Florence Nightingale, famous for her work as a nurse and social reformer, was born 200 years ago on 12 May 1820. This is the second of a two-part blog exploring the records at The National Archives that shine a light on her incredible life. In part one we saw records relating to her early life up to when she left England to travel East, towards war, suffering, and life-long fame.

Florence in the Crimea

Arriving at the Barrack Hospital in Scutari on 4 November, Florence Nightingale and her party of nurses, nuns and ladies were met with wounded and sick soldiers being cared for on insufficient diets, many inflicted with scurvy. It was found that soldiers were succumbing to infection due to their unsanitary, overcrowded surroundings rather than enemy action[ref]WO 32/7580. Proceedings and Report of Sanitary Commission on hospitals in Crimea and at Constantinople.[/ref].

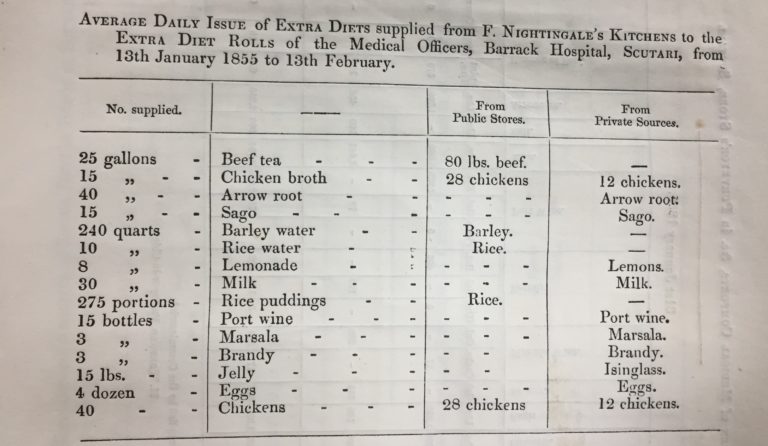

Nightingale set about improving the living conditions of the soldiers; frustrated with bureaucracy, she sent for her own supplies and equipment, butting heads with Dr John Hall, the official medical officer[ref]WO 43/950 includes correspondence from Dr John Hall concerning the reorganisation of the purveyor’s department. The purveyors were responsible for supplying medical equipment and food.[/ref]. It was noted in the ‘Report upon the state of the hospitals of the British army in the Crimea and Scutari’, written after the war, that ‘shortly after her arrival at Scutari’ Nightingale ‘commenced to supply the hospital with articles of furniture, clothing, and medical comforts. Her store, it will be seen, was supplied partly from the public, but chiefly from private sources…'[ref]WO 33/1. Report upon the state of the hospitals of the British army in the Crimea and Scutari, p. 33.[/ref].

Evidence of the conflict between Hall and Nightingale can be found in some of Nightingale’s correspondence held at the archives. Concerning the payment of two nurses who turned up unannounced, Nightingale ‘humbly’ begged the War Office ‘to give the necessary instructions to the Inspector General of Hospitals, Dr Hall, in accordance with those previously given to myself, to the effect that all requisitions and arrangements relative to the nurses for the Crimea & Scutari hospitals should pass through my hands'[ref]WO 43/963. Correspondence. Letter to Benjamin Hawes, Secretary of the War Office from Florence Nightingale, Scutari, 7 January 1856.[/ref].

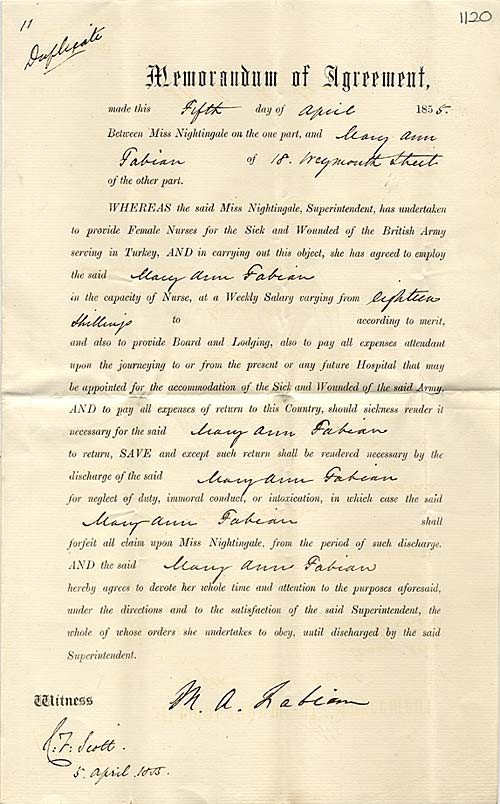

In a letter to the Secretary of the War Office in May 1855, Nightingale used her authority to caution about the recruitment of unsuitable women, remarking that women ‘living closely packed in narrow quarters under new discipline & in a barrack’ and ‘whose tempers & habits are unknown present great obstacles to management’. She urged that ‘those who send them should well consider what are the circumstances and what the cost and hardships of sending women home who may not suit the work and what the consequent result of working with bad tools'[ref]Ibid. 1 May 1855.[/ref].

