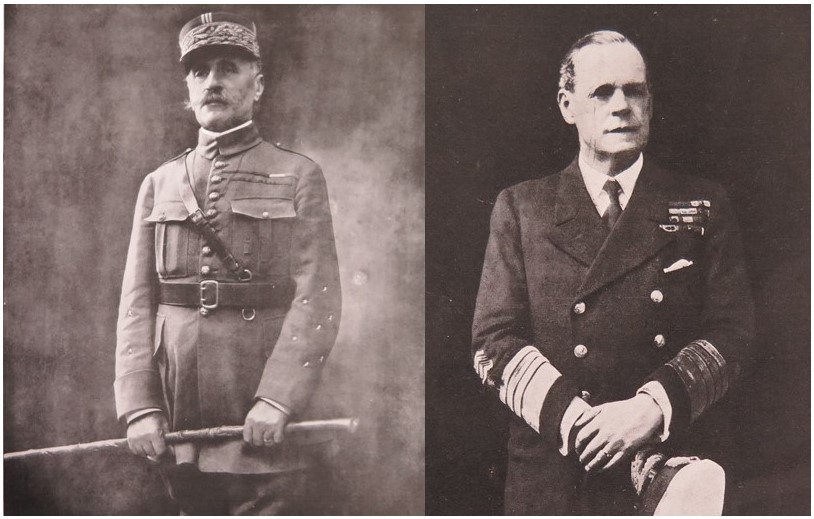

The French and British officers present were: Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies, General Weygand, Chief of Staff, Lieutenant Laperche, Interpreter, Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir George Hope, Deputy First Sea Lord, Captain Jack Marriott, Naval Assistant to the Chief of Naval Staff and Commander Walter Bagot, Interpreter.

Marshal Ferdinand Foch and Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, signatories of the armistice on behalf of the Allies. Catalogue ref: ZPER 34/153

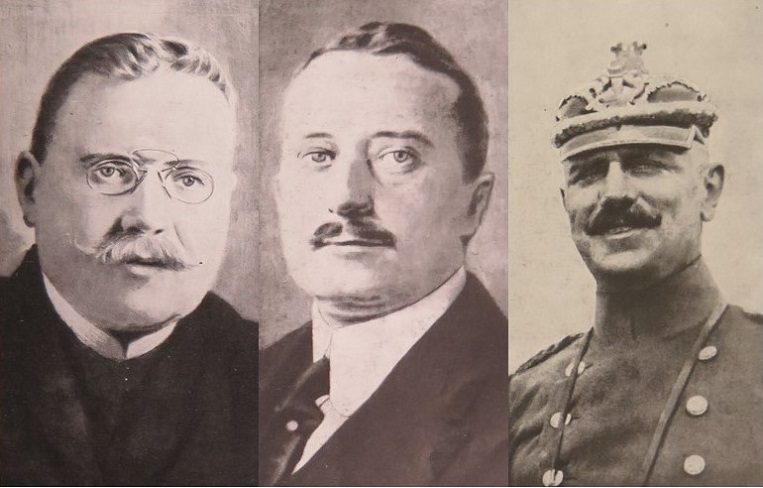

The German delegates were Mathias Erzberger, German State Secretary and Vice Chancellor, Count Alfred von Oberndorf, representing the German Foreign Ministry, Major General Detlof von Winterfeld, representing the German Army, Captain Vanselow, representing the German Navy, and two interpreters, Hauptmann Geyer and Rittmeister von Helldorf.

