The social order of late 18th and early 19th century Britain ordained that there was a strict distinction between the Officer class of the British Army and the rank and file, who Wellington famously described as ‘the scum of the earth’. In order to be an officer one was expected to be a gentleman born and bred. To some extent this changed during the Peninsular War when five to six per cent of the officers serving in the Army were promoted from the ranks. One such man was Isaac Chetham.

Isaac Chetham was born in Nottingham during the first half of 1781, the son of Edward and Mary Chetham (baptismal certificate in WO 42/8/C306). I have been unable to discover Edward Chetham’s occupation, but as his son could read and write, and had obviously had at least a basic education, I feel that he is more likely to have been a tradesman, or skilled craftsman, than a labourer. Whatever his occupation it would appear that Edward Chetham was not in a position to purchase a commission for his son when he joined the Army in 1797, at the age of 16. None the less Isaac rose steadily through the ranks and was commissioned as an Ensign in 1811.

Isaac was one of those who responded to a circular return sent out by the War Office in October 1828 to retired officers on full, or half, pay. This return is held at The National Archives (WO 25/753/49) and it gives considerable insight into the Army career of a man who fought in many of the major battles of the Peninsular War.

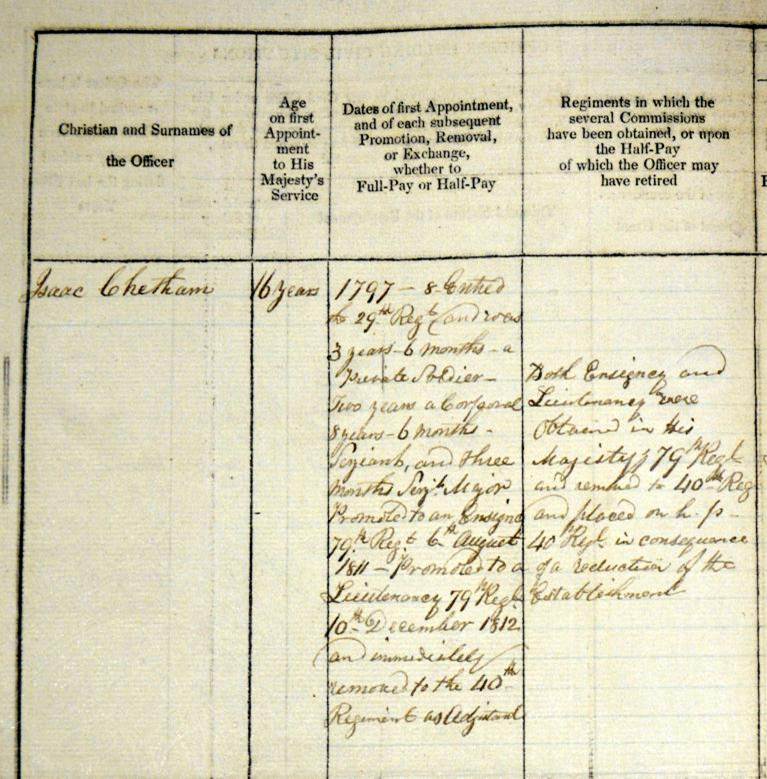

WO 25/753/49: Record of service: Extract from Isaac Chetham’s return recording his service in the ranks and as an Officer.

Isaac first enlisted in the 29th Foot and rose steadily through the ranks serving for three and a half years as a Private, two years as a Corporal, eight and a half years as a Sergeant, and three months as a Sergeant Major. His first taste of action came in 1799 when he was part of the Duke of York’s expedition to the Netherlands. He fought in the initial engagement at Callantsoog on 27 August and in the battles of 19 September, and 2 and 6 October. By 1802 Isaac was a Sergeant, still with the 29th Foot, and was stationed in Halifax Nova Scotia where on 7 December 1802 he married Mary Morel (marriage certificate: WO 42/8/C306). As Isaac records on his service return (WO 25/753/49), he and Mary went on to have three children: Mary Ann born on 15 September 1803; Edward born on 27 May 1805; and Elizabeth born on 11 August 1816.

