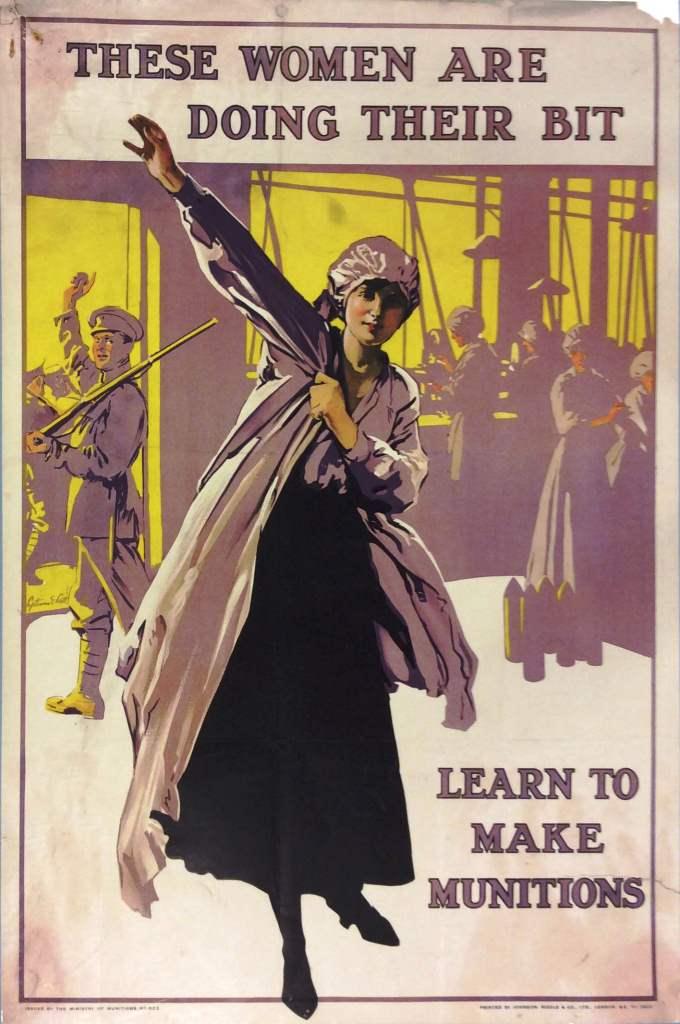

Poster showing female munitions workers: ‘These Women Are Doing Their Bit. Learn To Make Munitions’ (catalogue reference EXT 1/315/17)

There is a distinct image of female munitions workers during the First World War which occupies perhaps the most prominent place in Britain’s collective memory; the patriotic women who, though jaundiced and slowly poisoned, were proud to be doing ‘their bit’ and eager to take advantage of the new world of employment offered to them by the war.

But how accurate was this image? There was far more to the munitions workers on the world’s global homes fronts than this propaganda image suggests.

In this short blog series my colleague Chris and I will be looking at female munitions work during the First World War and address some misconceptions.

Labour shortage

In July 1916 it was estimated that 4,085,000 women were employed in Britain. This was an increase of 866,000, on the comparative figure for 1914, with a significant number of these new female workers directly filling men’s jobs. Conscription, as well as the 1915 ‘Treasury agreement’ with trade unions to allow ‘unskilled’ workers to be employed in previously protected trades, allowed these rapid increases of female employment.

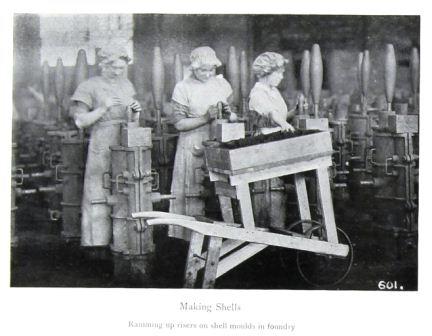

Image, captioned ‘Making shells’, from the government publication Women’s War Work (September 1916) (catalogue reference MH 47/142/1)

The war had not only increased the need for women to take up male roles, but also the country’s dependence on industrial productivity. As a result the Munitions of War Act was passed in 1916, bringing various industries under government regulation. [ref] 1. ‘Woman’s War Work in Great Britain’, Monthly Review of US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Vol 3, No 6, (Dec, 1916), pp788-789 [/ref]

As a result, female labour became not only more necessary, but better valued. A Ministry of Munitions labour report from September 1915 noted that:

‘The Labour Officer for London states that women are easier to train than unskilled men; they have a particular aptitude for various processes, such as viewing, and in repetition work are said to be less liable to tire. In intelligence, a girl of 18 is said to be equal to an unskilled man of 25.’ [ref] 2. TNA: MUN 2/27, report of 01/09/1915, p30 [/ref]

Indeed, so keen were the government to fill male places in industry that they even produced a photographic leaflet in February 1916 to demonstrate to sceptical employers women’s aptitude. This demonstrates their pride in women’s work in the factories.

Women themselves were also subjected to a propaganda effort. This poster describes working in munitions production as a way for women to ‘do their bit’; the smocked woman is compared to the soldier in the background, marching off to war, safe in the knowledge he’ll be kept in bullets by his industrious sisters. [ref] 3. TNA: EXT 1/315, part 21[/ref]

The motivation

Women were clearly needed in the labour force in many different roles – however despite this propaganda image perpetuated by the government was their motivation always patriotic?

In her book, Lloyd George’s Munition Girls, Monica Cosins vividly described the women on night shifts, getting the factory transport home, only to be back in time for preparing breakfast for their husbands and children. Munitions work was far from glamorous but it did offer a better wage than traditional roles such as domestic service and for some a freedom not to live with their employers.

Indeed many workers were moved away from their traditional family homes into hostels to be placed where the need was greatest. Stories of dozens of girls in segregated dormitories with only a cold water supply seem common.

The issue of strikes in munitions factories, to be addressed in a later blog, demonstrates munitionettes intentions were far from entirely patriotic, as many were willing to disrupt government services in a time of national crisis to gain a fair wage.

Greater value?

Industrial work of all kinds was far from new to a vast number of women, and rather than seize upon these new opportunities with unquestioning patriotic fervour, women’s organisations of the period instead called upon the female workforce to utilise their new leverage to secure decent conditions and wages.

One such organisation, the National Federation of Women Workers, a female only trade union, was particular vocal in its calls to as yet unorganised female workers. The January 1916 issue of the Federation’s magazine, the Woman Worker, plays with the language of the government’s propaganda: ‘Do your bit’ for the country’ female workers are encouraged, ‘do your bit for the women and children of Britain … If you do the man’s work, demand the man’s wage. Join the Union now.’

Women were greatly needed in the workforce – but was their work really valued? Our next post on equal pay will explore this question.

[…] Poster of female worker during WW1 […]

Was a medal ever issued to munitions workers? My mother worked on munitions as she always wondered

How were the women actually trained to do this work, who carried out this training and supervised them to ensure their work was suitable?

As an ex-training manager who was responsible for teaching people from very diverse backgrounds quite technical subjects up a professional standard.

I’ve always been intrigued by this question as it seems to have been whitewashed out of the history books. We just hear about the plucky and heroic female munitions workers, and they did do a magnificent job, but it’s as though they just arrived at the factory or wherever with the ability to make munitions etc. which is clearly nonsense.

I have an old photograph of a group of women factory workers one I believe to be my grandmother, but that’s as much as I know. I’m interested in finding out where it was and work they were doing. They are all in overall’s and looks like it was a dirty job, I’m thinking munitions.

She lived in Selston Nottinghamshire.

Any help on this enquiry, would be much appreciated.