Florence Nightingale, famous for her work as a nurse and social reformer, was born 200 years ago on 12 May 1820. This is the first of a two-part blog exploring the records at The National Archives that shine a light on her incredible life; from birth through to her nursing endeavours in the Crimea War and beyond.

During the Crimean War (1854-1856) Nightingale improved the sanitary conditions of the British military hospital in Scutari, showing through data collection and analysis that these efforts helped to reduce the death toll. Returning home a hero, she spent the rest of her life driving reforms in nursing and hospital design, writing books, and corresponding on public health, theology and politics.

Florence’s early life

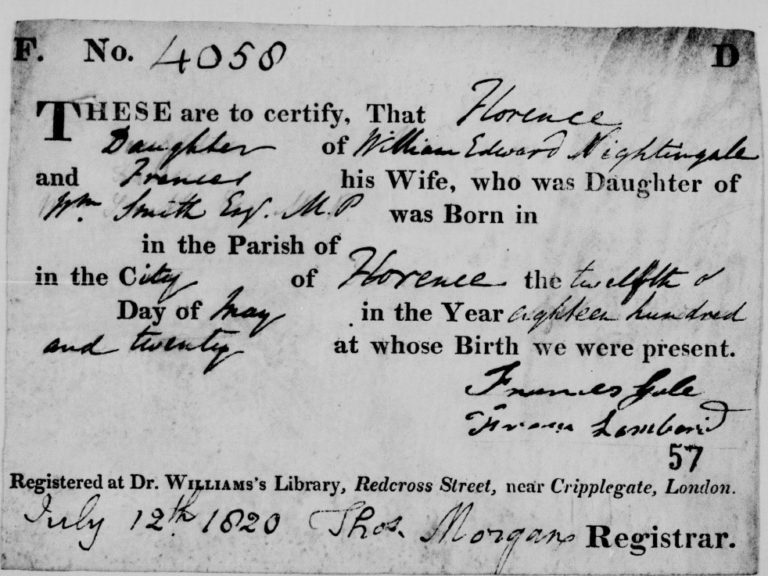

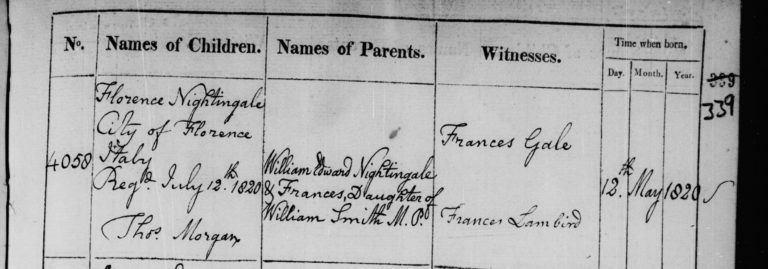

Born to wealthy parents in Florence, Italy, Nightingale was bought up following the Unitarian religion on her family’s estates in Hampshire and Derbyshire. Florence’s birth certificate can be found among The National Archives’ non-conformist records in RG 5, available online (£)[ref]RG 5/83. Florence Nightingale’s birth certificate from a collection of original parchment and paper certificates from which the entries in the registers of births from the Presbyterian, Independent and Baptist registry at Dr Williams’ Library were compiled.[/ref].

Nightingale was born during the period of the first industrial revolution, a time when the textile industry and transportation links were developing. It was from industry that her father’s wealth derived. An industrialist and lead mine owner, Peter Nightingale left the bulk of his estate to his great nephew, William Edward Shore, who was required to:

‘take upon himself…the Sirname of Nightingale and by the said Sirname of Nightingale only and no other from thenceforth for ever thereafter continue to name stile and write himself…in all Deeds Instruments and Writings”[ref]PROB 11/1399/3. Will of Peter Nightingale of Matlock, Derbyshire.[/ref].

The will of Peter Nightingale can be downloaded from the record series PROB 11 in Discovery, The National Archives’ catalogue. The announcement of Florence’s father’s name change under Royal Warrant can also be found in the London Gazette[ref]The London Gazette, 25 February 1815, p. 338.[/ref].

Census records highlight the family’s wealth. In 1851 the Nightingale household included a ladies maid, a footman, two waiters, two housemaids, three laundry maids, and a cook[ref]HO 107/1485. 1851 census, Registration District: 6 St James Westminster. Available to download from Ancestry.co.uk.[/ref]. As a result of the family’s high social standing, Nightingale had a broad education and travelled widely. Her interest in nursing came at a young age and, influenced by her religious convictions, she visited infirmaries at home and abroad. In this period, nursing as a profession was not considered a respectable vocation for the upper-classes. Despite provocations from her family, in 1851 she trained as a sick nurse in Germany. Two years later she secured the position of Superintendent of a hospital in Harley Street, London and nursed cholera patients during the London epidemic.

