Seventy years ago today, on 30 September 1951, the Festival of Britain took down its bunting, stacked up its chairs and closed its turnstiles. It had opened on 3 May 1951 to a degree of scepticism about the cost and the expected benefits. But in reality it proved to be a great success which left an enduring legacy still evident in modern day design.

Back in May we celebrated the anniversary of the Festival’s opening by filming different people reflecting on the Festival and its continuing influence. Naomi Games spoke about her father Abram, the iconic graphic designer responsible for the Festival emblem; Paula Day spoke about her parents Robin and Lucienne, the inspirational furniture and textile designers; Mini Moderns design duo spoke about the influence of the Festival on their work; and our own Katherine Howells (Visual Collections Researcher) spoke about the amazing collection of documents, photographs and artwork that we have at The National Archives. You can watch the videos here.

I thought that on the anniversary of the closing I would take this opportunity to write about some records we haven’t highlighted before, but which give a new perspective on the behind-the-scenes stresses and strains of organising such a huge event.

London fruit and vegetable markets

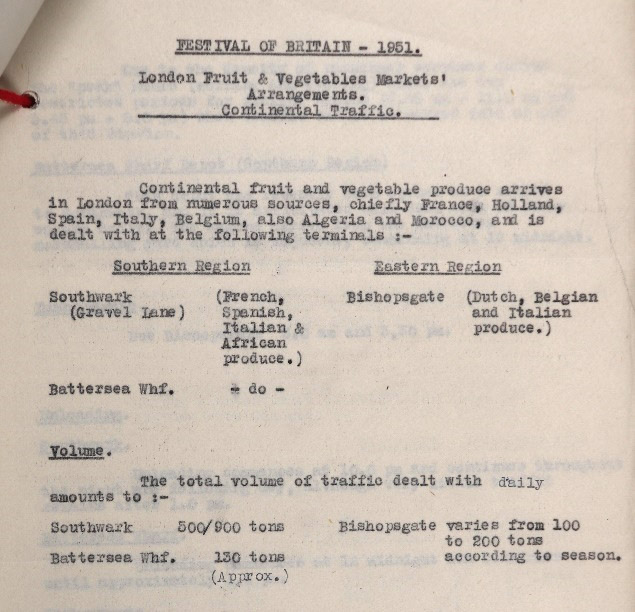

London’s fruit and vegetable markets were supplied by deliveries from across the UK and Europe which had to be transported by road and rail to the markets. The Ministry of Transport realised that when the Festival opened there was likely to be congestion on roads and railways, so in 1949 discussions began about the best way to ensure the fruit and vegetable markets weren’t disrupted.

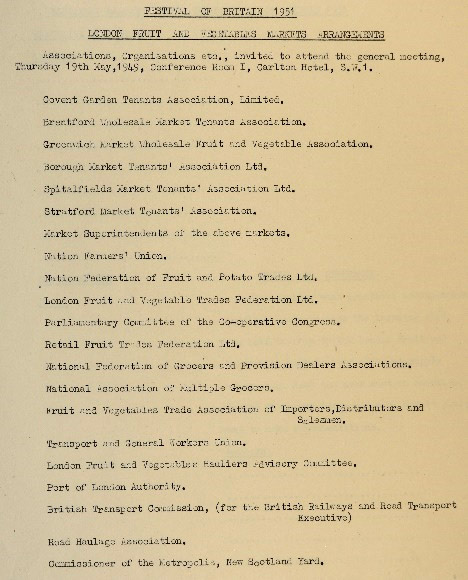

The Ministry decided to organise a meeting of interested parties including representatives of the various markets, Trade Unions and Associations, the Port of London Authority, the Metropolitan Police and members of the British Transport Commission’s Railway and Road Transport Executives[ref]The British Transport Commission (BTC) was set up after the war by the Attlee government to manage roads, railways and canals. The BTC had five Executives to operate the services: Docks and Inland Waterways, Hotels, London Transport, Railways and Road Transport.[/ref].

The British Transport Commission (BTC) wrote to the Ministry of Transport expressing frustration that such a large and cumbersome group had been called together. The BTC felt that they and their Railway and Road Transport Executives should have been consulted first because they already had oversight of all the issues that would be under consideration. It’s not clear from the file whether the Ministry hadn’t thought of this, or had a reason for deciding against it, but it certainly looks like a sledgehammer may have been constructed simply to crack a nut.

Following the initial meeting, a series of five sub-committees were formed to consider the best way to resolve particular issues. For example, the terms of reference for sub-committee number two were ‘to consider what practical arrangements should be made to deal with the Continental produce arriving at Railway Depots, in particular, those south of the river – in order to avoid deliveries to the London Fruit and Vegetables Markets during the hours between 9am and 11pm’[ref]AN 13/1579. British Transport Commission Festival of Britain Traffic arrangements.[/ref].

