This blog contains details that some readers may find distressing.

‘If abortion were necessarily fatal or injurious, I should not now be here before you.’

These are some of the opening words of Stella Browne, abortion law reform campaigner, in her evidence to the 1937 Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion. At a time when abortions were illegal, Stella boldly offered herself as evidence that these procedures were the lived experience of many women.

As criminal abortion cases show, restrictive abortion laws did little to deter many women who found themselves with unwanted pregnancies. Because it drove abortion underground, women’s lives were often endangered.

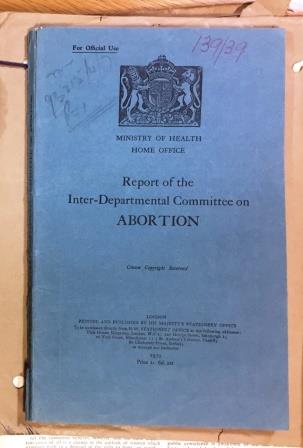

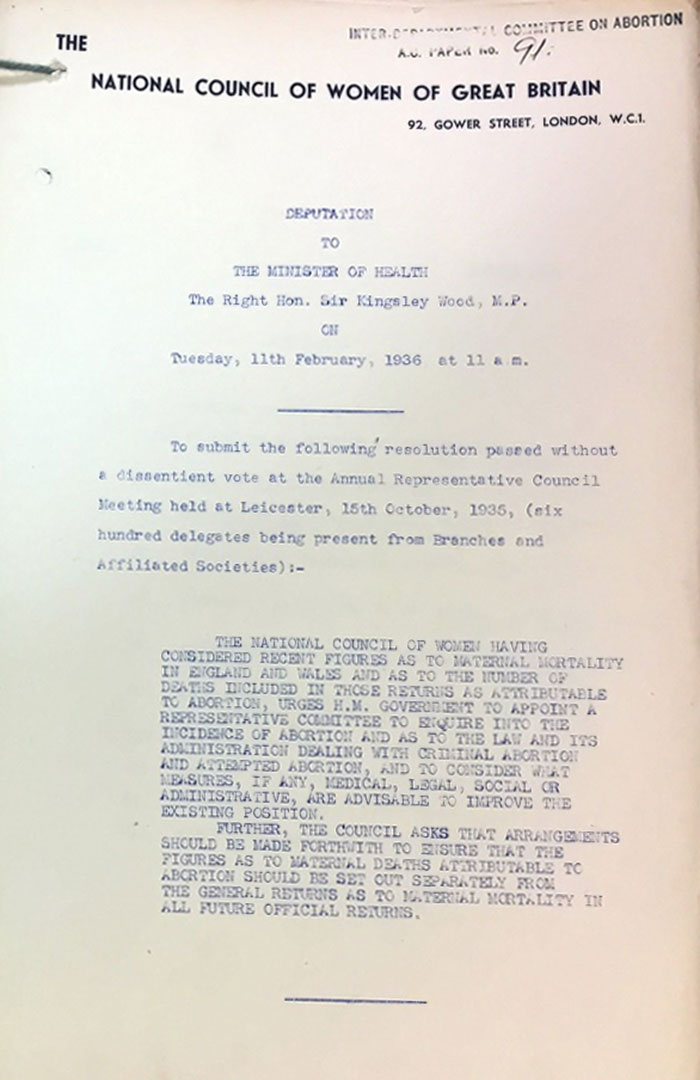

The crisis in maternal mortality rates in this era was a huge concern to the government. In 1936 a deputation from The National Council of Women of Great Britain added pressure to this existing concern, urging the government to appoint a representative committee to enquire into the incidence of abortion and to investigate the existing law. By 1937 these factors combined to trigger an Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion, also known as the Birkett Committee.

