Seventy-five years ago this week the Battle of the Ardennes began to draw to a close, with the Allies declaring victory. This was clearly an American victory, one that had come at the cost of more than 80,000 US troops killed, wounded and captured.

Ironically, although the Germans failed in their objective of punching a gap in the Allied front line to separate the American armies from their British allies, the British and Americans would become divided during the course of the Ardennes Offensive. Such would occur, not by force of German arms, but through a fake radio broadcast which, at a critical moment, helped to fuel an Allied public relations fiasco to a point where it went out of control.

Field-Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of British 21st Army Group, photographed with British Airborne Cap badge and wearing a British camouflage paratrooper jacket, 1945. Catalogue ref: INF2/44 (2652)

This inflicted lasting damage on Anglo-American relations during the final four months of the Allied campaign in North-West Europe. It all began with a dull and clumsily-worded press statement delivered by Field-Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, the commander of British 21st Army Group, who was placed in command of the northern segment of the Allied line throughout the German offensive.

Within the CAB 106 series are the working papers for the text of ‘Victory in the West, Volume II’. These were compiled for the second of an 18-volume official history of the Second World War, prepared by the Historical Section of the Cabinet Office and published by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office in 1968, which describes the 1944-1945 military campaign in Western Europe. The author, Major L F Ellis, dedicates a section of notes to the debacle that ensued from the Montgomery press conference, held on 7 January 1945, which took on the proportions of a crisis seemingly greater than the Ardennes Offensive itself. The notes read that Allied Supreme Commander, General Dwight D Eisenhower, later recalled this incident as one that caused him ‘more distress and worry than did any similar one of the war’ (CAB 106/1107).

At first glance, the text of the press statement appears relatively innocent, and seems to be nothing more than a typical briefing on the military situation since the German attack on 16 December 1944, with a glowing tribute to the resilience and fighting abilities of American soldiers in the battle. However, Montgomery had a far more pressing reason for holding this press conference. According to Ellis, certain factions of the British press, particularly the Daily Mail, had never given up hope of Montgomery being appointed overall commander of Allied Land Forces in Europe, making him second only to Eisenhower in terms of authority over Allied forces on the continent. The American military setback in the Ardennes gave the British press an opportunity to revive this argument; they critiqued American military chiefs and their handling of the German offensive, singling out Eisenhower for particular criticism.

Montgomery, while clearly defending Eisenhower as his superior, did not labour in his efforts to condemn the criticism of the British press outright. Indeed, his defence of Eisenhower appears disingenuous. In addition, while he went to great lengths to describe the valiant efforts of key American units in the battle, such as the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions, as well as the US 7th Armoured and 106th Infantry Divisions, he also underlined British involvement in the battle, such as that of the British 6th Airborne Division. Although, as Ellis observes, Montgomery delivered a ‘handsome tribute to the American army, its general tone and certain smugness of delivery undoubtedly gave deep offence to many American officers at SHAEF [Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force] and Twelfth Army Group’ (CAB 106/1107). However, the initial press reactions to the speech were favourable on both sides of the Atlantic, and it seemed that poorer impressions at an official level would die away, being remembered as little more than a small quarrel between British 21st Army Group and American 12th Army Group commanders.

At this point, Germany’s propaganda machine intervened.

