This year, the focus of The National Archives’ First World War Centenary programme shifts to the use and development of technology. Medicine is one of the areas that we will be exploring and so today’s post is designed to give a brief overview of the route which wounded or sick soldiers would have taken when receiving treatment.

Having been injured, wounded or taken sick on the Western Front, British and Commonwealth soldiers would have received their initial medical treatment at a Field Ambulance unit, from where they would either be returned to their unit or sent further back to a Casualty Clearing Station for further care.

From a Casualty Clearing Station the injured would be moved back further towards a Base Hospital before potential transportation home to a British military or civilian hospital. This journey would come to see a wide variety of transportation methods utilised, ranging from stretcher bearers, horse-drawn carriages, motorised vehicles, barges and ships of various shapes and sizes.

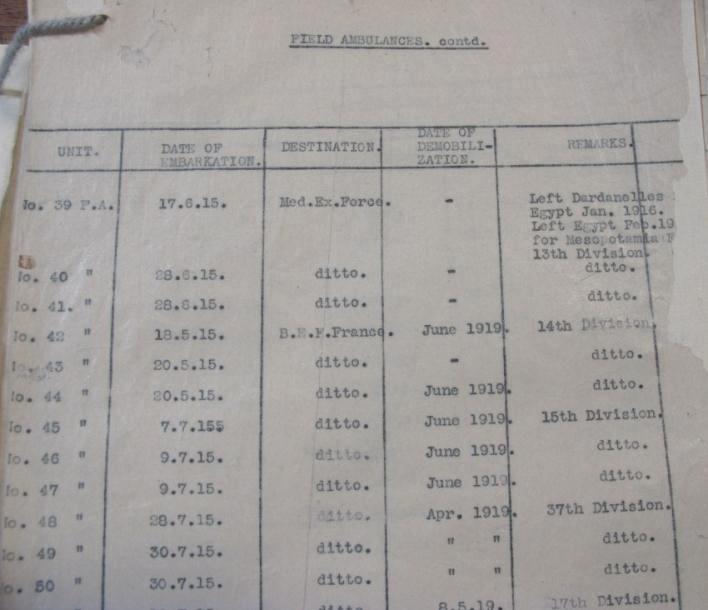

WO 95/5494: Locations of medical units, listing Field Ambulance units, Casualty Clearing Stations and other hospitals.

From a research perspective, discovering the medical units or hospitals that your ancestor may have been treated at can be quite difficult. A service record, if it survives, may contain details of medical units which treated a wounded or sick soldier. Alternatively, if you know the Division that your person of interest was serving with, this can help identify the three Field Ambulance units attached to that formation. I would also recommend consulting the ‘Location of Medical Units’ found within WO 95/5494. This folder details the various medical units and hospitals in numeric sequence by hospital type. In some cases the Division attached to, location, and relevant dates are recorded.