Deputation from The National Council of Women of Great Britain, Tuesday 11th February, 1936 at 11am. Reference: MH 71/18

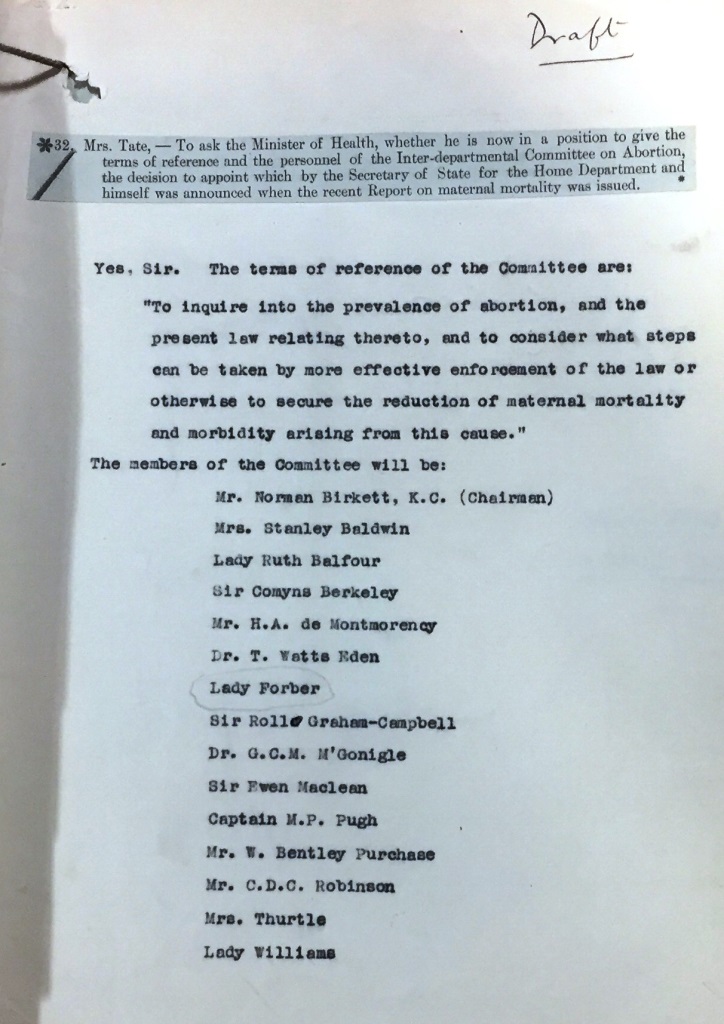

The terms of the committee were outlined as:

‘To inquire into the prevalence of abortion, and the present law relating thereto, and to consider what steps can be taken by more effective enforcement of the law or otherwise to secure the reduction of maternal mortality and morbidity arising from this cause.’

The committee was run between the Home Office and the Ministry of Health under the chairmanship of Mr Norman Birkett. The membership included a range of individuals, from medical professionals to women’s suffrage supporters.

Terms of reference and membership of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Abortion. Reference: MH 71/9

Evidence

Over the duration of the committee evidence was submitted by numerous groups, through countless memorandums and interviews. From the Union of Catholic Mothers of England – who had a membership of 20,000 – to the Eugenics Society and the National Birth Control Association, many voices were represented.

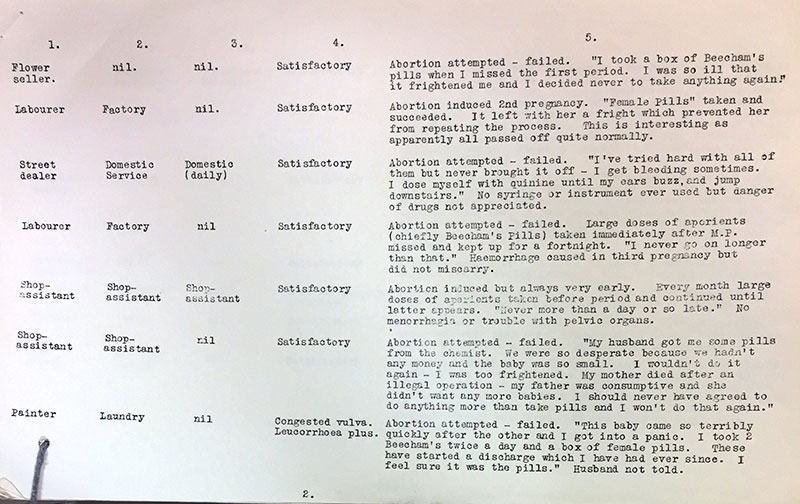

Government bodies were among those to submit reports, from the Director of Public Prosecutions, who saw the impact of criminal cases, to the Home Office and Metropolitan Police. One of the prominent submissions was from the Ministry of Health. This report identified three primary methods adopted by women to procure an abortion [MH 71/18].