Nurses of the Crimea War

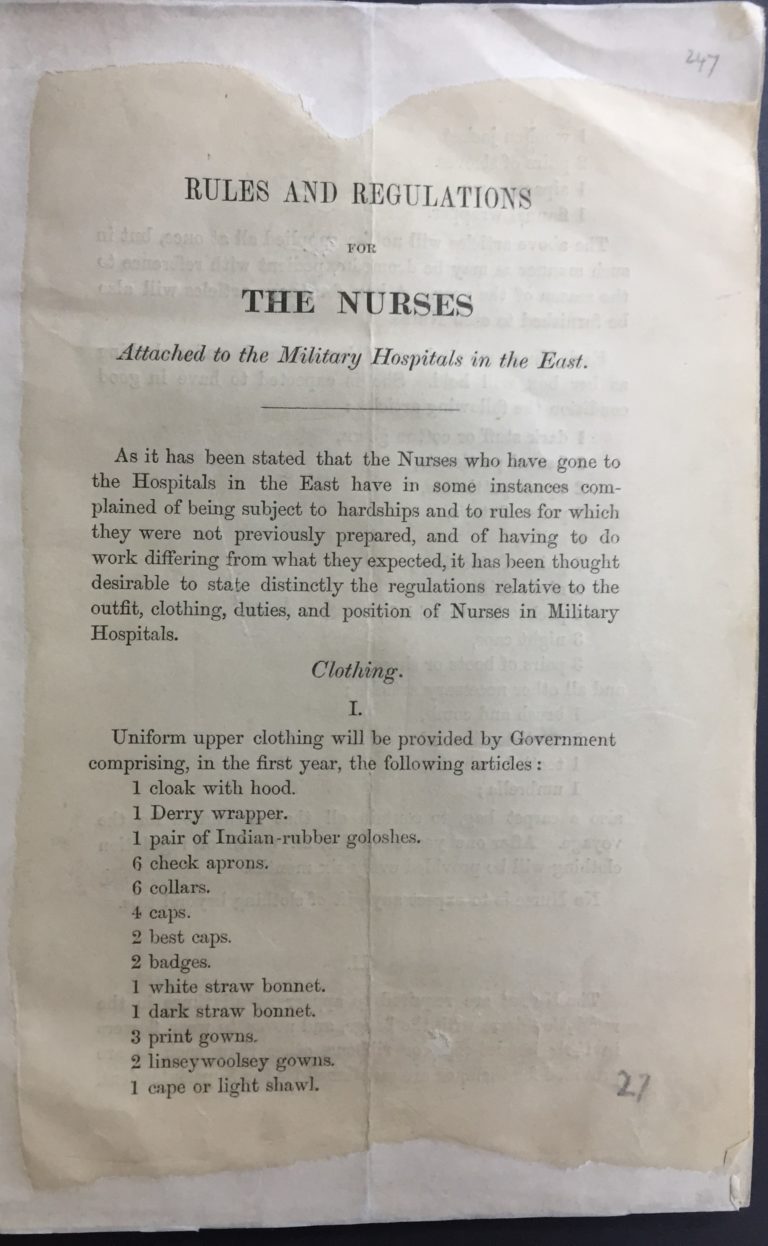

Carrying out medical care for soldiers on the front was hard work. The nurses’ duties consisted of:

‘in surgical cases, in washing, and preparing for the morning visits of the medical officer, such wounds as they are directed by that officer to treat in this way; to attend upon him in dressing the wounds; and to receive, and take to Miss Nightingale, his directions as to diet, drink, and medical comforts. In surgical cases, a corridor and two wards are generally assigned to four nurses. In medical cases, their duties consist in dressing bed-sores, seeing that the food of the patients is properly cooked and properly administered, and that cleanliness, both of the wards and of the person, is attended to'[ref]WO 33/1. Report upon the state of the hospitals of the British army in the Crimea and Scutari, p. 33.[/ref].