Florence ‘Called Up’

The Crimean War, a military conflict between Russia on one side and Britain, France, Turkey and Sardinia on the other, was fought over a period of 18 months between 1853 and 1855. New technologies, like the steam-powered rotary press and railways, made print cheaper and easier to distribute than ever before, allowing for the conditions of the war to be reported to wider audiences.

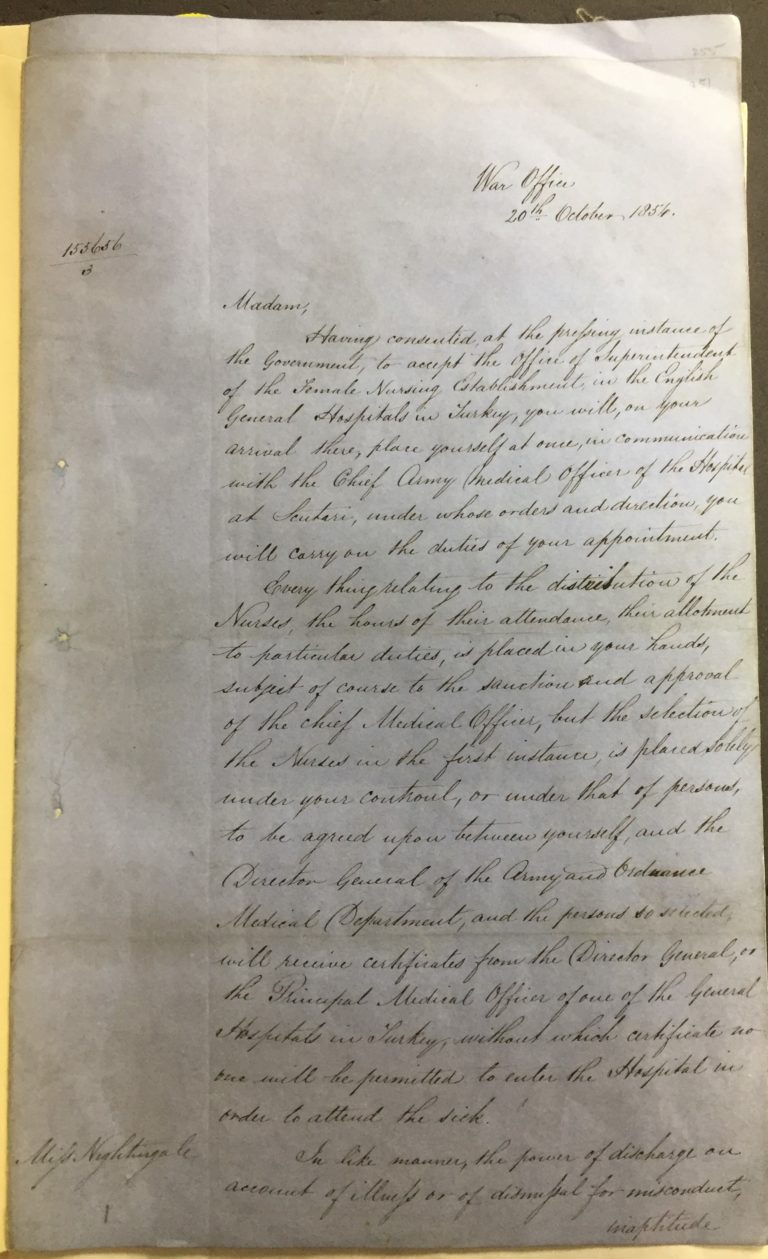

Following some scathing reports about the state of hospitals and lack of nurses in the East, the Secretary of State for War, Sidney Herbert, appointed 34-year-old Florence Nightingale to take a party of 38 women over to the military hospital in Scutari, including professional nurses, upper-class ladies, and woman from religious nursing orders. A copy of a letter from Herbert is found in War Office correspondence files (WO 43) outlining Nightingale’s authority: ‘every thing relating to the distribution of the Nurses, the hours of their attendance, their allotment to particular duties’ was placed in her hands ‘subject of course to the sanction and approval of the Chief Medical Officer'[ref]WO 43/963. Nurses in the Crimea. Correspondence and memoranda of Florence Nightingale, Sidney Herbert et al. Letter from Sidney Herbert to Florence Nightingale, 20 October 1854.[/ref].