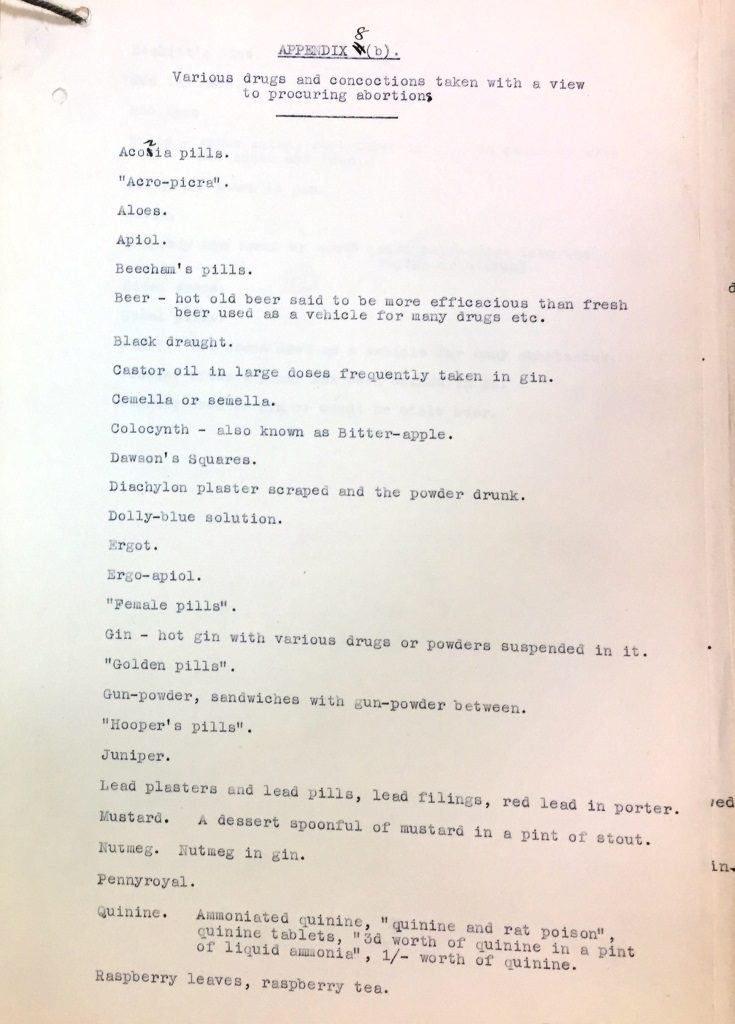

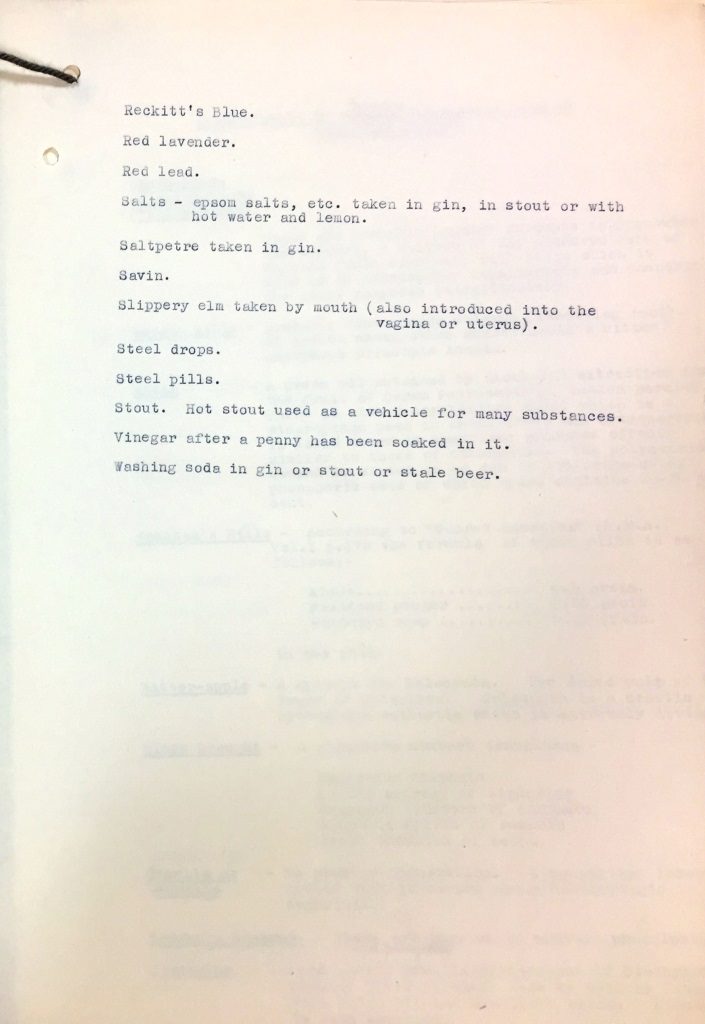

- Drug taking and drinking of various concoctions

- Indulgence in violent exercise

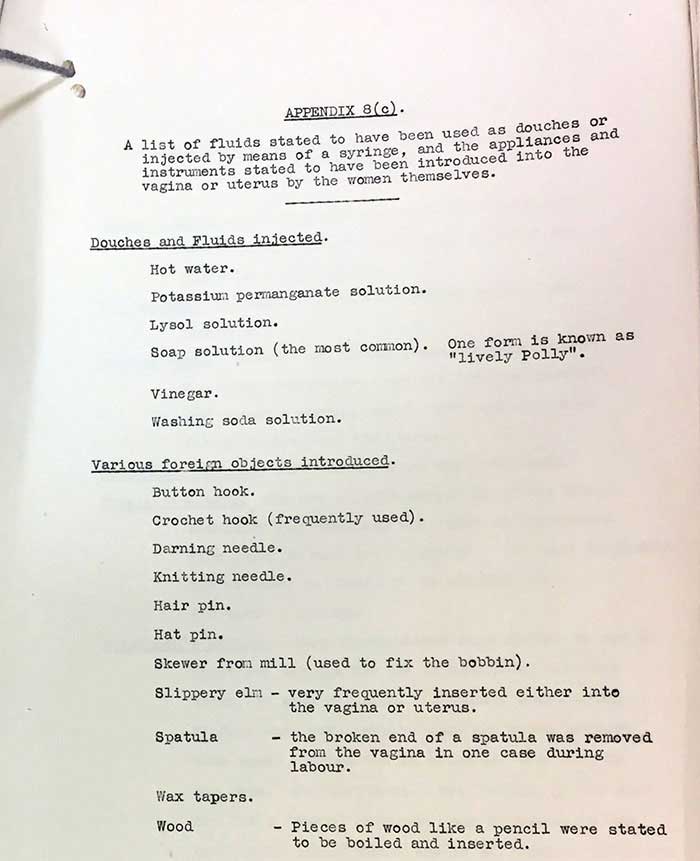

- The introduction of fluids, ‘slippery elm’ and various instruments into the vagina or uterus

Slippery elm bark was often used to self-abort: like many of the other unregulated methods, it was unhygienic and often caused haemorrhaging or sepsis. Part of the Ministry of Health’s evidence was a detail list of substances and items used by women to procure abortions.

- Ministry of Health evidence detailing various douches and objects used to procure abortions, Reference: MH 71/18

- Ministry of Health evidence detailing various drugs and concoctions taken with a view to procuring abortions, Reference: MH 71/18

- Ministry of Health evidence detailing various drugs and concoctions taken with a view to procuring abortions, Reference: MH 71/18

During the committee’s gathering of evidence in 1938, Alec Bourne was tried for performing an abortion on 14-year-old girl raped by soldiers. The case gathered substantial press attention. The eventual ruling established precedent for abortion on grounds of emotional and psychological trauma [MEPO 3/1008]. The inter-departmental committee seems to have given hope to campaigners in favour of reform.

Feminist perspectives: ‘mistress of her own body’

Among these submissions were a substantial number from feminist groups and practitioners working in gynecological and birth control facilities, recounting their first-hand experiences with affected women. Indeed, abortion law reform campaigns present a strong argument against the idea of waves of feminism, representing a continuity of campaigning from the 1930s to the 1960s, which is traditionally seen as more of a lull in feminist activism. While submissions of evidence reflect this era of prominent feminist campaigners, it was also a time of rising eugenicist views, many of which intertwined.

One of the key arguments for campaigners was the provision of better sex education and more accessible contraceptives. Representatives from the East Midlands Working Women’s Association Mrs Ivy Roche and Mrs Oakes (a midwife), argued for cheaper contraceptives and better advice at Municipal Clinics.

