The copyright records held at The National Archives are a fantastic source for the study of early photography. These records include photographs submitted from copyright between 1862 and 1912, along with entry forms detailing the names and addresses of the copyright owners and authors. These records can provide information about the lives of early photographers, about whom often little is known.

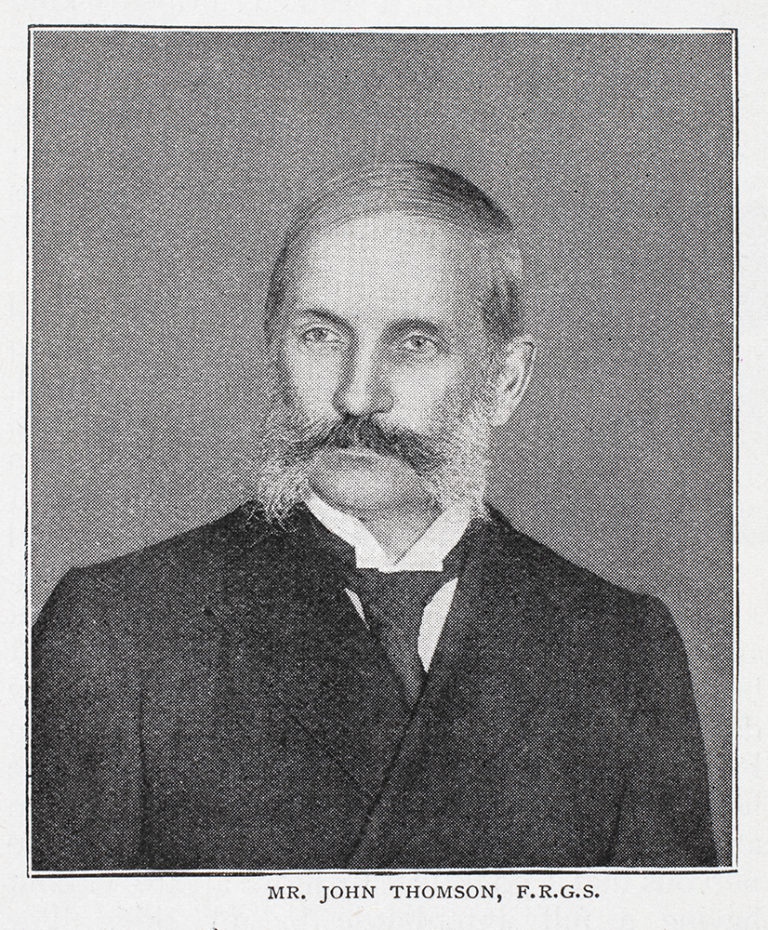

One photographer of note appearing in the copyright records is John Thomson. He was perhaps the first photojournalist in the modern sense, as he used photography to document places and people he encountered in his travels at home and abroad. He travelled around East Asia photographing a broad cross-section of society from ordinary people to the aristocracy. He later returned to Britain and continued in this vein, documenting the experiences of the poor, while at the same time taking commissions from high society.

Improvements in photographic processes enabled Thomson to reproduce his photographs for public consumption in a way that had been impossible before, earning him fame in photographic circles[ref]Elliott S Parker, ‘John Thomson, 1837-1921 RGS Instructor in Photography’, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 144, No. 3 (Nov. 1978), https://www.jstor.org/stable/634822 Accessed: 2nd April 2020, p. 463.[/ref].

John Thomson was born in Edinburgh in 1837 and began to learn the scientific principles of photography in the early 1850s as an apprentice to a maker of optical and scientific instruments. He also spent this time attending classes at the Watt Institution and School of Arts[ref]’The Photographs of John Thomson’, Digital Library, National Library of Scotland. https://digital.nls.uk/thomson/ Accessed 3rd April 2020.[/ref].

Travels in East Asia

In the early 1860s he decided to travel to Singapore to join his brother, who had set up a business as a watch-maker and photographer in the city[ref]Richard Ovenden, John Thomson (1837-1921) Photographer, Stationery Office (1997), p.6.[/ref]. This began a ten-year period where Thomson travelled around East Asia documenting his experiences.

He set up a photographic studio in Singapore and Penang, establishing himself as a portrait photographer for high-status individuals. This business enabled him to earn a good living and save funds to finance future expeditions. At the same time he developed a keen interest in the lives of ordinary people and spent time exploring towns and villages photographing and documenting the people he met[ref]James R Ryan, Photography, Geography and Empire, 1840-1914, Thesis submitted for PhD Royal Holloway, University of London (1994), p. 194.[/ref].