One suggestion to ease congestion was to ask the markets to open earlier than their usual 5.45am – but this was complicated by the fact that employees would struggle to get to work before normal public transport was operating. The Ministry of Transport approached the British Transport Commission to ask whether earlier trains and buses could be provided to facilitate this:

‘This matter has again been under consideration by the Executive Committee set up by the Ministry of Food to study the various aspects of the Covent Garden traffic problem. The Committee have recommended that the market shall be open for all purposes at 4.30am and have asked this Ministry to make further enquiries about transport arrangements for workers. The representative of the Transport and General Workers’ Union has enquired whether workers might be allowed to use the special trains run for London transport workers, such as the Becontree train, and whether special buses might be run as in the case of Fords.’[ref]ibid.[/ref]

As is often the way with archives, the file comes to an abrupt end without indicating what arrangements were eventually agreed. But even this snapshot illustrates the depth of preparations needed and how much more protracted they were without the advantages of email and spreadsheets!

Festival bus tour

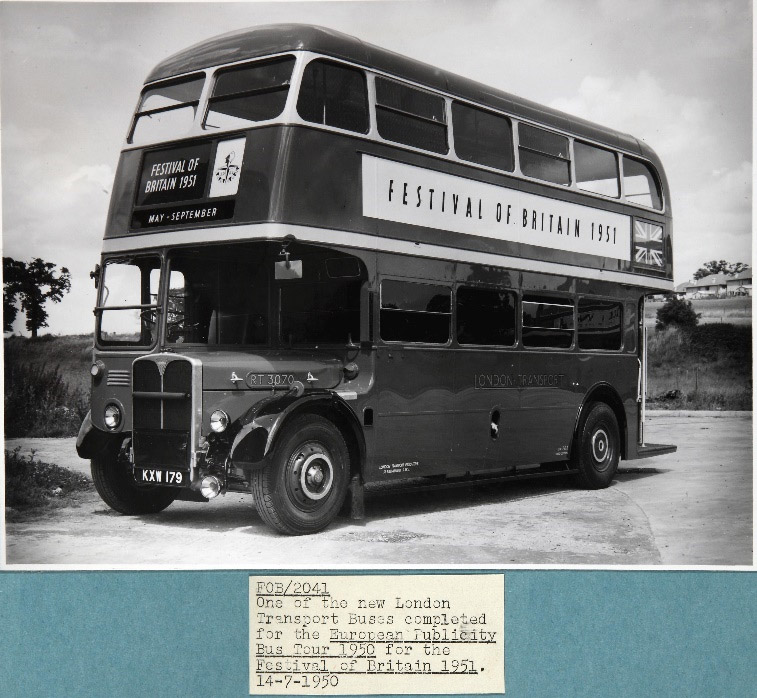

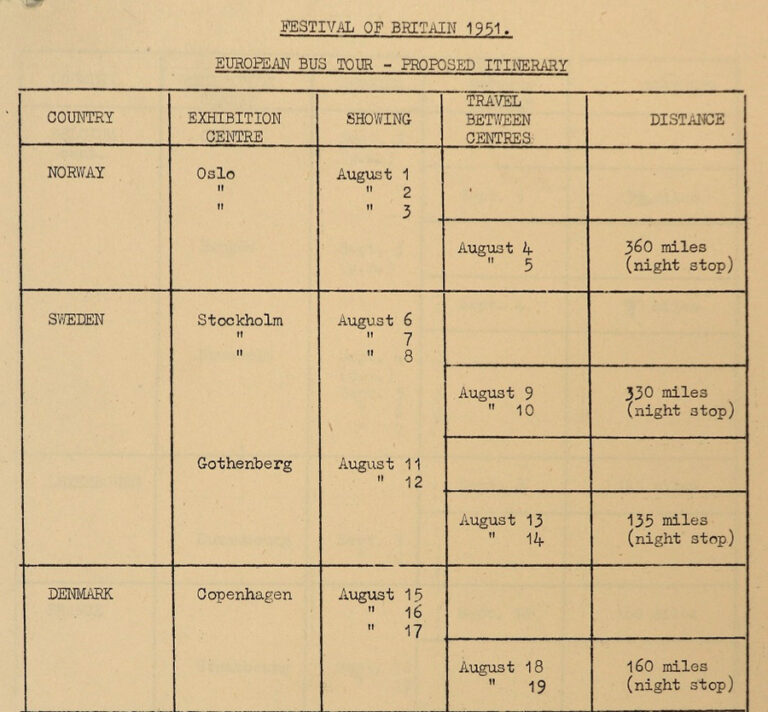

The Festival Office, which was the main organising body for the Festival of Britain, decided to send four London buses on a 4,000 mile tour of Western Europe and Scandinavia to ‘spread knowledge of the aims and objects of the festival and to publicise its programme’[ref]FO 953/660. Publicity arrangements for the Festival of Britain 1951: publicity bus tour of Europe.[/ref]. The buses were kitted out with exhibits and promotional material and gave free rides to visitors.

