Today, as we write this blog, people across the world have been separated, in one form or another, from their loved ones. While we are socially distancing due to the Covid-19 pandemic, we are still finding ways to communicate with each other; we can comfort one another in times of difficulty, celebrate birthdays together and even socialise with friends through various different, often digital, mediums.

For us in 2020 there are dozens of ways to stay in contact, but this has not always been the case. The National Archives is home to an unknown amount of letters, some of which express deep sentiments of love, loss and longing. These letters not only allow us to appreciate how those in the past experienced love, but many of them can also give us insight into how couples remained closely connected while separated from one another.

These letters can only tell us so much, however, and it is with the help of archives, historians, and records experts that we are able to uncover the story of the people behind their words. This is what The National Archives does in the third series of our podcast, On the Record at The National Archives, which is all about love. In episode one, we used letters chosen from our exhibition, ‘With Love’, to look at stories of disappointed and forbidden love.

To coincide with the release of episode two, we wanted to reflect on other love stories within our collection where love survives divisions – whether that be due to prolonged separation, outside pressure, or tragedy.

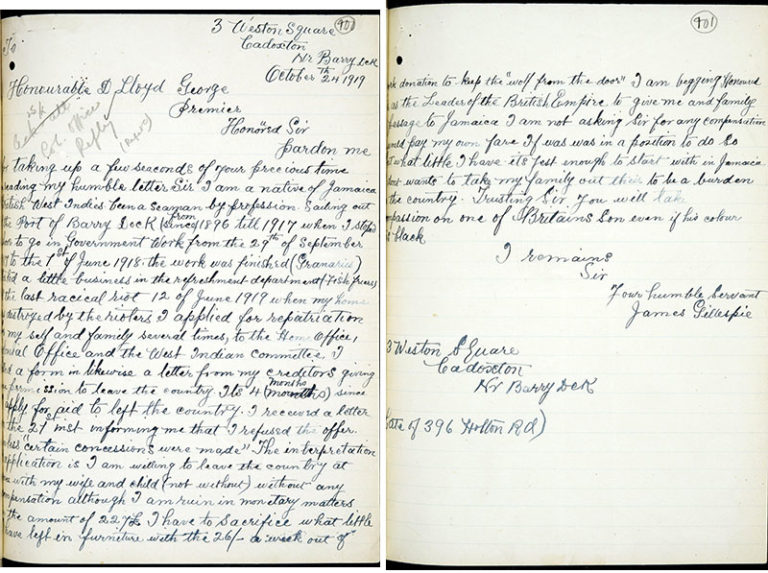

In this episode we hear the story of a Jamaican sailor named James Gillespie, who was forced to leave Wales in 1919 after the Race Riots. James had previously worked on steam ships and had sailed in and out of the port of Barry for almost 20 years before settling in the town. There, with his wife, he ran a fish and chip shop which was targeted and irreparably damaged during the riots.

Listen to the podcast here:

With his livelihood ruined, James wished to be repatriated to Jamaica and wrote a letter to Prime Minister, Lloyd George, asking for some financial help in order to make his move easier and ensure that he would be able to survive once he got there. This is crucial because James explicitly says that he will not leave without his wife and child. We read his letter as a love note of sorts; James is expressing his love for his family in that he cannot bear to be separated from them.

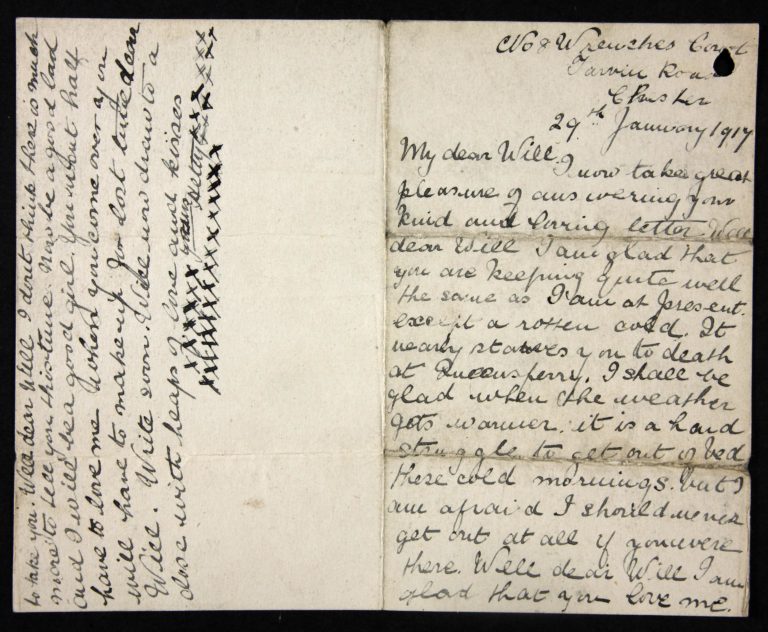

James and his generation were no strangers to the prospect of being parted from their loved ones. Other love letters in our collection show the impact of the First World War on young love. Within the service record of a young man named William we find a series of letters and cards from his sweetheart, Hetty. The young couple, like thousands of others, were separated by distance and conflict while William served on the Western Front. Only Hetty’s letters survive, and they are a vivid record of the love between the couple and a stark reminder that the war, and their separation, lasted longer than those caught up in it ever expected. In her letter she writes:

‘You won’t half have to love me when you come over again’

Sadly, William died of wounds in February 1918 and we do not know whether Hetty found another love.

