This is the last in our series of blogs marking the release of the film ‘Peterloo’. You can find our previous posts here:

This time we look at the state response on 16 August 1819, and the impact this had on central policy for the rest of the century.

The means of maintaining law and order in Britain in 1819 bore little resemblance to what was in place after the 1850s, let alone to what we see today. The supposed English commitment to localism and liberty meant that professional police forces were unwanted: they represented an extra financial burden, as well as the threat of ceding power from the provinces to central government. The prospect of a national force was considered inherently un-English and was viewed with suspicion, especially as it might provide a means of enforcing unpopular laws on the people.

As a result, centuries-old methods continued to keep favour among those in authority. In towns, this amounted to small numbers of constables or watchmen, with limited jurisdictions, supported by presiding magistrates. In rural districts things were even less developed, with vast swathes of the countryside formally unpoliced.

Beyond this limited capacity, support in times of emergency came from an ad hoc, largely reactionary system. Magistrates could and did swear in local volunteers as temporary Special Constables at the first promise of disorder. However, more often it was the army – in amateur and professional form – that stepped in to aid the civil power.

The reliance of the magistracy on military force was a well-established phenomenon, although the nature of those who turned out in its support had changed dramatically during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. This period saw outbursts of loyalism as well as discontent; one outlet for the former was a raft of new, amateur military movements. Of particular significance was the Yeomanry Cavalry, a voluntary force raised in 1794 under a unique statute. Unlike its contemporaries, this was the only force that could be mobilised in the event of domestic insurrection as well as invasion.

The Yeomanry frequently played a part in the control of riots during and after the wars with France. Usually this was because magistrates did not have immediate access to professional soldiers before the fledgling rail network opened up the country. In fact, this issue of the availability of manpower – whether it be to the army or emerging police forces following the 1839 County Police Act – was one of the main reasons the Yeomanry was maintained well beyond the peace of 1815. Drawn from the populations it would be asked to control, it met the needs of the magistracy by being both cheap and local. It was also seen as inherently reliable due to its largely middle-class composition.

Although the Home Office communicated constantly with a network of magistrates in the provinces, it was typically distant from events on the ground. As a result, it vested power and authority in those magistrates, and their responsibility was to maintain law and order locally. Professional and amateur military forces became essential tools to these officials when events escalated beyond the reading of the Riot Act – although we should not assume this always led to violence. To give some idea of just the Yeomanry’s importance in this role, while regiments in 22 counties spent a total of 42 days on duty in aid of the civil power over the whole of 1819, there was only one Peterloo.[ref]House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, Paper no: 273, Session: 1828[/ref]

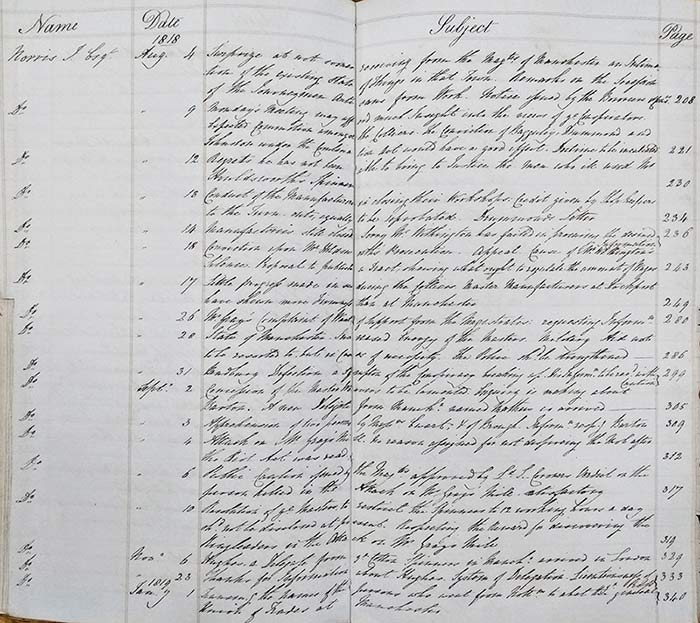

Index to outgoing correspondence from the Home Office, showing the frequent communications with regional magistrates (in this case James Norris, a stipendiary magistrate in Manchester). HO 79/3. Home Office: Private and Secret Entry Book

From this perspective, the course of events on 16 August is perhaps less surprising – even if the violence of the authorities still defies understanding. Alongside a sizeable body of special constables, military forces on the ground in Manchester included the Cheshire Yeomanry, the 15th Hussars, a detachment of the 88th Foot and the 31st Foot, two pieces of artillery and the infamous Manchester and Salford Yeomanry – a comparatively new and inexperienced unit. Once initial efforts by constables to reach Hunt had failed, the panicking magistrates called on the support of the military. It just so happened that a portion of the Manchester and Salford corps was closest and arrived first – and it was asked to force its way to the hustings.