The evidence submitted by Dr Helena Wright, who proclaimed ten years’ experience at the progressive North Kensington Birth Control Clinic, argued that; ‘A very high percentage of abortions are preventable by removing the cause, i.e. an unwanted pregnancy.’ In her submission she explained the only way to do this was to provide an adequate national system of contraception. In this period, birth control provisions were sporadic, with the North Kensington clinic being one of the first specialised clinics in the country. [MH 71/25].

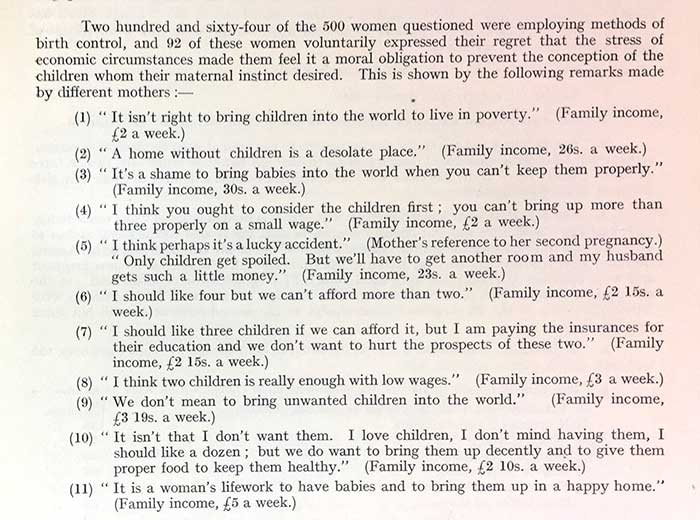

Furthermore, along with many other campaigners, she identified a class dynamic. Dr Wright believed, ‘The most frequent cause of abortions is an economic one’. This recurring theme shows women’s lack of options when faced with multiple mouths to feed. Evidence gathered by Dr Violet Russell showed similar concerns. Dr Russell gathered information from 500 predominantly working class, married women attending Kensington ante-natal clinics in the Spring and Summer of 1937: these women were, therefore, primarily ones who had previously had abortions or for whom abortions had failed. Once again the evidence strongly suggests that poverty and economic factors often pushed women into seeking abortions, even when they would have liked more children.

Section of report by Dr Violet Russell, based on 500 women surveyed. Reference: MH 71/21

Evidence from 500 women attending Kensington ante-natal clinics in the Spring and Summer of 1937. Reference: MH 71/23

Miss B A Henderson, student and tutor at the Friends Hall and Educational Settlement in Walthamstow, provided anonymised examples of various women’s experiences. This research identified an evident disparity between the treatment of married and unmarried women. It identified society as the problem: ‘those of unmarried women to whom there is no doubt a child would have been welcome – but society would not have welcomed it.’ Echoing the language of later pro-choice campaigners, Henderson argued that the people concerned should judge what was right for them, ultimately proclaiming ‘that it is elementary justice that a woman should be allowed to be the mistress of her own body.’ She advocated the legalisation of abortion. [MH 71/23]

The Abortion Law Reform Association was one of the most prominent campaigners for abortion reform in this era. Founded in 1936, it still continues to campaign under the name Abortion Rights. They strongly believed that reform was urgently needed. One of their key members was feminist, socialist and free love advocate Stella Browne, who in her own evidence spoke against the social pressures faced by men and women:

‘I do not think that to refrain from sexual intercourse out of fear, whether fear of the unknown, fear of venereal disease, fear of a baby, fear of ridicule, or fear of damages in the Divorce Court, or anything like that, is in any way a virtue. I think that sexual intercourse between those who love each other and understand each other is the most beautiful and valuable thing in life.’

The potential for reform

The final report was published in 1939 after the mass gathering of evidence and 47 committee meetings. Ultimately the report recommended therapeutic termination if pregnancy would endanger life and health. The committee’s conclusions did not present a radical revision of the law that many campaigners hoped for.

Indeed, by 1946 The National Council of Women of Great Britain issued a resolution to urge the government to introduce legislation in line with the recommendations. They were dismayed that the outbreak of war had prevented the report’s conclusions being more fully investigated. Nevertheless, the committee presented an important opportunity for activists and affected women to finally have their voices heard.