In 1866, he went on a gruelling expedition to Cambodia via Siam (Thailand) to photograph the Angkor Wat ruins. On the journey he suffered an attack of malaria, which left him unable to walk for some time. Mongkut, King of Siam (Thailand), whom Thomson had met in Bangkok, reportedly considered him insane for wanting to travel such a long way just to photograph some ruins[ref]Parker (1978), p. 465.[/ref].

Thomson returned to Britain for a year, where he lectured, published some of his photographs and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society[ref]Ibid., pp. 465-6.[/ref]. It is in this period where we see the first evidence of John Thomson’s career in The National Archives’ copyright records. Our earliest record of the photographer is an entry form dated 1866 where he gives his address as ‘Edinburgh, Scotland’ and registers nine photographs of Angkor Wat. While, unfortunately, copies of the photographs are not attached to the form, it is likely that these were registered in advance of the publication of his first book, Antiquities of Cambodia, in 1867.

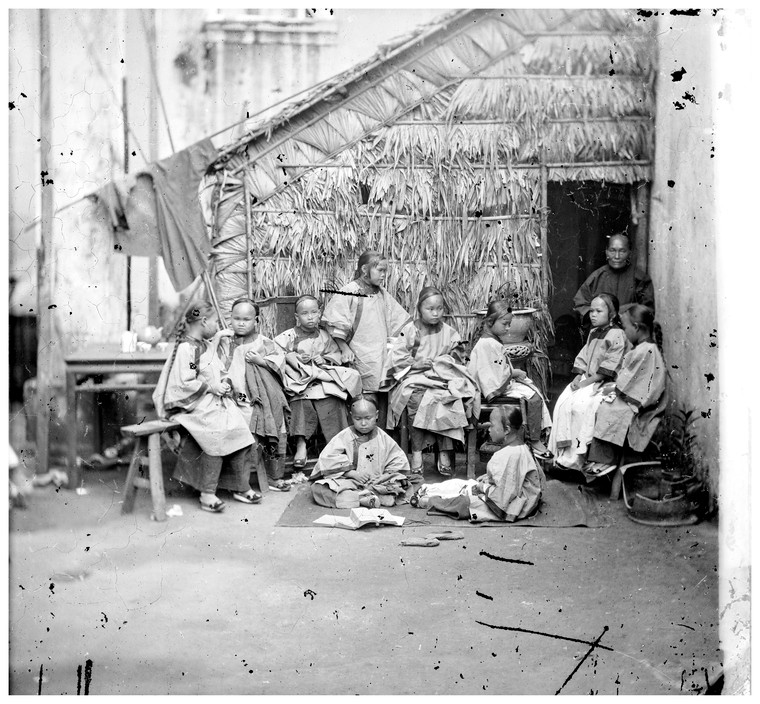

Returning to the East, he established a photographic studio in Hong Kong and from there took many more expeditions across China between 1868 and 1872[ref]Ryan (1994), p. 194.[/ref]. He visited areas which had been relatively unexplored by westerners due to travel restrictions. His photographs are broad-ranging in subject and so provide a fascinating record of buildings, landscapes, lifestyles, costume and rituals of 19th-century China.

However, his photographs also recorded a China which was beginning a period of decline. Huge population growth put pressure on food and resources, and government administration did not expand to cope, leading to terrible poverty, particularly in rural areas. Thomson’s work gives an insight into this poverty, particularly through his photographs of foundling hospitals and discussions of the experience of families resorting to female infanticide[ref]John Thomson, Through China with a Camera (Read Books Ltd, 2016).[/ref].

Photographic processes

Thomson showed a keen interest in how the art of photography was advancing during his career, and wrote about his own role in championing the use of photography in exploration.

Lack of time and opportunity constrains the gifted traveller, too often to trust to memory for detail in his sketches, and by the free play of fancy he fills in and embellishes his handiwork until it becomes a picture of his own creation. An instantaneous photograph would certainly rob his effort of romance, but the merit would remain of his carrying away a perfect mimicry of the scene presented, and an enduring evidence of work faithfully performed.

John Thomson, ‘Photography and Exploration’, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, Vol. 13, No. 11 (Nov., 1891), pp. 669-675

Thomson used the wet collodion process of photography, which was invented by F Scott Archer in 1848. It produced a high-resolution image, however it required the glass plate to be coated, sensitized, exposed and developed within the span of about 15 minutes. In the case of travel photography, this meant that Thomson had to erect a temporary darkroom in a tent wherever he stopped to take photographs[ref]John Thomson Geographical photography, Scottish Geographical Magazine, 23:1 (1907), DOI: 10.1080/00369220708733708, p. 16; Parker (1978), p. 465.[/ref].