In September 1807 the 29th Foot returned to England and in December the same year the Regiment left for the Peninsular. With the 29th Foot Isaac fought in five major battles: Rolica (17 August 1808), Vimerio (21 August 1808), Talavera (27-28 July 1809), Busaco (27 September 1810) and Albuhera (16 May 1811). At Talavera on 27 July 1809 a composite battalion of the 29th and 48th Regiments of Foot attacked three French Regiments on a hill known as the Cerro de Medelin. The 29th Regiment drove the French from the hill with a single volley and bayonet charge. The following morning the hill was hit by massed artillery fire followed by an assault by six French battalions advancing in column. The British defended the hill in line formation, overwhelming the French attack. The 29th Regiment of Foot captured two French colours in the bayonet charge and then drove the French from the field. On 12 September 1809 Wellington wrote:

‘I wish very much that some measures could be adopted to get recruits for the 29th Regiment, it is the best Regiment in this Army, has an admirable internal system and excellent Non-Commissioned Officers’

As a Sergeant of over six years standing Isaac Chetham was one of those ‘excellent Non-Commissioned Officers’. (1)

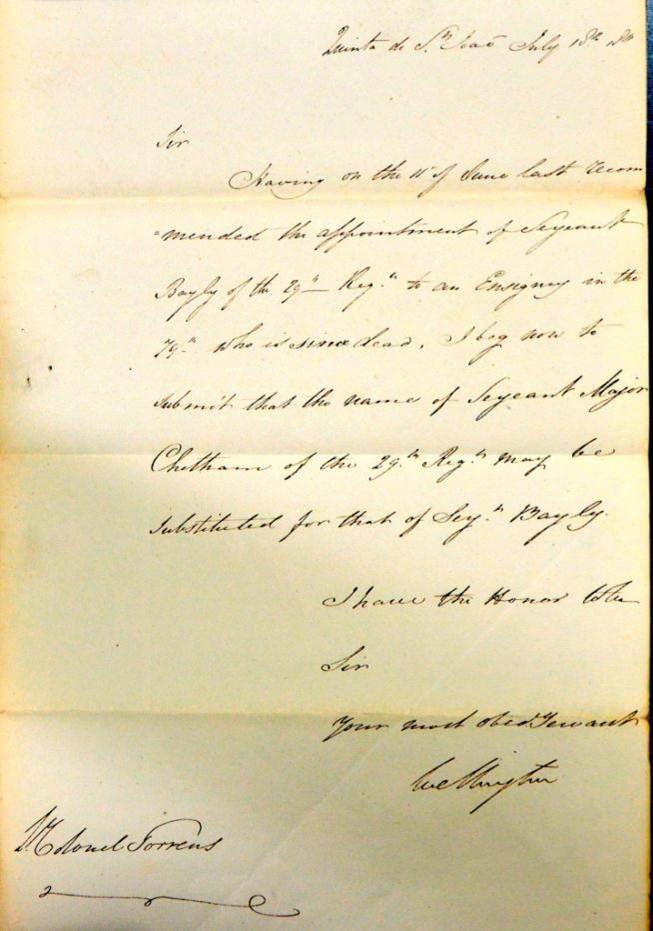

WO 31/328: Letter from Wellington granting the 1st commission to Isaac Chetham as Ensign in 79th Foot.

On 6 August 1811 Isaac, on Wellington’s personal recommendation, was commissioned as an Ensign in the 79th Foot (letter from Wellington: WO 31/328). With the 79th Foot he was present at the battle of Salamanca on 22 July 1812. On 10 September 1812 Isaac received a Lieutenant’s commission and was immediately removed to the 40th regiment of Foot. He saw action at the battles of Vitoria (21 June 1813), Orthez (27 February 1814) and Toulouse (10 April 1814). Very much against his own wishes on 24 February 1817 Isaac was placed on half pay with the reduction of the number of additional Lieutenants in the 40th Foot. He points out that despite having been severely wounded three times he has no pension. At the time he completed his return of service Isaac was living in Nottingham on half pay and had no military or civil employment. He died aged 73, from natural causes at his home in Nottingham on 19th October 1854 (death certificate: WO 42/8/C306).

When I first found out about Isaac Chetham I was intrigued by the story of a man who like Bernard Cornwell’s fictional hero Richard Sharpe was one of the relatively few men who rose from the ranks of Wellington’s Army to become a commissioned officer. I wanted to find out more about his Army career, and if possible about the man himself. From his return of service I have managed to piece together details of his Army career, both in the ranks, and as a commissioned officer. I have also learned a little of his personal history, and his life once the fighting was over. Two hundred years after the war in which he fought came to an end, I am pleased to feel that by piecing together information from some of the collections held here at Kew the lives and service of men like Isaac Chetham can still be remembered.

(1) The details of the battle of Talavera and the quotation from Wellington are taken from (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/29th_(Worcestershire)_Regiment_of_Foot)

I think he also appears in the 1841 census, living on Charles Town No 1 Street, Northowram, Halifax. He’s listed as Army HP (presumably half pay), and seems to be in a household with

Samuel Howarth (25), Alice Howarth (55), Arpha Howarth (22, born Yorkshire, England), Sarah Howarth (25, born Yorkshire, England), Ely Wilson (55, born Yorkshire, England), James Wilson (55, born Scotland) see HO 107/1303 Book 2 Folio 14 Page 21.

