The festive season is often filled with wonder and excitement. Presents bought for loved ones are carefully wrapped in colourful paper, beautiful boxes and fancy fabrics. They are eagerly unpacked in anticipation of the treasures found inside. Usually seen as a strong box for the nation’s written heritage, The National Archives, equally a repository of many wonderful objects, contains some marvellous textile wrappings that have largely gone unnoticed.

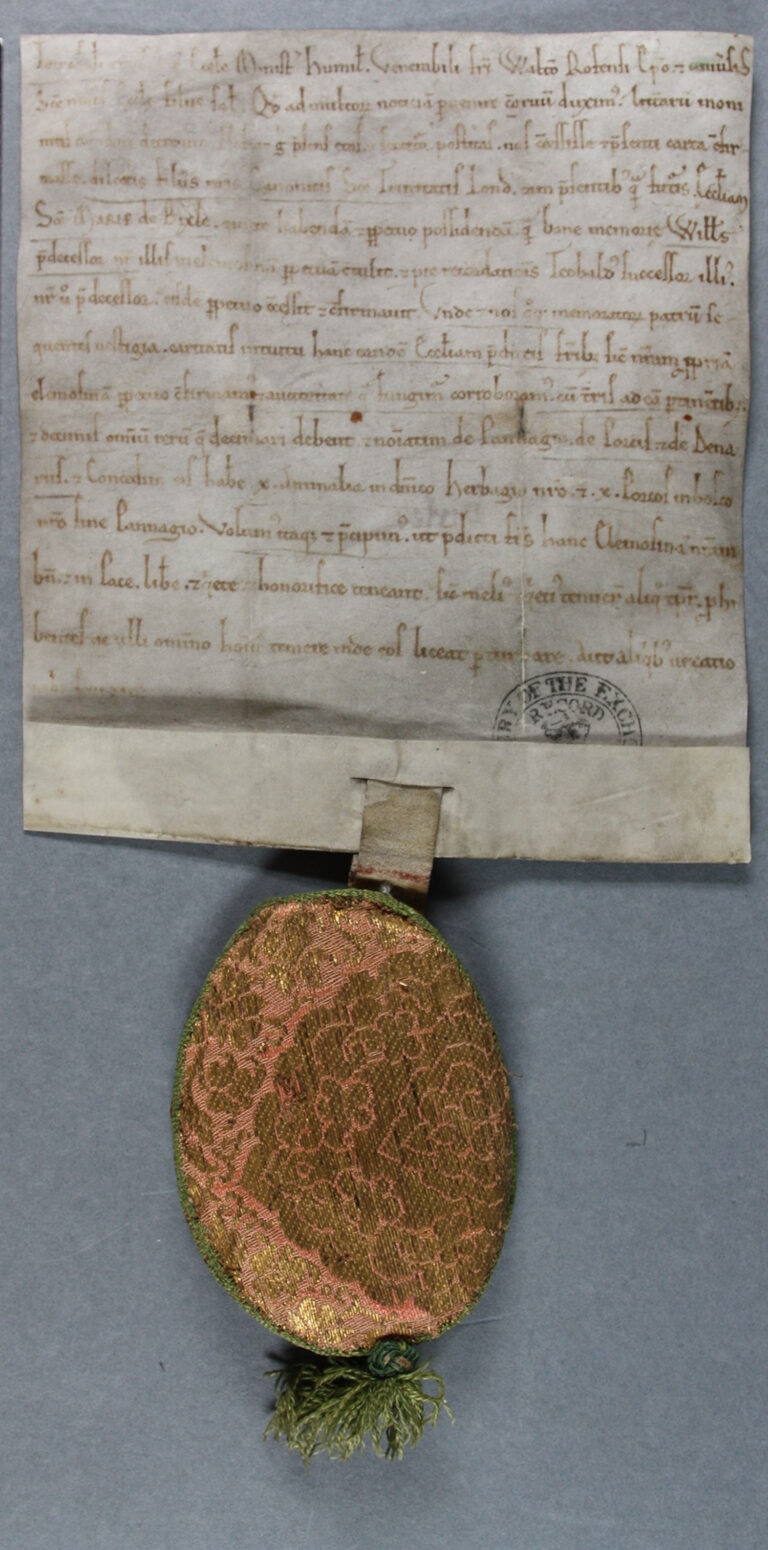

Known as seal bags or seal wrappings (see footnote 1), they are used to cover (and so protect) medieval wax seals that are appended to charters, those formulaic texts which give details of grants of land and property rights in the past. Seals were a means of verifying the identity of the sender and legally authenticating the document’s contents.