The idea conjures up visions of the Cliff Richard film ‘Summer Holiday’, but in reality, arranging the bus tour was a bit of a diplomatic minefield. The National Archives has Foreign Office files with correspondence about, among other things, post-war road conditions, exhibition material translations, and decisions about which dignitaries should be invited to official openings.

Plans for the Swedish leg of the tour were put in doubt when the British Embassy in Stockholm pointed out that ‘August is, after July, the worst month for such an exhibition … Until nearly the end of that month every local inhabitant who can possibly get away is on holiday and the town is “taken over” by tourists, many of whom are English’[ref]ibid.[/ref].

The British Embassy in Stockholm also pointed out that the route suggested by the Swedish authorities took the buses under a viaduct that allowed just one inch clearance. As if that wasn’t bad enough, ‘bolted to the main cross-girders of the viaduct there are two pieces of angle-iron which reduce the head room by as much as two inches’. After close inspection of the viaduct, the eventual conclusion was that ‘in all the circumstances – the angle at which the bridge crosses the road, the slight camber of the road and its cobbled surface – one inch clearance is not enough margin for safety. The angle-irons would cut clean through the thin tops of the buses at the slightest touch’.[ref]ibid.[/ref]

The British Legation in Berne, Switzerland, also sent concerns about the tour plans to the Foreign Office, this time to do with the size of the buses. After consulting with the Swiss Automobile Club they wrote to say:

‘The Swiss will not allow any vehicle which exceeds the prescribed measurements of 4 metres in height and 2.4 metres in width to enter the country. Even if the tyres were to be deflated or removed, I doubt whether this drastic measure would effect the necessary reduction in height. As regards level crossings – the whole of Switzerland is honeycombed with them and it would be quite impossible to traverse the country without encountering at least a dozen.’ [ref]ibid.[/ref]

Another problem emerged as the exhibitions and promotional literature in the buses was translated into the relevant languages for the countries they’d be visiting. When a representative from the Norwegian Embassy was invited to come and check the texts for Norway, they weren’t particularly impressed:

‘Mrs Tennfjord found the texts already printed and in position, and when she pointed out to Mr Keiller that there were a number of important errors, and that the style generally was un-Norwegian, he asked her, in view of the shortage of time, to confine corrections to major, definite mistakes, and to overlook anything which, although perhaps not in good Norwegian, could nevertheless be understood by the general public, who would probably not be too critical. Mr Keiller admitted that in some cases, where a word appeared that was not Norwegian at all, he had altered the word used by the Norwegian translator, thinking he knew best, as he had “spent some time in Scandinavia, knew some Norwegian, Swedish and Danish, but had evidently confused a Swedish word with the Norwegian”!’[ref]FO 953/663. Publicity arrangements for the Festival of Britain 1951: publicity bus tour of Europe.[/ref]

Royal Festival Hall motif

The Royal Festival Hall is the only structure from the Festival of Britain that still stands, and papers in a Home Office file show how the London County Council had sought ideas for a name for the new venue. Howard Roberts, the Clerk of the Council, wrote to the Home Office to say:

‘In response to an enquiry made through the Private Secretary to H M The King regarding the naming of the Council’s concert hall which is at present in course of construction on the south bank of the River Thames, His Majesty has graciously suggested that the hall might be named “The Royal Festival Hall”.’[ref]HO 45/25934. Festival Hall: grant of title ‘Royal’ and associated crown motif.[/ref]