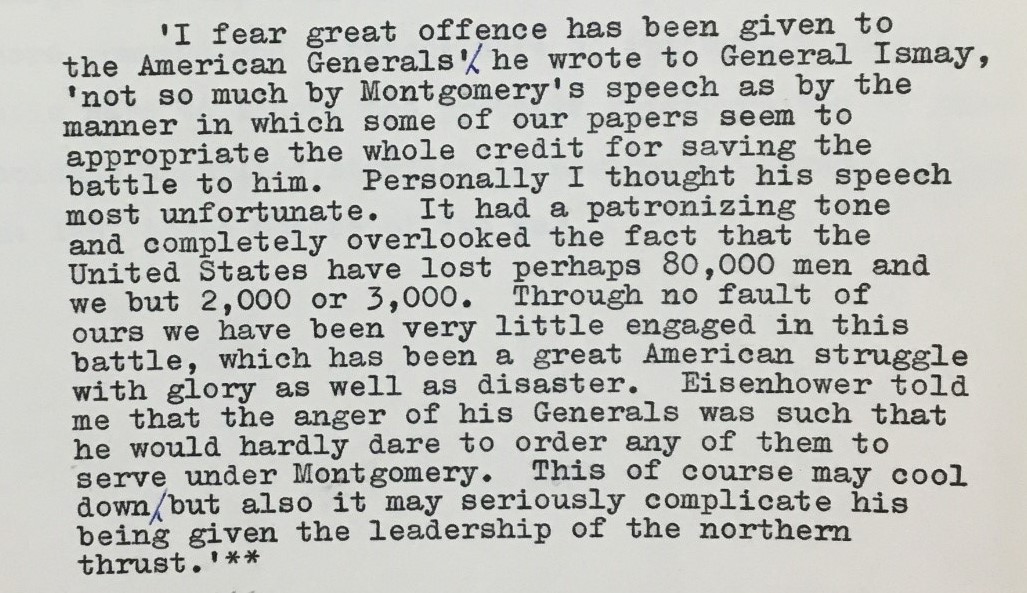

The above broadcast, recorded by the American Monitoring Service on the morning of 8 January, the day following Montgomery’s press conference, would be picked up on the same wavelength used by BBC to broadcast to Allied forces in Europe. It purported to be an official BBC comment on the press conference which, according to Ellis, ‘cleverly slanted the whole affair in a way calculated to give most offence to the Americans’ (CAB 106/1107).

This radio broadcast was heard by large numbers of American service personnel stationed in Europe, who were accustomed to listening to the BBC on the same wavelength, and who naturally assumed that the broadcast was genuine. Needless to say, American outrage at the implied slur on their military competence underlined the true destructive force of the fake radio broadcast.

Receiving wide publicity in the United States, the fake broadcast would be reproduced by all Hearst newspapers, with the New York Daily News running the story under the inflammatory headline ‘Applause to Monty: apple-sauce to Yanks’ (CAB 106/1107). The New York Herald Tribune produced a particularly icy paragraph from their correspondent who was reporting from the Ardennes front while embedded with General George Patton’s 3rd Army.

By far the most serious impact of the fake broadcast was the fact that senior officers at SHAEF and 12th Army Group, who accepted it as a genuine BBC bulletin, responded gruffly, with their responses to the Montgomery press conference being proportionately aggravated by the content of the bogus broadcast. This had the desired outcome of creating dissent within the Allied command structure at a moment when the Ardennes battle was turning in their favour. The British Minister of Information, Brendan Bracken, having promptly investigated the origin of the broadcast, was able to deny its authenticity on 10 January, with the British and American press carrying a BBC disclaimer and account of the incident on the following day. By then, the damage of broadcast had well and truly taken its toll.

General Omar Bradley, the commander of 12th Army Group, who was enraged by Montgomery’s lack of mention of the key American field commanders in the Allied counterattack during the Ardennes battle, issued his own statement to the press on 9 January. It was regarded as fair and moderate by most British and American papers, according to Ellis, and provoked little comment in any except one. The Daily Mail, resolutely sticking to an editorial policy which promoted Montgomery’s interests, decided to attack General Bradley’s statement as ‘A Slur on Monty’. Their key objections lay in the temporary and subordinate position to which Bradley had characterised Montgomery’s role in the Ardennes battle. While not wishing continue the ‘Transatlantic “slanging match”’ any further, the newspaper forcefully argued that Montgomery had been treated unjustly by the Americans, who had accepted the authenticity of the fake broadcast all too readily (CAB 106/1107).

This comment by the Daily Mail deepened the controversy which had been amplified by the fake broadcast, turning the fallout from Montgomery’s press conference into a full-blown public relations crisis, and the so-called ‘slanging match’ between the British and American press into a transatlantic media battle. By now, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was exasperated by the Anglo-American rift, and appalled at the dissent which had struck at the heart of the Allied command hierarchy in the midst of a major offensive campaign, felt it necessary to intervene. He confided in his military assistant, General Hastings Ismay, that Montgomery’s statement had been a disastrous blunder.

On 18 January, Churchill addressed the House of Commons for the first time in the year 1945 to brief members on the progress of the Allied counterattack in the Ardennes. With great care in his choice of words, he briefly alluded to the recent media controversy and clarified, for once and for all, who were the real victors of the Battle of the Ardennes.

‘I have seen it suggested that the terrific battle which has been proceeding since 16th December on the American front is an Anglo-American battle. In fact, however, the United States troops have done almost all the fighting and have suffered almost all the losses. They have suffered losses almost equal to those on both sides in the battle of Gettysburg. Only one British Army Corps has been engaged in this action. All the rest of the 30 or more divisions, which have been fighting continuously for the last month, are United States troops. The Americans have engaged 30 or 40 men for every one we have engaged, and they have lost 60 to 80 men for every one of ours. That is a point I wish to make. Care must be taken in telling our proud tale not to claim for the British Army an undue share of what is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever famous American victory’ (CAB 106/1107)[ref]Prime Minister’s speech to the House of Commons, 18 January 1945, Hansards, Vol. 407, Co. 416.[/ref].

In his summation of the affair, Major Ellis concluded that ‘Anglo-American relations during the war probably never went through a more difficult phase than in the first few weeks of 1945’, with the press on both sides of the Atlantic bearing major blame for accentuating the crisis beyond its actual proportions. Eisenhower later wrote that ‘no single incident that I have ever encountered throughout my experience as an Allied commander has been so difficult to combat as this particular outburst in the papers’ (CAB 106/1107).