To prepare new recruits for work in the Crimea, a four-page booklet, ‘Rules and Regulations for the Nurses Attached to the Military Hospitals in the East’, was issued, outlining the uniform provided by the government, the clothes to bring, and the duties of the nurse.

Despite the difficult conditions, the War Office was inundated with letters from women offering to enlist as nurses, probably due to the conflict’s media coverage. Many of these testimonials survive today in The National Archive’s collection, in the record series WO 25/264.

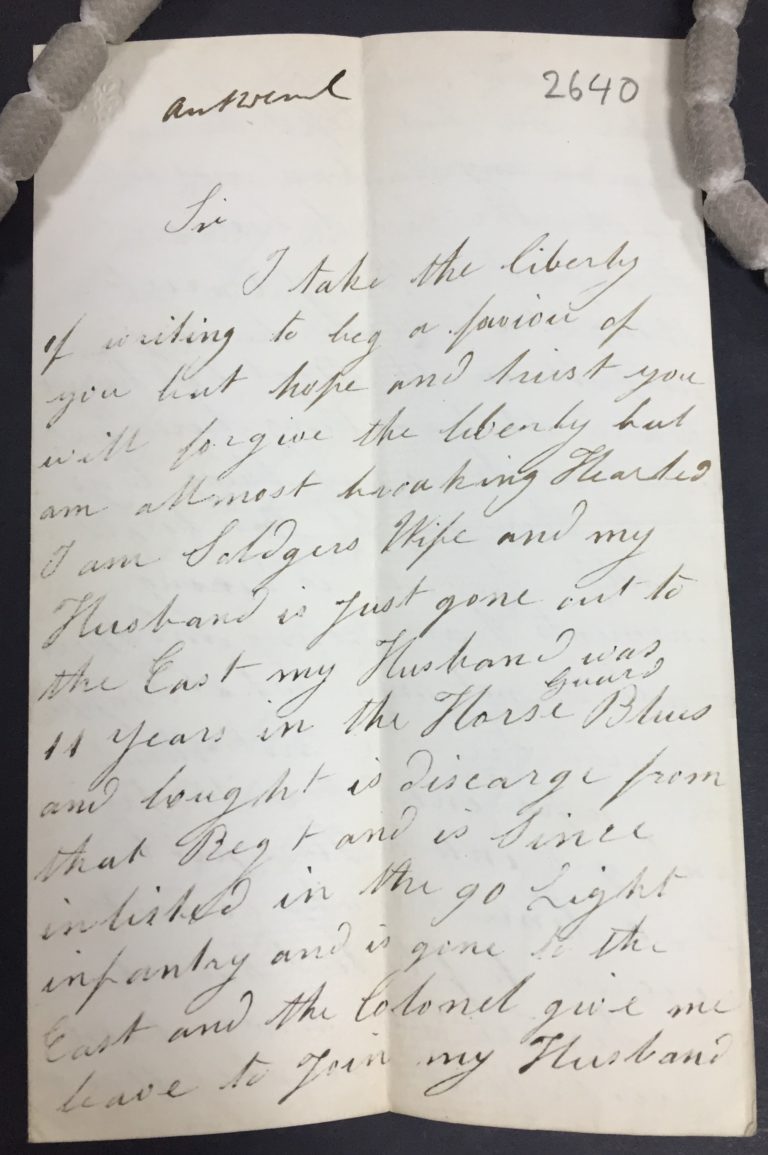

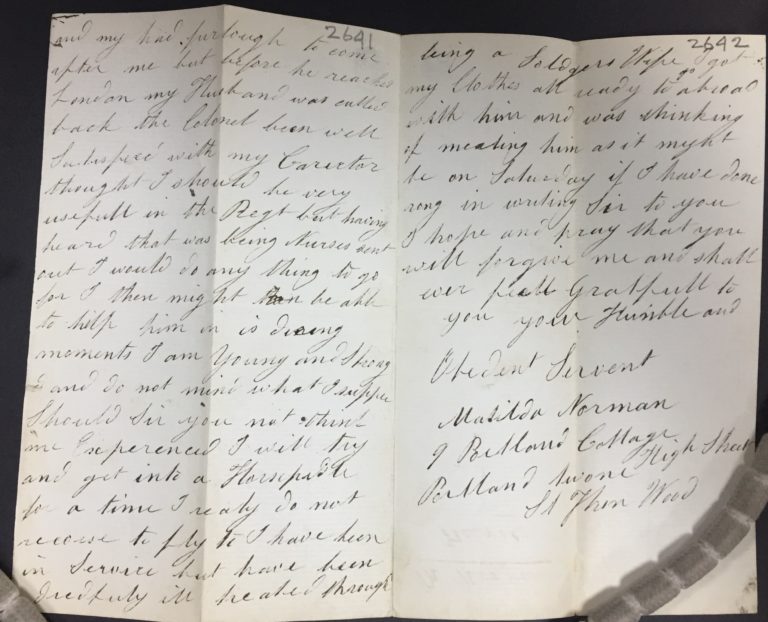

The collection also includes a number of emotive letters from the wives of soldiers. One woman, Matilda Norman, stated to the War Office:

‘I take the liberty of writing to beg a favour of you but hope and trust you will forgive the liberty but am almost breaking hearted I am soldgers [sic] wife and my husband is just gone out to the East.’

Imploring them that she ‘would do anything to go for I then might be able to help him'[ref]WO 25/264. Letter from Matilda Norman to the War Office, undated, no. 2640-2642.[/ref], Norman relays that her husband had recently enlisted in the 90th Light Infantry. With Nightingale’s insistence on experienced nurses only it is unlikely that Norman was ever selected. Sadly, her husband never returned; Campaign Medal records tell us that Septimus Norman of the 90th Light Infantry died on 9 February 1855 while serving in the conflict[ref]WO 100/32. Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 90th Foot. Available to download from Discovery. Name-searchable on Ancestry.co.uk in the ‘Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1949’ collection.[/ref].

Another soldier’s wife, writing in the third-person, stated that she had ‘heard by enquiry that none but positively trained nurses are appointed by government for such post in the East’ but ‘unable from her own resources to proceed to the Crimea yet deeply anxious to be at hand should any casualty, whether from climate or warfare, over take her husband she would most thankfully accept any occupation there…'[ref]WO 25/264. Letter from soldier’s wife to the War Office, 28 February 1855, no. 2651-2654.[/ref]. It is not known whether the enquirer was selected to go over to the Crimea.

After the Crimea War

Following her return to England, Nightingale endeavoured to reform military nursing and improve hospitals. In 1858 she compiled a meticulous report ‘presented by request to the Secretary of State for War’ entitled ‘Notes on matters affecting the health, efficiency, and hospital administration of the British Army: founded chiefly on the experience of the late war’. She noted the high sickness rates of the army even during peacetime, and observed that the mortality of army pensioners was even higher if figures included those who died within 12 months of being pensioned[ref]F Nightingale, ‘Notes on matters affecting the health, efficiency, and hospital administration of the British Army: founded chiefly on the experience of the late war’ (London, 1858), pp. 256-257.[/ref]. Her statistical analysis was well-respected and she became the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society in 1858.