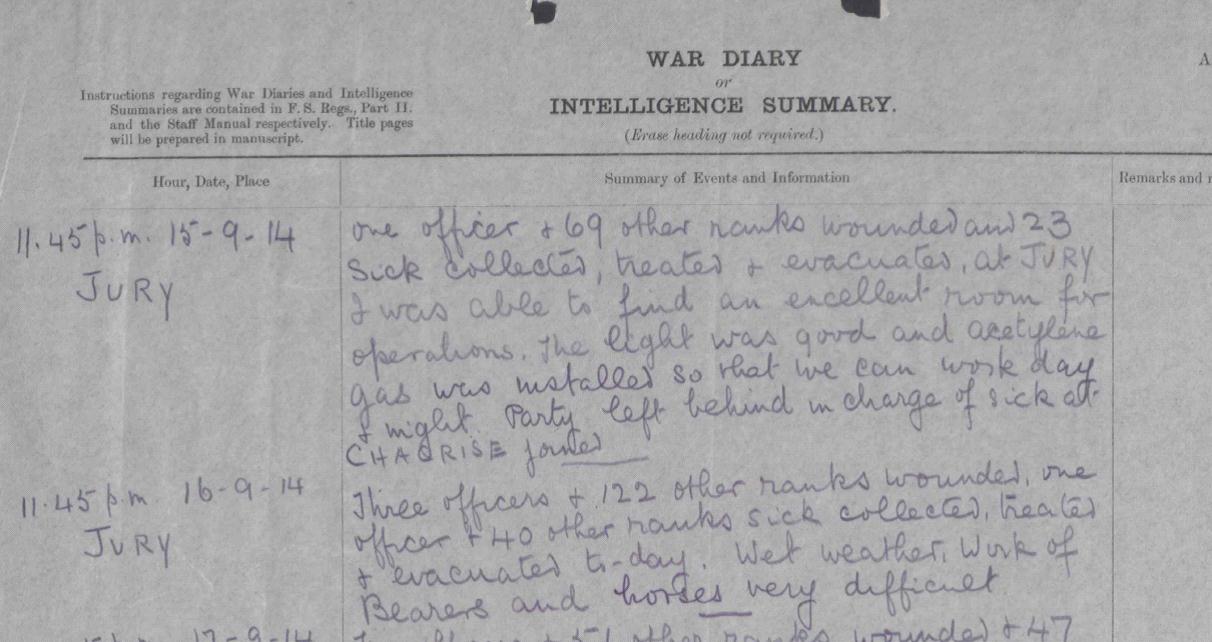

In terms of records of these various medical units and hospitals, our First World War unit war diaries clearly show the demanding, hectic and dangerous day-to-day work carried out by these units. For example, the diary of the 14 Field Ambulance on 10 September 1914 describes how the stretcher bearers came under enemy artillery fire on the road leading to the dressing station at Passy. Later that same day the bearers returned to the front lines to collect the fallen and entitle them to a dignified burial. The entry for 15 September reveals the discovery and use of ‘an excellent room for operations’. Crucially, the ‘light was good; acetylene gas was installed so that we can work by day and night’. Perhaps we neglect the basic challenge of maintaining light or heat at advanced positioned medical units during the early stages of the conflict (WO 95/1540/3).

WO 95/1540/3: War diary of 14 Field Ambulance showing the use of acetylene gas to provide lighting for operating room.

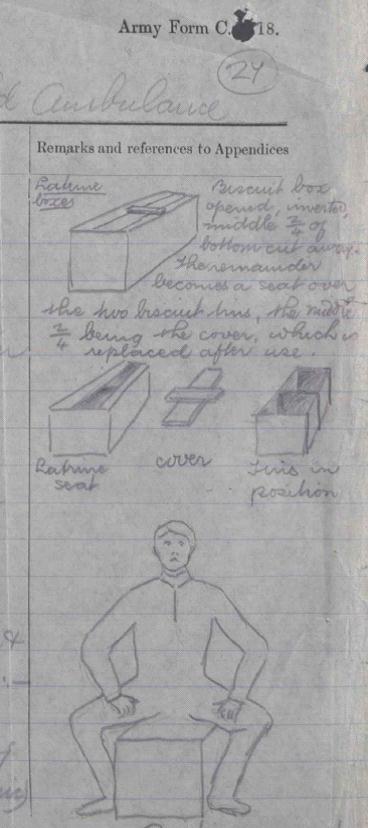

WO 95/1703/1: 24 Field Ambulance war diary, July 1915. Sketches showing how to turn biscuit boxes into latrines.

Field Ambulance war diaries can also highlight the pressing need for improved and disciplined sanitary conditions, to reduce the spread of disease or infection. The 24 Field Ambulance, for example, improvised the re-use of biscuit tin boxes to create better latrines for the patients and staff, as demonstrated by diagrams in their July 1915 war diary (WO 95/1703/1). This example points to the fact that improved equipment or conditions for troops, the wounded, sick and medical staff, did not always require a technological first or new invention. Simple improvisations combined with a bit of imagination could help improve local conditions for troops, which in this case may have limited the threat of disease or illness.