Perhaps the most famous example in our collection is the stunning precious gold and pink-red mussel-shaped silk envelope preserving the seal of Thomas Becket, appended to a confirmation of a grant of land to Holy Trinity Aldgate Priory in London in the 12th century.

This glistening wrapping, no bigger than one’s hand, invites the unpacking of what is carefully preserved inside. The two parts are sewn together only at the top by a few stitches. Putting the green tassle attached to the bottom into motion, the wrapper opens. Then emerges a bright red oval-shaped wax seal of about 7.5 cm high and 5.5 cm wide. It contains a small impression on the reverse of an antique figure surrounded by the inscription, or legend, in Latin: “Sigillum Thome Lund’”, that is “Seal of Thomas of London” (see footnote 2). So, this object is the personal seal of Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury killed in his own cathedral just after Christmas 1170 by supporters of King Henry II.

The pink-red and gold silk on the outside and the unadorned red lining match the red seal perfectly, suggesting that the soft wrapping was selected consciously. In its closed state, the high status of the seal owner is underscored, even amplified. Upon opening this fleshy mussel-shaped envelope, the viewer is enthralled by the pearl preserved within: the impression of Thomas Becket’s seal for which an ancient gem had been used, possibly representing the winged Mercury, the Roman god who acted as a messenger for all other gods. This exotic silk cover simultaneously hides its contents and highlights that these must be precious.

King Henry VIII’s dissolution of monasteries like the priory of Holy Trinity Aldgate in London, where this document was once kept, makes it hard to trace the wrapper’s full history (see footnote 3). Yet the textile itself provides some clue. Frances Pritchard established that the material is a panni tartarici from the second half of the 13th or early 14th century (see footnote 4). So Becket’s seal could have been wrapped up around 1300. Panni tartarici (or Tartar cloths) refers to Eastern Islamic silks woven with gold and silver thread (see footnote 5). In fact, a detailed image of the textile shows the characteristic type of metal thread used in these fabrics: gilded animal substrate, i.e. gut.

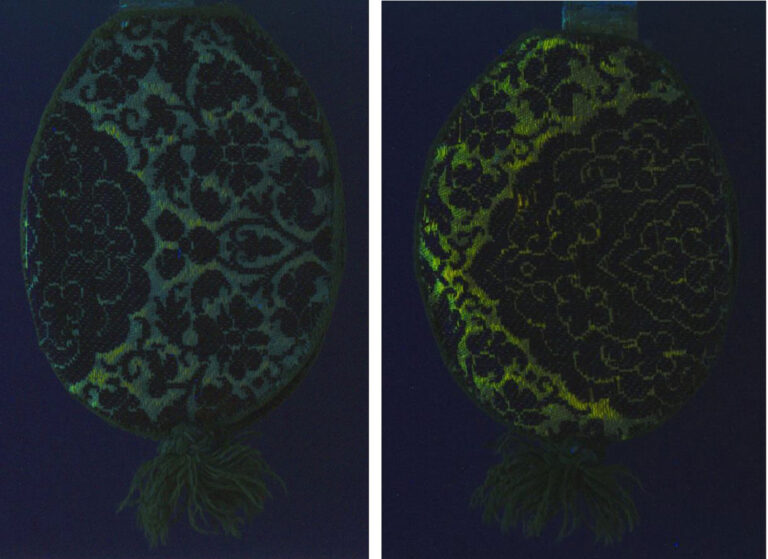

In addition, dye characterisation, using non-invasive techniques such as Multispectral Imaging (MSI) and Fibre Optics Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS), revealed that the pink-red colour used for the outside of the wrapping was made of safflower. This yellow, orange, or red dye is extracted from a plant that grew in China, India and Egypt, thus confirming the origin of the fabric. This is also evidenced by the floral pattern in the shape of a lotus.

Luxury fabrics like panni tartarici were highly appreciated in Europe’s elite circles (see footnote 6). Before being made into a small wrapper the fabric was likely part of a larger textile, but to date no identical designs are known for it. We cannot establish whether the bag was made from a left-over textile or a repurposed garment. But it would not have been hard to find exquisite silks at Aldgate Priory or its environs.

Undoubtedly such lavish and precious textiles, which were signs of social distinction, would have been used for the manufacture of ecclesiastical garments. Ecclesiastical dress could fall out of fashion or was simply worn down, but never would it be just thrown away. Instead, they were repurposed into seal bags and perhaps even pouches or horse trappings.

