On Friday, a new film version of the well-known First World War play ‘Journey’s End’ was released in cinemas. Depicting what life was like in a section of a trench leading up to the beginning of the Spring Offensive, one of the standout techniques is how the claustrophobia of the trenches is conveyed, and the tense sensation of waiting for something to happen. With the Spring Offensive not beginning until 21 March 1918, it seemed too early still to write a blog post about this; therefore the focus of this blog will be the effects that fighting could have on the mental health of the men at the Front – something that I think is clearly conveyed throughout both the original play and this new film.

We have many documents in our collections relating to neurasthenia, shell shock and mental health in both men and women from the period of the First World War. With the focus of this blog being to link to ‘Journey’s End’, the primary focus will rest with the men in the trenches. The constant shell fire, the ceaseless waiting, the unending monotony could all have an impact on the men stuck in this atmosphere.

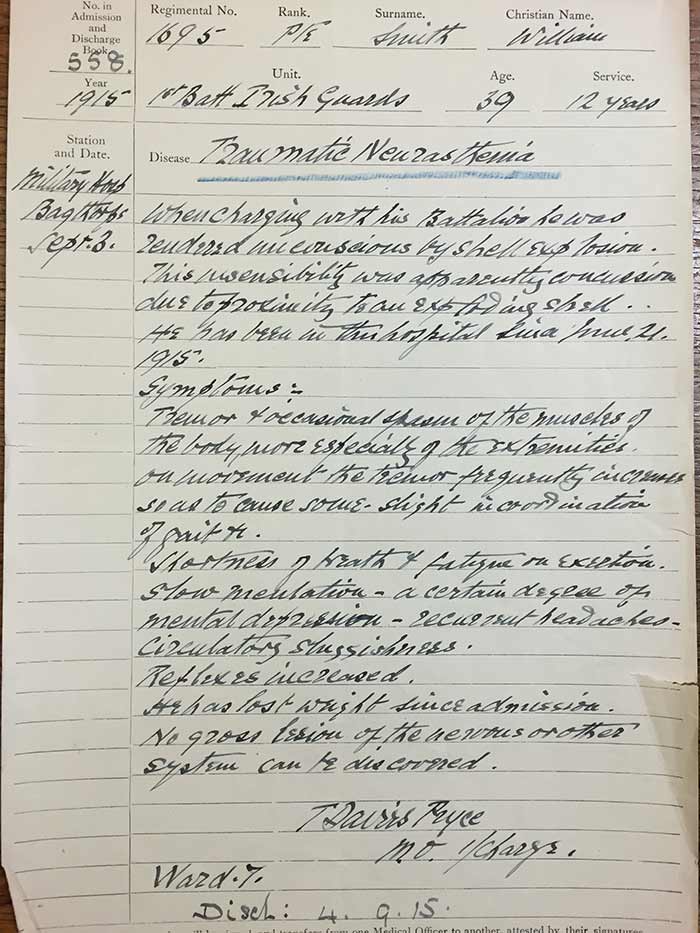

Records series PIN 26 and MH 106 are both excellent collections for researching this – in particular the medical side of things – showing how men could be affected long term. The causes of these conditions could range from something causing physical injury to trauma occurring inside the mind. The symptoms could also be wide-ranging. For example, one man was rendered unconscious by a shell explosion which happened in close proximity to him. He then spent months in hospital, due to the symptoms that he showed after this incident. These included: tremor and occasional spasm of the muscles of the body, which were more noticeable in the extremities; a certain degree of mental depression; and recurrent headaches. The diagnosis on his medical case sheet reads ‘traumatic neurasthenia’.

Medical case sheet; catalogue reference: MH 106/2101

Another man was sent to hospital suffering from ‘neurasthenia’ with his case sheet stating that his father had drowned on the Lusitania and his brother had been killed in France. Since then he had been depressed and sleepless. I have added this example to show that troublesome symptoms weren’t always just due to something that had physically happened to the person in question.