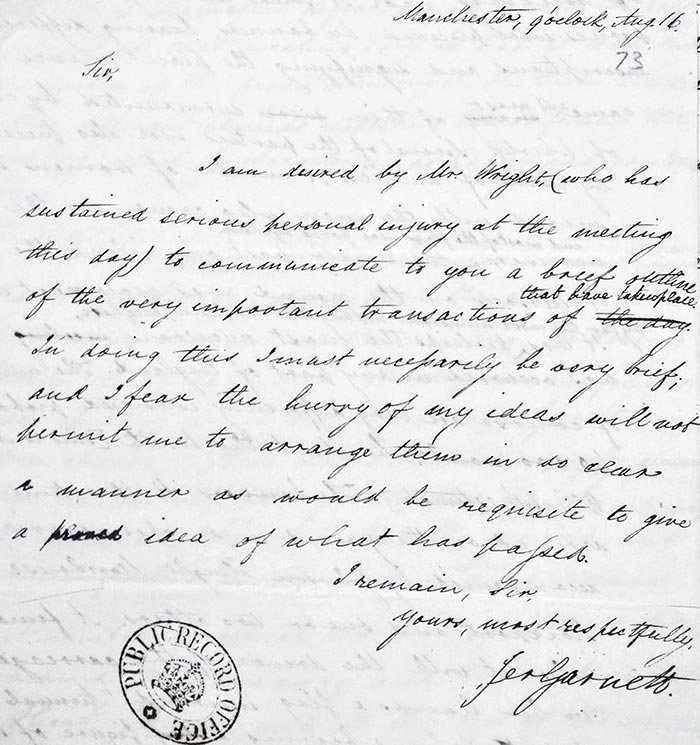

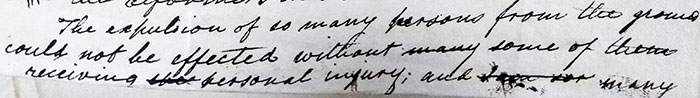

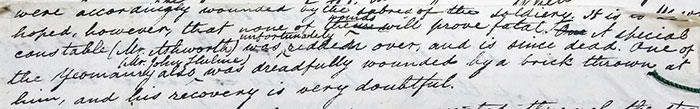

An account of events by Jeremiah Garnett, a journalist with Wheeler’s Manchester Chronicle. Garnett had been on the hustings with Hunt and forwarded this hastily written account to the Home Office at 21:00 on 16 August.

Lacking training and discipline, and committed to a task beyond their capabilities, these men were quickly swamped by the huge and (understandably) uncooperative crowd. As they thoughtlessly struck out with their sabres to free themselves (apparently using the edges of their weapons rather than the ‘flats’), the panic-stricken magistrates assumed they were under attack: they ordered the meeting to be dispersed by the remaining cavalry.

It was most likely from this point that the bulk of the deaths and injuries occurred – at least some at the hands of the 15th Hussars and Cheshire Yeomanry, as they pushed the crowd of 60,000 people through the narrow exits of the square, some of which were blocked by infantry.