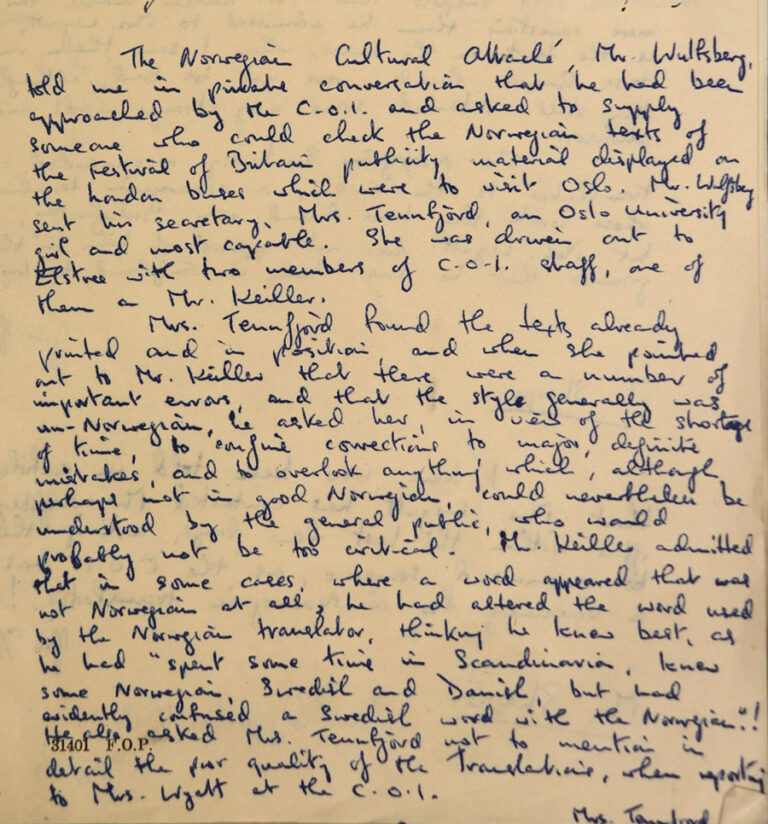

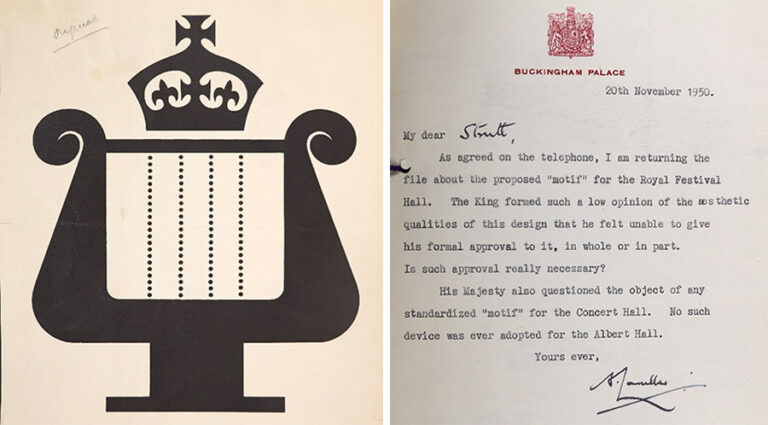

The council commissioned celebrated German graphic designer Frederick Henri Kay Henrion to design a motif for the hall. The design was submitted to the King for his approval, but unfortunately he was rather underwhelmed. Tommy Lascelles, the King’s Private Secretary, wrote back saying: ‘The King formed such a low opinion of the aesthetic qualities of this design that he felt unable to give his formal approval to it, in whole or in part. Is such approval really necessary?’.

After discussions with the designer, three alternative sketches were prepared and sent back to the King, along with the original design, and a letter explaining that the motif needed to be strong yet simple as it had to be capable of being reproduced on a very small scale such as on a programme. The accompanying letter went on to say:

‘the Royal Festival Hall in itself is an outstanding example of modern architecture; it is, indeed, a square modern structure on stilts, so the emblem is designed in a contemporary and modern idiom, representative of the Royal Festival Hall – the base of the lyre representing the stilts, and the general shape being square to correspond with the square auditorium of the Hall.’[ref]ibid.[/ref]

A further letter from Tommy Lascelles must have come as some relief to the council as he wrote to say ‘The King has no objection to design No 1, returned herewith, being adopted as a motif for the Royal Festival Hall’.[ref]ibid.[/ref]

Thankless tasks

After reading these and other ‘untold stories’ about the planning and organisation that went in to the Festival, I was struck by the enormity of the undertaking and the degree of coordination that was required across government. I’m sure none of the visitors to the Festival had any idea how much effort went in to making it all run smoothly.

Interesting as always and as a former graphic designer I was particularly interested to read of Henrion’s design, the King’s response and the designer’s rationale.

It does look rather unexciting when compared to Abram Games’ winning logo for the Festival.

But then again one was for the overall event and the other a building that would house some of the Festival’s events.

And I thought Brexit was complicated. Brilliant piece about the Buses and Bridges, still relevant today and buses are still losing their lids. Classic tale of closing the stable door with reference to the universal printed slogans in the wrong language already affixed to the buses. I was also a bit confused as to why Switzerland had so many level crossings.

And the poor old monarch must he really approve the logo ?

Ho Hum!