And in 1851 at 151 Mansfield Road, St Mary’s, Nottingham listed as Isaac Cheetham, (70) “Lieutt H pay 40 Rgt” with his wife Mary (who is shown as 6 years older than him, and from Cornwall), and grand-daughter Fanny Green (10, born Nottingham) plus a servant, Harriott Taylor (18, born Gloucestershire) see HO 107/2131 Folio 132 Page 38.

Thank you for your comment.

I was aware of the entries for Isaac Chetham in the 1841 and 1851 Censuses.I have also found an entry for his wife Mary in the 1841 Census, although the surname has been mis-transcribed as Chatham. She is living at their address in Mansfield Road, Nottingham with Elizabth and John Flather,presumably her daughter and son in law, and their baby son named Isaac. There is also a female servant named Mary Brown.

Also using Parish Registers accessed through the London Family Search Desk here at Kew I found an entry in the Bishop’s transcripts of the baptismal registers for St. Mary’s Nottingham recording the exact date of Isaac Chetham’s baptism: 3rd June 1781. Searches produced other entries in the baptismal, marriage and death registers that might possibly relate to other members of Isaac Chetham’s family. However more research would be neccessary to take that further; ideally at the local county record office.

Hi Erica and David,

Isaac Cheetham is my 5th Great-Grandfather and Fanny Green my 3rd Great-Grandmother, so you can imagine my surprise when I saw this blog!

I was aware of his service in the Peninsular War from Lionel S. Challis’s ‘Peninsula Roll Call’ and have been trying to find out more information, since I thought he seemed an interesting case as you have subsequently proved.

I believe there are a few more mysteries to unravel about his life and I’m working on those now.

If you Google “Isaac Cheetham” you’ll find My Family Archive where I keep my notes which will now need updating!

A big thanks from me for the work you have done here!

Hi Erica,

I am one of the Heritage Walks officers for the Nottingham Civic Society and I do the guided walks around the Nottingham General Cemetery and also the Church (Rock) Cemetery in Nottingham.

Isaac Chetham is buried in the General Cemetery and is one of the people I talk about on the guided walk around the cemetery.

Isaac has a large tablet of slate for a headstone and the wording on his headstone is as follows:

Sacred

to the memory of

Isaac Chetham

Adjutant of HM 40th Foot

who fell asleep in Christ Oct 19th 1854

aged 73 years

He was actively engaged in nineteen general

battles and sieges during the expedition to

Holland and the Peninsular War; and was

three times dangerously wounded.

He lived and died in the faith of the Gospel.

Also

Mary Chetham…….

I hope this is of interest to you.

It’s Bernard Cornwell, rather than Cornwall.

Dear Jonathan. Many thanks for pointing that out – we’ve corrected it now.

Hi Kevin. Interesting to hear you do these walks and include this Isaac Cheetham. My wife’s 2x Great Grandfather is also an Isaac Cheetham buried at Nott’m General cemetery. he though was born 1812 and died with a big funeral procession in 1895. Our Isaac Cheetham was enlisted in the 30th Foot where this Isaac was the 40th. Our Isaac for nearly 30 years in his retirement ran the Robin Hood Rifles Store on Rutland Street. the Robin Hood Rifles band played at his funeral. For 40 years he was the Trumpeter for the High Sheriff. My thought is our Isaac may be the son of this Isaac, but I haven’t made the connection yet. Lots of coincidences and similarities, but maybe that’s all they are. Do you know the grave of our Isaac Cheetham? You could talk about both Isaac’s. darryl

Isaac Chatham is my 5 x great Grandfather, and Mary his wife is my 3 x great Grandmother, I have only just found out about this and will visit their grave site as soon as possible..

So fascinating, thank you very much for your work

Hi Raymond how can that possibly be? Is it a typo? If Isaac and Mary are married how can one be a 5x Great and the other a 3x Great to you?

Since leaving my comment on the 16th April, I have found the two Isaac’s are indeed related, the Isaac of this article is the Uncle of our Isaac. Our Isaac’s father, Edward is a brother of Isaac senior.

Hi Darryl, its a mistake on my part.

I hold a photo of Isaac Chetham and a list of battles he fought in, which has been passed down through my family. We seem to have had some connection with him and at one time we had a sash with, reportedly, Frenchmen’s blood on it. I believe my parents returned the sash to someone who was more directly related, about 60 years ago. Does anyone know about this?