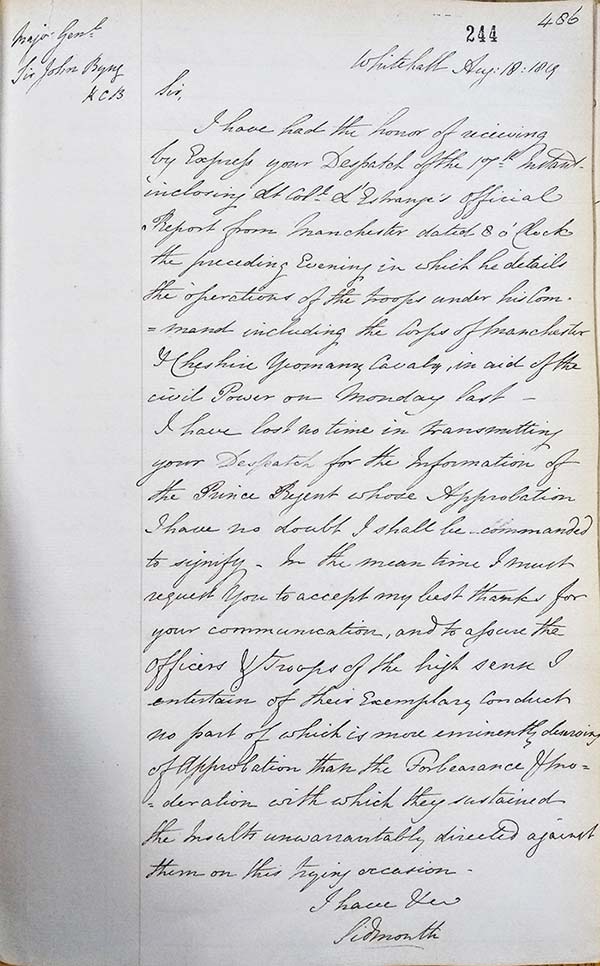

Lord Sidmouth’s letter of thanks for Lt-Col L’Estrange’s report of events and praising the ‘forbearance and moderation’ of the soldiers at Manchester. HO 41/4. Letter from Lord Sidmouth, Home Secretary, to Maj-Gen Sir John Byng, General Officer Commanding Eastern District.

Although this had been a peaceful meeting, the vast crowd could not be policed by the standing authorities or those sworn in as Special Constables to support them if the occasion demanded it. This meant that the presence of the armed forces was not only predictable, but was considered best practice. So, in their historical context – a critical caveat – the events that followed were not offensive because the state had used armed violence against its citizens. Instead, they were offensive because the state had used violence without justification.

The public outcry was widespread: regional meetings of support were held as far afield as Lewes in Sussex and Paisley in Scotland.[ref]Morning Chronicle, 9 October 1819; and Leeds Mercury, 8 September 1819[/ref] Although a court had effectively justified the conduct of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, even the authorities quietly condemned its actions. Major-General Sir John Byng, General Officer Commanding Eastern District, reassured Lieutenant-Colonel Townshend of the Cheshire Yeomanry that the Manchester corps ‘get all the blame from the Whigs’. [ref]Leary, F, ‘The Earl of Chester’s Regiment of Yeomanry Cavalry — its Formation and Services, 1797–1897’ (Ballantyne, Edinburgh, 1898), p82.[/ref]

However, central government was haunted by the prospect of revolution and saw the Manchester meeting as the beginnings of wider agitation. Lord Liverpool’s administration not only oversaw the introduction of the Six Acts mentioned in the first blog, it also increased defence spending dramatically to meet a predicted rise in violent protest. Although the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry was quietly wound up in 1824, by 1821 the overall spend on the whole Yeomanry force had increased by 75%. [ref]House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, Paper no: 67, Session: 1834[/ref] The obvious alternative – investing in professional police forces – would not really gain ground until the County and Borough Police Act of 1856 forced the creation of county constabularies.