Thomson wrote about his experiences in China, accompanied by his photographs, in his 1874 four-volume book titled Illustrations of China and its people. He wrote about how advances in photography not only rendered it effective for travellers to use to record their observations, but also meant that photographs could be reproduced accurately on a mass scale, allowing the general public to relive the experiences of the traveller[ref]John Thomson, Illustrations of China and its people. A series of two hundred photographs, with letterpress descriptive of the places and people represented, Volume I, (London, 1874).[/ref].

It is a novel experiment to attempt to illustrate a book of travels with photographs, a few years back so perishable, and so difficult to reproduce. But the art is now so far advanced, that we can multiply the copies with the same facility, and print them with the same materials as in the case of woodcuts or engravings. I feel somewhat sanguine about the success of the undertaking, and I hope to see the process which I have thus applied adopted by other travellers; for the faithfulness of such pictures affords the nearest approach that can be made towards placing the reader actually before the scene which is represented.

John Thomson, Illustrations of China and its people. A series of two hundred photographs, with letterpress descriptive of the places and people represented, Volume I, London, 1874.

Thomson’s photographs were reproduced in these four volumes using the new Woodburytype process, invented in 1864, which was praised by Thomson and reviewers as providing unparalleled fidelity[ref]Parker (1978), p. 468.[/ref].

Thomson also wrote about the attitudes of the Chinese people to photography. He wrote that for many people, his camera was a ‘dark mysterious instrument’ which was considered ‘the forerunner of death'[ref]Thomson (1874).[/ref]. However he also praised the skill and expertise of Chinese photographers, writing that, near his studio, there was a ‘score of Chinese photographers who do better work than is produced by the herd of obscure dabblers’ in England'[ref]John Thomson, ‘Hong Kong photographers’. British Journal of Photography (1872).[/ref].

Street life in London

On this return to England, John Thomson turned his attention to the people of London and collaborated with socialist journalist Adolphe Smith. Together they photographed and interviewed people they met on the streets of London – including locksmiths, flower sellers, shoeblacks, labourers, cabmen, dustmen and musicians – building up a detailed picture of the London poor at the time.

The photographs and accompanying detailed descriptions were published in monthly instalments as Street Life in London in 1876 and 1877. The photographs record in sharp relief the plight of the poor in Victorian London, and the engaging descriptions give an insight into the life stories of those depicted. The volume is considered an early pioneering example of documentary photojournalism[ref]’Street Life in London’, LSE Digital Library, https://digital.library.lse.ac.uk/collections/streetlifeinlondon, accessed 6th April 2020.[/ref].

Thomson and Smith wrote about their objectives in the preface to the published work, explaining that their aim was to present both the familiar and the unknown aspects of London street life[ref]John Thomson and Adolphe Smith, ‘Preface’, Street Life in London (Dodo Press, 2009).[/ref].

We have selected our material in the highways and the byways, deeming that the familiar aspects of street life would be as welcome as those glimpses caught here and there, at the angle of some dark alley, or in some squalid corner beyond the beat of the ordinary wayfarer. It also often happens that little is known concerning the street characters who are the most frequently seen in our crowded thoroughfares. At the same time, we have visited, armed with notebook and camera, those back streets and courts where the struggle for life is none the less bitter and intense, because less observed. Here what may be termed more original studies have presented themselves, and will help to complete what we trust will prove a vivid account of the various means by which our unfortunate fellow-creatures endeavour to earn, beg, or steal their daily bread.

John Thomson and Adolphe Smith, ‘Preface’, Street Life in London, 1877

London high society

Apart from an expedition to Cyprus in 1878 when Thomson became the first photographer to survey the island, he remained in Britain for the rest of his life. While Street Life in London was no doubt Thomson’s most successful and well-known work, he made his living in London by photographing members of British high society. He set up a portrait studio first in Buckingham Palace Road and then at 70a Grosvenor Street.