Long after the war had ended, many American ex-servicemen continued to believe that the Nazi’s fake broadcast on 8 January 1945 had been a genuine BBC broadcast. The incident highlights a very important fact about what many regard as a modern-day phenomenon. While ‘fake news’ is nothing new, history teaches us that it can be powerfully destructive when wielded maliciously at a moment of crisis, leaving terrible and long lasting damage in its wake. The fact that during the post-war period, neither Eisenhower nor the gentle-souled Bradley ever truly forgave their British colleague for his bungled press statement, bears testament to this fact.

A very informative post as usual and another example of the logical wartime strategy to sow discontent between the Allied forces – greatly helped at the front-line level by the actions of individual soldiers and civilians they came into contact with and the much quoted impressions of US servicemen stationed in Britain.

Interesting to set this German example against the Allied efforts to focus on the similarities between the nations as seen in the sentiments of 1946 film ‘A Matter of Life or Death’.

Is there plans for a companion article focusing on the Allied efforts to split the elements of the Axis.

Excellent blog and very interesting. From the battle of Hastings to Nanking ,from the Boer war to the Falklands, fake news has always played its part it seems. Luckily nowadays we hopefully are more savvy to it. I agree with Richard above in seeing examples of Allied efforts to split the Axis

It’s amazing how some people are so quick to believe what is obviously fake news. Especially if it tends to reinforce their own perspective of events, or racial attitudes. It was well known that Germany used propaganda as a weapon, to spread false information to the German population. It is therefore very surprising that some of the allies fell for it!

Hello Richard

Thank you for your comment. This amazing piece of research only came to light two weeks ago while I was examining our collections pertaining to the Battle of the Ardennes. Many have heard of the disastrous press conference given by Montgomery, but few were aware of the factors that contributed to the public relations fiasco that ensued.

One has to thank Major L F Ellis, and the work of the Historical Section of the Cabinet Office, for bringing this to light over fifty years ago when they were compiling the series ‘Victory in the West’.

You raise an interesting point: there is a fascinating story to be told about ‘black propaganda’ during the Second World War and, yes, the Allies also made bogus broadcasts to Nazi Germany. In fact, in 2017, Marc Wortman, writing for Smithsonian Magazine, published this very interesting and quite hilarious article on the fake British radio show hosted Herr Gustav Siegfried Eins, also known as ‘der Chef’, which was broadcast at the behest of the British intelligence services: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fake-british-radio-show-helped-defeat-nazis-180962320/

I agree that it would be interesting to contrast this episode against similar episodes of black propaganda conducted by the Allies, and certainly I will follow up on your suggestion.

Amazing text – but please don’t write about NAZI from Outer Space or Northpole – just German ‘fake news’.

There is a wonderful book, “Bodyguard of Lies” which addresses the issue of “Fake News” promoted by the Allies. Alemain is one example of it’s earlier use. Patton and his “Command” were later uses prior to Normandy.

The title is from Churchill’s words at Yalta as he explained the need for such by the Russians. He said words to the effect that “in War, the truth must be surrounded by a bodyguard of lies,”

Very interesting info which I had not heard about before. Just shows that the nazis were skilled when it came to propaganda. Sad to see that this ‘fake news’ phenomena is still alive and kicking in modern politics.

Absolutely fascinating insight to the Battle of the Bulge just shows how damaging fake news can be

Hello Dr Quinn. Your post has clearly struck a note with readers of the blog.

From the small amount of posts I have read on the blog – small, simply because the blog has by its nature covers such a diversity of subjects – most posts attract a comment or two.

It appears obvious what one of your next posts will be about!

Indeed, it does Richard! I can assure you that, due to it’s evident popularity, I am following up with detailed research on “Black Propaganda”.

In fact, this topic will be investigated quite thoroughly so you can be assured of a blogpost or two in response to your request.

No, no, No! The story is more complex and convoluted than simply laying it at the feet of a natzi radio transmission. Montgomeries staff knew as it happened that it was a disaster. “Why didn’t you stop him?” one was asked.

Please read, “the press conference” (page 300) in Nojal Hamilton’s third volumn of his authorized biography, “Monty.” It’s been available since 1986. It shouldn’t be that hard.

This incident did not happen in isolation and occurred during a quite serious falling out over articles in The Economist critical of USA Policy towards the UK . A December 30th article in The New York Times (British Still Irked By US Critics; Weekly Calls For Ties To Russia) had the quote ‘some pieces published ostensibly to praise American Combat Troops have been so condescending tone that it might have been better if they had not been said’ which was exactly what they said about Montgomery and his Jan 7th conference comments. It appears the well had already been poisoned and the German rework of Monty was always going to be taken at face value because an American audience had been primed to hear it in that way.