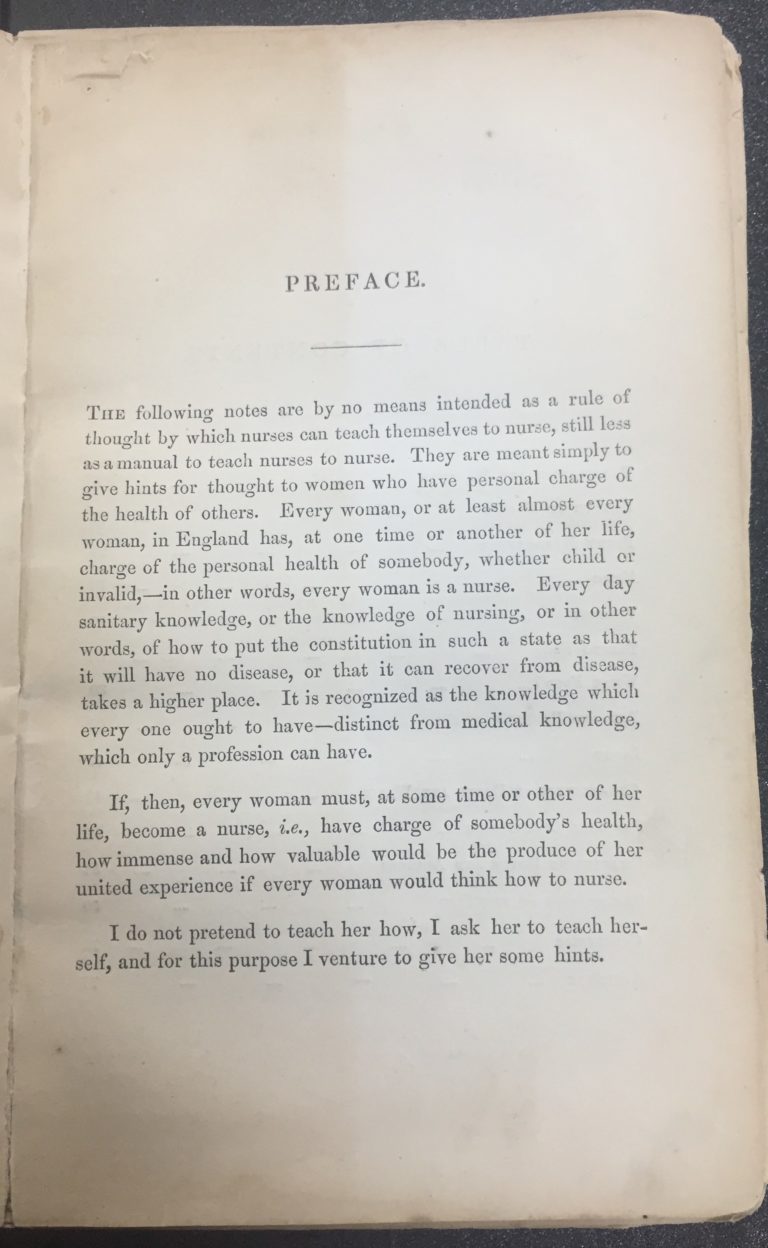

Nightingale’s interest in reforming nursing was not just focused on the military. In 1859 her book ‘Notes on Nursing’, a general advice book aimed at women from all walks of life, was published. Reprinted throughout her lifetime, the book noted that ‘every woman is a nurse’ as ‘every woman must, at some time or other of her life, become a nurse, i.e. have charge of somebody’s health.’

In 1860, Nightingale established the first secular nursing school at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, set up from public donations. She spent the rest of her life promoting nursing as a profession and undertaking work on hospital design.

Nightingale’s legacy

On St George’s Day 1883, Queen Victoria introduced the Royal Red Cross Medal to recognise exceptional service by military nurses; the registers of which are held at The National Archives[ref]WO 145/1. Registers of Recipients of the Royal Red Cross, 1883-1918.[/ref]. It was given ‘upon any ladies, whether subjects or foreign persons, who may be recommended by Our Secretary of State for War for special exertions in providing for the nursing of sick and wounded soldiers and sailors of Our Army and Navy'[ref]The London Gazette, 27 April 1883, p. 2239.[/ref]. The first recipient of the medal was Florence Nightingale.

Renowned for her pioneering work in her own time, Nightingale’s influence has continued to be recognised after her death in 1910. Nursing decorations have been named after her and International Nurses Day falls on her birthday. More recently, the temporary hospitals constructed across the country as a result of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic have been named after Nightingale, the woman widely acknowledged to be the founder of modern nursing.

Further reading

The National Archives ‘Military Nursing’ research guide.

F Nightingale, ‘Notes on Nursing’ (London, 1959) DT 15/1. Visit the Wellcome Library for free digital access.

F Nightingale, ‘Notes on matters affecting the health, efficiency, and hospital administration of the British Army: founded chiefly on the experience of the late war’ (London, 1858). Visit the Wellcome Library for free digital access.

F Nightingale, ‘Report upon the state of the hospitals of the British army in the Crimea and Scutari’ (London, 1855) in WO 33/1. Visit the Wellcome Library for free digital access.

Download a free ‘Florence Nightingale’ lesson pack for KS1 and KS2 from The National Archive’s Classroom Resources, created by our Education and Outreach team.

The Florence Nightingale Museum, Nightingale in 200 Objects, People & Places.

Thank you for allowing me the opportunity to read the fascinating history of the life of Florence Nightingale. I am sure that Florence would be very proud of the courageous and dedicated nurses that we have supporting the sick during these challenging moments in time, which of course will eventually become a part our own history.

Surprised to see no mention of the fact that the father of Florence adopted the surname Nightingale as a condition of inheritance

Thank you. Extremely well done – very interesting documents

I hope there will be a Part 3 which describes Nightingale’s contribution to the development of statistics.

Thank you nicely written details and enjoyed. I am interested in the names of the other nurses who worked with florence nightingale. Best Wishes onwards