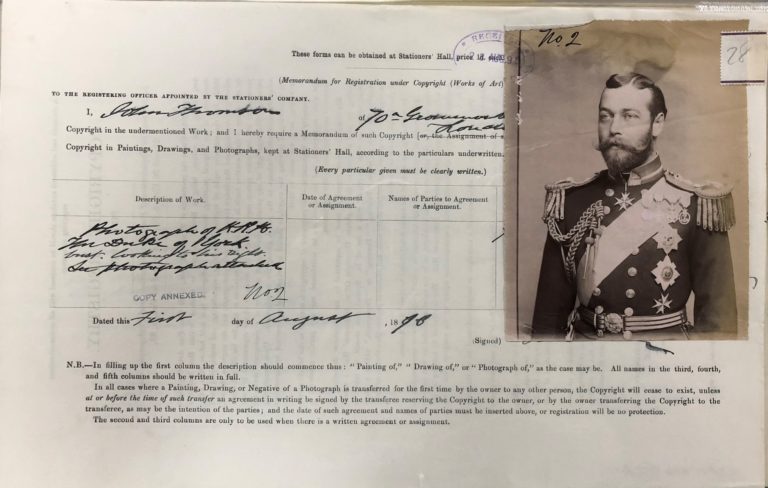

In 1881, Thomson was appointed photographer to the British royal family by Queen Victoria. He took many photographs of the Royal Family and other members of the aristocracy in the 1880s. At least one photograph of Queen Victoria attributed to John Thomson can be found in the Royal Collection[ref]See Royal Collection Trust, Queen Victoria (1819-1901), 1887, RCIN 2002098, https://www.rct.uk/collection/2002098/queen-victoria-1819-1901?language=es, Accessed: 6th April 2020.[/ref].

It appears that John Thomson registered many photographs for copyright in the 1880s and 1890s. In The National Archives’ copyright records, photographs of Queen Victoria taken by a John Thomson giving the address ‘Lilly Bank, Hillside Road, Tulse Hill Park, London’ can be found. In other records, his address is given as ‘The Grange, Leigham Court Road, Streatham, London’. It is presumed that this is the same John Thomson and he simply had multiple studio addresses at the time, although further detail about this is currently unknown.

We also hold 79 copyright records for John Thomson at his Grosvenor Street address registered between 1888 and 1899. Famous subjects include banker Leopold de Rothschild, sugar merchant and philanthropist Sir Henry Tate and the Duke of York (the future King George V).

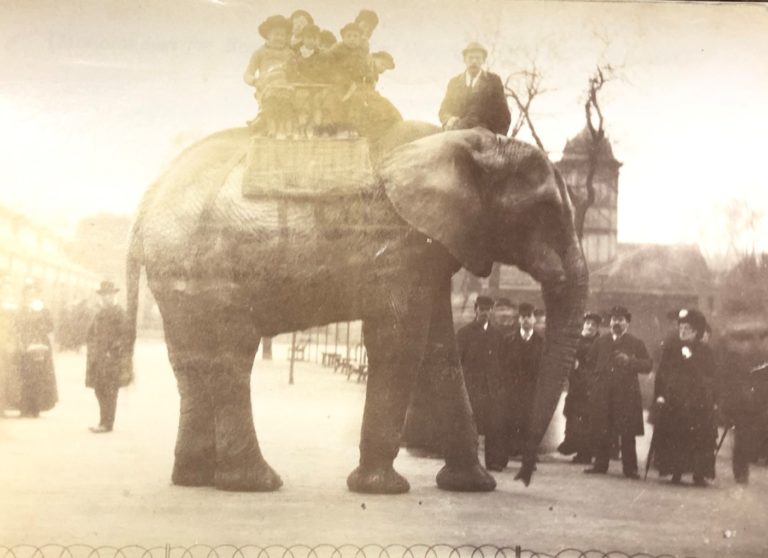

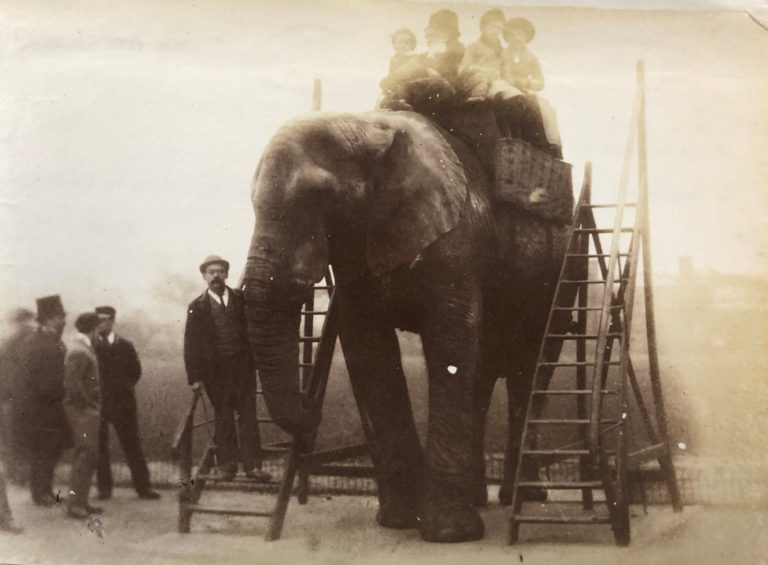

Jumbo the elephant

One set of photographs stands out among John Thomson’s copyright records. These are seven photographs taken of Jumbo, a famous African elephant who lived at London Zoo, all registered in March 1882. Jumbo was famous for his size (the term ‘jumbo’, used to describe something large in size, derives from his name) and he was popular for carrying children and adults on his back.