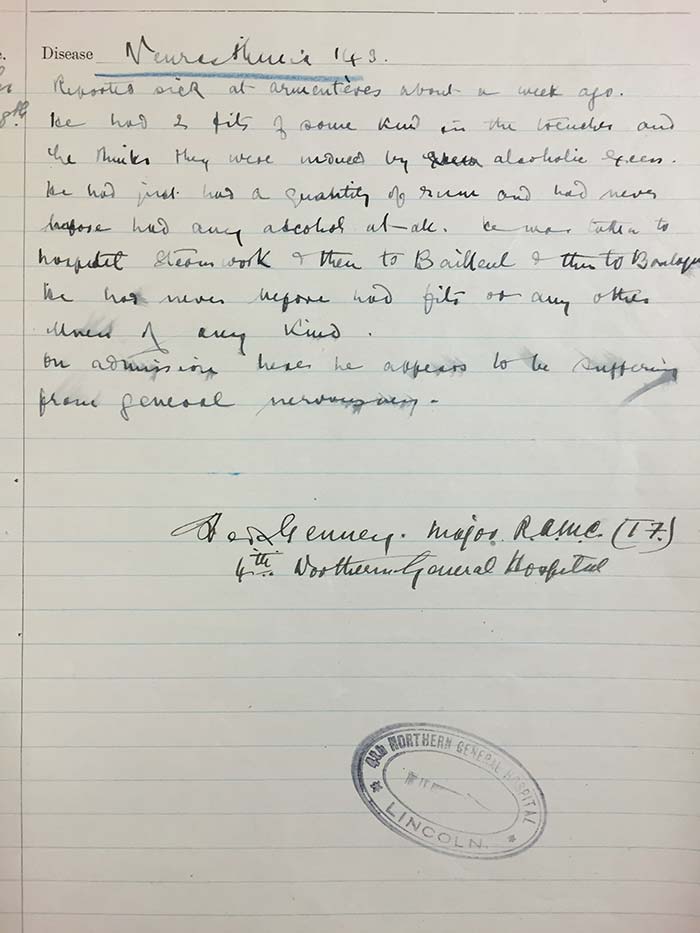

‘Neurasthenia’ was apparently a catch-all diagnosis, or at least that is what the case sheets seem to show. The causes and symptoms are wide-ranging , sometimes including things that nowadays might seem unrelated. For example, there was one man who reported sick after he had a fit of some sort in the trenches. He believed that this had been induced by the consumption of alcohol, or ‘alcoholic excess’ as he refers to it. Not long before the fit occurred, he had just had a quantity of rum: the first time that he had ever consmed alcohol in his life. Before this, he had never had any sort of fit or serious illness. Again, his case sheet reads ‘neurasthenia’. The mention of alcohol also links back to ‘Journey’s End’ – one of the things we learn early on is that Stanhope is reliant on whisky to help him cope with being at the Western Front.

Medical case sheet; catalogue reference: MH 106/2101

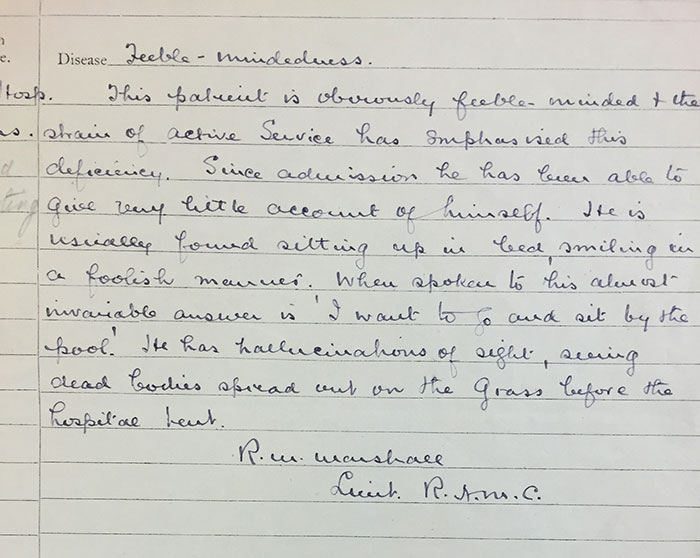

One case sheet reads ‘feeble-mindedness’ at the top: it makes a direct correlation between the strain of active service and this becoming more obviously an issue. This case is particularly severe as the man in question suffers from hallucinations, in particular seeing dead bodies spread out on the grass in front of the hospital tent. These hallucinations occur for around a fortnight; thereafter he cannot sleep well and his knees jerk a lot, as well as his memory apparently declining since being in France. This perfectly highlights the much longer-term effects that trauma at the Front could have on a man.