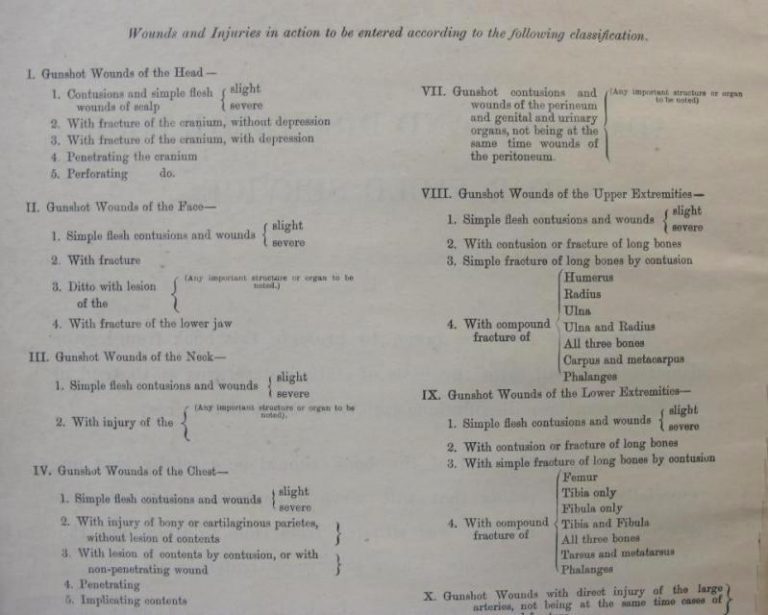

Our MH 106 collection consists of a representative sample of First World War medical papers, including admission and discharge registers to selected Field Ambulance units, Casualty Clearing Stations, Base and Home Hospitals. Although only a 2-3% sample, these registers record each patient who was admitted during the period covered by each volume, noting the name of the soldier, nurse or civilian admitted; unit; squadron, battery or company; regimental number; rank; age; years of service; type of wound or disease; religion; and dates of discharge, transfer or death.

As well as the battlefield wounds suffered by soldiers, with the horrific nature evident on a classification sheet at the start of each register, the spread and impact of different illnesses or diseases amongst troops is also notable. With these records being a selective sample from across the various theatres of war, as well as the various nationalities forming the Allied fighting force, the registers may indicate possible patterns in the contracting of and spread of certain infections.

MH 106/279: Admission and discharge registers of selected First World War medical units. Each register contains a classification of wounds key sheet, highlighting the horrific nature of some injuries.

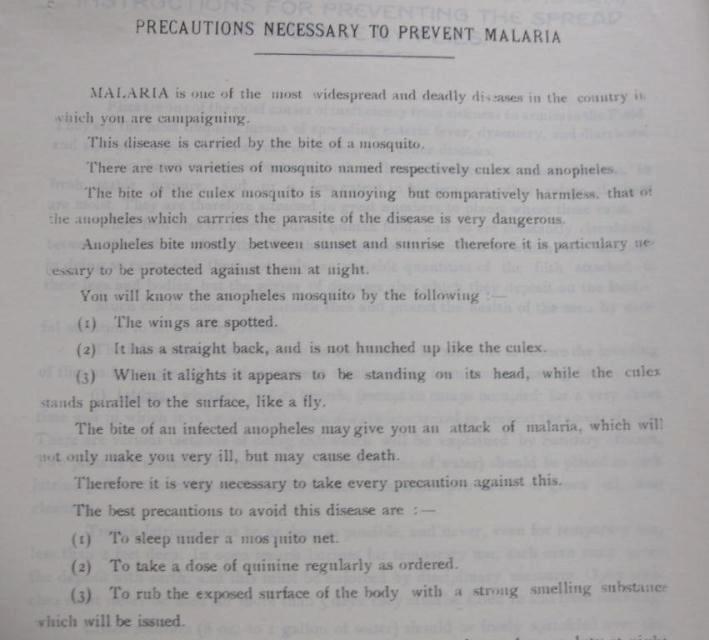

The hygienic discipline expected of the troops began at the front lines rather than in medical units, however, with a perfect example found in the war diary of the Adjutant and Quartermaster General, Salonkia. A copy of instructions to troops on tackling malaria provides tips on how to identify the more dangerous ‘anopheles’ mosquito which had spotted wings. The use of a mosquito net, taking a dose of quinine ‘regularly as ordered’ and by rubbing ’the exposed surface of the body with a strong smelling substance which will be issued’, were also recommended to troops (WO 95/4765).

WO 95/4765: War diary of the Adjutant and Quartermaster General, Salonika, April 1917. Instructions on how to prevent malaria.

In medical terms, technological advances, such as new medicines and equipment would have a very significant impact on the care, treatment and rehabilitation of wounded during and after the conflict. We hope to explore some of these advances in greater detail throughout our series of blog posts, so do watch out for the next one in February from my colleague, Vicky. What is evident when researching the experiences of various medical units, however is that disciplined sanitary practices and the innovative yet simple use of materials could lead to improved conditions for the wounded and sick during their journey through the various stages of medical care.

Hi, I’m researching the Endell Street Military Hospital. I’m interested in tracing specific patients who went there, including their service records. What would be the most efficient way of finding these? Do I need individual names? And I’m also interested in any information on the convoys – which ones went to Endell Street and where those wounded had been sent from.

Many thanks for any help.

Hi Wendy,

Thank you for your comment.

If you go to our contact us page http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat – I hope that helps.

Nell