On the copyright entry forms, John Thomson’s address is listed as ’60 Acre Lane, Brixton, London’ and the copyright owner is William Luks, a publisher and dealer in photographic and fine art. This suggests that Thomson was commissioned by Luks to take these photographs of Jumbo.

Among the entry forms for March 1882 are several other images of Jumbo, produced by other creators. The reason for the particular interest in Jumbo at this time was that in that year, Jumbo was sold by the London Zoological Society (LZS) director Abraham Bartlett to Barnum, Bailey and Hutchinson circus in the USA. The press presented the sale as a national insult and a public outcry ensued, as people begged LZS to reconsider sending Jumbo to America[ref]Susan Nance, Animal Modernity: Jumbo the Elephant and the Human Dilemma (Springer, 2015), p. 10[/ref].

Ultimately, their efforts failed and Jumbo was transported by ship to New York in April 1882. These photographs are evidence of the press and public interest in Jumbo during his last few months in London. Jumbo’s story ended sadly, as, three years after the sale, he was hit by a train in St Thomas Ontario and died soon after[ref]Ibid.[/ref].

John Thomson and the archive

John Thomson continued writing about photography and in particular its usefulness as a tool for exploration. He became an Instructor in Photography for the Royal Geographical Society in 1886 and was elected a Life Fellow in 1917. He kept up with advances in photographic processes and continued to publish in various journals including the British Journal of Photography. He was also an early experimenter in colour photography in his later years[ref]Parker (1978), pp. 469-70.[/ref].

Only part of John Thomson’s career is identifiable in the copyright records held at The National Archives. This tells us something about the nature of the records themselves. Photographers tended to register those images that they intended to publish commercially and that they considered to be in danger of being copied. This may be why Thomson’s portraits of notable individuals are highly represented among the records, as well as more traditional journalistic photographs such as those of Jumbo the elephant. The additional information entered into copyright entry forms also gives us evidence for the addresses individuals were using at the time and the dates they were working on particular projects.

John Thomson was a pioneer in travel photography and documentary photojournalism. His full and varied career has left us with a series of remarkable images which allow us an unparalleled insight into the experiences of people in the 19th century, both in London and East Asia.

Further reading

John Thomson, Illustrations of China and its people (1874): https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Illustrations_of_China_and_Its_People

Through the Lens of John Thomson – Worldwide Photography Exhibition Tour: http://www.johnthomsonexhibition.org/

Michael Wood, The Chinese photographs of John Thomson (1837-1921), seminar held at SOAS University of London in 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R8swqEugzpw

John Thomson, Street Life in London (1876-7), LSE Digital Library: https://digital.library.lse.ac.uk/collections/streetlifeinlondon

I think the correct name for London Zoo is the Zoological Society of London (ZSL).

What a fascinating blog and so thoroughly researched. Thank you!

Fascinating story, grazie.

I have some photos of my Grandmother that was born in Hong Kong in 1903.

I always wonder who the Photographer was. They are beautiful. I would be happy to send a copy to the National Archives.

Most of John Thomson images were printed in different graphic media. He seems to have avoided when ever possible using the albumen process because of its tendency to fade quite quickly even when gold toned. As gold toning was essential to ensure a degree of longevity many photographer tried to make their toning baths last beyond the point of exhaustion which resulted in the print appearing to be fine when in fact the were ‘sulphur toned’, most of which would have discoloured and faded quite quickly. For this reason Thomson first of all used the carbon transfer process and then the collotype process. So the best surviving examples of his work survive as the images he used to accompany his texts in ‘Illustrations of China and its People’; ‘Foo Chow and the River Min’ (collotype and carbon processes respectively). Wider distribution of his images and accompanying texts in several languages was achieved with the letterpress half-tone, wood cut, and lithographic print process. Although through these media he achieved a much wider distribution, the quality of the reproduction could not match that of the carbon and collotype processes, especially the latter. So it is, I believe, that he favoured the remediation of his work. He did use the woodburytype for Street Life in London but both the carbon and woodburytype process were limited in terms of the quantities that could be printed from a single matrix but the results were outstanding, unequalled virtually until the late 1970s.

I have two books written by Henry Mayhew, he wrote about Victorian England and interview street people, scribes and costermongers among many others.

Vert little about young Thomson’s work in Singapour & Penang…Already interested in social classes, native workers to which he will return in later tests in London.