Medical case sheet; catalogue reference: MH 106/2102

For the majority of men, they had to live with these conditions – mostly after a hospital stay they ended up back at the front lines. A good example of this is the famous war poet Siegfried Sassoon. Some men unfortunately took their own lives. And for some, like 2nd Lieutenant Eric Poole, had their lives taken from them.

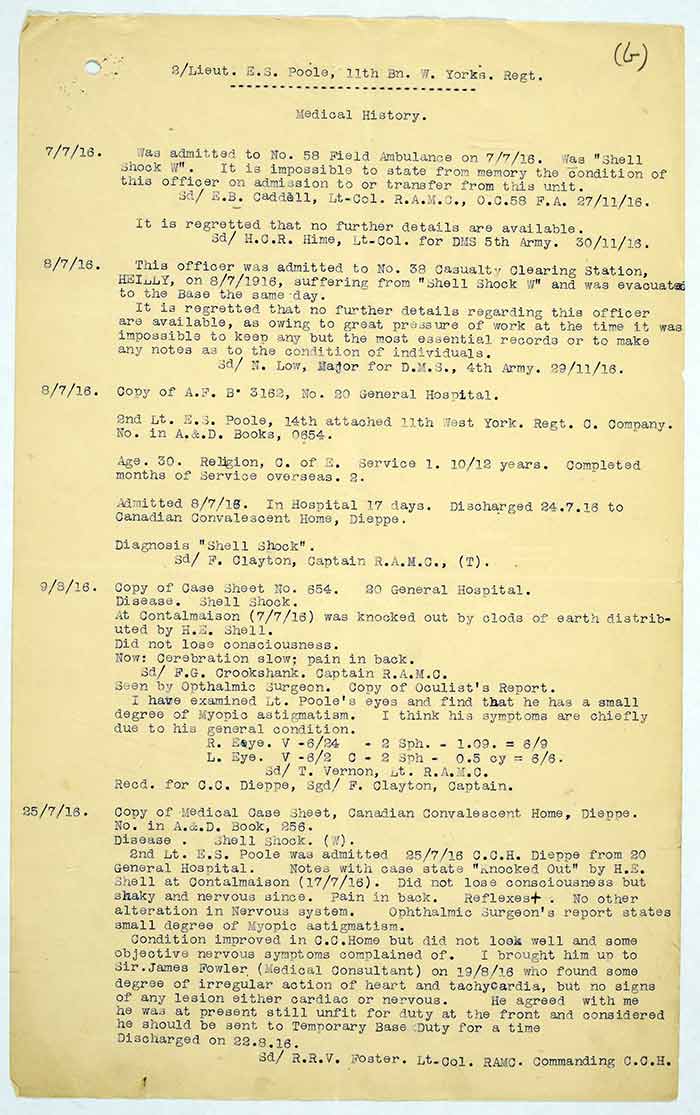

According to the medical history sheet compiled for Poole’s court martial in November 1916, he suffered from shell shock after being hit by clods of earth thrown up from enemy shell fire during fighting on the Somme on 7 July 1916. After a period of recuperation, Poole was returned to duty with his battalion at the end of August. In his testimony at his trial, Poole said that the shell shock injury caused him to ‘at times get confused and… have great difficulty in making up [his] mind’. It was in this condition that he wandered away from his platoon on 5 October 1916.

A few days later Poole was apprehended by the military police. In late November 1916, he was tried by court martial for desertion when on active duty. He was found guilty and sentenced to death by the firing squad. He was executed in Poperinge on 10 December 1916.

Medical history of Eric Poole; catalogue reference: WO 71/1027

Shell shock and mental health in the First World War is a huge topic: I could not cover it in much depth in this blog. However, I hope it gives some insight into one of the major themes of ‘Journey’s End’ – and something that affected so many men who were in the trenches, like Stanhope et al.

JUST USED THIS INFO FOR A LESSON ON 1ww INJURIES AT GCSE. MOST USEFUL

thanks

My grandfather suffered PTSD until his death in 1928. Grandmother did not qualify for war widow’s pension. Was told to put her 2 youngest children into a children’s home, and get a job. Brutal!

My Grandfather re-enlisted in 1914 and survived until September 1918 when he suffered a major facial injury. He was unable to work again and died in Bristol Mental Hospital in 1938. As you say, Brutal!!

This was an incredibly insightful source for my history essay on the mental effects of trench warfare! Your writing is very empathetic, and I appreciate how you don’t try to sugarcoat any of the hallucinations or outcomes of PTSD. Love your work, and thank you so much!