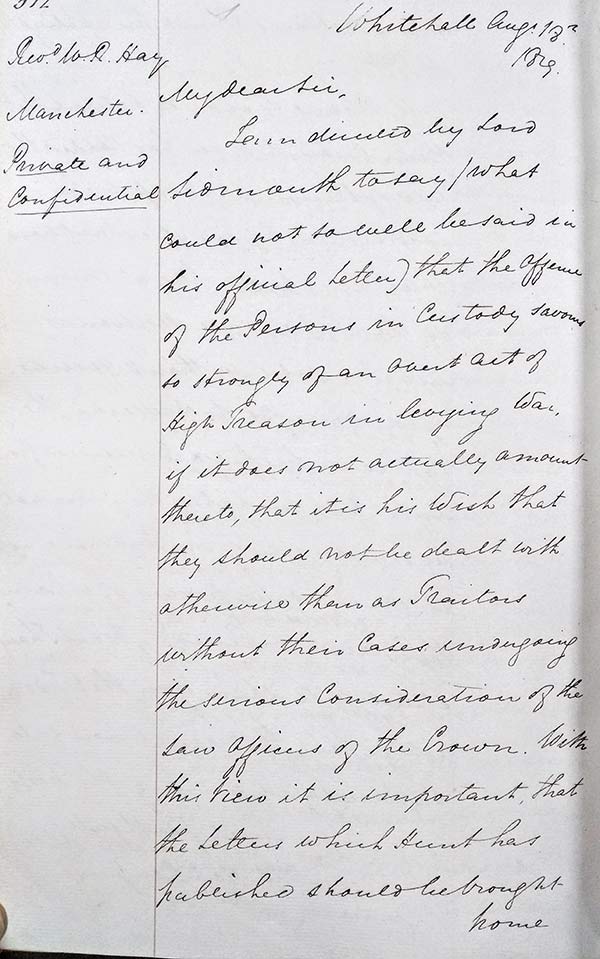

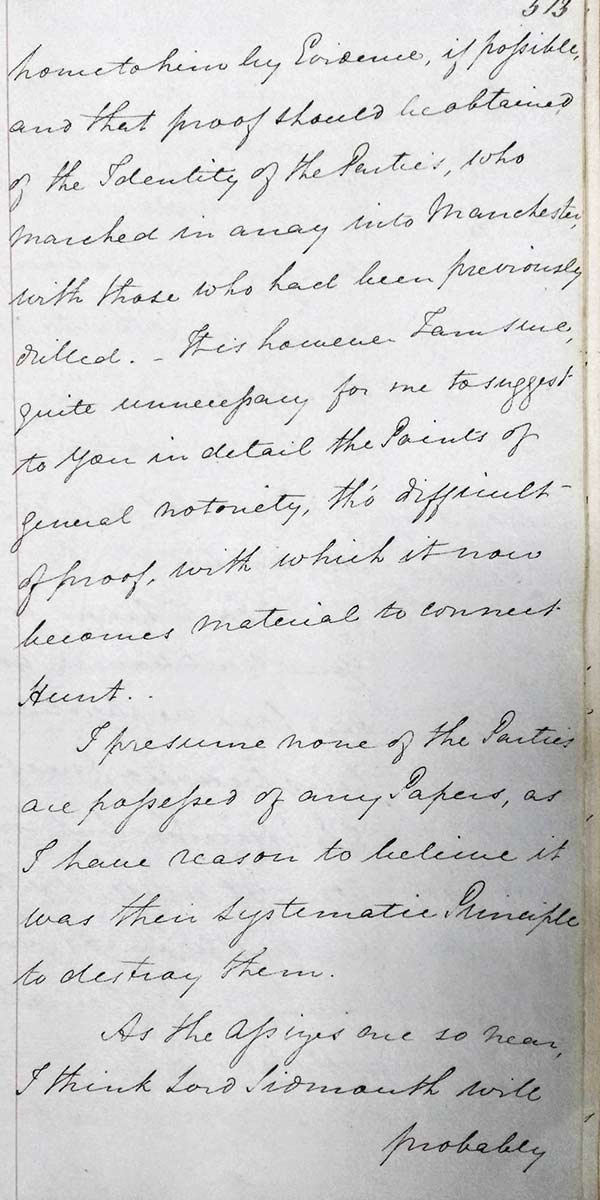

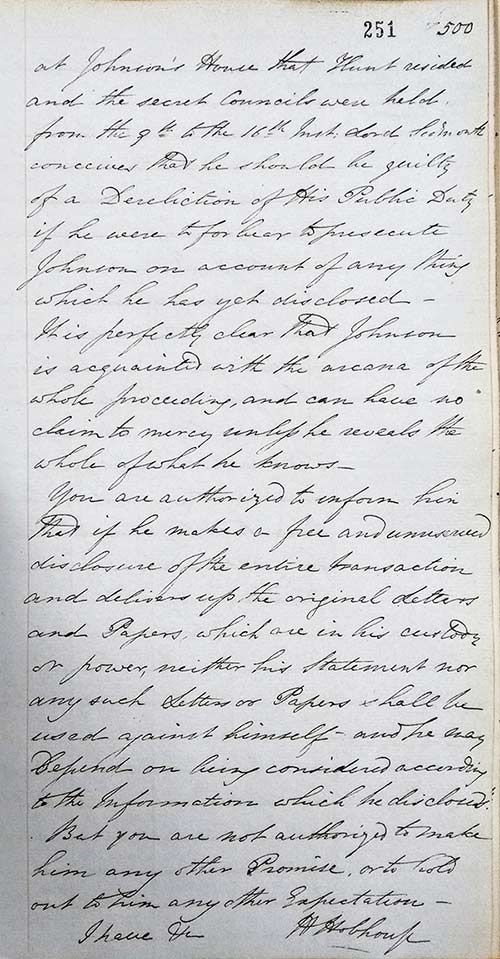

Letter response to the Rev William Hay, one of the magistrates on the ground at Peterloo. In it Henry Hobhouse recounts Sidmout’s wish that the men in custody ‘…should not be dealt with otherwise than as traitors without their cases undergoing the serious consideration of the law offices of the Crown’. HO 79/3. Home Office: Private and Secret Entry Book.

Despite their portrayal in the liberal and radical press, it is extremely unlikely that the magistrates, armed forces or the Home Office intended to do harm that day in Manchester. There is little doubt, however, that their decision making and incompetence brought about that result.

Peterloo did not necessarily hasten the progress the reformers were calling for, but it did have an enduring legacy in politics and in the way in which the authorities interacted with protest. Although the state readied itself for confrontation – and there were plenty more bloody clashes in the coming decades – none would demonstrate the same level of one-sided violence.

Some years later (1831), a riot occurred in Nottingham over the same cause: electoral reform (see https://parallax-viewpoint.blogspot.com/2016/10/where-is-nottingham-castle.html). The military were called in then, too, and people were fearful that a repeat of “Peterloo” would occur.