Erzberger, Oberndorf and Winterfeld, the principal German negotiators at Compiègne. Catalogue ref: ZPER 34/153

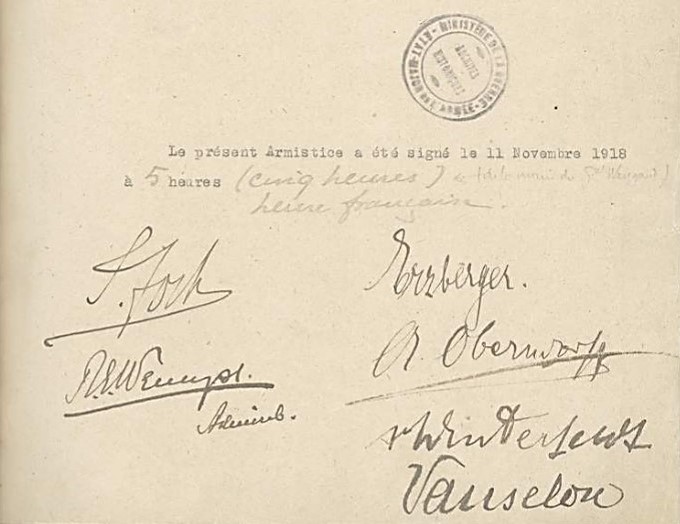

The original copy of the Armistice Convention, bearing the signatures of the Allied and German plenipotentiaries. This document is held by the Service historique de la Défense (SHD) which is the Archives of the French Ministry of Defence. Reference: FRSHD GR 15 NN 32

We can get a good impression of the negotiations that took place between the German and the Allied delegations from an unofficial account written by Walter Bagot (ADM 1/8546/319). Here is an abridged version, which makes for fascinating reading:

On Thursday 7 November, 1918 the British Mission boarded Marshal Foch’s train at Senlis station. The train arrived at some old heavy gun sidings in the middle of the Forest of Compiègne about 7pm and remained there during the whole negotiations. The German mission did not arrive until the early hours of Friday morning. On the arrival of the train containing the German delegates, Marshal Foch sent over a staff officer to say that he would receive them at 9 o’clock.

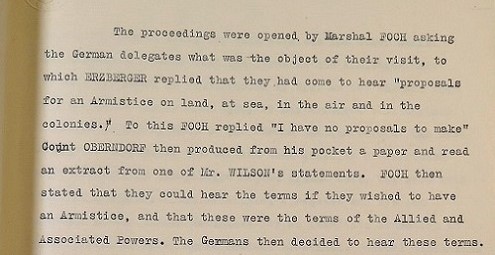

The proceedings were opened by Marshal Foch asking the German delegates what was the object of their visit, to which Erzberger replied that they had come to hear proposals for an Armistice on land, at sea, in the air and in the colonies. To this Foch replied “I have no proposals to make.”

Extract from Walter Bagot’s unofficial account. Catalogue ref: ADM 1/8546/319

Count Oberndorf then produced from his pocket a paper and read an extract from one of President Wilson’s statements. Foch then stated that they could hear the terms if they wished to have an Armistice, and that these were the terms of the Allied and Associated Powers. The Germans then decided to hear these terms.

General Weygand began the reading of the principal articles of the terms of Armistice. The French interpreter translated each article into German as it was read. The proceedings were conducted in French. Erzberger spoke only in German, although he appeared to know enough French to be able to follow.

A request was then put forward by the German delegates for an immediate cessation of hostilities, so as to avoid useless bloodshed. Marshal Foch informed them that no cessation of hostilities could take place until the terms already read had been accepted and signed. [The delegation would have 72 hours to make up their minds].

The Germans then retired with copies of the terms to their own train, the proceedings having lasted about an hour and a half. About lunchtime Captain Helldorf, carrying the terms of Armistice, departed in tears for the German headquarters at Spa.

At about 02:00 on Monday 11 November, the German delegates arrived for the final conference. The procedure was for General Weygand to read out the terms, article by article. The French officer interpreter then translated each article into German and then, where necessary, the final form of the article was decided upon.

When the reading of the terms had been completed, Erzberger rose and read out a declaration in German. In this he stated that the German government would do everything in its power to carry out the terms. The German plenipotentiaries, however, desired to point out that some of the terms were so harsh as to be likely to bring about a state of anarchy and famine in Germany.