Seal wrappings were primarily meant to protect seals, but luxurious examples like the Becket one suggest that documents were deliberately distinguished visually in order to highlight their historical and institutional importance. We can imagine visitors to the priory being shown the sparkling bag with its important ‘treasure’ (documenting key rights) inside, and examining it in awe. In Becket’s case, we may speculate that the canons of Aldgate considered the seal to be a relic. Touched by the archbishop himself when he pressed his seal matrix in the warmed, softened wax, the seal had become a tangible reminder of the martyr-bishop.

Such an important piece deserved a worthy cover, comparable to glistening metal shrines that house the bones of saints. An expensive panni tartarici, perhaps once part of the kind a vestment Archbishop Becket would have worn, was the perfect choice. Even more so when we take into account that the vestments Becket wore when he was murdered became relics themselves. The Metropolitan Museum in New York owns a reliquary pendant, which according to its engraved inscription originally held Thomas Becket’s garments stained with blood (see footnote 7).

To the canons of Aldgate, who would have been familiar with the story of Becket’s martyrdom and the rich vestments worn by priests, the pink-red bag with its deep red lining may have reminded them of Becket’s blood, and it was perhaps a device on which they would contemplate his sacrifice.

Still, many questions regarding seal wrappings – both precious and mundane – remain to be unravelled. For example, when were wrappings attached to the sealed documents? Are seal bags a northern European phenomenon, and if so, why? And what are the weaving techniques and materials of these sometimes sumptuous textiles? Have the original colours faded over time and, if so, what was the original appearance of these wrappings? How can The National Archives (and others) best preserve, describe and disseminate these fascinating but fragile covers?

These and other questions are at the heart of the project “Out of the Bag. Unravelling Medieval Seal Bags through Cultural Studies and Scientific Analysis”. Please reach out to us via the comment button if you know of seal bags in other (European) collections. Have you found references to such wrappings in medieval written sources (inventories, lists of expenditure, chronicles), or are aware of similar textile designs?

In the spirit of the holiday season we do appreciate your gift of knowledge!

This project is funded by the The National Archives’ Strategic Research Fund 2022-2023 (ref. 514 – SRF project “Out of the Bag”). We are grateful for the expertise provided by Ana Cabrera, Paul Dryburgh, Elizabeth New and Frances Pritchard.

Footnotes

- For example The National Archives, DL 10/51; E 42/524; E 42/529; E 42/531

- Joseph Butt, “Confirmation by Thomas, Archbishop of Canterbury, of the Church of Bexley, Kent, to the Canons of the Holy Trinity London,” Archaeological Journal 26 (1869), 84-9. For a recent description of the seal, see Lloyd de Beer and Naomi Speakman, Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint (London: The British Museum, 2021), 22.

- On Aldgate, see John Schofield and Richard Lea, Holy Trinity Priory, Aldgate, City of London: An Archaeological Reconstruction and History. MoLAS Monograph 24 (London: Museum of London, 2005).

- See her description of the wrapping in Holy Trinity Priory, Aldgate, City of London, 15-17.

- Anne E. Wardwell, ‘“Panni Tartirici”: Eastern Islamic Silks woven with Gold and Silver (13th and 14th centuries)’, Islamic Art 3 (1988/89), 95-174.

- Lisa Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III”, Textile History 32 (2001), 2-35.

- Neil Stratford, “Reliquary Pendant of Queen Margaret of Sicily”, in English Romanesque Art 1066-1200 (exh. cat. London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1984), 283

Hello, thanks for a terrific blog post. In response to your call for examples of medieval seal bags, I wanted to share the one we have cataloged in the Index of Medieval Art database as system no. 94307 (https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=97357480-5AC3-4E18-ABB7-8E10A891A859). It’s attached to British Library Additional Ch 75724, the seal of Bordesley Abbey, 1141-1142. You may know it already, but just in case.

The Index will be going public in July, as you may know, but if you have trouble accessing it before then, please be in touch. We’re happy to help.

Beautiful, how wonderful these objects are, a window into our past and stimulant to learning more of our history and how we came to this place.

Thank you for this stimulating post! A fascinating subject. In my recent Speculum article, I address seal bags, in particular the making of seal bags from textiles that had previously been in use as vestments. The article is online here with free access: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/715820

fascinating article. it looks as if the silk seal cover is lined with red silk, and the two fabrics are stitched together using blanket stitch. this is a simple stitch, still in use today for binding the edges of fabrics – this may be the first recorded example.