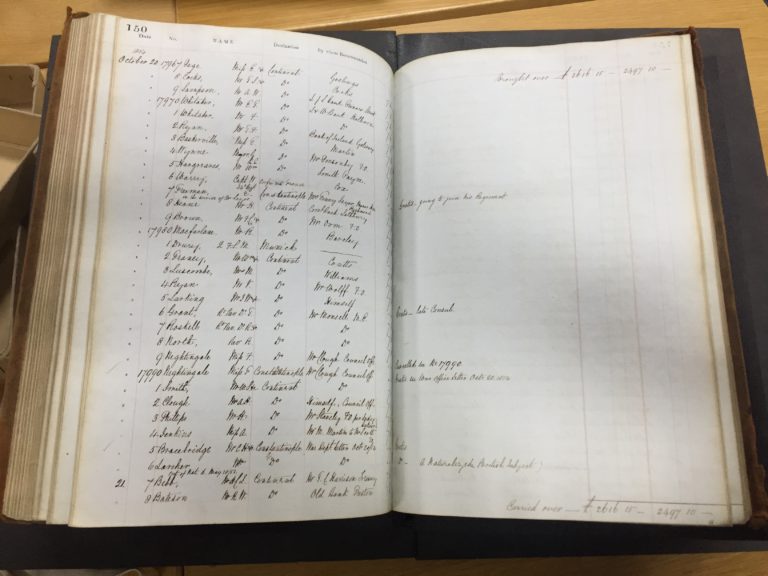

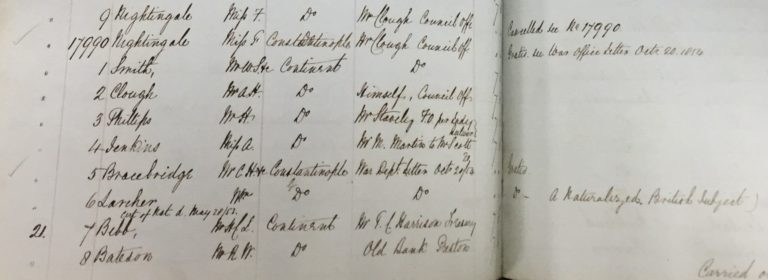

With the support of the War Office, Nightingale left England on 21 October 1854 to travel to the war zone. Evidence of the journey can be found in the passport registers held at The National Archives. The register, dated 20 October, shows that ‘Miss F Nightingale’ (passport number 17990) was given “gratis” passage to Constantinople[ref]FO 610/8. Entry book of passports issued, July 1854–March 1855.[/ref]. The government covered the nurse’s cost of passage, and the ongoing cost of house rent and subsistence as well as up to two months sick leave[ref]WO 43/963. Nurses in the Crimea. Correspondence and memoranda of Florence Nightingale, Sidney Herbert et al. ‘Rules and Regulations for the Nurses Attached to the Military Hospitals in the East’.[/ref].

Florence was off to war but, as will be explored in the next blog, she would find her task difficult and her authority challenged, as she and the nurses under her command worked to save lives.

Use our research guides to find out how to search census, passport and probate records in The National Archives collections.

Very interesting would like to see more about her

It’s interesting to read the history of Florence. Especially, as I have the same surname. I also have worked with social reform and am a practising Charismatic Christian.

I had never realised that Florence Nightingale came from a wealthy family.

This, of course, made it easier for her to pursue nursing and to travel to

Constantinople, despite initial objections from her family.

I am so glad you are making this information available.

It is absolutely right that the work of nurses and midwifes be celebrated this year,

2020, especially in view of their indefatigable work with Coronavirus patients.

i thank you for the contribution, however the contribution ended with the Crimean War. I know that she initiated a nurse training college for workhouse nurses later. What else other than nurse in Crimea was she involved in?

I enjoyed this immensely as a retired nurse my training began with nursing history. I must say a lot of what I found here wasn’t in my nursing history class. This encourages me to read further about this wonderful woman in history.

Extremely interesting, and her work was the basis for good hygiene and nursing.

Thank you.

Dave Sieff, Johannesburg, South Africa

Excellent information to discover how Nightingale came to be so famous.

This is really interesting how Florence had such difficulties with the Doctor who wanted to be in charge of everything, and was not prepared to listen at all to anyone especially a woman who may have different ideas, especially if they were working. Not much has changed in some areas today. There are still people not only men who want total control over what does and does not happen in health and the wider community areas where health is the main area we need to be aware of. Living conditions for some have never changed and of course education is the best thing but it is still difficult to break down the social and family ways of doing things.

Great blog. I’m working as a nurse with the military and currently researching the nursing and medical care at Fort George Inverness. I was interested to discover that when the soldiers returned to the fort having been out to the Crimean war the layout of the small hospital in the barracks was changed to suit the recommendations made by Florence Nightingale

Our interest in the Nightingale family rose because we have been trying to prove that ancestors were their employees. Thomas Tristram born in Madley, not far from the house they rented in Presteigne, married Anne Blyton born near Lea Hurst, married at East Wellow church 1926, a rear after Embley Park was purchased, later records show Thomas worked as a man servant and a cab driver for a large estate in Derbyshire . Do any archives exist on the household accounts of these properties?

Their son Blyton Valantine Tristram was woundedvthe the Crimean war so possibly treated by Florence.

I have a book. Surgical Experiences.

Clinical lectures by Samuel Solly.presented” to miss Florence nightingale” but I can’t quite decipher the name of the person who sent it.

I found it in a shed in west Wellow.