The proceedings came to an end about 05:00 French time. The various documents were then signed first by Foch and Wemyss and then by the four German delegates. Orders were then issued for a cessation of hostilities on land and at sea and in the air at 11:00 French time on 11 November, the duration of the Armistice being 36 days from that hour.

About 06:00 the commandant of the train produced a bottle of port and some biscuits. A toast was drunk to the great event. At 06:20 Marshal Foch and Admiral Wemyss left for Paris by car to lay down the terms of Armistice before the French Government. The train carrying the Germans left for Paris about 10:00.

Admiral Hope and myself left for Paris about 10.30. As soon as the outskirts of Paris were reached it was evident that everybody had heard the good news. Everybody was buying flags and decorating their houses with them, and by lunchtime the people of Paris were marching about arm in arm crying La Victoire! La Victoire!

Celebrations

The War Cabinet met at 09:45: the Prime Minister announced that he had received a message from France stating that the Armistice had been signed and that hostilities were to cease at 11:00. They decided that a press announcement should be made at once, and that all necessary steps should be taken to celebrate the news by the firing of maroon flares, the playing of bands, the blowing of bugles, and the ringing of church bells throughout the kingdom. They also decided that the order prohibiting the striking of church and other public clocks should be at once rescinded (CAB 23/14/46). As a result, Big Ben tolled for the first time in four years.

In London, crowds spontaneously gathered around Buckingham Palace and Trafalgar Square. In Piccadilly Circus, people danced in the streets and formed huge conga lines. A thanksgiving service was held in St Paul’s cathedral on 12 November, attended by King George V and Queen Mary. On 19 November the King and Queen addressed both chambers of the Houses of Parliament, addressing them and through them the nation and the Empire, upon the triumphant conclusion of the hostilities.

Aftermath

On 28 November 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II, already in exile, signed the deed of abdication at Amerongen, in the Netherlands. An Armistice Commission was set up at the Grand Hotel Britannique, in Spa, Belgium, formerly the German Imperial Army Headquarters. It was from this hotel that the Kaiser had started into exile on 9 November. The Commission was established to ensure that Germany was keeping up with its obligations established under the Armistice Convention.

On 18 January 1919 the Peace Conference was opened in Paris. It was to last for six months until the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. The treaty was only ratified on 10 January 1920. As a result, the Armistice terms, which were initially to last only 36 days, were prolonged three times, until the treaty finally came into effect.

In a memorandum written in April 1919, Francis Clarke, an official at the War Office, noted with prescience that: ‘The future observance of the treaty by Germany will depend ultimately upon the attitude not of the signatory delegates but of the German nation as a whole, which will develop according to the development of other circumstances. The power of one generation to control the fortunes of the next, whether by the promotion of high ideals or by the construction and maintenance of military and economic power, is easily exaggerated.’ (FO 608/143)

Under Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany had to acknowledge responsibility for all the loss and damage to which the Allied and associated governments and their nationals had been subjected to as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by German aggression. The treaty imposed punitive reparations, with Germany required to pay 132 billion gold marks (US$33 billion) to cover civilian damage caused during the war.

The German people saw reparations as a national humiliation and came to see themselves as victims. The uncompromising terms of the Versailles treaty undermined the legitimacy of the newly-elected Weimar government. This opened it to attack from the extreme right and left. Communist, nationalist and fascist movements in Germany grew in strength and began to enjoy a new level of popularity. The denunciation of the Versailles Treaty was one of the platforms that gave Hitler’s Nazi Party credibility with mainstream voters in the early 1920s and early 1930s. (FO 954/10A/150)

Remembrance

Official celebrations did not take place in London until 19 July 1919, when a bank holiday was declared and a Victory March took place in the capital.