Hetty’s letters are also a great example of the surprisingly romantic records that can be found within our collection. They are particularly unusual though, as personal possessions were generally returned to the families of soldiers who died in battle. However, we know that the only family William had was an uncle by marriage, who in another letter asked that William’s medals and awards, along with his personal effects, be presented to the King in memory of him.

It is likely they were returned to his regiment, the Household Battalion, to be destroyed. Instead these letters survived as a rare record of the loving relationship of a young couple unhappily separated by war.

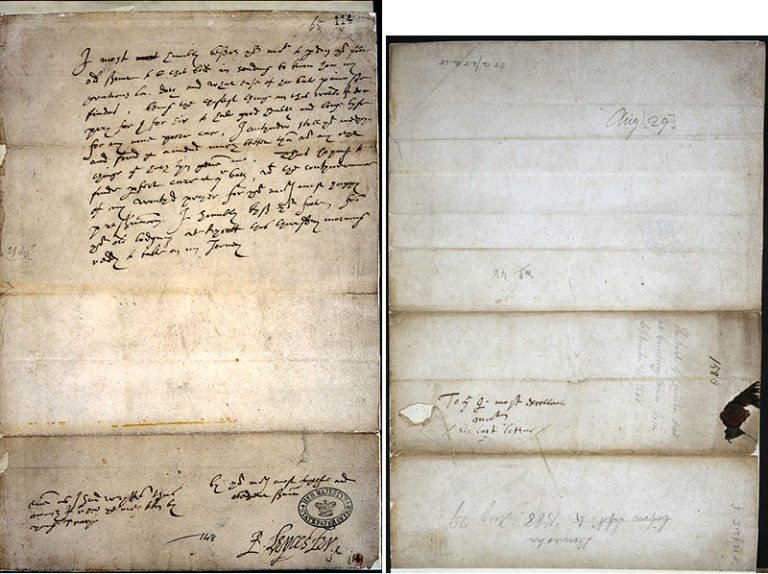

Lovers separated by war, work or duty are not a modern phenomenon. Reflecting back over 300 years we find the well-told tale of a queen and her love for one of her subjects. Friends since childhood, Elizabeth I and Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, remained close companions throughout their lives. Fondly referred to as her ‘eyes’ in court, he was widely known to be one of her favourites. He was her confidant and friend, and he provided her with considerable support throughout her reign. Although rumours circulated that they were embroiled in a passionate love affair, these rumours were unconfirmed and the two never married.

While projecting the image of a virtuous and chaste queen, Elizabeth was unable to marry, as this would have undermined her political prowess and authority as a divine ruler. In this episode, we hear why this seemingly trivial letter from Robert to Elizabeth is thought to hold so much importance.

Although his letter speaks of everyday woes, it is significant as it is believed that Elizabeth kept this letter, the last letter he sent to her before his death, by her bedside for the 15 years she outlived him. With evidence of this being true lost to the archive, historians and researchers alike will always wonder whether this is a story of a courtly love affair or an echo of rumours past.

‘I left my heart within your sweet breast at my departing from you, and am united there with you in spite of this tedious intermission of my joy, which makes me live here like a man without a soul’

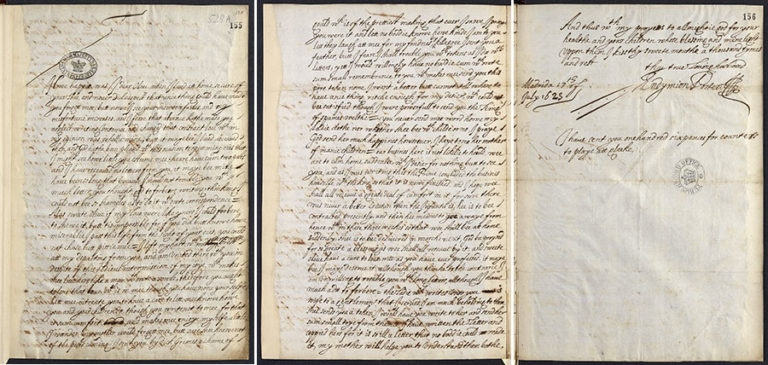

Endymion Porter wrote these frustrated words to his beloved wife, Olive, in 1623 while in Madrid accompanying the future Charles I on a mission to the Spanish royal court.

As Endymion worked for the royal household, he was often parted from Olive, resulting in him writing to her regularly. Roughly 30 letters between the pair survive in the repositories of The National Archives, giving us valuable insight into their long-distance marriage.

Clearly a passionate and often jealous relationship, this letter shows a man desperate to hear from his love, writing ‘I fear that absence hath made you neglect writing to me, and changed that constant love which in my opinion was wholly mine’. Despite his accusations that Olive had forgotten him, he had previously received at least six letters from her in the four months he had been in Spain.

Endymion and Olive’s letters remind us of the trauma couples experience when forcibly parted. Without the technology we have today, writers could wait weeks, sometimes months, to have their declarations of love reciprocated. For this couple, great suffering brought great reward – Endymion returned to England with Charles no more than two months after this letter was written where he was reunited with his wife.

On the Record at The National Archives: Series three available now

Episodes one and two are now available on the Archives Media Player and on podcast listening apps. The third and final instalment for this series will be available from 21 May, when we’re going to share two letters on the theme of sacrifices made for love. One tells of a king giving up his throne to be with the woman he loves; the other about an elderly pauper giving up shelter and security to stay with his wife at the end of their lives.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on series one which focused on espionage, uncovering the true stories of famous spies, and series two which looked at protest – from the medieval Peasants’ Revolt to black power in the courtroom.

‘With Love’ online exhibition

Uncover stories of heartbreak, passion and disappointment through love letters spanning 500 years in our online exhibition.