Victory parade passing Buckingham Palace. Catalogue ref: WORK 21/74

The parade passing the cenotaph. Catalogue ref: WORK 21/74

Nevertheless, the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month has taken on a special significance in the post-war years. For the majority of Allied nations who took an active part in the war, the moment when hostilities ceased on the Western Front has come to symbolise the end of the war and provide to an opportunity to remember those who had died.

Related events

- The Eve of Peace: join us on Saturday 10 November for a day of talks and activities to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War. Find more information and book tickets.

- Words of Peace: until Friday 7 December 2018 we are displaying two iconic documents relating to the end of the First World War – the armistice terms and the Treaty of Versailles. Find out more.

- Copies of all of the armistices and treaties that were signed with the Central Powers will be shown together for the first time during the conference ‘Peace making after the First World War’ taking place from Thursday 27 to Friday 28 June 2019.

- Service historique de la Défense (SHD), which is the Archives of the French Ministry of Defence, is holding a wide-ranging exhibition about the Armistice of Compiègne. It highlights the original document signed by Maréchal Foch and Admiral Wemyss, as well as the four German representatives. You can read more about this event on the Service historique de la Défense website (in French).

A very good blog. I thought that Germany (Prussia0 only took over the northern part of Lorraine after the disasterous (to France) of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. It may have a historical irony that Compiegne is where Jeanne d’Arc was captured and where General Weygand signed the surrendered to the Germans in 1940. The Germans, not to put too finer a point on it, did understandably resent the ‘War Guilt’ clause in the Peace Treaty and started fighting after the Armistice and were planning to enter the new country of Czechoslovakia. The burdens imposed on Germany were to my mind (with hindsight) wrong as did John Maynard Keynes (the Economist, who worked at the Treasury and suddenly left after the Peace Treaty was signed) Britain was just as much to blame for the damage on Ypres (Ieper) as the Germans were and the only people that made good out of the war were the arms manufacturers, one of whom bankrolled the Nazi Party until they turned against him, the company still exists today. One of many problems after the Armistice was the large numbers of men to be demobbed and jobs which women had occupied during the war and the large gaps in the number of men that women could marry due to the number of men who died in the war and of course the financial cost of the war.

Interesting blog the statistic which I believe is missing is that while the generals and politicians dithered between the signing of the armistice and it coming into effect there were a further 2,738 people killed. All died unnecessarily and it is a remarkable epitaph to the failure of the War to end all Wars to do just that.

I found this very informative. I now truly understand what it is all about. I must admit that I am concerned however, that very little is said about the colonial input at the frontlines. My grandfather, a Jamaican, Frederick Dowie, (born in Kingston Jamaica, in the 1880s, later married to Sarah Dowie), has completely been written out of the British written history about World War one and two. I am nearly sixty years old and when a child in school. I only saw photos and pictures of European men at war.

I only realised Jamaican men went to war very recently. My mother’s older’s sister told me my maternal grandfather served, not in the second world war but in the first.

I was shocked. I had no idea because when taught about the wars, we only saw

pictures of white men. I feel it is crucial for historic organisations like the National Archives show a show a true reflection of how these wars were won. What was the make up of the colonial forces. India is an enormous country. How many Indians served in World War one? How many African soldiers served in world war one? How many Caribbean and so on. The British ‘needed’ the colonies to help them win. They were low in numbers. They could not win it on their own. So, that truth should be reflecetd here too. It also helps Caribbean, African and Asian peoples feel connected to Remembrance Day. Armistice iI have now discovered, is not only about England but it is also about the people of the ‘colonial territories’. These men too, should be shown (not in a back corner as if of no significance but alongside all others. The war was one because of the numbers of soldiers from all the colonial territories. Of course they were used. We all know that. Most were killed at the frontline but, a few, returned home like my grandfather Frederick. He went on to marry my grandmother. The couple had six children. The story of Caribbean contribution to the war must be included for it to be a rounded true story. Omission is a form of deception. Many Jamaican boys and men lost their lives fighting in the Crimean, World War One and World War Two. The National Archives have a responsibility to reflect the true history.